On October 11, 1968, NASA redefined the phrase “nothing is impossible” as they sent the first crewed fight to space. The Apollo 7 was the Apollo Program’s first successful spacecraft, with its crew of Commander Walter M. Schirra, Command Module Pilot Donn F.Eisele, and R. Walter Cunningham. Each of these astronauts brought their invaluable share of expertise on board, with Schirra carrying his priceless experience from Project Mercury and Gemini. The crew successfully completed the mission objectives, showcasing human resilience in extreme space conditions. The mission was crucial in testing the spacecraft systems, especially the Command and Service Module (CSM) needed for future lunar missions and the lunar module (LM). Furthermore, the success of Apollo 7 gave NASA the confidence to proceed with Apollo 8 and later Apollo 11 in 1969. Apollo 7 laid the groundwork for a journey of orbiting the Moon and then, one day, landing on it.

Crafting the Craft

Crew Preparation

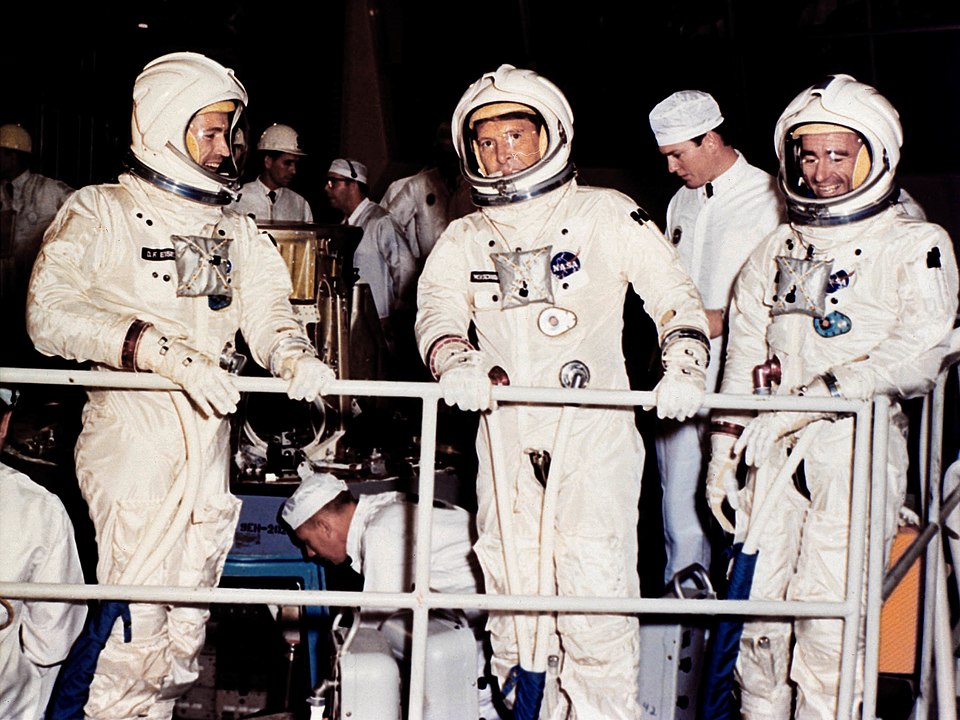

After the unfortunate incident of the Apollo 1 fire, the Apollo 7 crew lacked confidence in the staff at the California plant that built the Apollo command modules (CSM), and hence, they were determined to be involved in every step of the construction and testing of the spacecraft. The crew underwent five hours of extensive training for every one hour expected during their 11-day mission duration. The training also involved technical briefings, self-study, and pilot meetings, as well as launch pad evacuation drills and water egress training as a safety exit measure during splashdown. Another safety procedure was practicing the firefighting equipment, especially due to the Apollo 1 fire incident. The crew also trained on the Apollo Guidance Computer at MIT to familiarize themselves with the spacecraft’s critical navigation and control systems. These systems involved each astronaut spending 160 hours in simulations of the command module. The simulations included a “plugs out” test with the prime crew aboard, but with an open hatch to avoid a repeat of the Apollo 1 tragedy. Another precaution taken in light of Apollo 1 was an outward-opening hatch in Apollo 7, unlike the previous design, which had an inward opening. This design was the reason the crew could not escape during the Apollo 1 fire.

The Apollo 7 spacecraft included a Command and Service Module 101 (CSM-101), the first Block II CSM to be flown with the capability of docking with a Lunar Module (designed to carry astronauts from lunar orbit down to the Moon’s surface and back). The spacecraft also featured a launch escape system for abort scenarios and a Spacecraft-Lunar Module Adapter (SLA). However, the SLA did not house a Lunar Module for this mission either. Since Apollo 7 flew only in low Earth orbit and lacked a Lunar Module, it was launched with a Saturn IB booster. It was the fifth Saturn IB launched, though the first to carry a crew into space.

Launching the Vision

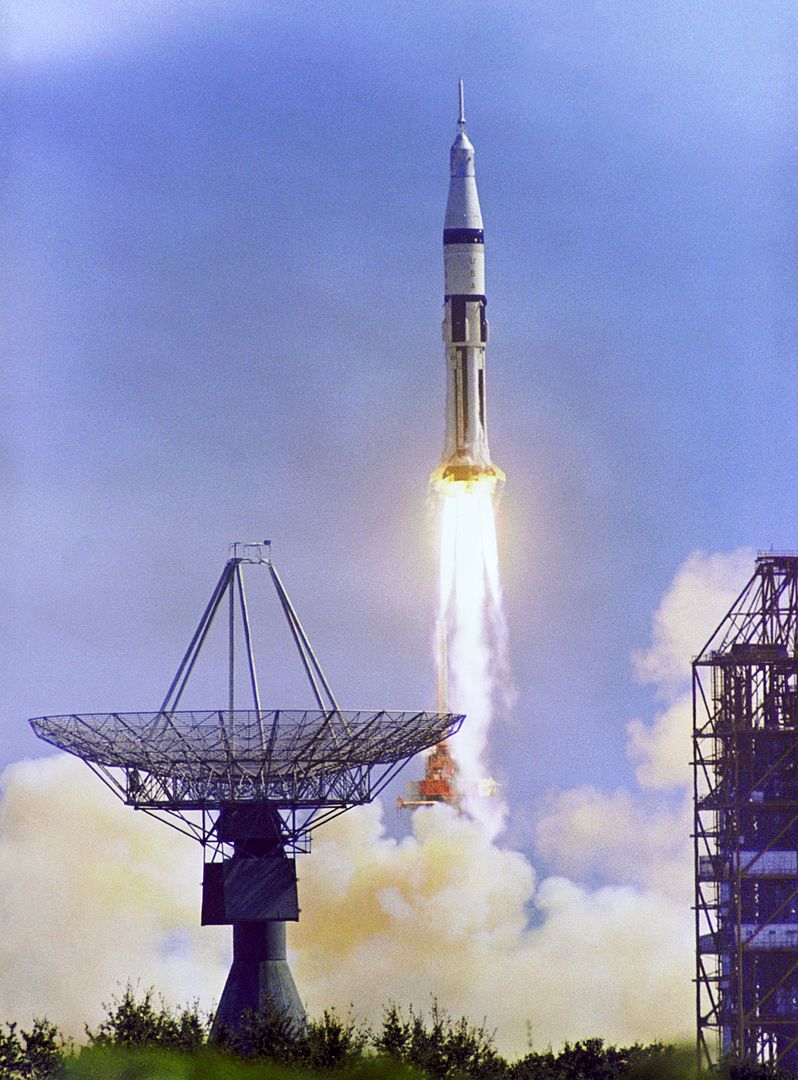

First Stage – Apollo 7 launched from Launch Complex 34 at 11:02:45 am EDT on Friday, October 11, 1968, nearly 22 months since Apollo 1. It was the only crewed mission to launch from Launch Complex 34 at Cape Kennedy Air Force Station, making a little history of its own. However, the iconic moment was not as smooth sailing as it might have appeared. The wind was blowing from the east, violating safety rules. In case of an abort, the Command Module could be blown back over land instead of landing in the water. Despite this risk, and Apollo 7 still being equipped with the older Apollo 1-style crew couches, mission managers waived the safety rule, and Commander Wally Schirra reluctantly agreed to proceed with the launch.

Second Stage – The liftoff proceeded smoothly, with no significant anomalies during the boost phase. The Saturn IB rocket performed exceptionally well on its first crewed launch. The astronauts described the ascent as smooth, marking a successful launch. This launch gave Commander Schirra a record of his own as he became the oldest person to enter space at that time and also the only astronaut to fly in all three programs: Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo. (Mercury was NASA’s first human spaceflight program, and the Gemini program extended NASA’s capabilities by carrying two astronauts per mission. It was designed to test spaceflight techniques like spacewalking, docking, and longer-duration flights.)

Third Stage – Within the first three hours of flight, the crew performed two critical actions simulating maneuvers required for lunar missions. They maneuvered the spacecraft while still attached to the S-IVB stage, mimicking the burn that would send lunar missions to the Moon. After separation from the S-IVB, Schirra turned the Command and Service Module (CSM) around and approached a docking target painted on the S-IVB, simulating the docking procedure with the Lunar Module (LM) for future Moon-bound missions.

Apollo Returns

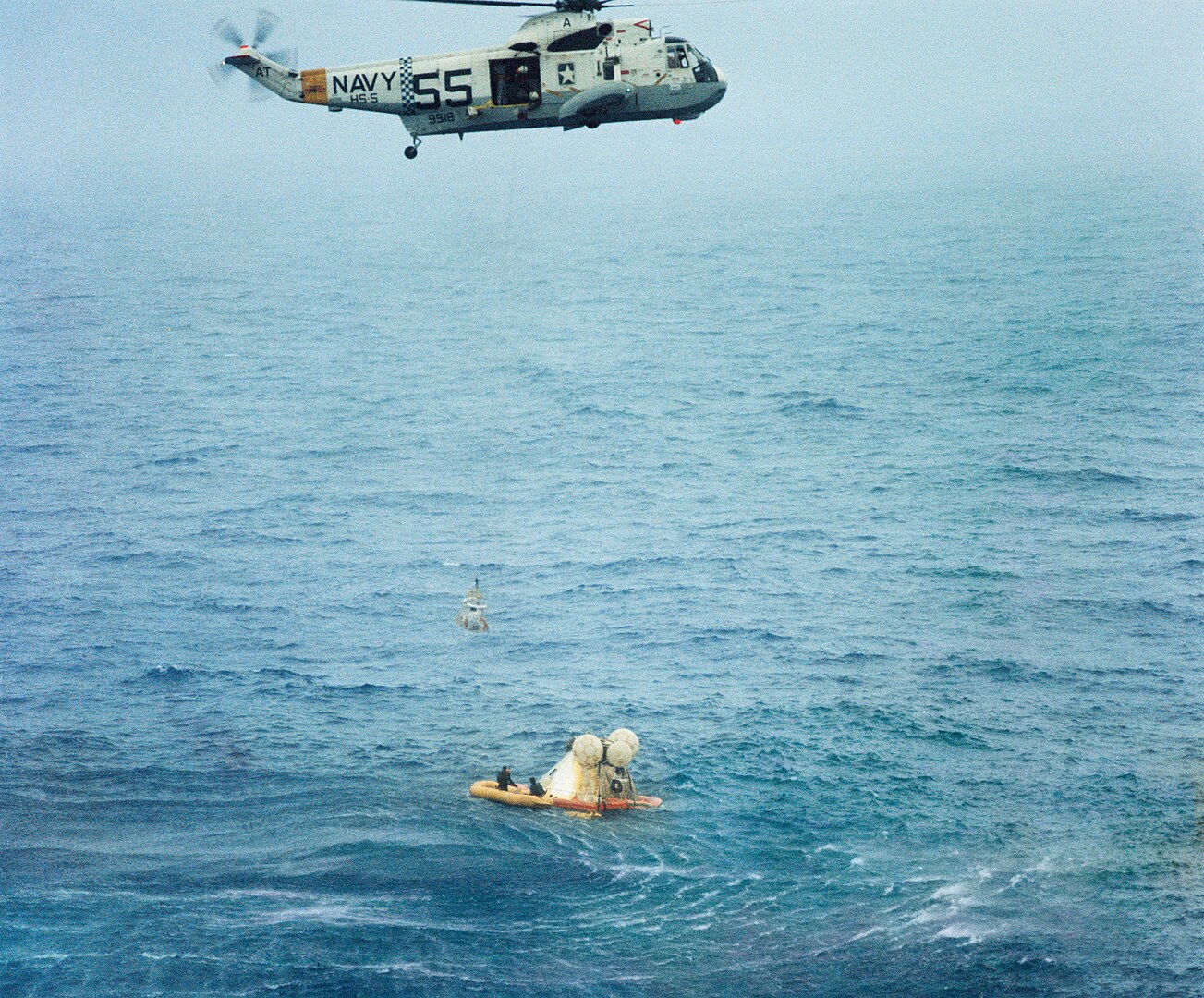

As Apollo 7’s mission was coming to an end after 11 days in space, the crew prepared the Command Module (CM) for re-entry. After the crew performed system checks and ensured the spacecraft’s heat shield was intact, which was critical for surviving the intense heat of re-entry, the Service Module was ejected. The spacecraft performed a deorbit burn with CSM to slow down the thrusters and begin the descent, adjusting the trajectory to ensure a splashdown over the Atlantic Ocean. To further slow the spacecraft to a safe speed, three main parachutes were deployed at 10,000 ft, and Apollo 7 had a controlled and gentle splashdown into the Atlantic Ocean. Apollo 7 splashed down at 7:11 a.m. EDT on October 22, 1968, approximately 200 nautical miles south of Bermuda. Apollo also gave NASA the first live TV broadcast from space, which took place on October 14, 1968.

Post Splash

After the mission’s success, Walter Schirra, Donn Eisele, and Walt Cunningham were awarded NASA’s Exceptional Service Medal. The awards were presented on November 2, 1968, during a ceremony at the LBJ Ranch in Johnson City, Texas, by President Lyndon B. Johnson. By 1970, the Apollo 7 Command Module was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution for preservation. After the Smithsonian acquired the spacecraft, it was loaned to the National Museum of Science and Technology in Ottawa, Ontario. The Apollo 7 Command Module was returned to the United States and is currently on display at the Frontiers of Flight Museum in Dallas, Texas. There, it remains a key exhibit, preserving its legacy in space exploration history.

Today in Aviation History is a series highlighting the achievements, innovations, and milestones that have shaped the skies. All the previous anniversaries are available HERE.

Related Articles

"Haritima Maurya, pen name, ""Another Stardust,"" has been passionate about writing since her school days and later began sharing her work online in 2019. She was drawn to writing because of her love for reading, being starstruck by the art of expression and how someone can make you see and feel things exclusive to their experience. She wanted to be able to do that herself and share her mind with world cause she believes while we co exist in this beautiful world least we can do is share our little worlds within.

As a commercial pilot, Haritima balances her passion for aviation with her love for storytelling. She believes that, much like flying, writing offers a perspective beyond the ordinary, offering a bridge between individual experiences and collective understanding.

Through her work, ""Another Stardust"" aims to capture the nuances of life, giving voice to moments that resonate universally. "

Be the first to comment

Graphic Design, Branding and Aviation Art