by Adam Estes

In the last four years, specialist technicians at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force (NMUSAF) in Dayton, Ohio have refurbished several WWI-era aircraft, including an Avro 504K and Thomas-Morse S4C Scout. While both of these biplanes have since returned to the museum’s Early Years Gallery, work is progressing presently on yet another significant First World War biplane trainer, this being former U.S. Army Air Services Curtiss JN-4D ‘Jenny’ serial number 2805.

Perhaps the most recognizable American aircraft of World War I, the Jenny can trace its roots to a pair of earlier designs emerging from the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company of Hammondsport, New York; the Model J and the Model N (which eventually became a successful naval trainer). A British engineer working at Curtiss, Benjamin Douglas Thomas, combined the best attributes of the aforementioned types, resulting in the Model JN. As an aside, Benjamin Thomas had previously worked for the Sopwith Aviation Company in England, and also helped the brothers William and Oliver Thomas (no relation) at the Thomas-Morse Aircraft Corporation design the S-4 “Scout” single-seat trainer. But I digress; with respect to the ‘Jenny’, Curtiss built short production runs of JN-1, -2, and -3 variants, with the latter even seeing use in observation roles during the US Army’s 1916/17 invasion of Mexico, hunting for the revolutionary Pancho Villa whose forces had earlier raided a border town in New Mexico. It was the JN-4 which became the definitive version of the type, however, with the variant proving to be the most-widely produced aircraft in North America during period when the United States was involved in WWI. U.S. Army Air Service pilots first began calling the Curtiss JN-4 by its phonetically inspired nickname, ‘Jenny’, while Canadian examples of the breed became known as ‘Canucks’. JN-4s usually served in an unarmed training role, however some did receive modifications, such as bomb racks and machine guns, for advanced combat training purposes, while others underwent conversion into aerial ambulances.

After the war, thousands of surplus Jennys and Canucks, sometimes still packed inside factory shipping crates, ended up for sale on the civilian market. Indeed, the glut of ex-military Jennies (and their Curtiss OX-5 V8 engines) depressed demand for more expensive, new-build airframes from competing designers, withering some to the point of bankruptcy. The more daring pilots, sensing an economic opportunity, barnstormed their Jennies across the USA and gained fame for performing death-defying stunts in front of a crowd. They also provided untold numbers of Americans with their first glimpse of an airplane… or even their first ride aloft. It is arguable that many Allied pilots in WWII likely derived their inspiration to fly from those first encounters with a Jenny. The Jennies even helped map the first Postal Service routes which airlines would, in later years, adapt into their own pathways in the sky, some of which are still in use. The Curtiss Jenny though, despite its popularity back in the day, has not survived in large numbers, with just a handful of original airframes presently extant. Thankfully, the National Museum of the United States Air Force owns one of these survivors, and this will feature in today’s discussion.

The NMUSAF has virtually no details about their Jenny’s service life, but what they do know is that a man from Taylor, Texas named Robert Pfeil acquired the aircraft at an Army surplus sale in 1926. Pfeil often flew the aircraft on weekends, offering rides to locals, some of whom had never even seen an airplane before, let alone flown in one. At some point, Pfeil relocated his base of operations to Rich Field, a civilian airport in Waco, Texas which had once served the military in a training role during the Great War. Flying from Waco, Pfeil would barnstorm across Central Texas in 2805, selling rides wherever he went. By the mid-1930s, however, the Jenny’s allure was beginning to wane. The Great Depression was also still at mid-roar, which didn’t leave many Texans with sufficient disposable income to purchase a joy ride in a biplane. So, against this backdrop, Pfeil decided to park his beloved Jenny in 1936. It remained in his garage until 1956, when a man named John Clark learned from a television news feature that the United States Air Force Museum was looking to acquire a Curtiss Jenny for its collection in Dayton, Ohio. Clark relayed this information to Pfeil, knowing he still owned the Jenny. Interested, Pfeil contacted the museum’s purchasing agent and worked out a deal for the aircraft, which has been in their collection ever since.

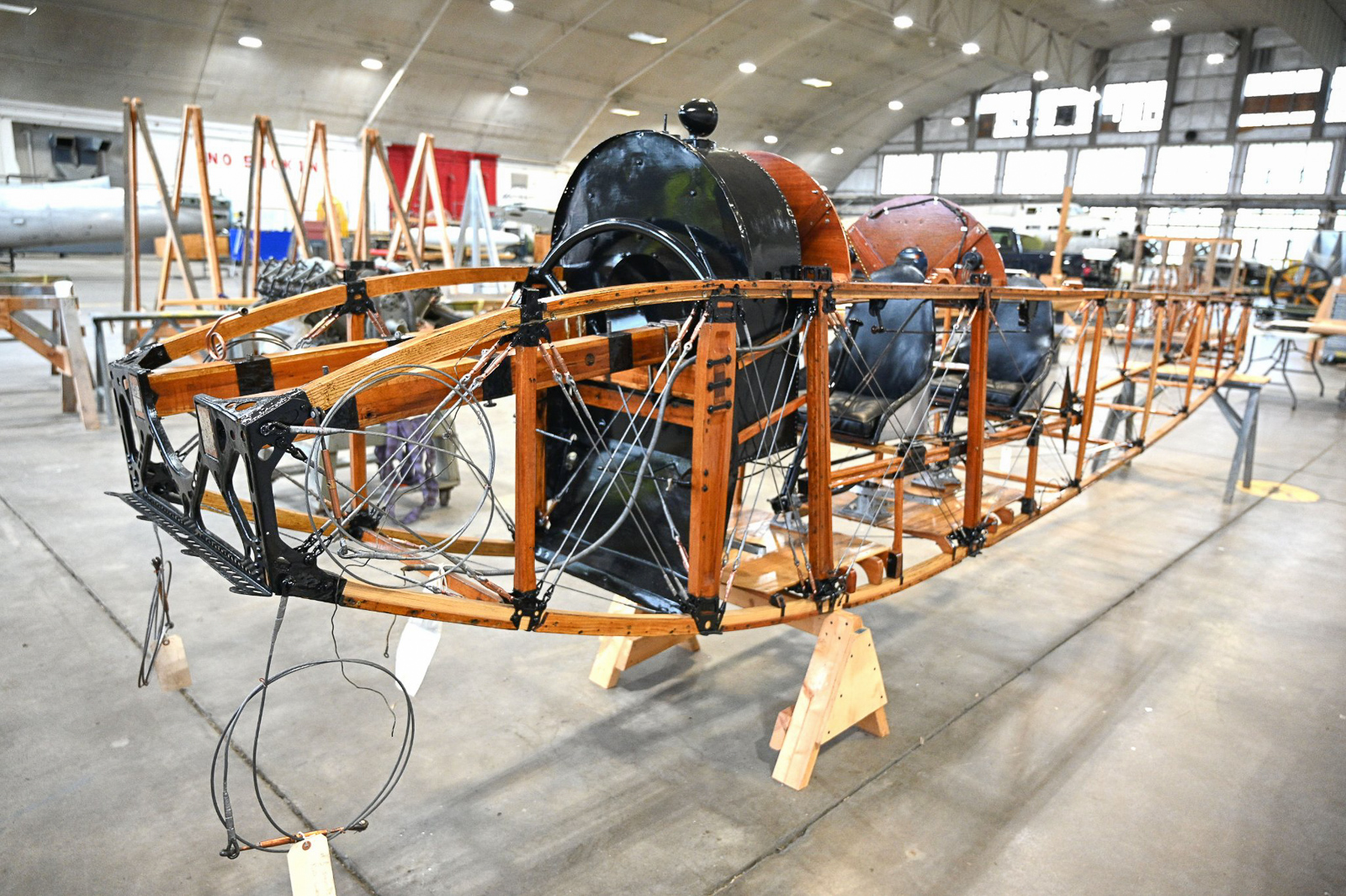

Fast-forward to the mid-2010s when the curatorial staff at NMUSAF realized that some of the aircraft in their Early Years Gallery needed refurbishing, starting with the Avro 504K replica. At around this time, the museum also lowered the Jenny and S4C Scout from the gallery ceiling, transferring them to their restoration facilities nearby within Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. While work on the Avro 504K reached completion in 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic obviously halted progress for some time on the other two airframes. Once it was safe to return to work, the museum focused their attention on finishing the Scout’s restoration first, since its condition was more demanding than was the JN-4’s. The Scout was ready for display in October 2021, so work then resumed on the Jenny. The conservation specialists carefully removed the old fabric to inspect the airframe. While some parts clearly needed replacing, much of the original structure was remarkably intact. The team has worked hard to retain as much original framework as possible and is clearly making great progress, as the accompanying images reveal. The images also make it clear that authenticity is a high priority for museum personnel as well. The restoration team is confident that the Jenny will be completed and returned to the Early Years Gallery sometime in the near future.

Other restoration team members are also hard at work putting the finishing touches on their Douglas A-1H Skyraider which was the subject of my earlier article.

For more information on the National Museum of the United States Air Force, please check out their website here: https://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/

The author also wishes to express his gratitude to the museum for providing him with photographs and information about their Curtiss JN-4D Jenny.

There is a nice photo of the panel here:

https://catalog.archives.gov/search-within/530707?availableOnline=true&page=91

Correct link:

https://catalog.archives.gov/id/55162305