By Pete Mecca

On Dec 6, 1941 a flight of thirteen B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bombers lifted off at 15 minute intervals from Hamilton Field near San Francisco. Ahead lay a monotonous fifteen hour flight to Hawaii, and the flyboys were not in a good mood. Before takeoff uncomfortable steel protective plates had been hastily welded to the backs of their seats. The steel plates would later save their lives.

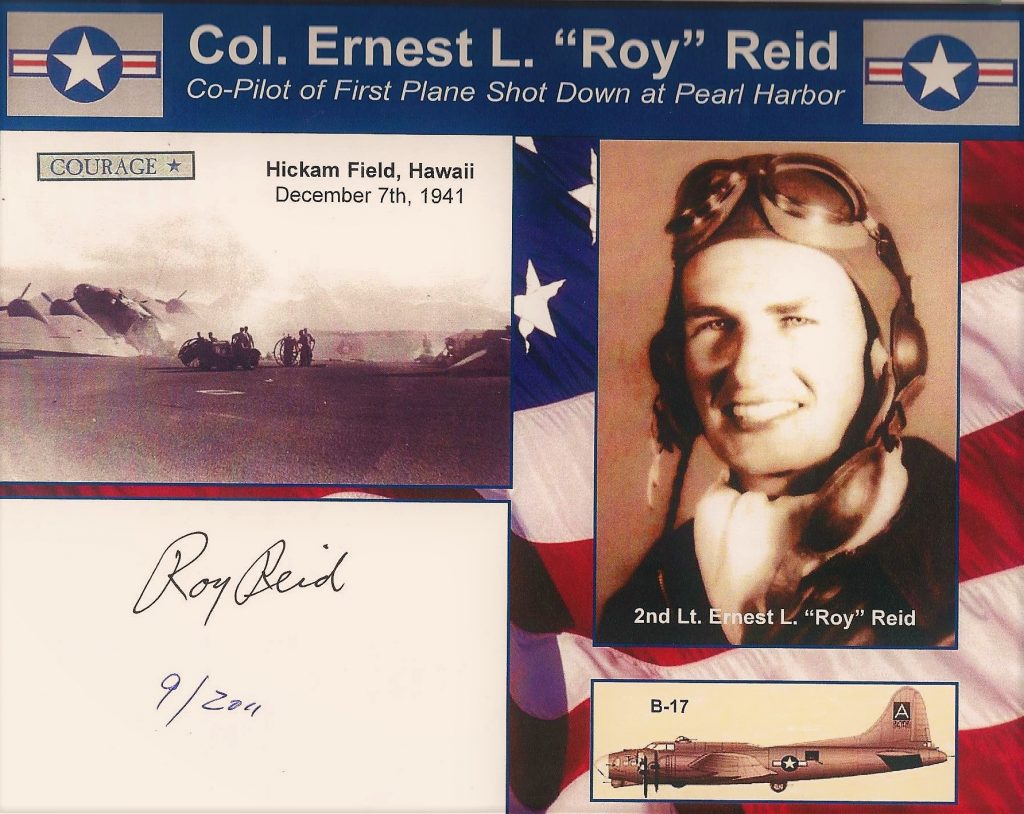

A young 2nd Lieutenant, Ernest ‘Roy’ Reid, copiloted one of the B-17s and vividly recalls their arrival at Pearl Harbor. “It was 0800 on Dec 7, 1941. We were on a long base leg approach to Hickam Field when I spotted thick black smoke churning above the harbor. Captain Swenson, the pilot, had previously flown to Pearl, so I asked him about the smoke. Swenson replied, ‘Don’t worry about it. That’s just local natives burning off sugarcane.’ But I kept thinking, ‘How in the hell do they grow sugarcane on top of water?’”

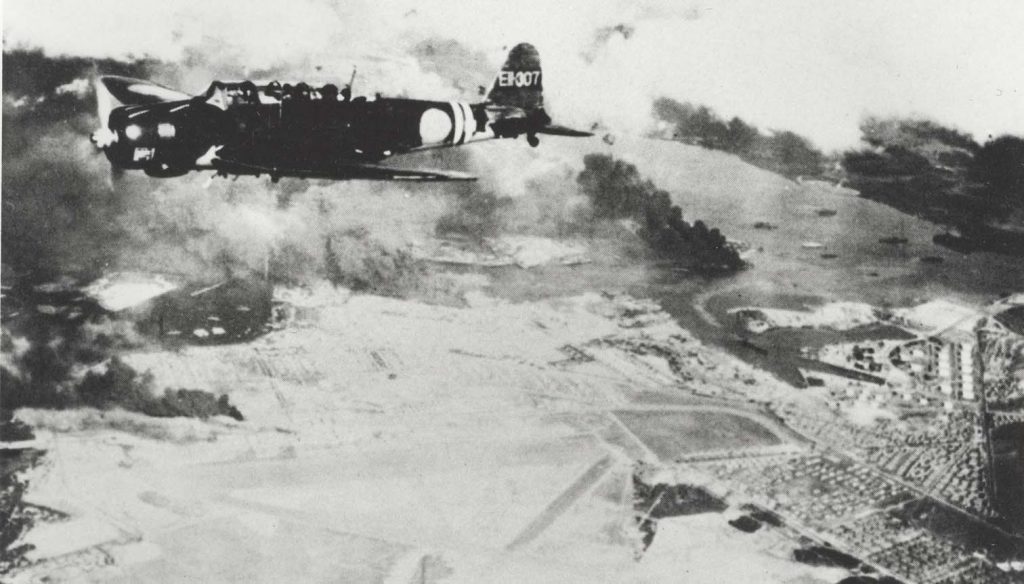

Minutes earlier, Japanese Commander Mitsuo Fuchida had sent the infamous coded signal to the Japanese fleet: ‘TORA! TORA! TORA!’ meaning his attacking aircraft had achieved complete surprise. Bombs fell and sailors died, torpedoes sliced through the water then slammed into the sides of anchored American warships, and neatly parked American aircraft became easy pickings. Second Lt. Reid glanced up to witness the destruction on Hick Hickam Field.

Source: National Archives

Reid said, “We were on our final approach flying at less than 600 feet when I spotted at least six aircraft burning furiously. I knew then that war had come to America.”

Accentuating the obvious, 2 Japanese fighters swung in behind Reid’s hapless B-17 and opened fire. He recalled, “We were unarmed and low on fuel. Tracers riddled our B-17 and ignited the pyrotechnics. Smoke poured into the cockpit. We pushed to full throttle thinking we could escape into cloud cover but flames were licking the backs of our seats so we knew our only choice was to land.” Reid flipped the landing gear switch; the wheels lowered and locked seconds before the bomber hit the runway.

Reid continued, “The bomber bounced so hard we both had to fight the controls to keep the wings level, plus the thick smoke inside the cockpit limited our vision. Then the tail hit and the plane buckled, collapsed, and broke in the middle where the fire had ignited. She separated into two distinct pieces.”

The crew leaped from the inferno and sprinted for the nearest hangar. Reid’s Flying Fortress was most likely the first American warplane shot down in WWII.

Reid is still saddened by one incident: “Our flight surgeon, 1st Lt. William Schick, had a leg wound but managed to get out. As he ran for cover a Jap plane fixated on Schick then fired on him. Schick took a direct hit in the head and later died at a hospital.” The Japanese pilot, however, Takashi Hirano, flying incredibly low to strafe the unfortunate crew, lost control of his fighter after the propeller blades cut into the runway. Hirano crashed and burned.

The remaining crew darting inside a hangar. Reid said, “There was an ill-tempered army sergeant handing out weapons and ammo. We snatched up pistols and clips of ammo then headed out a side door. The sergeant saw us and screamed, ‘You have to sign for those weapons!’ We yelled back…uh, well, you can’t print what we yelled back.”

At a nearby hospital Reid’s aircrew witnessed the real horrors of war. He recalled, “The wounded were pouring in, men with missing arms and legs, several horribly burnt, all screaming in agony. The surgeons and nurses did their best to cope against impossible odds. I’m not normally upset by seeing accidents or even death, but that morning was a bit too much. I sat down on the hospital steps and collected my thoughts before I could get moving again.”

Ernest “Roy” Reid did indeed ‘get moving’ again.

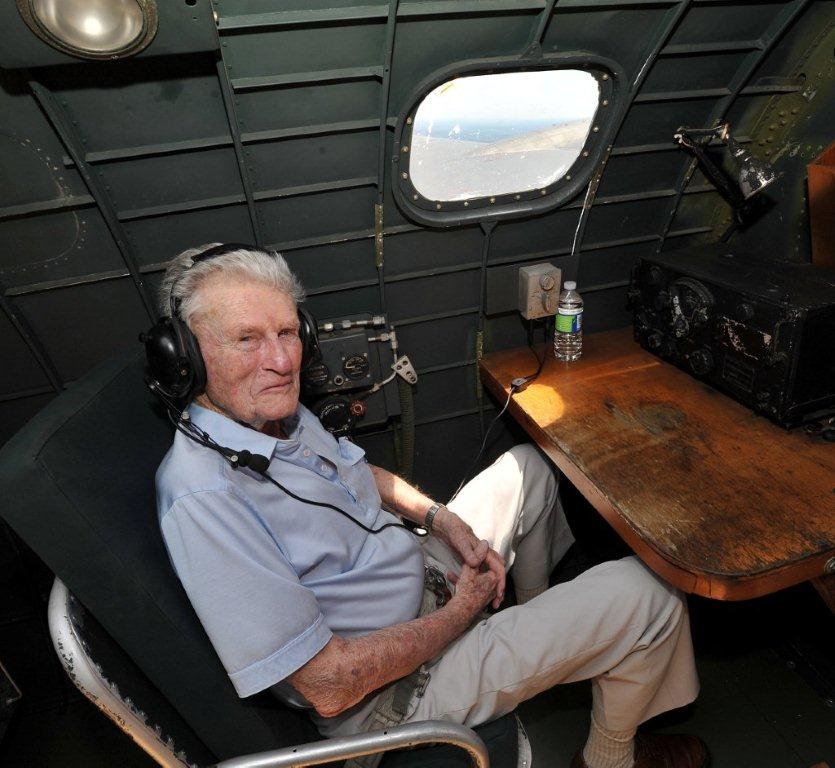

He provided comfort and aid to injured civilian and military personnel before, during, and after the Japanese second attack wave before eventually co-piloting another B-17 to Australia. From Australian, Reid flew copilot on bombing runs and reconnaissance missions. Promoted to Captain, he commanded his own B-17 out of Seven Mile Airfield on New Guinea and completed 50 perilous missions, including against the heavily defended Japanese stronghold at Rabaul. On one mission, Reid and his crew were bushwhacked by 8 Japanese Zeroes. A few went down in flames; the rest gave up, Reid said, “I thought we were goners, but the gunners did a great job and cleansed the sky of Zeroes.”

An aviation addict, Reid also logged flight time in a P-38 Lightning, P-51 Mustang, F-4 Hellcat, a P-47 Thunderbolt, and a British Spitfire. Asked how a bomber pilot managed to log time in fighters, Reid replied, “That was easy. The fighter jockeys wanted to fly a B-17 and I wanted to get behind the controls of their fighters. So, we swapped seats for what we referred to as ‘orientation flights’.” Asked if the ‘orientation flights’ complied with regulations, Reid stated, “Well, we sort of gave each other permission.” Did the same hold true for the British Spitfire? With a big grin planted on his face, Reid replied, “I sort of stole the Spitfire.”

The day after their B-17 burned into two pieces on Hickam Field, Reid and his crew boarded the destroyed bomber to salvage whatever they could. Reid never complained about steel plates again. He found four Japanese bullets embedded into the back of the copilot seat.

Colonel Roy Reid was called home for his Final Inspection on September 18, 2015.

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran. For story consideration visit his website at VETERANSARTICLE.COM and click on “contact us.”

Related Articles

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.

Be the first to comment

Graphic Design, Branding and Aviation Art