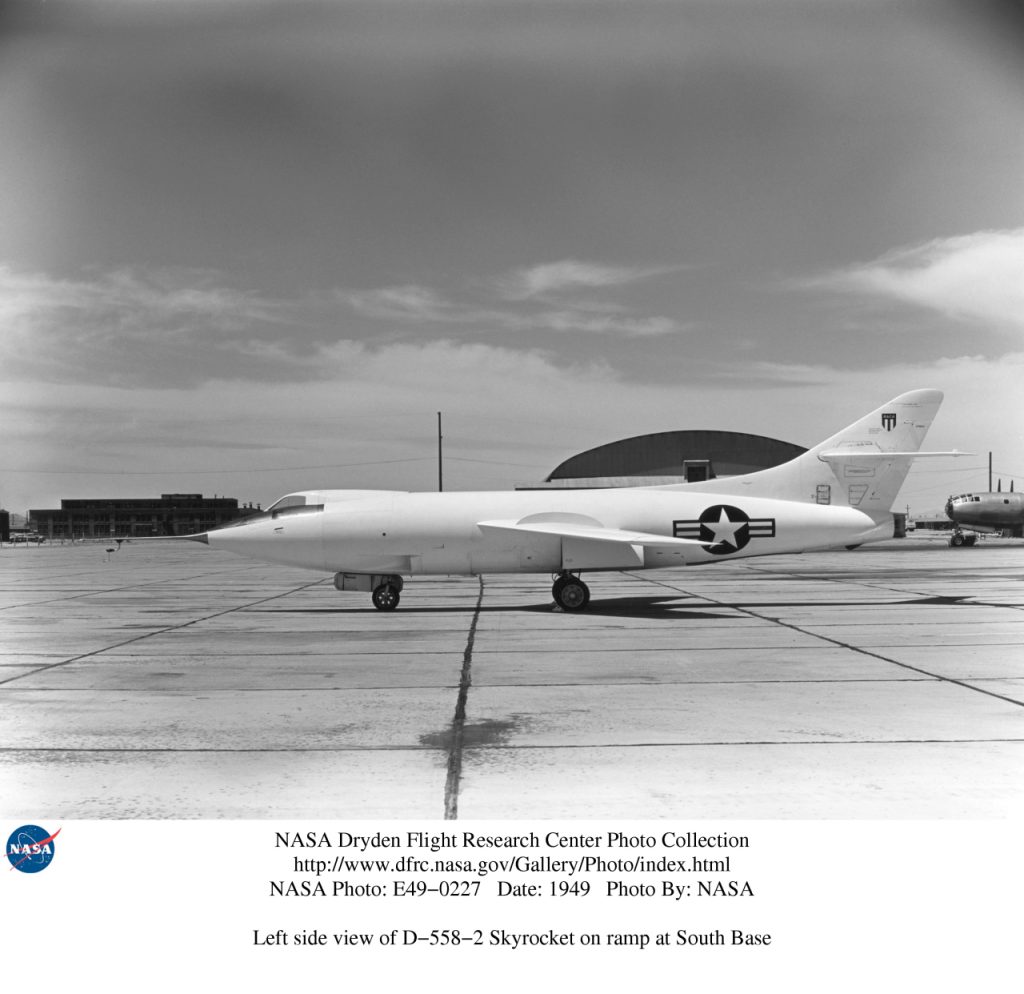

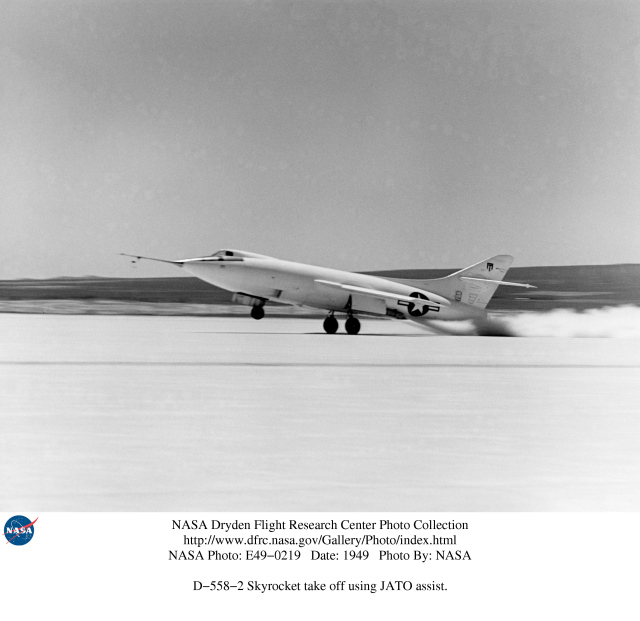

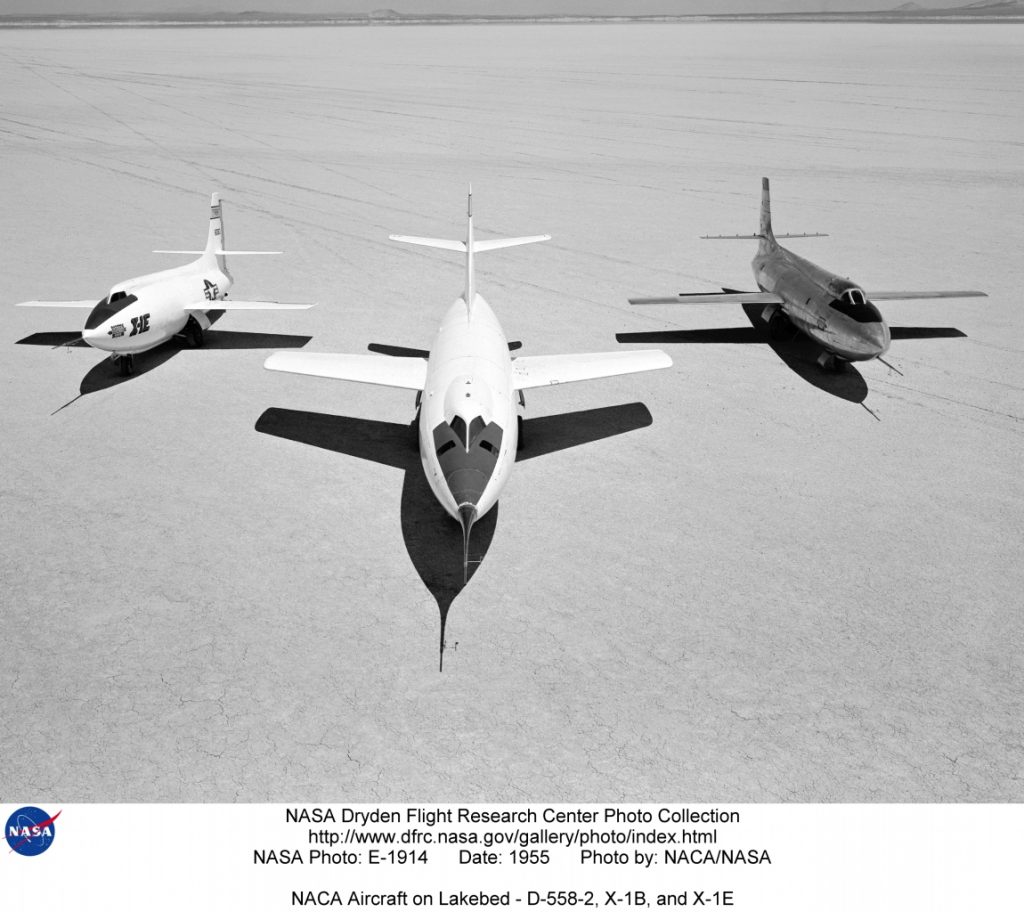

Today, we take a closer look at the Douglas D-558-2 “Skyrocket,” one of the pioneering aircraft of the transonic era, flying alongside the likes of the X-1, X-4, X-5, and XF-92A. Developed as a joint program between NACA, the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, and the Douglas Aircraft Company, the swept-wing, single-seat Skyrocket flew from 1948 to 1956 with the goal of solving high-speed flight challenges—particularly the dangerous “pitch-up” phenomenon.

Three Aircraft, One Mission

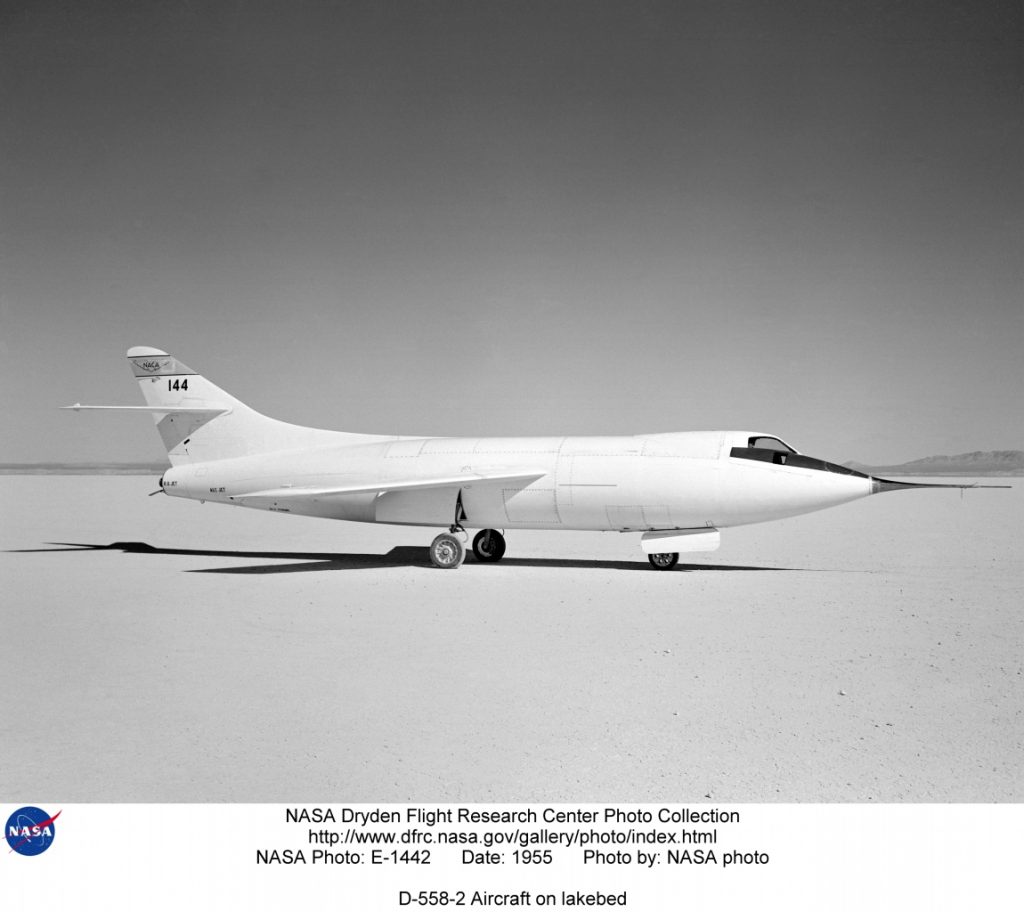

Three Skyrockets were built, designated Bureau Numbers 37973, 37974, and 37975—NACA 143, 144, and 145, respectively. They flew a total of 313 missions, collecting invaluable data on pitch stability, lift, drag, and buffeting in transonic and supersonic flight. The first Skyrocket, NACA 143, began with a turbojet engine, later modified to an all-rocket configuration. After this conversion, it was launched from a Navy P2B (a modified B-29) at altitude. Research pilot John McKay flew it once in this form on September 17, 1956. The jet- and rocket-powered aircraft exceeded expectations, performing better than predicted in high-speed wind tunnel tests—particularly in drag performance above Mach 0.85.

Skyrocket 144: Climbing to the Edge

NACA 144 followed a similar evolution, beginning with a turbojet engine before being outfitted with a powerful LR-8 rocket. Piloted by William B. Bridgeman, it achieved Mach 1.88 and reached an altitude of 79,494 feet on August 15, 1951—an unofficial world record at the time. Subsequent flights by NACA pilots, including A. Scott Crossfield, focused on understanding the aircraft’s behavior in all axes of motion. Crossfield flew the Skyrocket 20 times, collecting critical data on longitudinal and lateral stability. In 1953, U.S. Marine Lt. Col. Marion Carl flew the same aircraft to another record-breaking altitude of 83,235 feet and a top speed of Mach 1.728.

1949

NACA engineers improved the rocket’s performance by adding nozzle extensions to its combustion chambers, reducing exhaust interference with the rudders and increasing thrust at altitude. They also chilled the alcohol fuel and waxed the aircraft’s fuselage to reduce drag for a record attempt.

Breaking Barriers: Mach 2

That record attempt came on November 20, 1953. Scott Crossfield, in a daring flight plan devised by project engineer Herman Ankenbruck, pushed the Skyrocket to its absolute limits. Dropped from a P2B at 32,000 feet, he climbed to over 70,000 feet, then nosed into a gentle dive. The aircraft reached Mach 2.005—1,291 mph—making Crossfield the first pilot to fly at twice the speed of sound. This flight marked the pinnacle of the Skyrocket’s career and underscored NACA’s growing role not just in research, but in making history.

NACA 145: Tackling Pitch-Up and External Loads

The third aircraft, NACA 145, was used extensively to investigate “pitch-up”—an uncommanded nose rise encountered at high angles of attack, particularly dangerous in swept-wing aircraft. Pilots Scott Crossfield and Walter Jones flew with different wing configurations, including fences, slats, and extended leading-edge chords. Their work proved wing fences were effective in reducing pitch-up, while leading-edge chord extensions were not—contradicting prior wind tunnel findings. Later, Crossfield and other NACA pilots, including John McKay and Stanley Butchart, conducted tests with external stores—bomb shapes and fuel tanks—to evaluate their influence on flight behavior near Mach 1. The final Skyrocket mission took place on August 28, 1956.

Legacy of the Skyrocket

Beyond the records, the Douglas D-558-2 Skyrocket played a key role in improving the understanding of high-speed flight. Its test flights provided data that shaped the designs of later swept-wing military aircraft, including the Century Series of jet fighters. The Skyrocket also contributed to refining wind tunnel methodologies and validating theories of flight dynamics in the transonic and supersonic regimes.

The Skyrocket’s influence extended to control system designs as well—its data supported the adoption of all-moving horizontal stabilizers, which became standard on high-speed aircraft following the X-1 and D-558 series. In short, the Skyrocket wasn’t just a record-setter—it was a knowledge generator, providing the foundation for future aircraft that would fly higher, faster, and more safely than ever before. Read the entire Flight Test Files article, click HERE.

I was fascinated to read Bill Bridgmans book The Lonely Sky describing the development of the Dougless Skyrocket