The Museum of Science and Industry (MSI) in Chicago stands as one of the most prestigious science museums not only in the Midwest, but in the United States as a whole. From tractors and automobiles to trains and the German U-boat U-505, the MSI, also known in the past as the Rosenwald Museum, has been host to several aircraft in its collection since the founding of the modern museum in 1933, which was based on The Palace of Fine Arts at the 1893 Columbian Exposition’s “White City.”

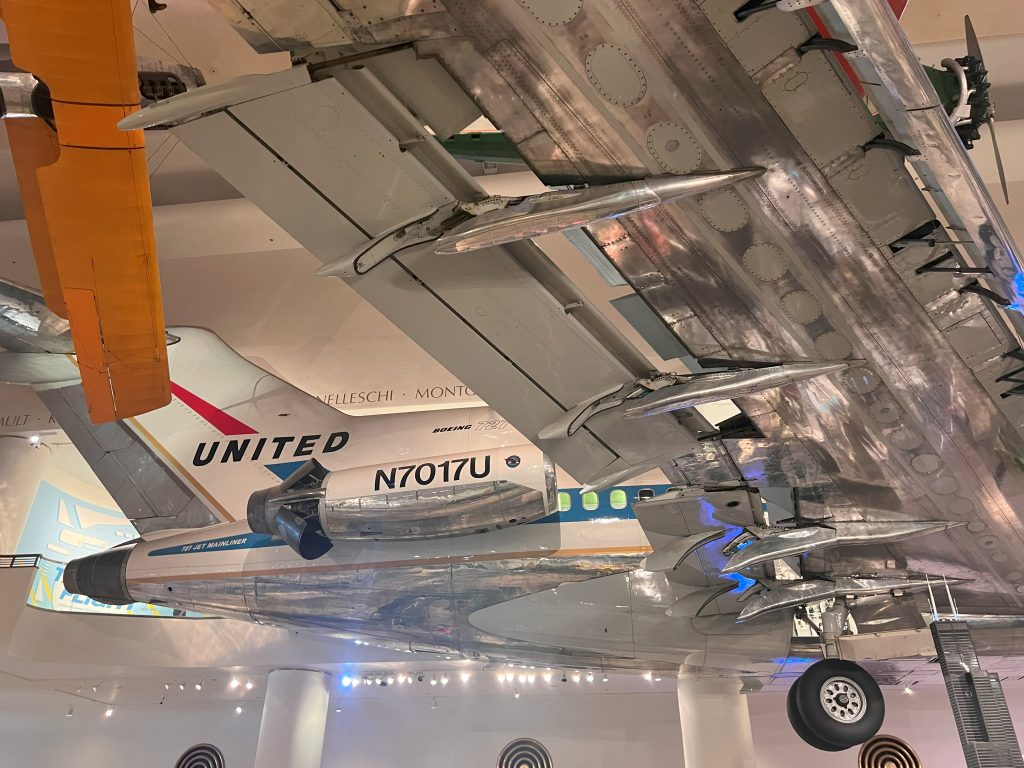

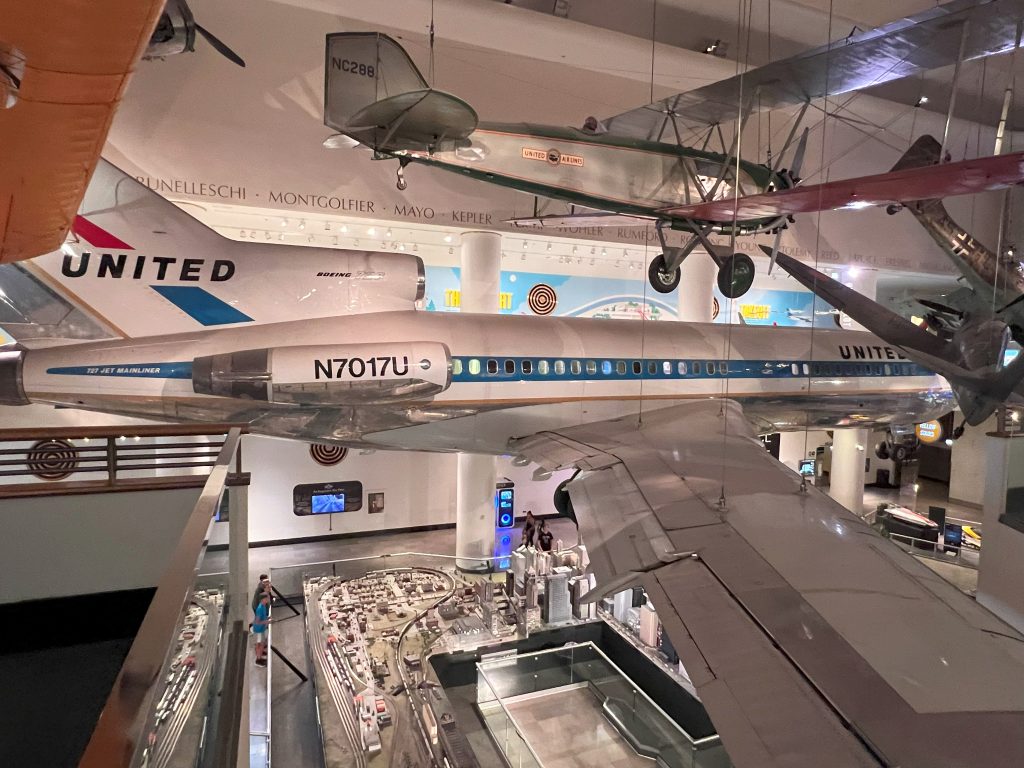

Inside the museum one can find a former United Airlines Boeing 727-100 (registration number N7017U) hanging from the second story balcony. This aircraft, built as construction number 18039, was delivered from the Boeing factory at Renton, Washington to United Airlines in May 1964 and flown with the company for the entirety of its nearly 30 year-long operational life. During its service for United, N7017U logged 66,000 flight hours, and carried up to 3 million passengers over 28 million miles.

In 1991, N7017U was retired from United Airlines’ operational fleet, but instead of being scavenged for parts and scrapped, N7017U was donated to the Museum of Science and Industry. Transferring the aircraft on paper was one thing; delivering it to the museum was more complicated. The closest airport to the museum that could comfortably accommodate a Boeing 727 is Chicago Midway Airport, but with eight miles of city blocks between Midway Airport and the museum on Chicago’s Lakeshore Drive. However, in 1992, Chicago still had an active airport on the lake front; Merrill C. Meigs Field (which later closed in 2003 and is now the site of Northerly Island Park), situated next to the Adler Planetarium and the Field Museum. Landing the 727 at Meigs Field would be a challenge, as the runway there was just 3,900-feet (1,200 m), but the airline had a capable crew to take N7017U on its final flight, with Captain B.C. Thomas and First Officer Bill Loewe at the controls, and Second Officer Greg Hammes at the flight engineer’s station.

On September 28, 1992, the Boeing 727 took off from Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport on the short flight to Meigs. After a low pass for the public and the press that had gathered to watch, Captain Thomas made the approach on runway 36 north. The aircraft had to land into a 15-knot crosswind, and landed at a speed of 115 mph, well below the standard landing speed of between 150-175 mph. But the aircraft touched down and stopped nearly 2,000 feet down the runway. (Video of the landing can be seen HERE).

After its final touchdown, the 727 was loaded onto a barge and towed to Burns Harbor, Indiana for temporary storage as the museum prepared to get their exhibition space ready to fit the 30-year-old airliner. Meanwhile, the aircraft was cleaned and the interior stripped out in preparation for its move back across Lake Michigan to the Museum of Science and Industry. On September 22, 1993, almost exactly one year since the plane’s last flight into Meigs Field, the 727 was transported by barge to 57th Street Beach, just across Lakeshore Drive from the MSI. On the beach, a special ramp was put into place for the aircraft to be towed off the barge and back on shore. For many older residents of Chicago, it was similar to the 1954 arrival of the museum’s WWII German U-boat, U-505, which was also towed across Lake Michigan before crossing Lakeshore Drive to reach the museum.

After crossing Lakeshore Drive, the Boeing 727 was towed through the museum’s north parking lot (since replaced by an underground lot), then onto Cornell Drive in preparation for its move through the west side of the museum building. In order to facilitate the move, the museum had to temporarily remove one of the two columns at the West Entry before the aircraft was disassembled onsite and on November 18, the fuselage was moved in through the entrance. Because the aircraft would be hanging from the structure of the Transportation Gallery’s balcony, the left wing was removed from the aircraft, with only the right wing brought inside for reattachment, along with the tail stabilizers and the engines. Once inside, the aircraft was draped off, and a team of painters restored the original 1960s-era United Airlines livery that the aircraft was introduced into service with. The aircraft is even still operational to some degree, as pneumatic and air pressure systems in place of the hydraulic system still actuate the 727’s landing gear, flaps, slats, rudder, elevators, and right aileron! If you happen to be present when the landing gear and flaps swing out from the old airliner, it is truly remarkable. The MSI also created a video about the extraordinary effort to move the massive airliner inside their museum HERE.

Today, Boeing 727 N7017U is the centerpiece of the museum’s Take Flight exhibit, with millions of visitors a year going through the aircraft. The passenger cabin has been replaced by exhibits about the science behind flight. The cockpit is protected by a transparent panel, while sections have been cut into the fuselage to allow for easier access for people with disabilities. On the nose of the cockpit section, the aircraft also bears the name of Captain William R. Norwood, who served in the US Air Force flying B-52s in Strategic Air Command before he became the first African American pilot hired by United Airlines in 1965, at a time when hiring Black pilots was still controversial. Norwood went on to have a 31-year career with the airline and has become very active in aerospace education programs since his retirement from United.

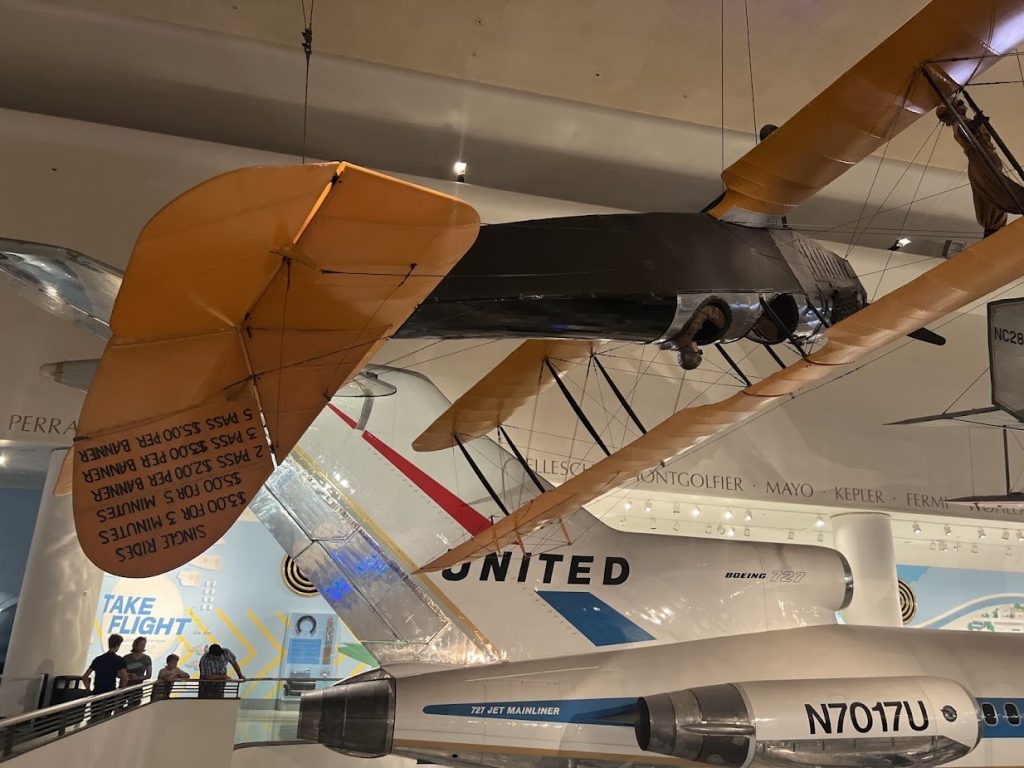

Suspended alongside the Boeing 727 from the ceiling are a number of historically significant aircraft, two of which have been part of the museum now for over 90 years. One of these is a Curtiss JN-4D Jenny displayed inverted with the mannequin of a wing-walker standing between the two wings, while the mannequin of a pilot sits in the rear cockpit. This particular Jenny was one of thousands built for the United States Army Air Service during the First World War, and which, following the war’s conclusion, were now surplus and available for purchase on the private market. The aircraft was originally constructed with the production number 533, flown with the USAAS serial number 5368, and was later purchased and flown by barnstormer John Lewis Brown from Momence, Illinois, about 50 miles south of Chicago. Brown had served in the Army Air Service during WWI as a flight instructor at Chanute Field in Rantoul, IL, and following his purchase of the Jenny, Brown flew across the Midwest offering rides to paying passengers or banner towing for numerous events, listing his prices on the Jenny’s rudder. On the lower left wing, the aircraft would eventually carry the civil registration code 2421 (short for NC2421).

During the Century of Progress World’s Fair in Chicago, held from 1933 to 1934 in order to mark the city’s centennial, Brown flew the old Jenny in aerobatic demonstrations over the sprawling event. However, by the early 1930s, many of the surviving Jennies were now considered to be quite old, even if they were only 15-year-old airframes. As a gesture of goodwill, Brown donated his Jenny to the Rosenwald Museum/Museum of Science and Industry to join the museum’s permanent collection. Besides the occasional overhaul, it has remained on display in the museum ever since.

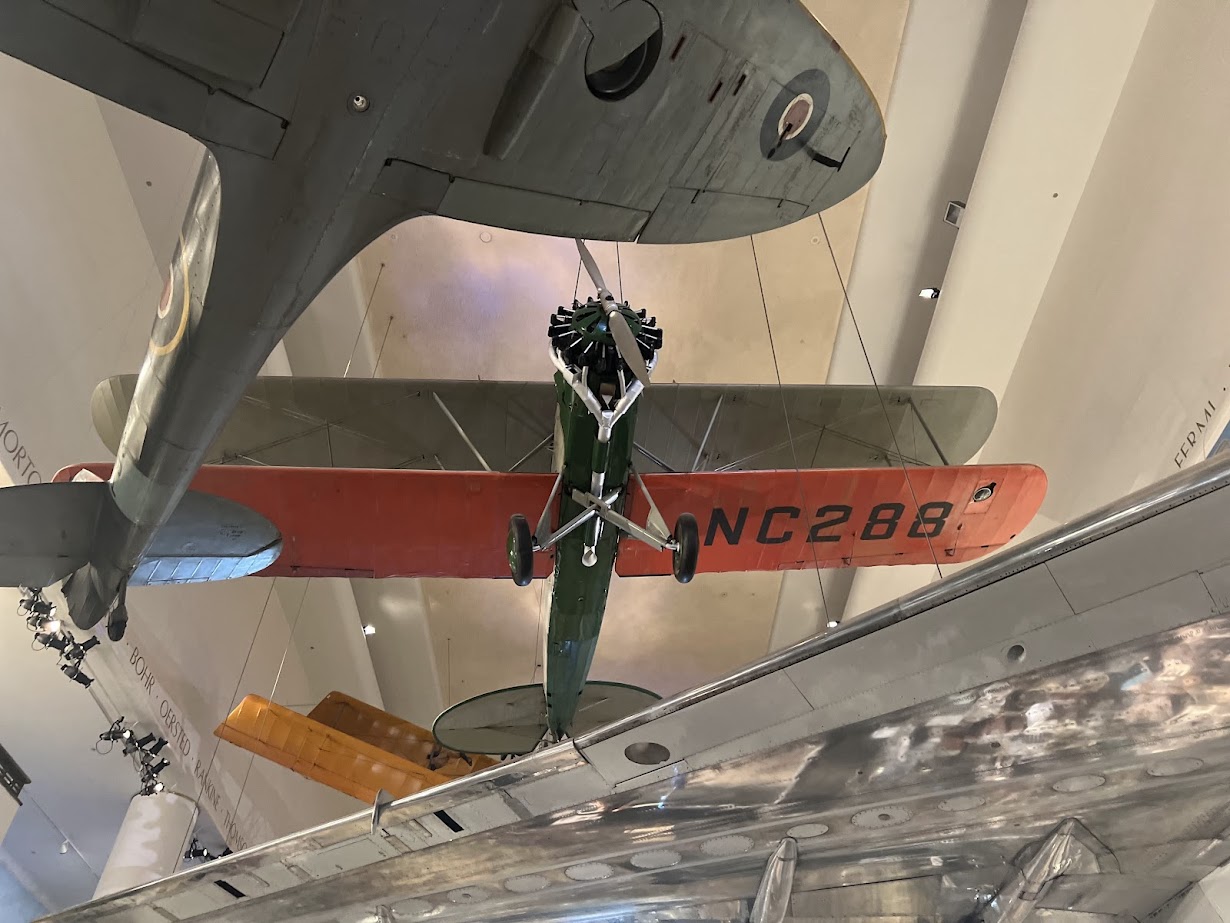

The other aircraft acquired during the Century of Progress exposition was a Boeing Model 40 mailplane that is currently suspended alongside the Jenny and the Boeing 727 in the Transportation Gallery. First flown on July 25, 1925, the Model 40 was designed specifically for the air mail service in order to replace the aging WWI-era American-built de Havilland DH-4s modified for use on the burgeoning air mail routes that spanned the North American continent, with the air mail pilots being lauded as though they were the latter-day Pony Express. Flown by a single pilot in an open cockpit, the single engine aircraft could carry two passengers and up to 1,200 lbs. of airmail in an enclosed cabin.

Around the same time of the development of the Boeing Model 40, the Boeing Airplane Company established its own air-mail service, Boeing Air Transport (BAT) in 1927 (which was later became United Airlines), and acquired the rights to fly an airmail route from San Francisco to Chicago using its new Model 40s. Among the Model 40s of Boeing Air Transport/United Airlines was the aircraft now in Chicago, Model 40B construction number 899, registration NC288. From June 1927 to 1933, NC288 logged over 6,000 hours on the San Francisco – Chicago route, crossing the Sierra Nevada, the Great Salt Lake Desert, the Rocky Mountains and the Great Plains, following the railroads that airmail pilots called the “iron compass.” As part of their contribution to the Century of Progress’ Wings of a Century exhibit, United Airlines sent out Boeing Model 40B NC288 to be placed on prominent display for the exposition.

By this time, much like the aforementioned Jenny, the rapid pace of aeronautical advancements had already outmoded the Model 40 in favor of a new design by Boeing, the Model 247 airliner, which was among the first twin-engine, all metal monoplane transports with retractable landing gear. As such, it was decided to donate the Boeing Model 40B to the Museum of Science and Industry, where it has remained to this day, and it is among only two surviving examples of the Model 40, with one example on display at The Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, MI, and another example that crashed in Canyonville, OR on October 2, 1928, was later rebuilt by Addison Pemberton of Pemberton and Sons Aviation from 2000 to 2008 to airworthy condition, and is now part of the Western Antique Aeroplane and Automobile Museum in Hood River, OR.

Perhaps the biggest draw for WWII aviation enthusiasts at the MSI is the institution’s Junkers Ju 87 R-2/Trop. Stuka, one of just two examples of the infamous dive bomber to survive the war intact rather than being pieced together from wreckage that was exposed to the elements for decades after the war. Constructed as an R-2 variant with the Werknummer 5954, it was assigned to III. Gruppe (Third Group) of Sturzkampfgeschwader 1 (StG 1; Dive Bomber Wing 1), deployed to North Africa, and given the fuselage code ‘A5+HL’. The aircraft was also fitted with equipment to operate in tropical conditions, such as sand filters for its oil cooler.

According to aviation historian Peter C. Smith, the aircraft received damaged to its Junkers Jumo 211 inline engine and its radiator in aerial combat with Curtiss Tomahawk fighters of No. 3 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force and was undergoing repairs at the Axis-held airfield near Gambut (Kambut), Libya when the airfield was overrun and captured by British forces. While some captured aircraft were made airworthy for flight evaluation to determine their strengths and weaknesses, WkNr. 5954 was determined to be of little use for this purpose, given its combat damage, with the engine having a large bullet hole in both its crankcase and one of its cylinders. Instead, the aircraft would be shipped to North America to participate in war bond drives across Canada and the United States as part of the British Information Services (BIS) contributions to the Allied fundraising efforts. Upon the war’s conclusion, the BIS, through their offices in Chicago, donated the Stuka to the Museum of Science and Industry to acknowledge the American effort in the Allies’ victory over the Axis Forces.

The museum rebuilt and replaced missing parts of the aircraft, but in 1970, after over twenty years of being suspended from the ceiling of the museum in Chicago, a routine effort to clean off dust from the aircraft went wrong when one of the cables holding the Stuka snapped, causing it fall and receive severe damage. As a result, the Stuka was sent to the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA), then headquartered at Hales Corners, Wisconsin, for restoration. After its restoration was completed, the aircraft was loaned to the EAA’s museum in Hales Corners until 1980, when it returned to the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago for permanent display. In 2015, the aircraft was temporarily lowered from the ceiling to the floor of the museum in order to conduct a 3D scan of the aircraft (which we covered HERE). Many visitors may be intrigued by the fact that the Stuka in Chicago does not display the familiar “wheel pants” seen in countless wartime photos and films, but this is because many Stukas operating from unimproved airstrips often had their streamlined landing gear covers removed to avoid getting clogged with excess dust, sand, or mud in both the North African and Eastern Fronts.

Chasing the Stuka into a dive is yet another remarkable combat veteran of the Second World War, a Supermarine Spitfire Mk I. This particular Spitfire is one of the last aircraft to have fought in the Battle of Britain, but there is more its story than that momentous event in military aviation history. Constructed at the Vickers-Armstrong Woolston factory in Southampton in 1939, it was the second aircraft in Serial Batch P9305-9339 and was the 508th Spitfire ever produced. Assigned the serial P9306, it first flew on January 19, 1940, at Southampton, being accepted into the RAF the following day. The aircraft was kept on reserve with at least three Maintenance Units (MUs), No. 24 MU at RAF Turnhill on January 24, 1940, No. 4 MU at RAF Ruislip in March 1940, and No. 6 MU at RAF Brize Norton on June 27, 1940.

During the Battle of Britain, the aircraft was assigned to No. 74 Sqn at RAF Hornchurch and marked with the name ‘Trinidad’ on its nose. On July 10, 1940, Pilot Officer Peter Charles Fasken Stevenson was flying P9306 when he was credited with shooting down a Messerschmitt Bf 109 and damaging a second one. One month later, Pilot Sergeant Thomas Brian Kirk used P9306, fuselage ZP-H, to shoot down a Bf 110 36 miles east of Harwich. After being involved in further aerial skirmishes but without being credited for further victories, P9306 was transferred to No 45 Maintenance Unit for repairs on September 20, 1940, before returning to No. 74 Squadron and claiming three more victories. By this point, though, the Spitfire Mk Is were replaced in frontline units in favor of cannon-armed Spitfire Mk IIs. On July 18, 1941, P9306 was officially transferred to No. 131 Squadron at RAF Catterick in North Yorkshire, being recoded as NX-M and used primarily for operational training for new pilots, and the aircraft did not see further combat. Three months later, on October 22, the aircraft was transferred yet again to No. 52 Operational Training Unit (OTU) at Aston Down, it was used for further flight training for newly minted fighter pilots in the RAF, which included not only British pilots but pilots from occupied Europe such as Belgium.

After being damaged to the point where it was sent to the factory of Westland Aircraft for repairs, it was eventually flown with No. 61 OTU RAF Rednal on May 4, 1943. As new variants of the Spitfire, such as the Mk. IX, made their mark in the Mediterranean against the Germans and Italians while being powered by newer variants of the Rolls Royce Merlin, the last Mk Is still in service where even phased out of the OTUs. At the start of 1944, Spitfire P9306 was transferred to No. 39 Maintenance Unit at RAF Colerne, and lastly to No. 52 MU at Cardiff, Wales. At Cardiff, it was decided through the British Information Service (BIS) that the aircraft was to be shipped to the United States to go on public display. On August 26, 1944, P9306 was officially allocated to the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, arriving there on September 19, where it has remained on display ever since.

At the end of the east balcony facing the Transportation Gallery stills a full-scale replica of the 1903 Wright Flyer. However, unlike many similar replicas across the country, this one, named the Spirit of Glen Ellyn, actually took flight. Constructed by the Wright Redux Association of Glen Ellyn, Illinois, between July 2001 and 2002, the reproduction was assigned the FAA registration N203WF. On April 27, 2003, pilot Ken Kirincic made the Spirit of Glen Ellyn’s first flight at Clow International Airport near Bolingbrook, Illinois. Later that year, on September 20, the aircraft made an attempt to fly on the lawn of the Museum of Science and Industry, but ironically for the Windy City, the winds were just not strong enough for a sufficient flight attempt. By November 2003, N203WF was officially placed on display for permanent exhibition at the Museum of Science and Industry, honoring not only the spirit of Orville and Wilbur Wright, but also all of the volunteers who dedicated themselves to building the Spirit of Glen Ellyn.

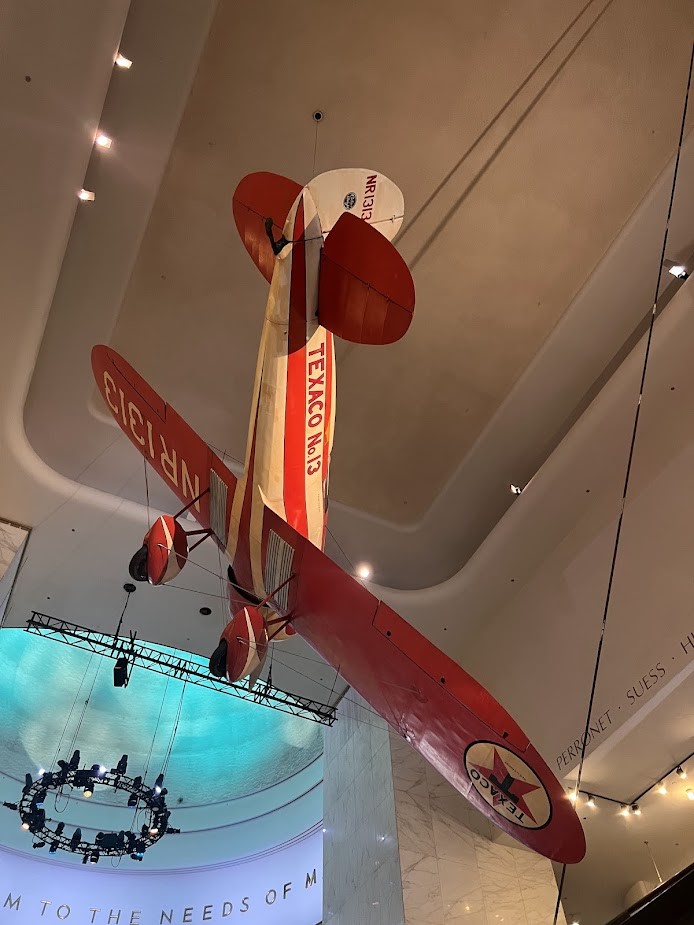

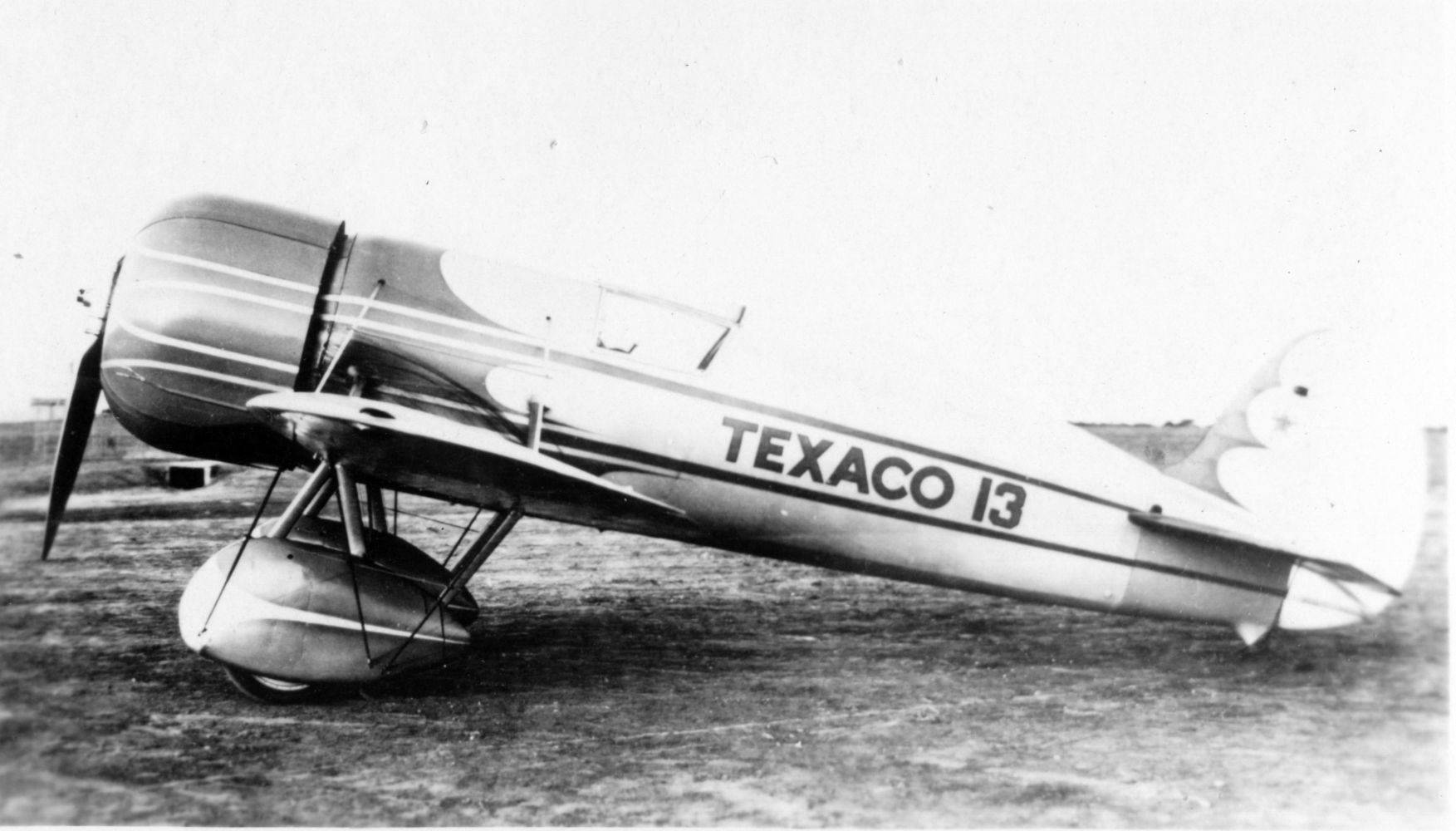

In another wing of the MSI, suspended in a right bank angle above the Musuem’s popular Coal Mine exhibit is what was once one of the fastest airplanes in the world; a Travel Air Type R “Mystery Ship”. Developed by the company that was founded in Wichita, KS by Clyde Cessna, Walter Beech, and Lloyd Stearman, the Type R was developed in such secrecy before the 1929 National Air Races that the press dubbed it the “Mystery Ship”. Only five Type Rs were constructed, but their performance was such that when they were introduced, they were faster than many of the biplane fighters then in service with the US Army Air Corps and the US Navy.

Only two of the five survive today, and the Museum of Science and Industry’s example was constructed as construction number R-2004, N-number NR1313, in 1930 for Frank Monroe Hawks, a WWI flight instructor and barnstormer turned ambassador for Texaco as head of the oil company’s Aviation Division. Powered by a Wright J-6-9 (R-795) Whirlwind, the combination of NR1313, dubbed “Texaco No.13”, and Frank Hawks, who was nicknamed the “fastest airman in the world”, resulted in a record-breaking duo that traveled at blistering speeds. Despite a rocky start with a crash on July 11, 1930, at the factory airfield in Wichita, Texaco 13 was quickly repaired and on August 6, 1930, Hawks flew Texaco 13 from Valley Stream, New York to Los Angeles in 14 hours, 30 minutes, 43 seconds. Just thirteen days later on August 13, the pair flew from Glendale, Los Angeles back to Valley Stream in 12 hours, 25 minutes, 3 seconds, then the fastest crossing of the continental United States.

Over the next 18 months, Hawks and the Texaco 13 Travel Air set numerous speed records, from flying from New York to Detroit, Michigan in 3 hours, 3 minutes on September 9, 1930, to flying from Philadelphia to New York in 20 minutes to deliver the first press photos of the World Series on October 2, which was faster than the wire service for transmitting photographs. People began to say, “Don’t send it by telegraph, send it by Hawks!”

He even took the Texaco 13 abroad, breaking speed records between Miami, Florida and Havana, Cuba before crossing the Atlantic in 1931 aboard the German ocean liner SS Europa to break speed records between London, Paris, Amsterdam, Berlin, Stockholm, Rome, and Budapest. Much of this was done not only to promote Texaco’s aviation products, but to demonstrate that quick air travel between large cities could become a profitable venture.

Though Hawks began the year 1932 with plans to take the Travel Air Texaco No. 13 down to Latin America to set more inter-city records, both he and the aircraft met with disaster on April 7, 1932, when the aircraft crashed on takeoff near Worchester, Massachusetts. Though, Franks was able to prevent a fire by switching off the electrical systems for the aircraft, he severely fractured his nose and jaw against the instrument panel in the violent crash that saw Texaco 13 flipped on its back. Following reconstructive plastic surgery, Hawks had the aircraft repaired but decided to move on to newer aircraft. However, both he and Texaco agreed that the famous aircraft should be selected for preservation. It was donated to the Museum of Science and Industry and remains a symbol of the Golden Age of Aviation. In addition to the original Texaco 13 in Chicago, a full-scale replica of the Texaco 13 can be seen across Lake Michigan at the Air Zoo in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

Several capsules are also on display here, including a high-altitude balloon gondola designed by Swiss brothers Jean and Auguste Piccard which set an altitude record of 61,237 feet on November 21, 1933, piloted by Navy Lt. Cmdr. T. G. W. “Tex” Settle and Maj. Chester Fordney, followed by Jeannette Picard using the same gondola to set the women’s high-altitude record of 57,579 feet on October 23, 1934. Meanwhile, the museum also displays three space capsules in the form of the Mercury-Atlas capsule Aurora 7, flown by Scott Carpenter, the Apollo 8 capsule flown by Bill Anders, Jim Lovell, and Frank Borman to become the first humans to see the dark side of the Moon with their own eyes, and more recently the SpaceX Dragon 1 capsule C113, used twice in space for missions CRS-12 and CRS-17, and which was only placed on display as recently as 2022. Additionally, a full-scale replica of a Gemini space capsule and an Apollo Lunar Module inside the Henry Crown Space Center.

In addition to the aircraft currently on display in the MSI, there have also been several aircraft that have since left Chicago for other museums. These include a Curtiss Model D Headless Pusher replica, NR10362, which is now on display at the Glenn H. Curtiss Museum in Hammondsport, New York, the last surviving Curtiss N-9H WWI naval trainer, now displayed at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, and a SPAD VII, Army Air Service serial number A.S.94099, displayed today in the National Museum of the United States Air Force’s Early Flight gallery in Dayton, Ohio. All in all, the Museum of Science and Industry is a museum definitely worth checking out, with well-maintained aircraft, modern displays, and much more to see and explore, and you can start your exploration through the museum’s website HERE.