Wiley Hardeman Post first saw an aircraft, a Curtiss-Wright Pusher, in 1913, in Lawton, Oklahoma. Though he was only 15 years old, post enrolled in the Sweeney Automobile and Aviation School in Kansas City. Soon after he returned to Oklahoma, World War I began, and Post wanted to join the U.S. Army Air Service (USAS) as a pilot. The war ended before he could accomplish that desire, so Post went to work in the Oklahoma oilfields. The work was unsteady, and he turned briefly to a life of crime, which landed him behind bars for a time.

In 1924, while continuing work in the oilfields, Post’s aviation career finally began when he joined Burrell Tibbs and His Texas Topnotch Fliers, as a parachutist. On October 1, 1926, Post was badly injured in an oil-rig accident, which ultimately caused him to lose his vision in his left eye. From then on, Post was most often seen with his famous eyepatch. It was around that time, Post met fellow Oklahoman Will Rogers.

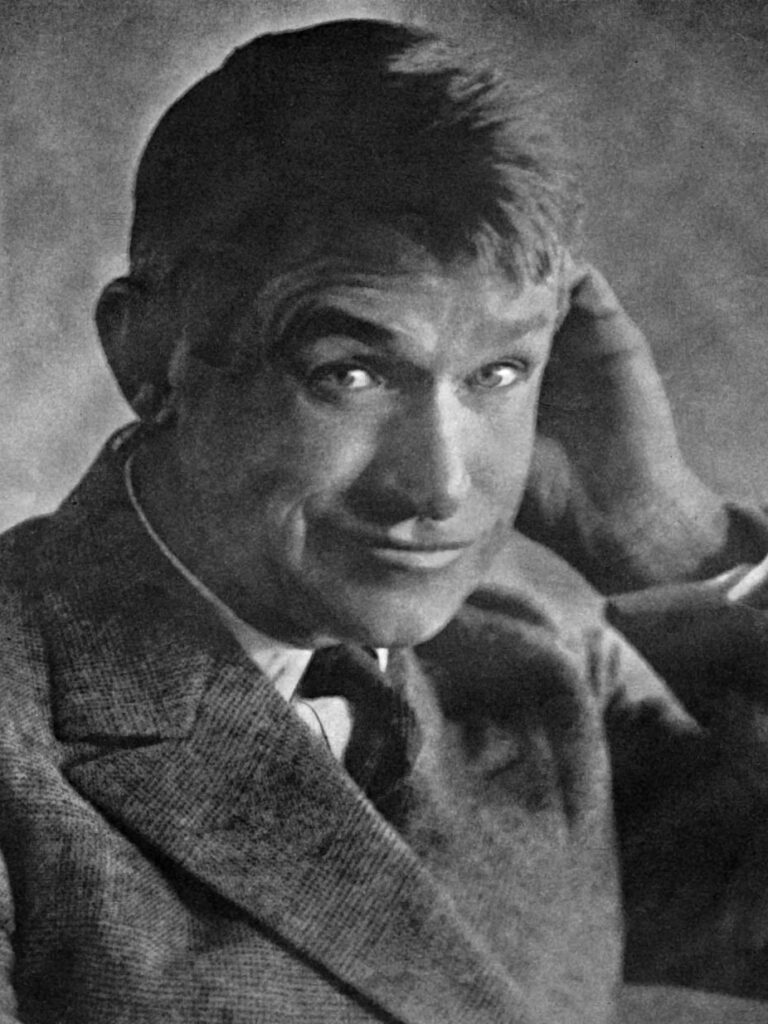

William Penn Adair Rogers was an American vaudeville performer, actor, and humorous social commentator. Rogers wasn’t just a native of Oklahoma, he was a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and is known as “Oklahoma’s Favorite Son”. During his life, Rogers traveled around the world three times, made 71 films and wrote more than 4,000 nationally syndicated newspaper columns. By the time duo began their fateful flight in 1935, Rogers was hugely popular in the United States for his leading political wit and was the highest paid of Hollywood film stars, while Post set numerous record flights, including becoming the first pilot to fly solo around the world, was had begun working on high altitude pressure suits.

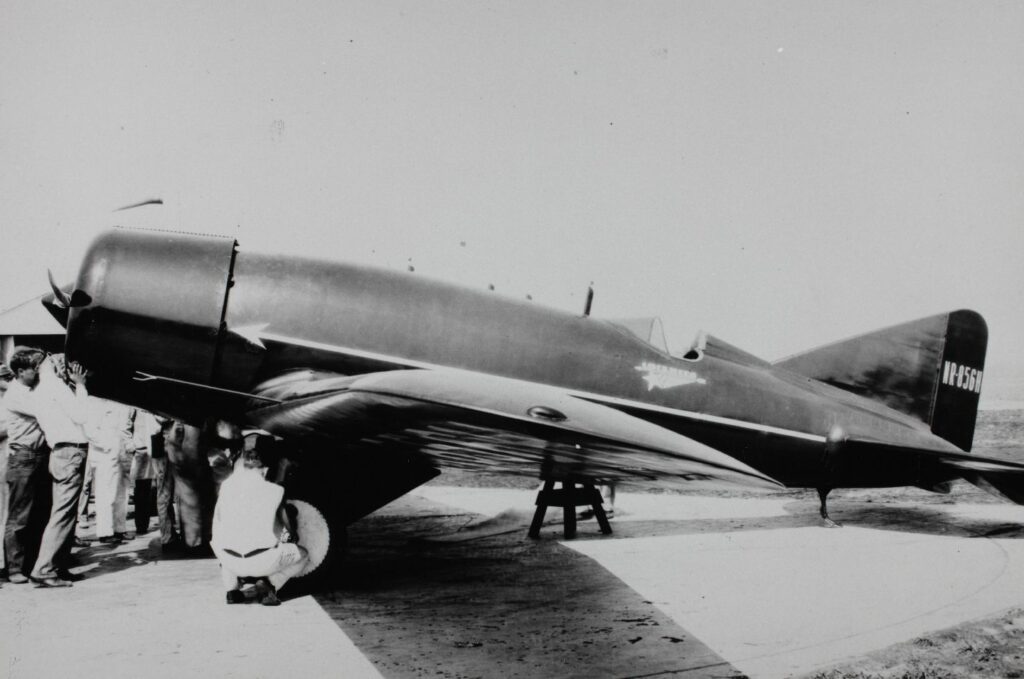

In 1935, Post became interested in surveying a mail-and-passenger air route from the West Coast of the United States to Russia. Short on cash, Post built a hybrid aircraft using the fuselage of a Lockheed Orion and the wing of a wrecked Explorer 7. The aircraft, referred to as the Orion Explorer was powered by a 600hp Pratt & Whitney Wasp S3H1 radial, and nicknamed Wiley’s Bastard and Aurora. When it was completed, the aircraft used the registration, NR12283, which has been assigned to the Orion.

While Post’s Explorer-Orion was being built at Pacific Airmotive, Will Rogers visited him several times and on one of those visits he asked Post to fly him to Alaska in search of new material for his newspaper column. When the floats Post had ordered were delayed, he used a set designed for a larger aircraft, which reportedly made the hybrid Lockheed quite nose heavy.

After making a test flight in July, Post and Rogers left Lake Washington, near Seattle, in early August and made several stops in Alaska. During the long flights, Rogers wrote his columns on his typewriter. On August 15, they left Fairbanks, Alaska, for Point Barrow. What follows is an eyewitness account (verbatim) that was related to Staff Sergeant Stanley Morgan, who was in charge of a remote Army radio station and appeared in the Saturday August 17, 1935, edition of the Oakland Tribune, “At 10 p.m., last night (Thursday), attracted by groups of excited natives on beach. Walking down, discovered one native all out of breath gasping in pidgin English a strange tale of ‘airplane she blew up.’

After repeated questioning this native witnessed crash of an airplane at his sealing camp some 15 miles south of Barrow and had run the entire distance to summon aid:

Native claimed plane flying very low suddenly appeared from the south apparently sighting tents. Plane then circled several times and finally settled down on small river near camp, two men climbed out, one wearing ‘rag on sore eye’ and other ‘big man with boots.’

The big man then called native to water’s edge and asked direction and distance to Point Barrow. Direction given, men then climbed back into plane and taxied off to far side of river for take-off into wind.

After a short run plane slowly lifted from water to height about 50 feet banking slightly to right when evidently motor stalled. Plane slipped off on right wing and nosed down into water, turning completely over and native claimed dull explosing occurred and most of right wing dropped off and a film of gasoline and oil soon covered the water.

Native frightened by explosion turned and ran but son controlled fright and returned. Calling loudly to men in plane. Receiving no answer native then made decision to come to Barrow for help.”

When the native finished the story SSgt Morgan, knew the plane that crashed was that of Wiley Post and Will Rogers and he quickly gathered 14 Eskimos and started towards the crash site in an open whale boat. Though only 15 miles away, it took three hours to reach the site because the boat was hampered by ice floes. By the time they reached the aircraft, a group of natives had managed to remove Rogers’ body, but it was it took much longer to extricate Post because he was pinned in the cockpit by the engine.

The bodies were placed in sleeping bags that were found in the wreckage. Morgan related that the natives must have felt the weight of the loss of the two great men. The article read, “…our slow trip back to Barrow one of the Eskimo boys began to sing a hymn in Eskimo and soon all of the voices whined in this singing and continued until our arrival at Barrow, when we silently bore the bodies from the beach to the hospital…”

The accident, which sounds like a typical low-altitude stall/spin, has been studied over the decades and many claim the larger than planned floats made the aircraft nose heavy. In 2001 however, Bryan and Frances Sterling published Forgotten Eagle: Wiley Post: America’s Heroic Aviation Pioneer wrote that the floats fitted to the Explorer-Orion were correct, thus suggesting another cause for the crash. Like so many aviation accidents throughout history, we will never quite know for sure.

The bodies of the beloved Oklahomans were flown back to the lower 48 a few days after the accident. Rogers was temporarily buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California on August 21 and re-interred at the Will Rogers Memorial in Claremore, Oklahoma in 1944. Wiley Post was also buried in Oklahoma in Memorial Park Cemetery in Oklahoma City.

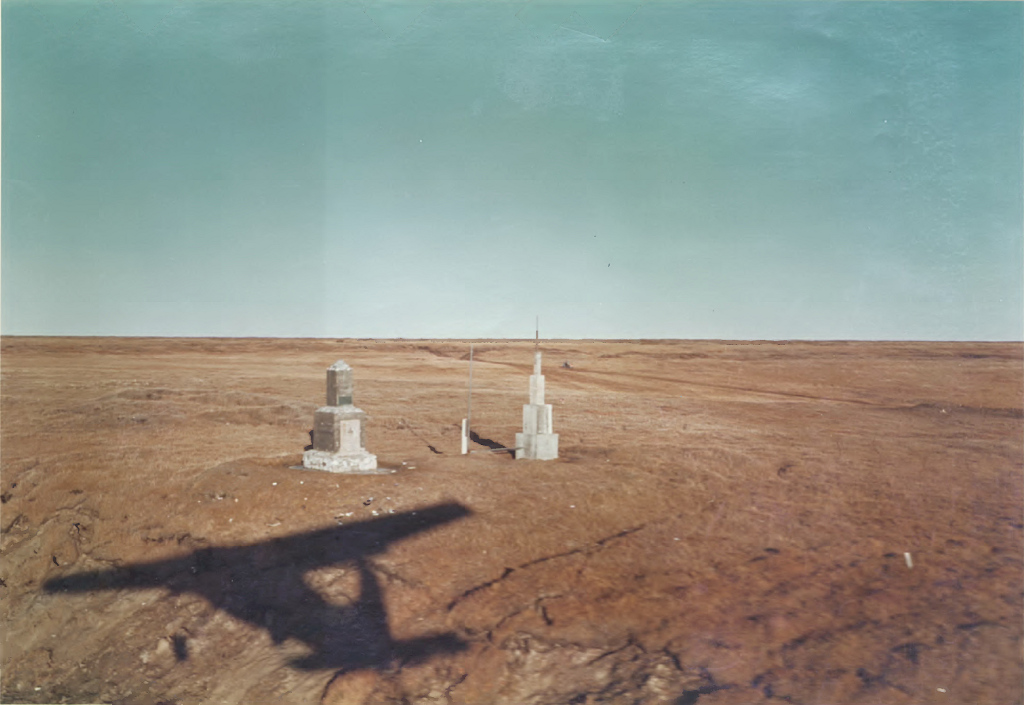

Up in Point Barrow, a pair of monuments were erected at the crash site to memorialize the pair and has been listed on National Register of Historic Places and the airport located at nearby Utqiagvik, Alaska was re-named Wiley Post-Will Rogers Memorial Airport.