It has been about a year since we reported on the major revelation that many thousand original North American Aviation manufacturing drawings survived destruction during the 1980s because one of their employees, Ken Jungeberg, saved them from incineration. Furthermore, as we also discussed last year, AirCorps Aviation worked out a deal with Jungeberg in 2019 to secure these historic artifacts for their longterm preservation. Ever since their arrival at AirCorps last winter, Ester Aube, the company’s manager for their technical documentation division, AirCorps Library, has been working diligently to preserve and catalogue this massive archive. With so many drawings to review, this would be a daunting task for anyone to undertake successfully, but Ester has applied her keen intellect, professional training and substantial skillset to systematically document and collate these drawings into a practical and valuable resource for aircraft restorers, historians, and the aviation-minded public at large. Additionally, Aube has delved deeper into the process, tracing personal details for several NAA technicians who originally drafted these drawings, because their stories are no less important to the narrative than the documents themselves; this aspect of aviation history has received little prior attention from the wider world …until now.

This mammoth endeavor is still ongoing, of course, but Ester Aube has made excellent progress, so we asked her to talk a little about what her work has involved so far. We feel sure that our readers will be fascinated by what she has discovered…

Process Continues on Trove of Original NAA drawings at AirCorps Aviation

by Ester Aube (Manager of AirCorps Library)

In 1988 Ken Jungeberg, head of the Master Dimensions Department at North American-Rockwell’s Columbus plant, was given permission to take a large number of non-current drawings from the company archive. These drawings were slated to be incinerated, but Ken understood their value, and his many letters to company officials along with a burst water pipe, came together to assure that this trove of historical information was saved. As an avid WWII aviation enthusiast, Ken spent the next 31 years storing the drawings in his basement and small hangar while sifting through them in his spare time. (Click here to read more about Ken’s story.)

It has been a little more than a year since AirCorps Aviation acquired this collection of original North American drawings from Ken, and a lot has happened in that time. When the crates and boxes were unloaded into the newly named AirCorps Archives facility in Bemidji, Minnesota, the building seemed spacious. However, as 2020 went on and I began to unpack and sort through the drawings, I began to feel more and more like a hoarder, walking on tiny paths through a house stacked with old paper. Most who visited the Archives at that time said the same thing: “I could never do what you’re doing!”

Before I could even begin sorting the drawings, I knew I needed a plan. Ken had initially estimated that there were around 8,000 total drawings in his collection, but I had a sneaking suspicion that there were more (my initial estimate was 15,000). With drawing quantities in the thousands, diving into the project at random was not an option. Fortunately, North American’s part numbering system came to the rescue.

I discuss many different part numbering systems on a regular basis with members of our AirCorps Library site, but I always end up thinking that North American “did it right”. Their part numbering system was so detailed and intuitive that using it as the structure for organizing Ken’s drawings simply made sense. Additionally, I was wary of creating a system from scratch that might only seem logical to me, and I also didn’t want similar items to be spread out in different locations. Using NAA’s existing system meant that future researchers and enthusiasts would be able to find what they were looking for quickly and easily, because they would have a common frame of reference to work from – the part numbers.

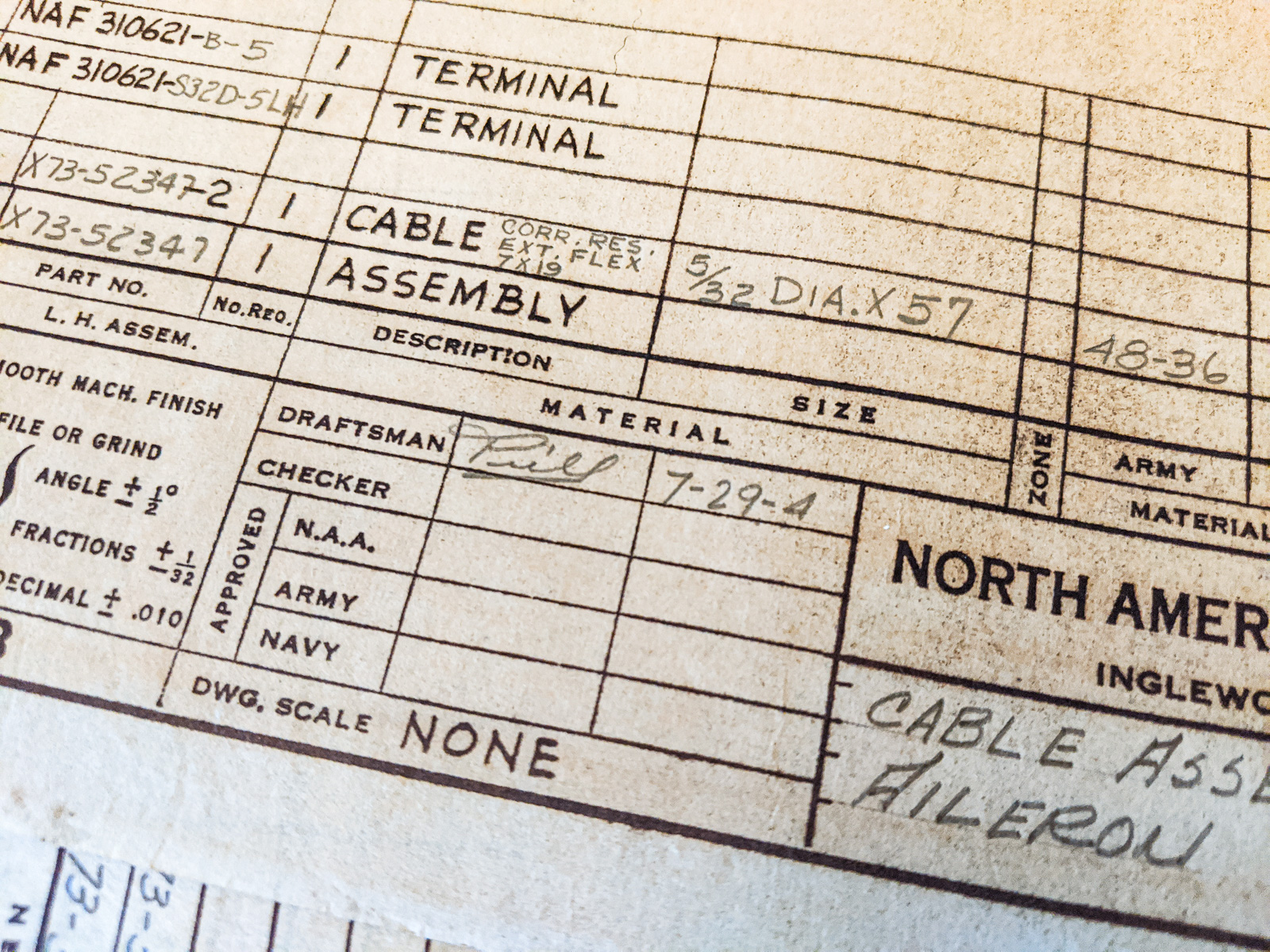

The standard NAA part number begins with two or three digits, followed by a hyphen and then five to six additional digits (Example: 108-00044). The first set of digits, or prefix, is a designation for the specific model of aircraft that the part was initially designed for. The “108-” in our example above indicates that this drawing would have originally been drawn for a B-25J. While parts were often used on later models of the same aircraft, or interchangeable between different aircraft, the prefix always indicates its original applicability. A photocopy of an original document in Ken’s collection detailed almost 200 different NAA prefixes. After retyping this document and turning it into a series of posters, I had the framework to begin organizing the drawings.

|

PREFIX |

MODEL |

|

36- |

BC-1 |

|

52- |

SNJ-1 |

|

82- |

B-25C |

|

97- |

A-36 |

|

144- |

F-82E |

Several examples of NAA prefixes and the respective model of aircraft they represent.

As I began to unpack box after box, I paged through each individual drawing and sorted those with like prefixes into piles. Initially I had planned to group prefixes that I knew I would have a lot of drawings for together into one room in the archive, but it quickly became obvious that would be impractical. After only a few weeks of unpacking, I had piles for almost 100 different prefixes, so I decided to completely reorganize them such that these piles were in numerical order. At this point I had drawings from prefix “16-” for the NA-16 (the early predecessor of the T-6) dated in the mid-1930s, to prefix “192-” for the F-100A Super Sabre, and everything in between.

In February 2020, we unveiled several examples from Ken’s collection at the National Warbird Operators Conference (NWOC) in Mobile, Alabama and received rave reviews. Attendees pored over the drawings, some of which had never been seen before by anyone outside of NAA. After NWOC, I went back into the Archives with a new sense of purpose. It was clear that the warbird community was just as excited about seeing Ken’s collection as we were at AirCorps. As the sorting continued and the stacks of drawings got larger and larger, I knew that I had to start thinking about the next step in the organizing process.

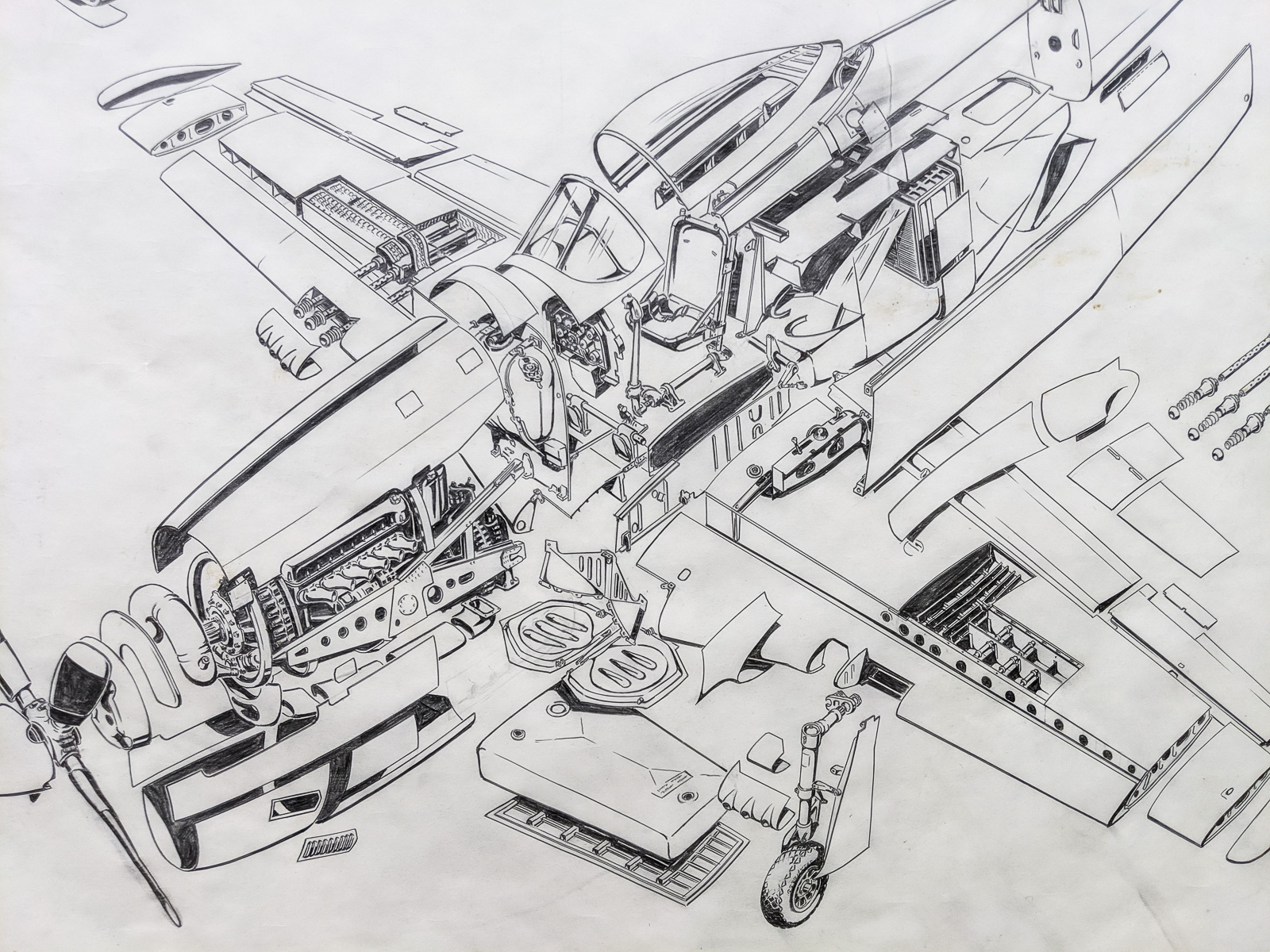

By August 2020, I had finally finished sorting every drawing in Ken’s collection by its prefix. At that point, almost every square inch of the 3,000 square foot Archive building was covered with drawings; in order for me to continue, I needed to create a space to work. To keep things organized, I knew I had to focus on one aircraft at a time. Given that our main body of work at AirCorps has involved the P-51 Mustang, plus the strong interest for that type in the warbird community, it made the most sense to start with that aircraft. North American created 15 separate prefixes referring to the P-51, so in order to get a clear view of what we had, I packed away everything unrelated to those numbers for later review.

With those other drawings safely stowed, I now had room to sort each of the P-51 prefixes by drawing size. North America used five standard drawing sizes during WWII, and each of them had a letter distinction. NAA referred to these five standard sizes as “cut size” drawings, while they labeled larger drawings by “roll size.” If you are familiar with looking at drawings on microfilm, you have undoubtedly noticed that the letter indicating the drawing size is always listed on a NAA drawing, but without seeing the original drawing and how large or small it is, it’s hard to get any meaning out of these letters.

|

Drawing Size Distinction |

Actual Size (inches) |

|

A |

8½ x 11 |

|

B |

11 x 17 |

| C |

11 x 34 |

| D |

16¾ x 22 |

| G |

21¾ x 33½ |

Once each of the fifteen different Mustang prefixes was sorted into the five individual piles by their cut size, the next step of the process could begin – putting each pile in numerical order. As may be imagined, this step of numerically ordering drawings was the most time consuming to date. Having piles sequentially organized meant that, for the first time, I could find a drawing that someone might be looking for relatively quickly, rather than sifting through a pile of drawings at random!

From the first day we acquired the drawings, I had been thinking about the best way to catalog the collection. I was familiar with a handful of museum database systems, but knew that none of them were customizable to the data that I was interested in entering for Ken’s collection, plus the startup costs were incredibly high. Most museum software is fairly standardized and has predetermined fields for items like location, condition, provenance, owner, and many more. While these were all items that I wanted to capture for each drawing, there were other fields that were much more specific to this collection, such as the draftsman, checker, date drawn, drawing description, factory, revision letter, next assembly, and model applicability, just to name a few. Fortunately, I was able to find the perfect cost-effective program that made customizing our database easy.

Once I finished setting up the new database program, and having organized the drawings numerically, I was able to start giving each drawing a location and entering basic information for each of them into the system. After numerically ordering all the drawings of a single size for a specific prefix, I entered four details: the part number, location, draftsman, and drawing size for each drawing into the cataloging program. In order to move quickly without getting bogged down, I decided to only catalog these four fields. Once I had done this for every Mustang drawing, I would go back to the beginning and start entering more detailed information about each of them.

Beyond feeling like things were finally coming together as I entered information into the initial fields, I also started to get an idea of the total number of drawings in the collection. Up until this point, my estimate of 15,000 total drawings was just that, an estimate. As the number of drawings continued to grow, it became clear that my initial 15,000 estimate was low – very low. Currently, I have cataloged 14,949 total drawings, and 13,917 of these are specifically for the P-51! With the quantity of drawings I know we have for the B-25, I believe the total drawing count will be well over 30,000 by the time I finish cataloging the Mitchell!

As of January 2021, I have finished the initial cataloging of the cut size drawing for the Mustang, but the numbers will continue to rise as I move into cataloging the larger roll size drawings for the P-51, which I have yet to start doing.

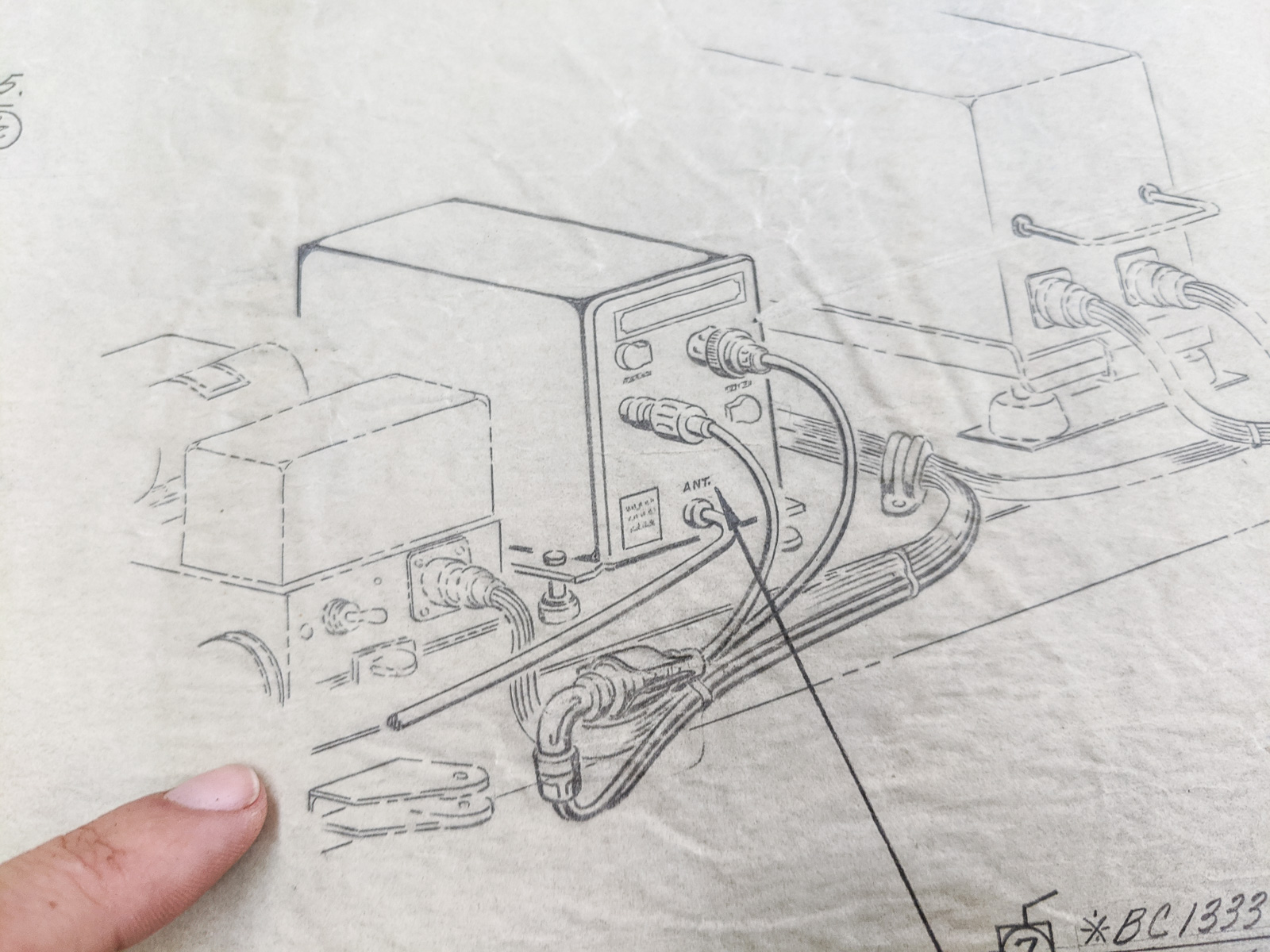

Now that the initial phase of cataloging is complete for the Mustang, I am able to start a deeper dive into the specific details of each drawing. Because many of the drawings in Ken’s collection were experimental or non-production, simply cataloging the part number did not provide enough information. These experimental drawings are not listed in Parts Catalogs or microfilm indices, so entering the full drawing description is key to fully understanding what each drawing relates to.

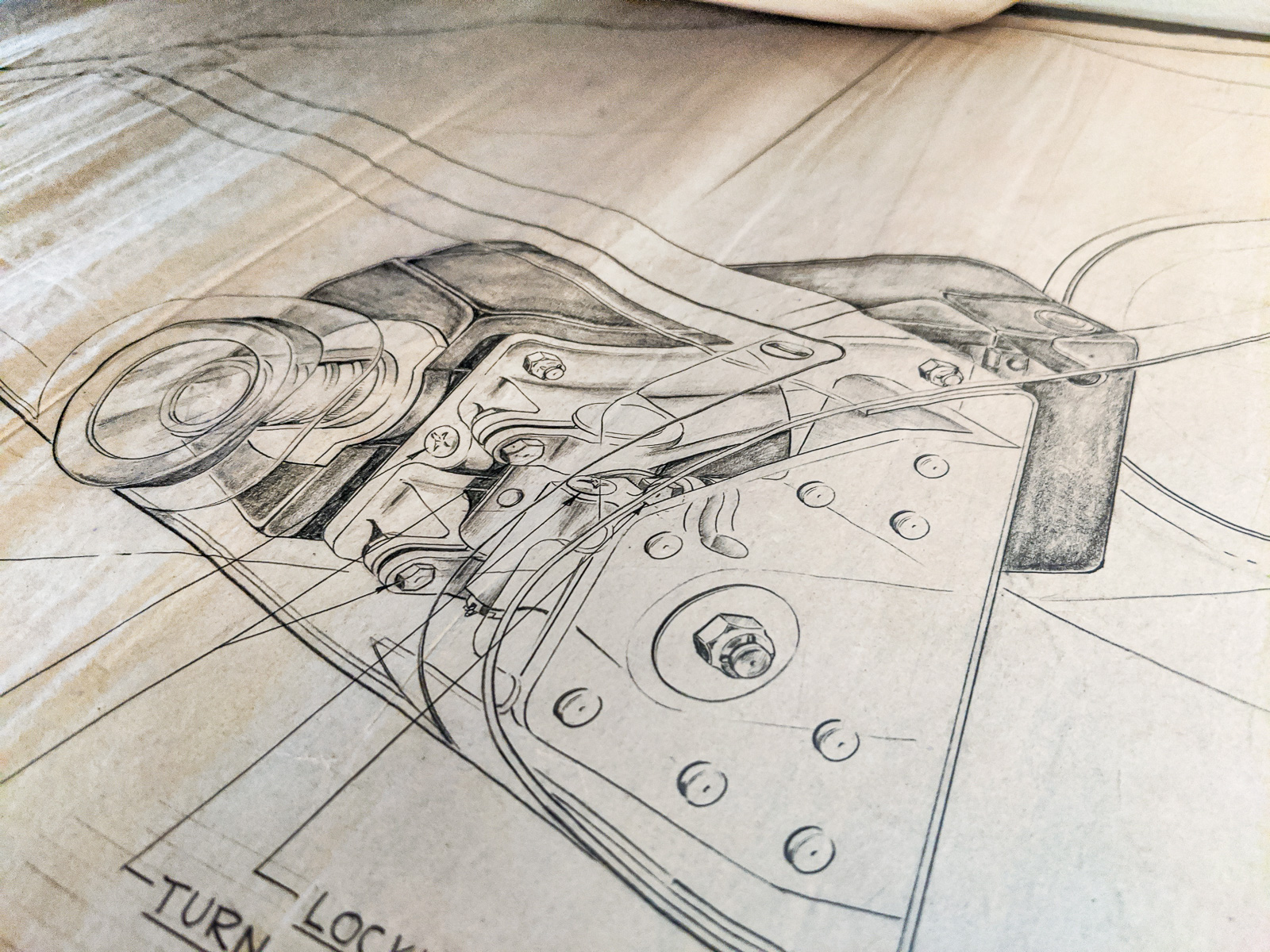

For me, one of the most interesting fields on each drawing has been the box identifying who actually drew it up. Entering their names into our database, and seeing the differences in the way they signed drawings, gives me a keen sense of connection to their work. Many draftsmen signed their last name using the same standardized, all-capitals script (similar to our modern Gill Sans font) which they used to write information on a drawing, both in the title block and on the main drawing. However, occasionally you find someone using a different signature, someone like Fred Prill.

Fred was part of the initial team chosen to perform design work on the NA-73X, the first prototype of what would later become the P-51. He went on to become the lead engineer for the F-86, which would remain his favorite aircraft for the rest of his life. Currently, I have cataloged 78 of Fred’s drawings, including a group of 16 which are all related to the X73 aileron and rudder parts and assemblies (drawn from June to July of 1940). Several months ago, I had the opportunity to speak with Fred’s son Bob, and he regaled me with stories about his father and remembered Lee Atwood visiting their home for dinner on multiple occasions. Other stories included Bob’s time playing baseball at NAA’s “Baseball School” at the Inglewood rec center, and his first flight experience, at 12 years old, riding along with Fred during a T-39 Sabreliner test flight! Bob described his father as being “married to North American” as he recounted his father’s stories of sleeping on a cot at the factory while working on the NA-73X, but importantly, he did qualify this by saying that his father “never made my mother feel second best.”

Connecting the drawings in Ken’s collection to the human stories surrounding the people, like Fred, who drew them, is what will make Ken’s collection come to life. As the years go by, and we are left with fewer and fewer individuals who can remember the war years, it is more important than ever to catalog their stories by whatever means are available. While Fred Prill passed in 2003, I still feel I got the chance to know him a little through his son, and getting to handle the drawings pencilled by his own hand is a very humbling experience.

I would love the opportunity to connect with anyone else who has/had relatives who worked in the Inglewood drafting department during WWII. The stories from those days are so important to preserve for future generations, and connecting a family to the drawings their relatives created is very rewarding. The technicians who drafted these drawings so often get overshadowed by the pilots and other enlisted men and women who served, but without their engineering prowess and raw artistic talent, America would never have been able to accomplish what it did during the war. I would like to do my part to say thank you to them and to ensure that their contributions are valued and remembered more fully. Please feel free to contact me at [email protected] or 218-444-4478 if you have any information which may help me locate family members of these important technical artists.

Many thanks indeed to Ester Aube for this update on what must be a fascinating task. Her work is invaluable to the preservation and widespread understanding of the greater story of aircraft production during WWII. Furthermore, AirCorps Library is an invaluable resource for anyone interested in how those magnificent aircraft went together, and well worth the $60 annual subscription fee.

Related Articles

Richard Mallory Allnutt's aviation passion ignited at the 1974 Farnborough Airshow. Raised in 1970s Britain, he was immersed in WWII aviation lore. Moving to Washington DC, he frequented the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum, meeting aviation legends.

After grad school, Richard worked for Lockheed-Martin but stayed devoted to aviation, volunteering at museums and honing his photography skills. In 2013, he became the founding editor of Warbirds News, now Vintage Aviation News. With around 800 articles written, he focuses on supporting grassroots aviation groups.

Richard values the connections made in the aviation community and is proud to help grow Vintage Aviation News.