The Fisher P-75 Eagle stands as one of World War II’s unique experimental aircraft, designed by the Fisher Body Division of General Motors (GM) to answer an urgent need for an American interceptor with exceptional climb rates and powerful performance. Though it ultimately never saw large-scale production, the P-75 Eagle exemplified the ambitious engineering efforts of the time, especially given GM’s commitment to the war effort. Its development journey, however, was marked by numerous design challenges and eventual cancellation as priorities shifted within the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF).

Origins of the P-75 Eagle

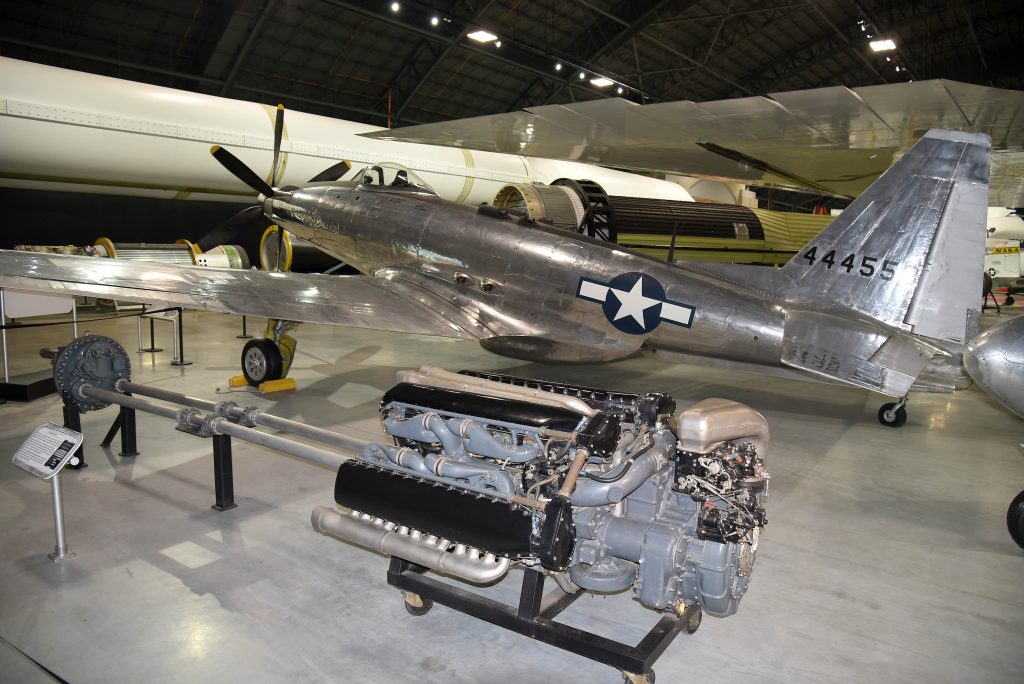

In 1942, the USAAF issued a request for a fast-climbing interceptor capable of outpacing existing models. Fisher Body, a GM subsidiary, answered this call with a proposal to develop a fighter using the Allison V-3420 engine, a powerful liquid-cooled, 24-cylinder powerhouse. By October 1942, GM signed a contract for two prototypes of the new aircraft, designated as the XP-75. Fisher Body’s approach to speed up production was innovative: it aimed to repurpose components from other existing aircraft. The initial design incorporated wing panels from the North American P-51 Mustang, the tail assembly of the Douglas A-24, and the landing gear from the Vought F4U Corsair. Although the outer wing panels were eventually sourced from the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk instead, this design philosophy was a novel attempt to accelerate the fighter’s production schedule.

Shifting Requirements and Expanded Orders

As the war progressed, the role of long-range escort fighters like the P-51 Mustang and the P-47 Thunderbolt became more critical to Allied air strategy than fast-climbing interceptors. Responding to this evolving need, the USAAF ordered six additional XP-75 prototypes adapted for long-range operations and placed a conditional order for 2,500 production units. The decision stipulated that if the first production model, the P-75A, didn’t meet requirements, the entire order could be canceled. While some sources suggest that GM’s involvement in the P-75 project may have been partly motivated by a desire to avoid mass production of Boeing B-29 Superfortresses, the P-75 Eagle received widespread media coverage. Dubbed the “wonder plane,” it was presented as a promising symbol of American engineering prowess, with high expectations leading up to its first flight.

The Testing Phase and Design Challenges

The XP-75 Eagle’s first test flight took place on November 17, 1943, powered by a formidable Allison V-3420-19 engine, generating 2,600 horsepower and driving contra-rotating propellers. By early 1944, six XP-75 prototypes joined the test program. However, this phase uncovered multiple technical challenges. Engineers struggled to stabilize the aircraft’s center of mass, and the V-3420 engine often failed to deliver its expected power output. Other issues included insufficient engine cooling, excessive aileron forces at high speeds, and poor spin recovery. Fisher Body responded by modifying the aircraft design, including adjustments to the tail assembly, the addition of a bubble canopy, and installation of a refined V-3420-23 engine, which successfully addressed many of the initial performance issues. The P-75A, with these improvements, began flight tests in September 1944.

Cancellation of the P-75 Program

Despite these improvements, the P-75A entered an environment where other aircraft, like the P-38 Lightning and P-51 Mustang, were already proving effective in long-range roles. By 1944, the USAAF was shifting focus, aiming to reduce the diversity of combat aircraft in production to streamline logistics and speed up deployment. With the end of the war potentially in sight, the P-75 program was ultimately deemed unnecessary, and on October 6, 1944, the USAAF canceled the Eagle’s production. In total, eight XP-75 prototypes and six P-75A production models were built. While the Eagle never achieved operational status, it remains a noteworthy example of wartime engineering ingenuity, and the rapid design adaptation made possible through component sharing from different aircraft.

Legacy and Preservation

The sole remaining P-75A Eagle, serial number 44-44553, resides at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. After extensive wear was discovered in the airframe in 1999, the museum undertook a full restoration, and the aircraft returned to display in the museum’s Experimental Aircraft Gallery. Today, the Fisher P-75 Eagle serves as a testament to the era’s bold aviation experiments and the dynamic shifts in military priorities during World War II. While the P-75 program was ultimately a dead-end project, its development underscores the experimental approaches and adaptive engineering that were hallmarks of World War II’s aviation landscape.

Throughout aviation history, countless aircraft designs have sparked the imagination of engineers, pilots, and aviation enthusiasts. Many of these innovative concepts, however, never made it past the drawing board or prototype stage. “Grounded Dreams: The Story of Canceled Aircraft” delves into the fascinating world of these ambitious projects that, for various reasons, were never fully realized. From groundbreaking technological advancements to strategic missteps, this exploration uncovers the stories behind the aircraft that promised to revolutionize the skies but were ultimately grounded before they could take flight. Join us as we journey through the highs and lows of aviation history, spotlighting the aircraft that could have changed the course of aeronautical progress had their dreams not been deferred. Check our previous entries HERE.

Related Articles

"Haritima Maurya, pen name, ""Another Stardust,"" has been passionate about writing since her school days and later began sharing her work online in 2019. She was drawn to writing because of her love for reading, being starstruck by the art of expression and how someone can make you see and feel things exclusive to their experience. She wanted to be able to do that herself and share her mind with world cause she believes while we co exist in this beautiful world least we can do is share our little worlds within.

As a commercial pilot, Haritima balances her passion for aviation with her love for storytelling. She believes that, much like flying, writing offers a perspective beyond the ordinary, offering a bridge between individual experiences and collective understanding.

Through her work, ""Another Stardust"" aims to capture the nuances of life, giving voice to moments that resonate universally. "

Be the first to comment

Graphic Design, Branding and Aviation Art