By Pete Mecca

In the year 1427, celebrated Vietnamese patriot Le Loi defeated the occupying Chinese soldiers of the Ming Dynasty. Considered God-like by the Vietnamese, Le Loi’s birthplace village of Lam Son is regarded as consecrated ground. Le Loi became a much loved Emperor later in life.

Fast forward 544 years to 1971: The Army of the Republic of Vietnam – the ARVN, commenced a major operation into Laos along Route 9. Their mission was to cut the lines of communication along the North Vietnamese infiltration system known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail and to destroy the supply depot at the crossroads village of Tchepone. The battle is remember as Lam Son 719, the name Lam Son in reverence of Le Loi’s birthplace, 71 denoting the year 1971, and the number 9 signifying Route 9, the main road utilized in the attack.

Earlier, on December 29, 1970, the Cooper-Church Amendment was passed by Congress to restrict the use of American combat troops in Laos and Cambodia. Airpower was authorized. Even with American airpower, a lack of leadership and coordination by the Vietnamese hierarchy resulted in a military disaster. For American airmen and equipment, the cost of the operation was heartbreaking. Helicopter losses: 168, another 618 damaged. Seven fixed-wing aircraft were lost. American choppers flew more than 160,000 sorties, South Vietnamese choppers about 5,500 sorties. B-52s flew about 1,358 sorties and dropped over 32,000 tons of bombs. Nineteen US Army pilots lost their lives, 59 wounded, and 11 missing in action. Six Air Force pilots died and 1 Navy pilot was killed. In all, 253 Americans were killed in action, 1,149 wounded, and 38 missing in action. At first taken by surprise and forced to retreat, the enemy troops regrouped then took advantage of South Vietnamese hesitation and indecision. Men, material, anti-aircraft guns, and support personnel poured into the void. Enemy forces accepted heavy casualties to push the South Vietnamese Army out of Laos and back into their own country. The ARVN lost 60% of their tanks, 50% of their armored personnel carriers, over 50 105mm and 28 155mm howitzers, and casualties into the thousands.

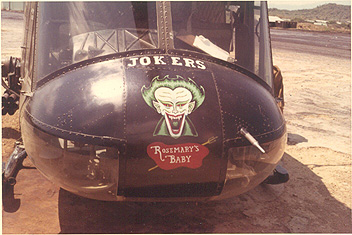

“The performance of the gun platoon, call sign “Joker,” from the 48th, was specifically noteworthy and won tremendous praise from everyone involved. They were admired for their total dedication to the fact they were flying outdated UH-IC model gunships. “On February 20, 1971, the unit was directed to fly an emergency resupply mission in support of South Vietnamese forces in an area some 25 kilometers southeast of Tchepone, Laos. As the mission was being completed and the aircraft were clearing the area, the “Joker” gunships encountered a crew-served ZSU-23-2 anti-aircraft gun. They immediately established themselves in a tactical pattern and initiated their attack on the gun emplacement.”

NOTE: The ZSU-23-2 is a Russian-made twin-barreled auto cannon. Along with the 37mm M1939, the ZSU-23-2 was the most frequently encountered anti-aircraft weapon by American aircraft. Given that 83% of USAF planes were downed due to ground fire, the ZSU is probably responsible for hundreds of American planes lost. Lester continues:

“Although they began receiving heavy fire from other anti-aircraft weapons and small arms positioned to protect the ZSU-23-2, they continued their attack, making numerous passes in an attempt to destroy the gun.

As they were executing their last pass against the gun and expending their remaining ordnance, the trail aircraft was hit and immediately burst into flames. The pilot, CWO Jon Reid, continued his attack inbound toward the gun emplacement, but as the flames grew, he attempted to land the aircraft in a nearby clearing. With the flames now almost completely engulfing the aircraft, it crashed into the trees and rolled into a clearing, coming to rest inverted. “The team leader made several attempts to land next to the downed aircraft to determine the status of the crew and extract any survivors, but was finally forced to depart the area due to low fuel, extensive damage to his aircraft, and a severely wounded crewmember. Even though he had two of his three onboard radios destroyed by enemy fire, he continued to coordinate with other aviation assets in the area to support the rescue effort, but due to intense enemy fire and the withdrawal of friendly ground forces from the area, all attempts proved unsuccessful. “The crew of that aircraft: CWO Jon E. Reid, the pilot; Capt. David M. May, copilot; Sgt 1st Class Randolph L. Johnson, the crew chief; and Staff Sgt. Robert J. Acalotto, door gunner – were all listed as missing in action.

“In 1994, 1996, and 1998, U.S. and Laotian investigators interviewed villagers who had been in the area at the time of the crash. The recovery team initiated an excavation that recovered human remains, as well as portions of an identification tag with the name “May, David M.” Analysis of the remains and other evidence, enabled the Army Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii to confirm the identification of Capt. May and CWO Reid.

“The remains of Jon Reid and David May were interred at Arlington National Cemetery on January 14, 2000 after being classified as missing in action for almost 29 years. The graveside service in the morning began by a fly-by of 4 HU-1 helicopters from the 12th Aviation Battalion at Davison Army Airfield. As we all stood by the caisson bearing the flag draped casket of our friends, the distinctly familiar, reverberating slap of Huey rotor blades could be heard in the cold morning air. As we looked to see the aircraft flying toward us from the Potomac River, up the rolling slopes of Arlington National Cemetery, the sight and sound briefly carried us, in thought, back to earlier times and places where we last stood together as younger men, who were proud, strong, confident, and ‘invincible.’

“I served with Jon and Dave in the 48th Assault Helicopter Company. The 48th was a very close organization and we seem to have grown even closer through the years. Our commander, and many members of the unit are here today, others were unable to be here, but share our sorrow and asked me to read this verse from a poem titled “The Fallen” by Laurence Binyon: “They went with songs to battle, they were young, straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow. They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted, They fell with their faces to the foe. They shall not grow old, as we grow old, Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn, At the going down of the sun and in the morning, we will remember them.”

Thus the story of just one chopper; thus the story of just one crew, lost in combat on February 20, 1971. Almost 12,000 America helicopters of all descriptions were deployed to Vietnam. In all, 5,086 were lost. The Huey still stands as the icon of the helicopter war in Vietnam. Over 7,000 Huey’s were ‘in-country’, almost all US Army, 3,305 of them were destroyed. Huey pilots flew 7,531,969 missions, most likely the most combat flight time of any other aircraft in the history of warfare.

Approximately 40,000 men flew choppers during the Vietnam War. Of Huey pilots, 2,202 were killed in combat, along with 2,704 crewmembers. Vietnam veterans will always remember the unforgettable ‘whump, whump, whump,’ of the Huey’s rotor blades. It’s like our second heartbeat. Each and every Huey that touched down in Vietnam holds a story, every soldier aboard has a story, every gunner has his story, and millions of those stories will never be heard or written. So read again the story of one chopper, of one crew, because in truth it’s the story of every mission, every pilot, every successful engagement and each failure…the Huey is the story of Vietnam.

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran. For story consideration visit his website at aveteransstory.us and click on “contact us.”