By Courtney Hale Caillouet

Spartan Aircraft is far more notable for its Model 7 Executive aircraft, but the company’s rather humble beginnings were with a biplane. The C3 model was based on a design by Willis C. Brown in the late 1920s. It was a rear cockpit design, with two passengers placed side-by-side in the front compartment, and the fuselage being of welded tubular steel with solid spruces/I-beam spars and wood ribs. The powerplant was a challenging aspect for the first production model, changing several times but ultimately ending with the Wright Whirlwind J-6 series of radial engines. These became the standard for further production models, designating it as the C3-5. This was later changed to C3-165, designating that it utilized the five-cylinder version and produced 165 hp. Roughly 40 aircraft of this subtype were manufactured.

When college student, Connor Flynn, was offered a project by an older gentleman named Bruce Roberts he was intrigued. Inside of a wasp-infested shed, laid a tubular steel frame that was once graced the skies. It was a Spartan C3-165, built at their Tulsa factory in September of 1929. The registration number was NC61N and carried serial #133, still stamped into the steel in several different locations. With nothing more than a frame, a tail wheel fork, and some elevator trim components, this didn’t appear to be a suitable project. This was until Bruce revealed that he also had stacks and stacks of original drawings for the aircraft, all of which had been rescued from the factory’s dumpster. Now Connor’s intrigue turned into true excitement. With the frame and drawing, there was some serious potential to rebuild a very rare biplane.

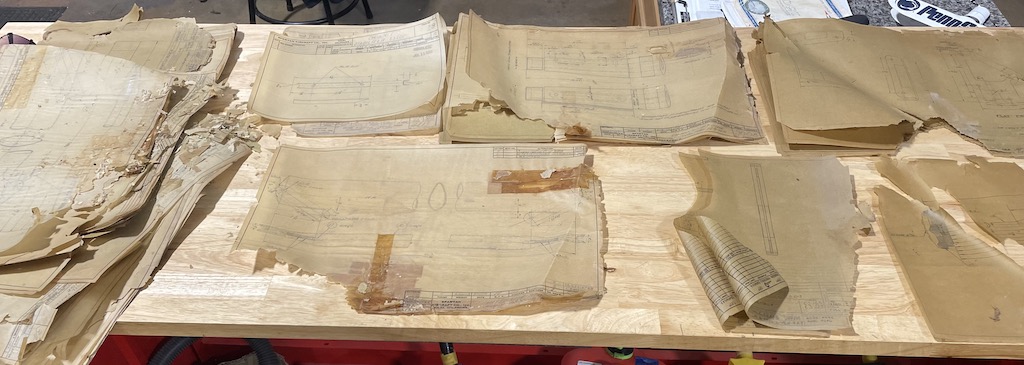

A majority of Connor’s time is spent attending Pennsylvania College of Technology, working towards a Bachelor’s in aviation maintenance. As a side job, he has been working on some other restoration projects at New Garden Airport – a Fleet 7B and a Fairchild 24. This is where he met Bruce, who is a retired aircraft mechanic. Bruce, a collector of many things aircraft-related, acquired the Spartan in 1971. Not all the prints were stored together in Bruce’s attic, so he comes to the airport from time to time, bringing Connor another stack as he finds them. They are largely intact, but the decades have made them very fragile. He has tried to scan them digitally as soon as he receives a new set, working to preserve this valuable information. He also discovered that the smaller, 8.5 x 11 drawings actually fit nicely in restaurant menu holders, allowing them protection while also being usefully displayed. The larger prints have required custom-built folders. With about three or four hundred drawings at present, this is a huge task just in itself. His small dorm room has become an archiving center, constantly thumbing through the stacks, checking that the prints have been scanned and properly categorized, hoping that they can be stored before they completely flake apart in his hands. He also has a full drawing list, which has allowed him to begin matching up what he has, versus what he’s missing. Right now, most are for parts – a floorboard cup, passengers’ entry step, rear brake pedal casting, and a random wood rib for here or there…But the large drawings are still missing. For instance, he has all the drawings for the wing center section and all the mounting brackets for the wings themselves, but no prints for the actual wing structures. He describes this as having a picture of the puzzle, but without any of the pieces. And with only two complete -165s in existence, this makes the build even more challenging. Connor has been granted permission to examine, photograph, and measure Spartan NC285M at Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome, so he has plans to make the trip that way this coming summer, hoping to get a better look at some of these missing pieces.

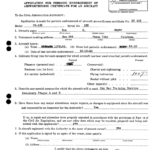

When agreeing to take on this project in 2022, Connor didn’t even know what a Spartan C3 was, which sent him down a bit of a rabbit hole. He contacted the FAA, requesting all the records for NC61N. In less than two weeks, he had scans of all previous airworthiness certificates and registrations dating back to the airplane’s first owner – Skelly Oil. Interestingly, Spartan was originally named Mid-Continent Aircraft Co., which earned attention from William G. Skelly, who was looking to invest in the aviation boom. (In fact, Connor has some earlier drawings that still say Mid-Continent.)

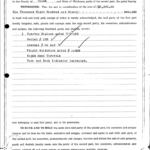

With Skelly coming on board, the name changed to Spartan Aircraft Company, with Willis Brown as president. Skelly Oil purchased aircraft #113, which painted it with a company livery and put nearly 600 hours on the airframe. From there, it was bought and sold several times, going to Ohio, Indiana, Texas, and then eventually back to Oklahoma in 1942. There, it was owned by flight instructor, Tom Smyer of Ponca City, who listed his address as “Airport.” He stated in the airworthiness application that the Spartan’s purpose would be for “CAA war training service secondary stages A and B”. Perhaps this airplane was used to train some of America’s WWII pilots but unfortunately, no other history is available at this time. In 1945, it was sold and extensively modified to become an agricultural sprayer, which is a very hard life for a wood and fabric aircraft. Francis Rourke operated Southwest Agricultural Flying Enterprises. There is even a handwritten letter to the CAA, requesting a replacement registration, as the original “was blown out of the ship”. It was last registered as airworthy in 1948, with the CAA making an inquiry into its status in 1955. At that time Rourke stated that Southwest still owned the airplane “and is in the process of rebuilding”. By 1958 it was sold to Roger White who wrote to the CAA that same year, declaring the aircraft was destroyed and requesting to use 61N for his homebuilt Cougar aircraft. He held onto the remnants of the Spartan until Bruce took possession of it in the early ’70s, eventually getting his hands on the drawings from the gentleman who rescued them.

Being a full-time student, this project is a huge endeavor for a 20-year-old. Connor says he can complete it, one part at a time, without impacting his wallet too heavily. When time allows, he goes into the small corner of the T-hangar space that his boss gave him, he pulls out a component drawing and begins to build. Cutting wood, bending sheet metal, sanding, and welding – working on just one of the many puzzle pieces. He even created a Facebook page to share his progress, hoping to reach out to others who have an interest in his C3 project. He plans to build #133 as close to the original as possible, even someday acquiring a Wright J-3-5 to hang up front. He knows this project will be lengthy but feels time is on his side, being so young. With his education and the experience he is gaining in his job, he looks forward to his future with this rare airplane, believing it will be airborne once again.

You can follow Connor’s progress with the Spartan on Facebook.

[wbn_ads_google_three]

Related Articles

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.

![Young Man, Old Plane – BIG Challenge 9 Connor Flynn sits in the bare fuselage of Spartan C3-165 s/n113, the aircraft he's restoring to airworthiness. [Photo via Connor Flynn]](https://vintageaviationnews.com/wp-content/uploads/Spartan-C3-165-Biplane_6413-Edit.jpg)

![CAF Airbase Georgia Reaches Milestone In Stearman Restoration 12 The Stearman for the first time sees the light of the CAF Airbase Georgia's hangar. You can see the tail of the unit's SBD-5 Dauntless. [Photo by Angela Decker]](https://vintageaviationnews.com/wp-content/uploads/CAF-Airbase-Georgia-Stearman-Restoration-150x150.jpg)

![Just Over Two Weeks to Go Until Warbirds Over Wanaka 2024 19 Another crowd favourite, the Grumman TBM-3E Avenger "Plonky", getting near the end of some major engineering work in time for Wanaka. [Photo via Warbirds Over Wanaka]](https://vintageaviationnews.com/wp-content/uploads/20240307-Avenger-via-Warbirds-Over-Wanaka-150x150.jpg)