To read part one click HERE.

After his first emotions of relief subsided, he remembered that his troubles were far from over. He was many miles behind enemy lines confronted by miles of freezing, snow covered wilderness. His strength was spent from struggling to escape from the cockpit, and from the lack of food. His feet were wet and freezing; he was afraid of losing them even if they did manage to carry him out his plight. With these seemingly insurmountable odds stacked against him, he started out on his journey in what seemed to be the right direction to safety. After trudging on partially unconscious for a full day, he came to a farmhouse in the early evening. He hesitated outside, not knowing the type of reception he could expect. However, after a short pause, he realized that he needed food, warmth, and rest, and had to take the chance.

He stepped into the farmhouse, Luger in hand, and, partially by speech and partially by his sign language, demanded food. He eventually managed to convey his point and received his first nourishment in days. After eating he still did not know whether the farmer was helping him voluntarily or because of the Luger. Since he hadn’t slept for three days and nights, he sat down to rest. He tried to remain alert in case the farmer was not really friendly, but his fatigue would not allow him to stay awake. After several hours sleep he awakened and found that no harm had come to him. Gazing around the room he saw only smiling faces from the farmer’s family. At this time he decided he could trust the farmer and managed to convey the idea he wished to make his way west to the German lines. He persuaded the farmer to lead him, and they set out with a meager ration of food in a westerly direction. The main part of their trip was through a large, dense forest where the ground was covered with a deep snow. After many hours they finally came to the end of the forest. At this point, no amount of persuasion could convince the farmer to go on. Schmitz, after getting the best possible directions, considering the language barrier, proceeded alone. After plodding many more hours in what seemed to be an aimless fashion, he came to a point where he could see lights in the distance.

He cautiously approached the lights, not knowing whether they meant the enemy and death or friends, food, rest, and medical care. Since he was already at the point of collapse and had suffered so much, he had to take a chance. So he stumbled forward and luckily when he opened the first door, he was confronted with a German military doctor. The doctor cared for his frozen feet, gave him food and dry clothing, and put him to bed. The next day he was placed on a hospital train headed for Germany.

You would think that after this ordealhis troubles would be over, but the hospital train in reality was composed only of bare box cars, and they were filled with wounded soldiers. He and the rest of the occupants of his car lay there for three days without medical care. Many of them died during the trip. The soldier next to Schmitz died the first night but the body remained there because there was no other place to move him. Schmitz had to lie next to the body for the rest of the trip. As you may well imagine, he is very grateful after such a hardship to be alive and in good health today.

Experienced officers like Krupinski, Schmitz and Klaffenbach are very scarce in the new German Air Force. When it was decided to rebuild the German armed forces again, most people thought there would be many World War II pilots respond at the first request for volunteers. This did not happen, as most of the German World War II pilots had either established themselves in civilian life or were tired of the military. Consequently, in order to build up to its planned strength, the Luftwaffe had to recruit and train new young pilots.

In contrast to the older pilots with World War II experience, most of the pilots in the squadrons were trained since 1956. They are a new breed of pilot in the new German Air Force. They have great possibilities for advancement. Since there have been eleven non-active years in the German Air Force, there is a wide gap in age between the old heads and the young troops.

Therefore, when the older officers begin to think about retirement, these young officers will necessarily advance at a rapid rate. Two good examples of this are Captain Schultza-Raul and Lieutenant Kuebert who have recently been named squadron commanders in the Wing. Both are young officers, trained since the reactivation of the Luftwaffe. There were not enough experienced captains and majors to fill all of the supervisory positions, so these young officers were assigned the jobs on the basis of their abilities.

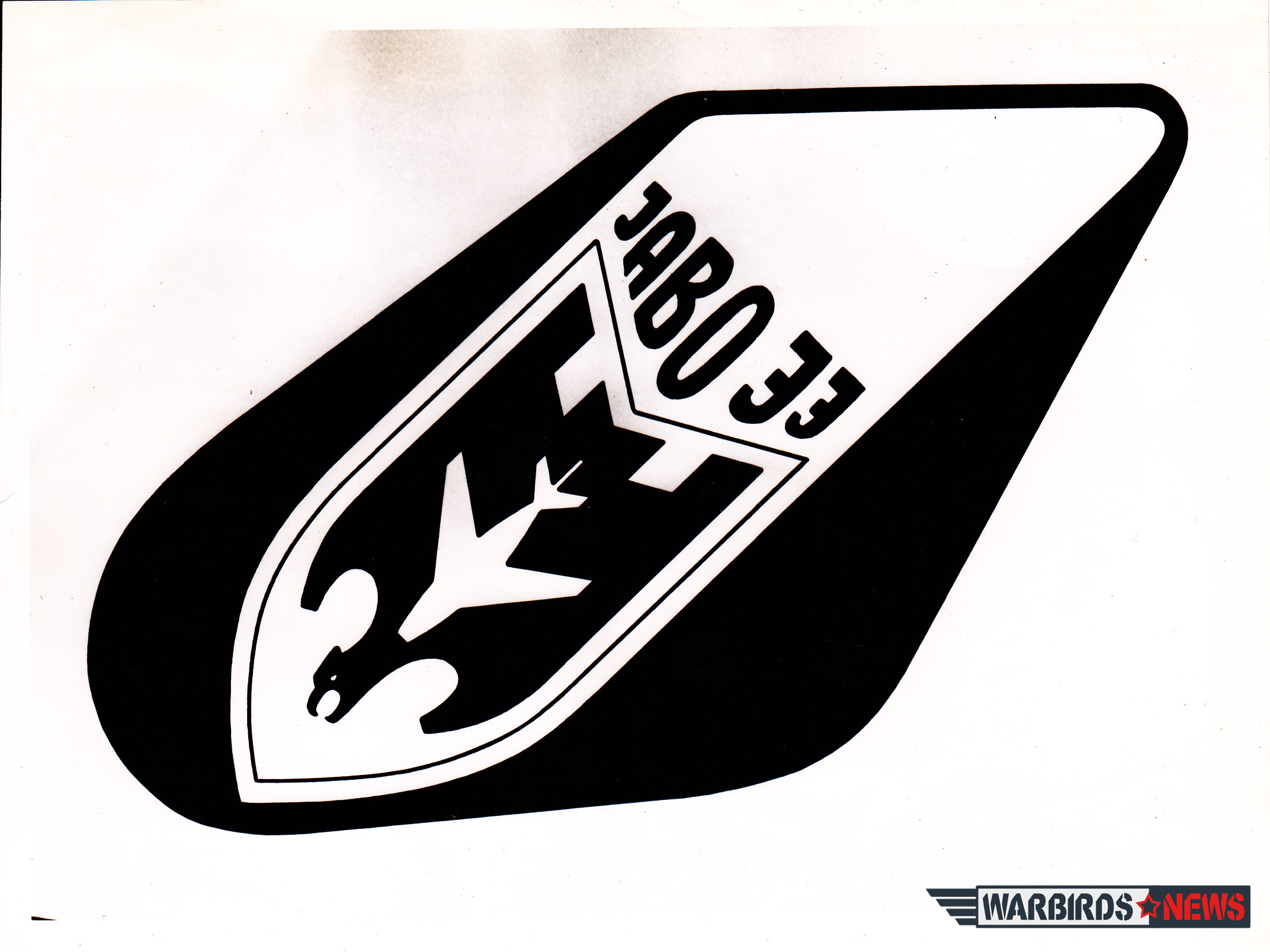

Some of the pilots are Lieutenants, some are Sergeant Pilots, all like to fly. Most of them were trained in the United States but Jabo 33 also has other pilots who were trained in England, Canada, and Germany. The German Air Force has now progressed to the point of training its own pilots, but initially the pilots received training in other NATO countries.

All the flying officers of the Wing speak English, and in the case of the younger pilots who were trained in England, Canada, and the United States, the accent in which their English is spoken varies from the very British to a resemblance of the deep South U.S.A., not to mention German. One officer, Lieutenant Gerd Gloystein, can imitate all of these accents in a very convincing manner. Due to the close proximity of so many different countries in Europe, it is not unusual for most of these people to speak not only German and English, but several other languages also. This is an area where much progress is needed in our country. Our armed forces and civilian personnel who represent us in foreign countries should be better prepared in the field of foreign languages. If we are going to assume our full stature of responsibility for world leadership, the people representing us overseas are going to have to be trained to speak languages in the countries in which their duties take them. A great majority of our personnel not only cannot speak several languages, but rarely speak one other than English.

The pilots of Jabo 33 are like Fighter Pilots all over the world. They like to fly, and they frown on what they consider the menial chores such as paper work and the like associated with ground duties. Occasionally a young lieutenant will approach me with a very discouraged look on his face, and a handful of disarranged papers. One such officer was Lieutenant Dietrich Schlicting. I invariably know what his problem is before he reveals that Colonel Krupinski has given him a duty of writing a SOP (Standard Operating Procedure) or some similar project, and he had to complete it before he can fly again. After I convince him he is really not as bad off as he thinks, I help him get started, and usually the next time our paths cross he is all smiles, his task completed, and he is back flying again.

In all good Fighter Squadrons there is a pleasant atmosphere; one of good spirits, comradeship and relaxation. This same atmosphere is found in the squadrons of Jabo 33. It is the same type feeling that you get when you enter any place where people are doing a job they like very well. This sometimes gives an outsider the impression of a seemingly lax attitude which throughout the years has often been misinterpreted by people who did not understand Fighter Pilots. In some cases they have been called such irresponsible names as jet jockies, fly boys, peashooter pilots, and many others. It is ironical but true that I have never heard a Fighter Pilot refer to himself by one of these names. This outward indication of a light-hearted attitude is really a reflection of spirit, eagerness, enthusiasm, confidence, aggressiveness, and, in some cases, cockiness, all of which are ingredients that go to make up a good Fighter Pilot. Fighter Pilots are doing a job that they like extremely well, and, in most cases, it is hard work. But, because they enjoy it, they look upon it as fun. Underneath there is a complete awareness of the importance of their mission. They are in most cases extremely serious, and sometimes the job of flying a single seat fighter can be a mighty lonely one.

THE THIRD AND LAST PART WILL BE PUBLISHED FRIDAY OCTOBER,4 2013.

Click on the book cover to buy it on Amazon.