By Pete Mecca

An airfield in northeast Thailand designated as NKP (Nakhon Phanom) during the Vietnam War is actually a Royal Thai Naval Base. The Thais utilize NKP as a home base for river patrols along the murky Mekong River, the internationally accepted border between Thailand and Laos. During American involvement in Southeast Asia, the small township of Nakhon Phanom on the banks of the Mekong quickly developed into a Wild West boomtown.

As American money flowed into the once sleepy township, so did new businesses and, of course, bars. One favorite hangout was called The Shindig. It was a bit dingy but decently sanitary, and the men stationed at NKP quickly picked up enough of the Thai language to order a cool, or more often than not, lukewarm beer, or instigate a conversation with Thai girls dressed in very short skirts. The females quickly picked up English, or at least the phrase, “G.I., I love you a long time.” American influence meant inflation for the Thais, yet cheap everything for the G.I.s. Ice cold Singha beer became an American favorite and is now offered in Thai restaurants all across America. However, to avoid a plethora of weird body dysfunctions, I’d leave the Mekong Whiskey on the shelves if I were you.

But there was a war raging across the Mekong River. Laos was home to the infamous Ho Chi Minh Trail, a spider web network of trails, paths, and wide dirt roads used by the North Vietnamese to infiltrate men and materials into South Vietnam. The fighting was fierce, every mission a deadly risk, and every sacrifice improperly disclosed because Laos was a “secret war” waged by men sworn to secrecy in a battle dominated by CIA operatives and a huge cast of supporters, all living and operating clandestinely.

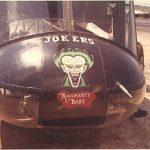

On the night of July 8, 1969, U.S. Air Force Major James Sizemore, pilot, and his navigator, Major Howard Andre Jr., completed the final checklist on their World War II-era A-26 Douglas Invader. The vintage fighter bomber, painted solid black with no identification markings, was part of a hush-hush interdiction campaign against Communist North Vietnam’s well-protected Ho Chi Minh Trail through Laos and Cambodia.

Throttling both engines to full power, Major Sizemore held the Invader stable until achieving proper lift for takeoff. Banking eastward towards the Trail, Sizemore, and Andre readied the A-26 for a nighttime armed reconnaissance mission.

The A-26 Invader was a formidable aircraft. A maneuverable and solid gun platform, an Invader sported eight .50 caliber machine guns in its nose, three .50 calibers in each wing, and during WWII the twin .50 calibers on the front turret could be locked into a forward position for the strafing impact of sixteen forward-firing .50 caliber machine guns. Toss 4,000 lbs. of bombs into the bomb bay and/or rockets attached to both wings, then it becomes easily understandable nobody wants to be on the receiving end of an Invader mission.

Over the rugged mountainous Communist-held region of Xiangkhouang Province, Laos, the two American airmen spotted enemy personnel and vehicles. Rolling in for a strafing run, the A-26 Invader was immediately hit by anti-aircraft fire. She never recovered. Continuing straight down, the Invader exploded upon impact into the mountainous terrain. With the area totally under enemy control, a determined recovery effort was not possible. No parachutes were seen; no emergency beepers heard; the boys were gone, lost in a war in which both sides denied involvement.

Majors James Sizemore and Howard Andre were listed as Killed in Action/Body not recovered. By the war’s end, almost 600 American aviators and ground special forces personnel vanished in the countryside of Lan Xang Hom Khao (Kingdom of a Million Elephants with a White Parasol) — Laos.

On that same night back at NKP, a young airman had just finished his 12-hour shift in the Intelligence building, or more than likely, was already neck-deep in a poker game at the base club, unaware another Invader had gone down. He was in his 16th month at NKP with two more months to go before reporting to Saigon, Vietnam, for yet another year of the war.

An aviation enthusiast and military historian, the young airman couldn’t believe his good luck when he first arrived at NKP. The relatively small airbase was a throwback to a WWII Pacific island landing field, dusty or muddy depending on the weather, cut from the thick jungle, isolated, with a flight line clogged with aircraft from a bygone era: the 1950s era Prop-driven AlE Skyraider, the lovable C-47 Gooney Bird, and the celebrated A-26 Invader. For the next 18 months, this young airman would plead, even lie, to catch a combat “hop” aboard an A-26. He never succeeded. The best he ever managed was totally unauthorized flights on Huey or Jolly Green Giant rescue helicopters until his superiors found out and grounded him due to his Top Secret Crypto security clearance.

After 30 months in Southeast Asia, the airman returned home. He had been one of the lucky ones, granted a new lease on life to live out that life as best he could. A college degree; marriage, a kid, divorce, single parenthood, and another marriage that endured lay in his future. Still, the nagging memories of his return from Vietnam to an uncaring and sometimes hostile public kept his thoughts bottled up. Even worse, he lost all respect for a government that had abandoned its military when that same military had been asked to do the impossible.

In time a smidgen of respect returned for the federal government due to the leadership of men like Ronald Reagan and WWII veteran George Bush. Yet, that smidgen of respect disappeared into the quicksand of political correctness and a society based on government dependency instead of individualism and patriotism. He no longer recognized the country he once proudly fought for, and if need be, die for.

In 1993, joint search teams from the United States and the People’s Democratic Republic (Laos) discovered a crash site of an A-26 Invader. Due to many factors, a complete excavation was not possible at the time. In 2010 another team returned to the crash site and began an appropriate excavation. They unearthed personal belongings, United States Air Force equipment, additional aircraft wreckage, and the human remains linked to Sizemore and Andre.

The Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC), using forensic, dental and DNA techniques, confidently identified the remains as belonging to Majors Sizemore and Andre. After 41 years in the jungle, the boys were coming home. In August of 2013, family, friends, and military dignitaries gathered at Arlington National Cemetery as Majors Sizemore and Andre were honorably laid to rest. Due to sequestration, a military flyover was not allowed.

Warrior Flight Team and their affiliate, Warrior Aviation, both non-profit organizations, stepped to the forefront to honor Sizemore and Andre. Using their private vintage military aircraft and personal bank accounts to pay for it, the flyover included an A-26, P-51 Mustangs, and privately owned jets for the missing man formation.

Upon hearing of yet another national humiliation heaped upon the men and women of our military, that once-young airman decided to write the story of, and a special tribute to, Air Force Majors Sizemore and Andre. You guessed it, that sometimes undisciplined and poker-playing airman was yours truly.

I may have attended a briefing with Sizemore and Andre, it’s feasible I may have passed them in one of the hallways inside The Project (Top Secret Intelligence Building), and it’s more than possible that I rendered them a salute on one of many dirt pathways at NKP. What rips at my gut is the miserable fact that these two heroes of the skies were not allowed a proper flyover at Arlington because of the indecisiveness and wretched bickering among politicians in Washington, D.C.

Notwithstanding, welcome home my brothers. You did your duty; you did what had to be done, and may you finally rest in peace.

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran. For the story, consideration visit his website at aveteransstory.us and click on “contact us.”

NKP I was a Captain flying C-97 stratocruiser into NKP. Super secret at the time. We departed England AFB with four A-26’s following us. They had no long range nav equip only fm radios and plenty of .50 cal guns. A wild bunch they were, heros all. They were ready for a fight did their job well. We led them to NKP and flew the Mecong daily. NKP at that time was a tent base. We unloaded their ammo and equipment and left NKP. They stayed and fought with their A-26’s We knew it was a tough and dangerous mission for them, but they were up to it. God bless all of them