On this day in aviation history, December 22, 1964, the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird made its first flight. A favorite of many aviation enthusiasts, the Blackbird remains the fastest and highest-flying jet-powered aircraft in history, even 60 years after its maiden flight.

The SR-71 was developed from the Lockheed A-12, a high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft developed at Lockheed’s Skunk Works Division that was flown by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to conduct reconnaissance on Soviet military installations while flying at Mach 3 and altitudes up to 85,000 ft to avoid interception. The US Air Force sought a new variant of the A-12, with Lockheed initially designating this proposal as the R-12. This new development was to have larger fuel tanks for greater range, and while the A-12 had a single pilot, the new aircraft was to have both a pilot and a reconnaissance systems officer (RSO), who would operate the monitoring and defensive systems, which included an Electronic Counter Measures (ECM) system that could jam most acquisition and targeting radar. Because it was being developed at the same time as the proposed reconnaissance-strike variant of the North American XB-70 Valkyrie (the RS-70), the aircraft Lockheed called the R-12 was to be initially designated as the RS-71.

Unlike the A-12, the RS-71’s existence was revealed before its first flight. As Democratic President Lyndon Johnson sought to be elected on his own merits in the 1964 election, his Republican challenger Senator Barry Goldwater accused the Johnson administration of falling behind the Soviet Union’s military at the height of the Cold War. President Johnson sought to invalid the senator’s argument by disclosing the existence of the YF-12, an interceptor variant of the A-12 to provide cover for the A-12 program. He also chose to reveal the existence of the RS-71, but in the announcement, it was revealed as the SR-71. Reportedly, the Air Force Chief of Staff, General Curtis LeMay, had behind the scenes preferred to call the RS-71 the SR-71 in order for its designation to stand for “strategic reconnaissance”. Whether through LeMay’s influence or as an act of saving face in the wake of Johnson’s press release, the aircraft was now officially called the Lockheed SR-71.

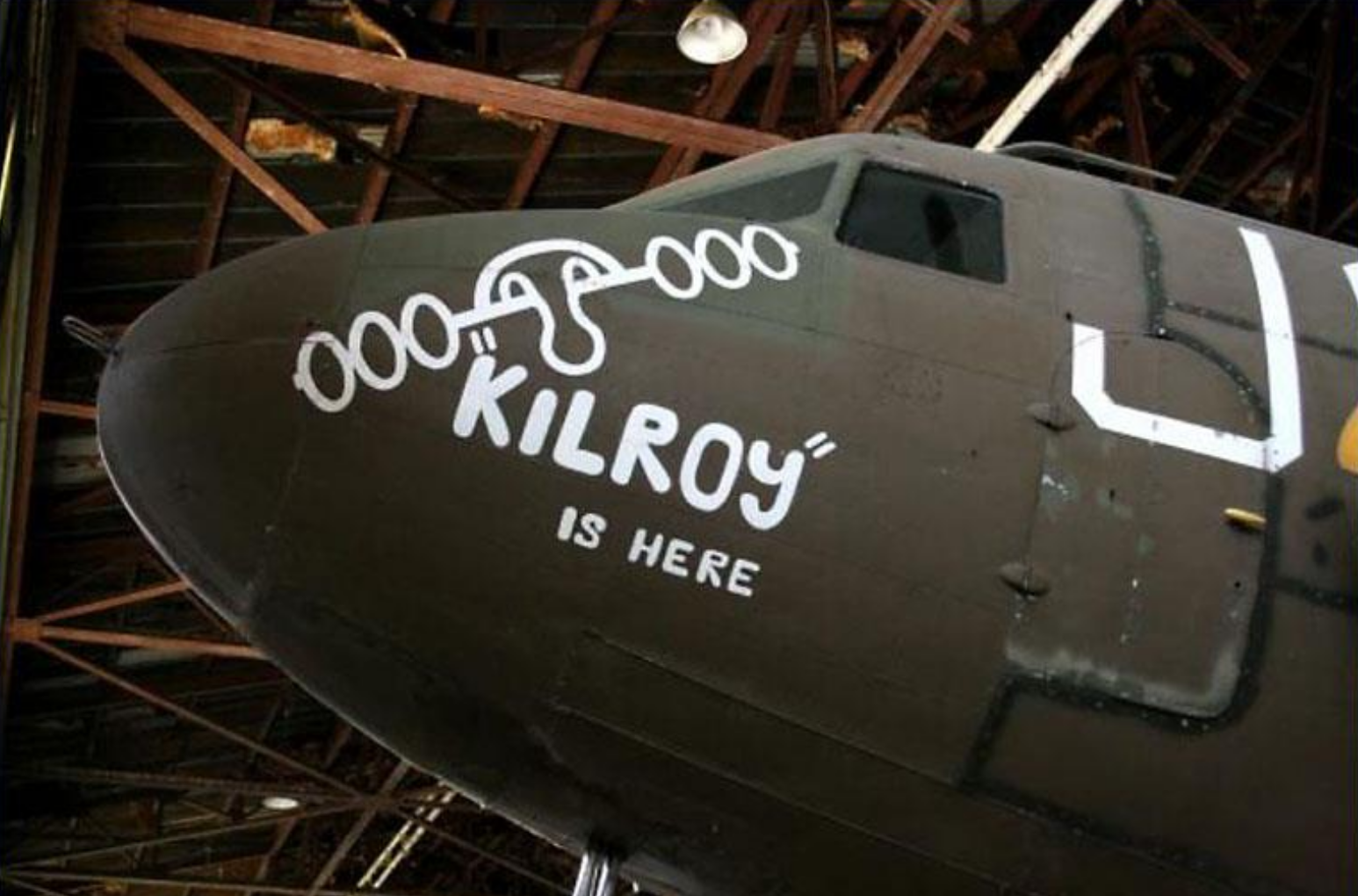

On December 22, 1964, test pilot Bob Gilliland took the first SR-71A, 61-7950, on its first flight at USAF Plant 42 in Palmdale, California. Gilliand took 61-7950 up to 45,000 feet (13,716 meters) in altitude and when supersonic on the type’s first flight before landing 22 miles to the northeast of Palmdale at Edwards Air Force Base. In 1966, the first SR-71s in USAF operational service were assigned to the 4200th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing (later redesignated as the 9th SRW) at Beale AFB, California. Due to the black paint, the SR-71 earned the nickname Blackbird, and when the 9th SRW was sent to Kadena Air Base in Okinawa, the locals referred to the SR-71 as the Habu, after an indigenous pit viper. The SR-71 crews soon adopted this nickname as well, and during the Vietnam War, SR-71s and A-12s, which were retired in 1968, conducted reconnaissance on North Vietnam and North Korea as well as the Pacific shoreline of the Soviet Union. In all, 32 SR-71 Blackbirds were built. The majority of these were SR-71A models used for reconnaissance missions, while two SR-71B trainers were built, and a single SR-71C, which combined the wing and rear section of YF-12A 60-6934 (which had been written off by a fire following a landing mishap) with the forward fuselage from a static test airframe.

On several occasions, North Vietnamese and North Korean surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) were fired at SR-71s. However, although the missiles could reach similar speeds as the Blackbirds themselves, the SR-71 crews were able to detect the incoming missiles before they were at altitude to hit them, and often times the Blackbird’s best defense was to open the throttles and accelerate away from the missiles. Even the Soviet’s Mach 3 interceptor, the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 “Foxbat” was unable to catch the Blackbird.

Besides flying out of Kadena AB, Beale AFB, and Palmdale, some SR-71s were later operated out of RAF Mildenhall, England to conduct reconnaissance on the Soviet Navy’s Northern Fleet and the Baltic Fleet. The latter route became known as the “Baltic Express” and had to operate within a small pocket of international airspace above the Baltic Sea, monitored by both the Soviets and the Swedish, who, while neutral, sent up SAAB J37 Viggen fighters to intercept SR-71s if they violated Swedish airspace. On June 29, 1987, SR-71A 61-7964 was flying a reconnaissance mission over the Baltic when its right engine exploded, causing it to lose altitude and enter Swedish airspace. A pair of unarmed Viggens on a training mission were sent to the Blackbird’s location, but upon realizing its was in obvious distress, the Swedish interceptors escorted the Blackbird, with an armed pair relieving the first pair and staying with the Blackbird until it reached Danish airspace, preventing the Soviet interceptors from getting a clean lock on the Blackbird, which managed to return to base. After 30 years of classification, the details of the historic event were made public, and the four Swedish pilots were awarded the US Air Force’s Air Medal in 2018.

While the Blackbird was certainly a rewarding aircraft to fly in that it offered its pilots an unforgettable experience and a unique vantage of the Earth from 80,000+ feet, it was a challenging aircraft to fly and maintain. Of the total of 32 Blackbirds built, 12 were lost in accidents between 1966 and 1989, with 11 of these being lost between 1966 and 1972. The aircraft also required a special type of fuel, JP-7, and often had to be refueled in midair, as it would only be partially loaded with fuel to reduce stress on the wheels and brakes on takeoff. During the refueling process, the Blackbird was refueled by a Boeing KC-135Q Stratotanker, which was specially modified to deliver JP-7 fuel.

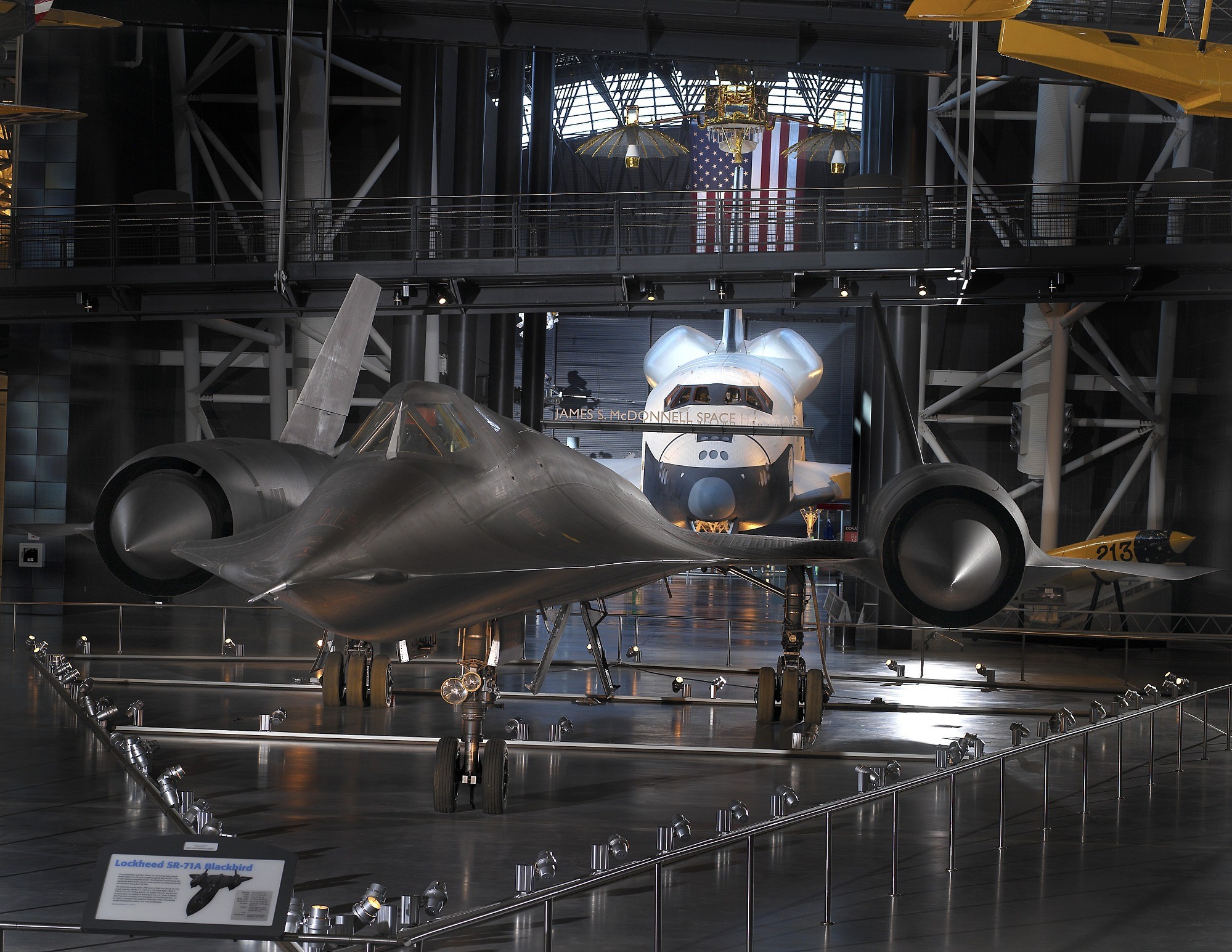

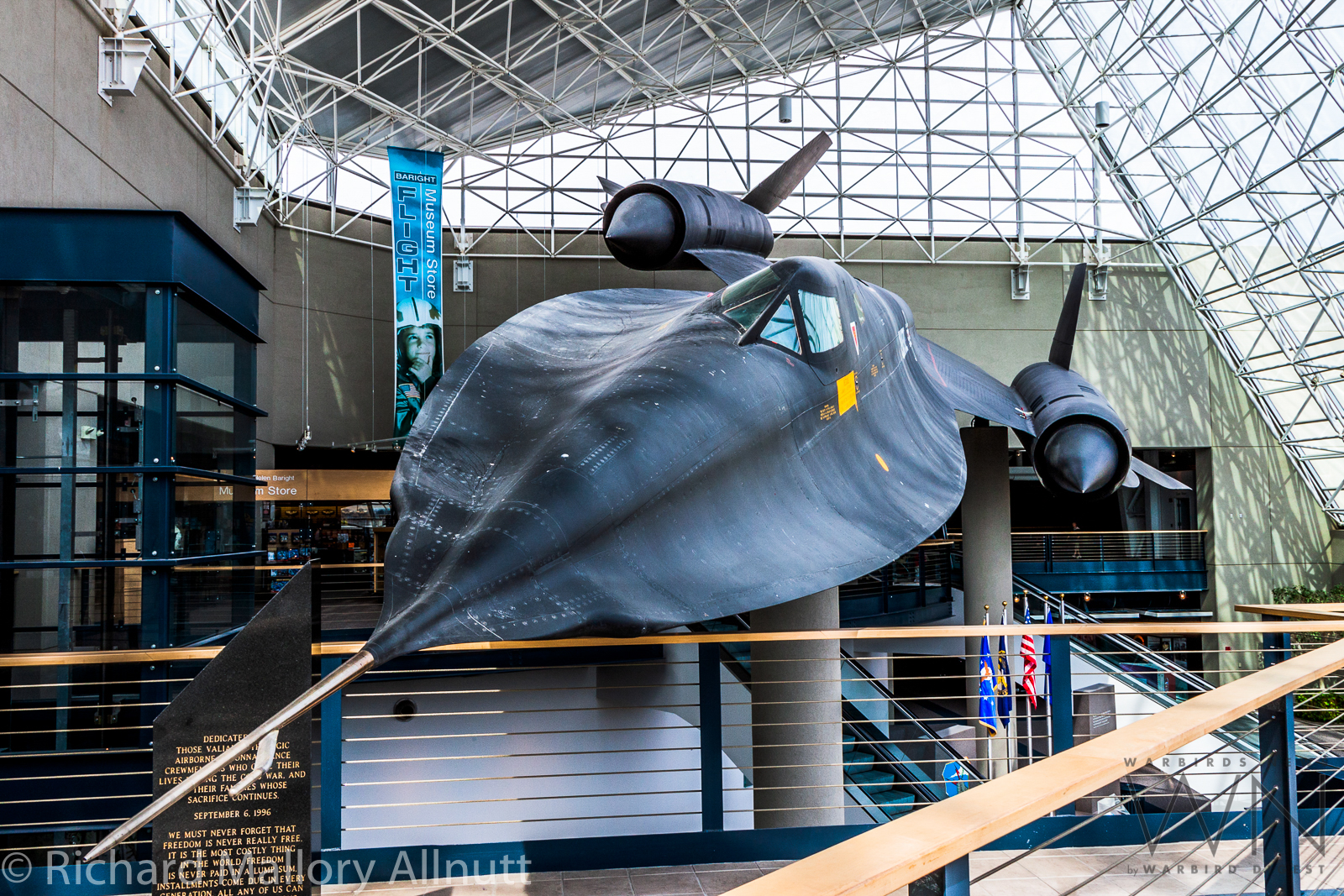

By the 1980s, funding for maintaining the SR-71 had to compete with various other military programs, such as surveillance satellites and proposals for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) that offered additional means of strategic reconnaissance. Another factor to consider was the fact that unlike its predecessor, the Lockheed U-2, the SR-71 was not equipped with a data link to transmit the intelligence it gathered in real time, so analysts had to wait for the Blackbird to land in order to gain the information it had obtained. On November 22, 1989, the USAF terminated the SR-71 program, but in 1995, a small number of Blackbirds were briefly reactivated at Beale AFB, equipped with a near-real time data link, but the Blackbird, capable of outrunning missiles, was not capable of outrunning congressional discretionary spending, and in 1998, the Air Force formally retired the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird, while two aircraft flown by NASA for research flights would remain active for only another year before themselves retiring in 1999. Today, all surviving SR-71s and the preceding A-12s are preserved in museums across the United States, though one Blackbird was sent to join the American Air Museum in Britain at the Imperial War Museum Duxford complex near Cambridgeshire, England. In the case of Blackbird 61-7972, which was selected for preservation at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, it set four new speed records flying from Plant 42, Palmdale, California to Washington Dulles International Airport, Virginia, flying between Los Angeles and Washington, D.C. at an elapsed time of 64 minutes 20 seconds, covering 2,299.7 miles (3,701.0 km) at an average speed of 2,144.8 miles per hour (3,451.7 km/h). It now rests at the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center at Dulles Airport.

Even today, standing silently in a museum gallery, the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird evokes a sense of speed and high-performance. It’s unique shape, all-black paint, and service record makes it a favorite of all kinds of enthusiasts, from those who were born well after its final flight, to those who saw it streak across the sky, or even a select few who know what it was like to see the curvature of the earth from 80,000 feet at Mach 3.3 through the helmet visor of a high altitude flight suit. The fact that even 60 years after its first flight, it remains the world’s fastest highest-flying jet aircraft has secured its place firmly in the annals of aviation history.

Today in Aviation History is a series highlighting the achievements, innovations, and milestones that have shaped the skies. All the previous anniversaries are available HERE