As World War II came to an end, aviation was advancing at an evolutionary rate. Both aircraft and helicopters were undergoing modern changes and were becoming more practical day by day. However, there was still a gap in urban travel since airplanes needed long runways, and helicopters, while versatile, were slow and limited in range. Thus, the idea of combining the best features of both was born. The search for an aircraft that could take off and land anywhere like a helicopter, but could fly fast and far like a airplane was undertaken. The Fairey Rotodyne was a British Hybrid Aircraft designed in the 1950s as a solution to this very problem. This was the dream, a dream designed to be the perfect “flying bus” for short city-to-city routes landing on rooftop helipads or compact airstrips. This idea was not only exciting for commercial aviation, but it also caught the attention of the military. They saw potential in the Rotodyne to transport troops and supplies quickly without needing runways in war zones.

Designing the Dream

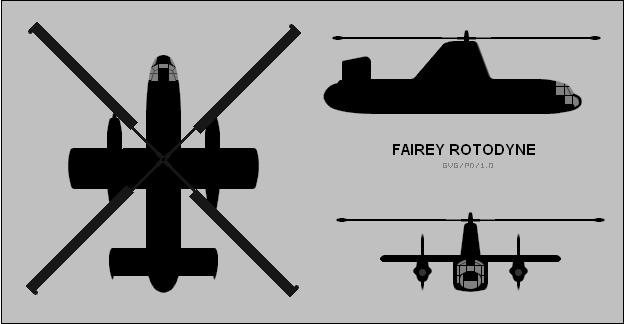

This led to a series of experimental designs, with The Fairey Aviation Company in the UK taking the lead. They were already experts with their contribution to World War I with aircraft like Fairey Swordfish, but Rotodyne was their most ambitious project yet. The project was led by one of their top engineers, Dr. J.A.J. Bennett, who focused on incorporating a rotor-driven lift system with conventional wings and engines for forward thrust. However, the rotor blades were not powered during flight; instead, they were auto-rotating. This design reduced drag and increased efficiency during forward flight. During takeoff and landing, the rotor was powered by compressed air jets at the tips of the blades. But once the aircraft was in the air and flying forward, the rotor switched to “autorotation” mode. This meant that the rotor was not powered but just spinning freely, much like a helicopter in a glide. It featured two Napier Eland turboprop engines that powered both the aircraft’s forward flight and the rotor during takeoff and landing. The smooth transition from vertical to forward flight was no easy task, but they made it work.

The Prototype

The Fairey Rotodyne prototype XR942 made its first flight on November 6, 1957, with squadron Leader Ron Gellatly, an experienced test pilot. It took off from White Waltham Airfield in Berkshire, UK and was a success. The Rotodyne took off vertically, switched to forward flight smoothly, and landed again without any issue. This successful first flight generated buzz in the aviation world. Both commercial airlines and military organizations started paying attention to what the Rotodyne could offer.

Setting Records, Making History

The Rotodyne was different from anything else in the sky at that time. Its main advantage was versatility; it could land almost anywhere. For businesses or governments that needed fast transportation between cities or remote locations, this was a game changer. The auto-rotate design of the rotor allowed Rotodyne to reach speeds of around 190 knots (about 220 mph), thus making it much faster than helicopters at the time. The aircraft also offered a range of over 700 miles (1,100 km) which made it highly suitable for short to medium-haul routes. Additionally, Rotodyne could carry a lot more passengers than a traditional helicopter, transporting around 40 passengers comfortably, making it large enough for commercial use. With its unique features and successful test flights, it attracted many potential customers including British European Airways. BEA expressed interest in ordering Rotodynes for domestic routes, while military officials were particularly intrigued by its ability to land in remote areas. This made it ideal for transporting troops or equipment in places where there were no runways.

The End of the Line

Despite all the promise, the Rotodyne project came to an abrupt halt in 1962. Several factors contributed to its downfall. One of the most significant issues was noise; the air jets used to power the rotor during takeoff and landing were incredibly loud—too loud for urban areas. Since the whole point of the Rotodyne was to operate between city centers, the noise problem became a dealbreaker for many potential buyers. Financial issues were another major problem; Fairey Aviation needed help to get the funding required to move the Rotodyne into full production. They needed government backing to keep going, but the British government eventually withdrew its support, leading to bankruptcy. Combined with the noise issues and rising competition from other aircraft manufacturers focusing on jets, the Rotodyne’s future started to look bleak.

Dream that Inspires

The only prototype, XR942, was scrapped after the cancellation of the project in the early 1960s. The Rotodyne was never mass-produced, and the dream of city-to-city flights without the need for airports faded away. However, the concept of vertical takeoff and landing aircraft continues to inspire engineers today. With advancements in electric propulsion and quieter rotors, many modern eVTOL (electric vertical takeoff and landing) aircraft owe a lot to the groundwork laid by the Rotodyne. Companies today are still chasing that dream of quick, efficient, and flexible air travel—just like the Rotodyne promised over 60 years ago.

Throughout aviation history, countless aircraft designs have sparked the imagination of engineers, pilots, and aviation enthusiasts. Many of these innovative concepts, however, never made it past the drawing board or prototype stage. “Grounded Dreams: The Story of Canceled Aircraft” delves into the fascinating world of these ambitious projects that, for various reasons, were never fully realized. From groundbreaking technological advancements to strategic missteps, this exploration uncovers the stories behind the aircraft that promised to revolutionize the skies but were ultimately grounded before they could take flight. Join us as we journey through the highs and lows of aviation history, spotlighting the aircraft that could have changed the course of aeronautical progress had their dreams not been deferred. Check our previous entries HERE.

Related Articles

"Haritima Maurya, pen name, ""Another Stardust,"" has been passionate about writing since her school days and later began sharing her work online in 2019. She was drawn to writing because of her love for reading, being starstruck by the art of expression and how someone can make you see and feel things exclusive to their experience. She wanted to be able to do that herself and share her mind with world cause she believes while we co exist in this beautiful world least we can do is share our little worlds within.

As a commercial pilot, Haritima balances her passion for aviation with her love for storytelling. She believes that, much like flying, writing offers a perspective beyond the ordinary, offering a bridge between individual experiences and collective understanding.

Through her work, ""Another Stardust"" aims to capture the nuances of life, giving voice to moments that resonate universally. "

It’s quite fascinating that humans are capable of anything, paper sketch to actual flight. Hoping that community will one day invest in these innovations. Ideas never die !

Kudos to the author for extraordinary writing!

Decades ago, a large crate was located in Building 606, a ramshackle and rough structure dating to WW2 constructed with some felled trees and tarpaper. The Bradleu (later New Emgland) Air Museum was using this building for rudimentary storage. Inside was a large factory model of the Rotodyne. This crate had been donate by Kaman Aircraft Corporation. Kaman had supposedly been chosen as the US-based manufacturer of Rotodynes under license, which, we all know, never came to fruition. I wonder where the model is now. At the time, The museun had the world’s largest collection of Kaman aircraft in its collection. I worked on a couple of them.