Advertorial*

By Stephen Chapis

In 1944, having built more than 30,000 military aircraft and the end of the war just starting to crest the horizon, Grumman was looking to enter the civilian market that was sure to be flooded with DC-3s, DC-4s, and other military transports that could be readily converted to airliners. Remembering how the Goose came to be because of wealthy “sportsmen” who wanted a fast and comfortable amphibian for commuting between their jobs in New York City to their fishing lodges, Grumman revisited this concept.

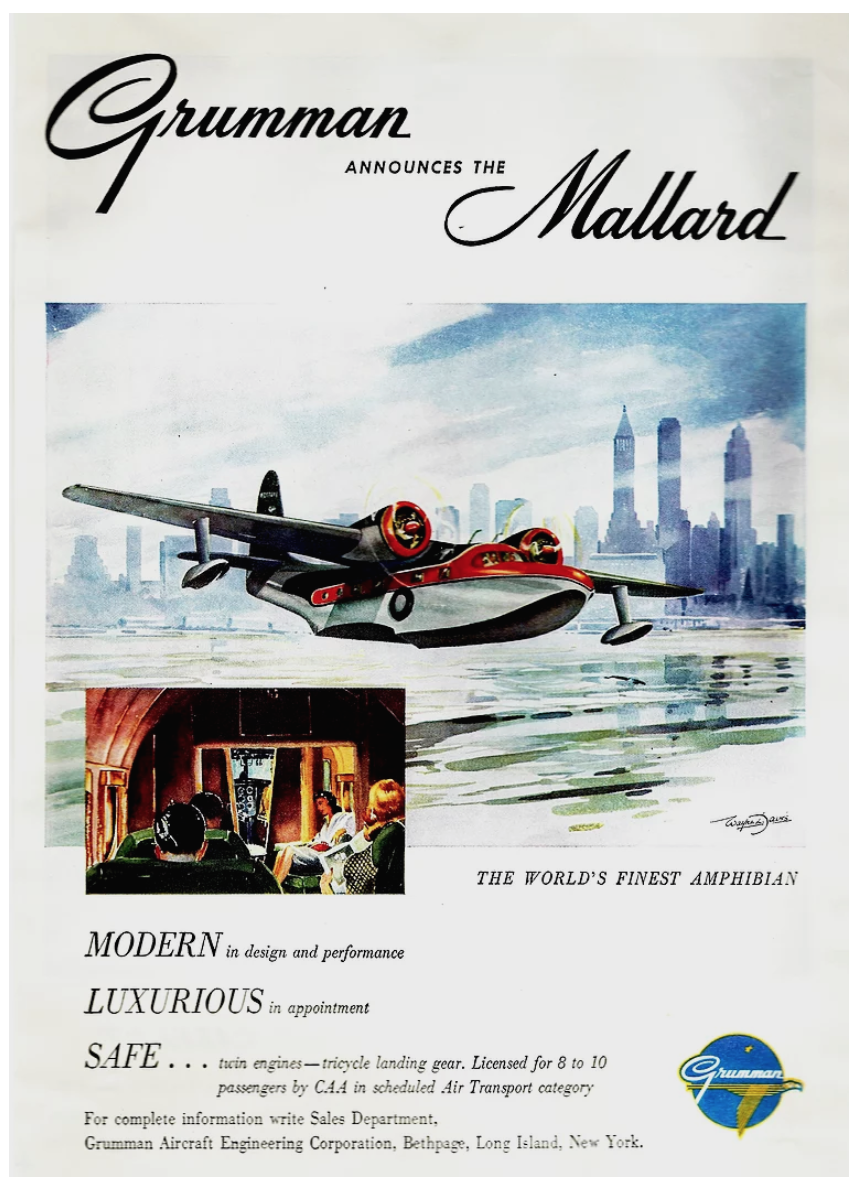

A little older and a lot wealthier, their call was for a safer, bigger, more comfortable and faster amphibian. Project leader Gordon Israel scaled down the advanced hydrodynamic hull of the Albatross, equipped it with a luxurious cabin for ten and designed a gracious, transport category executive transport. Grumman literature from the period described the Mallard as “fast and sleek” and offered such features as, “richly appointed interior, high performance, and exceptional utility.” Grumman proudly named the Mallard, “The World’s Finest Amphibian.” Read the company official brochure: Announcing the Mallard

On September 27, the first production aircraft (c/n J-2, CF-BKE), was delivered to McIntyre Porcupine Mines in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Over the next five years, Grumman sold an additional fifty-six Mallards to private individuals and corporate leaders such as Henry Ford and Bill Boeing in the United States, Canada, Great Britain, and two to the Egyptian Air Force for use by King Farouk.

When Mallards were followed by Grumman’s turboprop Gulfstream, many were stripped of their executive interiors, fitted with turboprops and repurposed as ocean commuters to fly heavy loads to and from open ocean conditions. Within ten years most were destroyed by salt-water corrosion that weakened structural components that were then easily cracked by landing and take-off conditions that far exceeded Grumman’s design limits. When the cost of rebuilding a corroded Mallards’ center section reached a million dollars and more, many were scrapped…”

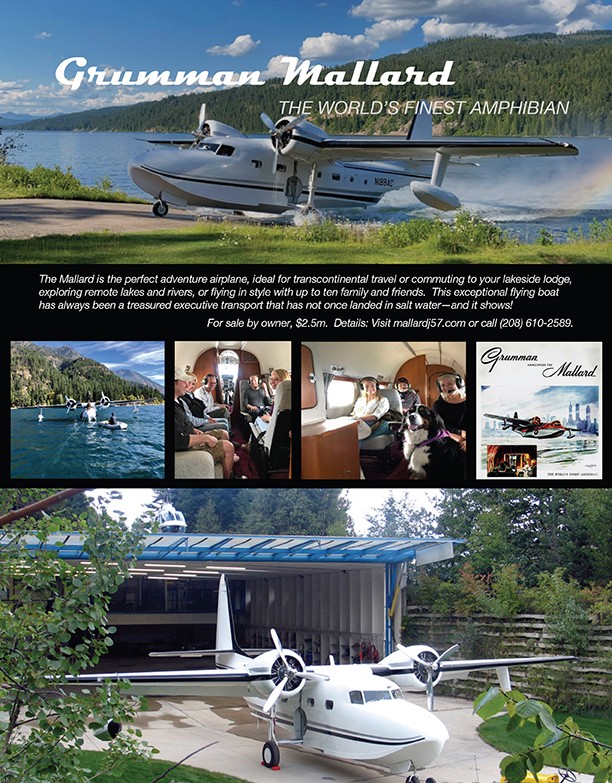

For quite some time there were only two Mallards that were known to have avoided saltwater operations, and thus retained their condition and value. When Loel Fenwick, the owner of the Mallard seen here, discovered a third pristine Mallard, he bought it to keep it from going to sea.

Loel Fenwick told Warbird Digest how he caught the flying bug, “Farmer friends in Zululand taught me the basics, the University of Cape Town Flying Club gave me wings and systems, and I learned most from an instructor who let me take turns flying a Piper Seneca ambulance. I flew the empty leg while he instructed. He flew back while I attended to the patient.

However, the story of how Fenwick gained an affinity for flying boats reads like something straight out of Indiana Jones. Fenwick explained, “My first [seaplane] flight was with my mother and thirty other passengers aboard a BOAC Short Solent Empire Class flying boat. It was five-day trip from Southampton, England to Johannesburg, South Africa. Each night we would land on water — the Mediterranean, Nile River, Lake Victoria, Victoria Falls and finally the Vaal Dam, to be taken ashore by launch to a beautiful hotel while the Solent was serviced.

I was an enthusiastic five-year-old. The captain and crew became my new best friends. Every moment was an adventure, from the water swirling against lower deck windows during take-off to the wonders of the flight deck to the roar of the engines being run up every morning before departure. All those memories are still with me today.”

After Fenwick emigrated to the United States in 1974, business kept him from flying for an entire decade. However, after he sold his business, he got right back into the cockpit. “I bought a Lake Renegade for my beloved wife Olson, who flew our four children from Tanglefoot, our property on Priest Lake, Idaho, to school in Moscow, Idaho, an 80 minute twice-weekly flight each way.” Today, the same aircraft shares a hangar with a Goose and our subject aircraft, Mallard J57, the youngest Mallard in existence and one of only three that has never alighted in salt water.

Fenwick outlined the history of this wonderful flying yacht, “This aircraft was built for American Cyanamid Corporation in 1951…certified in the transport airworthiness category to meet the exacting needs of the executive market, J57 was factory-equipped to airliner standards with dual pitot-static and navigation instrumentation. It features a 50-gallon auxiliary fuel tank in each sponson and an individually operable left and right landing gear system that helps control in crosswind water operations. The Mallard is one of the most capable and beautiful aircraft ever built. This queen of seaplanes attracts admirers wherever she goes.”

Fenwick continued about his love for seaplanes and the Mallard in particular, “Seaplanes, especially flying boats can, in a few hours or even a few minutes, can take you to beauty and excitement that few ever see. But most of all, I appreciate the Mallard’s safety, from its Grumman Iron Works construction to its transport category redundancy to its gentle and predictable handling in the sky and in rough waters.”

The tragic and well-publicized crash of Chalk’s Ocean Airways G-73T N2969, which claimed the lives of 20 passengers and crew on December 19, 2005, nearly grounded all remaining Mallards. However, the Grumman Mallard Owners Association, which was founded at Tanglefoot Seaplane Base, represented Mallard owners in the FAA and NTSB investigation, helping to prove that N2969 had survived operation in severe ocean conditions before finally coming apart because of neglected corrosion and improper repairs. They also proved that properly maintained Mallards that had never been operated in salt water were in perfect shape with no structural deterioration whatsoever after 15,000 hours.

What is it like to fly this pristine amphibian from yesteryear? Addison Pemberton told Warbird Digest, “The airplane has delightful control harmony and effectiveness. The engines are very smooth, and the cabin is very quiet. I have to say 1,200-hp, and a full boot of right rudder for water take-offs, really gets the job done. The Mallard eased through weekend Priest Lake boat wake rough water like a China Clipper.”

In the end the Grumman Mallard, especially this youngest example that has only seen freshwater in six decades of flying, is a rare, classic flying boat, that can take a single pilot and ten adventurous passengers to wonderfully remote places in safety, comfort and nostalgic panache.

The Grumman Mallard J57 is for sale, for more information visit www.mallardj57.com

**An advertorial is an advertisement in the form of editorial content.