By Liz Gilmore Williams

I flew into Honolulu in late March 2013, filled with excitement. The GPS device I’d brought from home refused to work as I drove my rental car out of the airport into the third-worst traffic in North America. Thank goodness I had directions to my rented condo. I found the place, 13 floors up on Kalakaua Avenue in Waikiki. The high point of the research I’d begun six years earlier, my trip to Honolulu proved invaluable to my quest to uncover the war story of my dad. My parents’ letters from World War II had sparked my project, urging me to sort them, to read them, to make sense of them.

For 57 years, the letters had braved the attic of my girlhood home in suburban Philadelphia. In torn-open, yellowed envelopes, the nearly 300 letters written from October 1940 to May 1945 bore strange addresses and stamps. Some letters Mother had scribbled in pencil; others were carefully scripted with her fountain pen. Some featured her lipstick-print kisses and smelled of floral-scented perfume. Stylish military insignia, airplanes, or tropical scenes adorned Daddy’s stationery. Handling the letters quickened my pulse. Who was Daddy as a young man? What did he do in the war? Was he even tempered before the war, as Mother said? Did the war plant a smoldering fuse in his head, sparking his explosions, or had something else? I’d hoped the letters could explain the mystery of my late father’s volatility. His death when I was 18 prevented my getting to know him well.

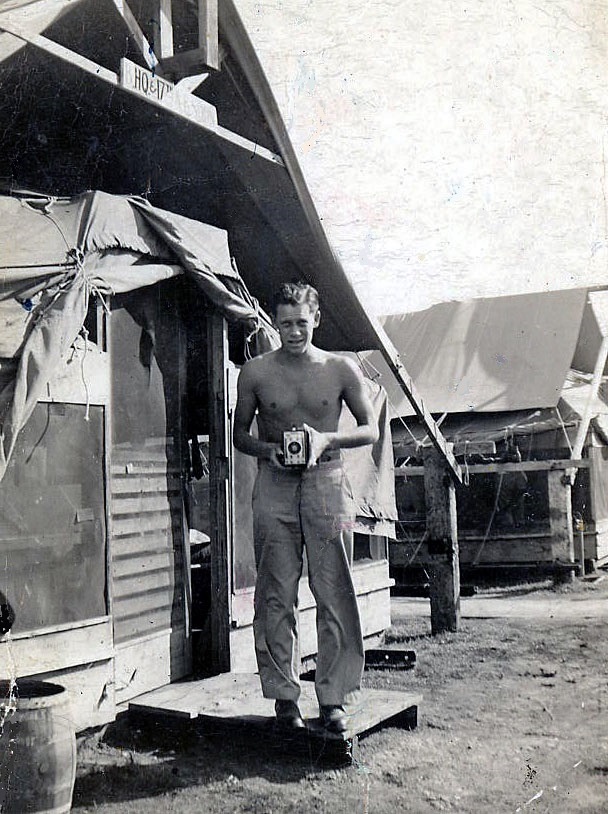

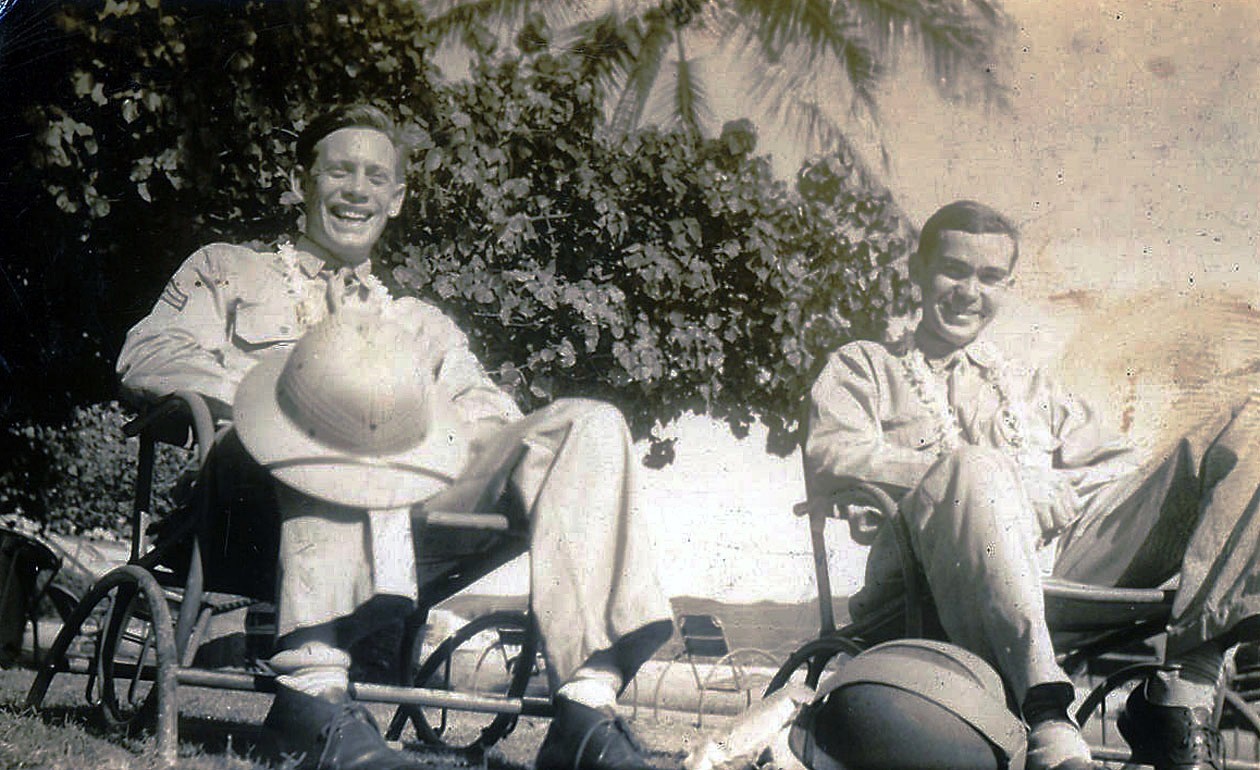

Once settled into my rented condo, I called Jessie Higa, who’d promised me a tour of Hickam Field, my dad’s post from July 1940 until February 1944. Jessie, a local historian, escorted me around Hickam, giving me an abridged history. Of Japanese heritage, she told me her grandfather had built the buildings on the base. The $1 million consolidated barracks, built in 1940, had been the largest such building of its kind on any U.S. military post at the time. Today an administrative building, the façade of the former barracks still bears the scars of December 7, 1941.Before the barracks opened, my dad, Herb Gilmore, and other enlisted men lived in 50-man tents in a temporary “Tent City” built near Hickam’s hangar line. The large canvas-roofed tents had wooden sides and floors and featured steel lockers and showers. The ambient air smelled like aviation fuel. In Tent City, the men used a separate kitchen, mess hall area, and dayroom tents, where they listened to the radio, nestled in easy chairs, and flicked the ashes from their army-issued cigarettes into smoking stands.

After leaving the admin building, Jessie and I walked to the base’s lush garden memorializing those killed in Pacific fighting. A reverence overtook me. On a perfectly Hawaiian day, palm fronds rustled and birds sweetly sang where whistling Japanese bombs once killed innocent boys, whose bodies had piled up where I stood. Native flowers seasoned the once smoke-blackened air. Suppressing tears and the lump in my throat, I shot photos, awestruck by the lives lost and my father’s survival. “Who would I be if Mother had married someone else?” I wondered. “Would I even be?” When the Japanese struck Oahu, Herb, a signalman, worked teletype in Hickam’s Bomber Command Signal Office in the Base Operations building. Japanese intelligence had mistakenly identified Base Ops as an officers’ club, which spared it. Herb relayed new developments from one headquarters to another and sent and took orders for the Commanding Generals. Only his helmet and the building protected him. Outside, dive bombers whined, machine-gun fire chattered, and bombs thundered.

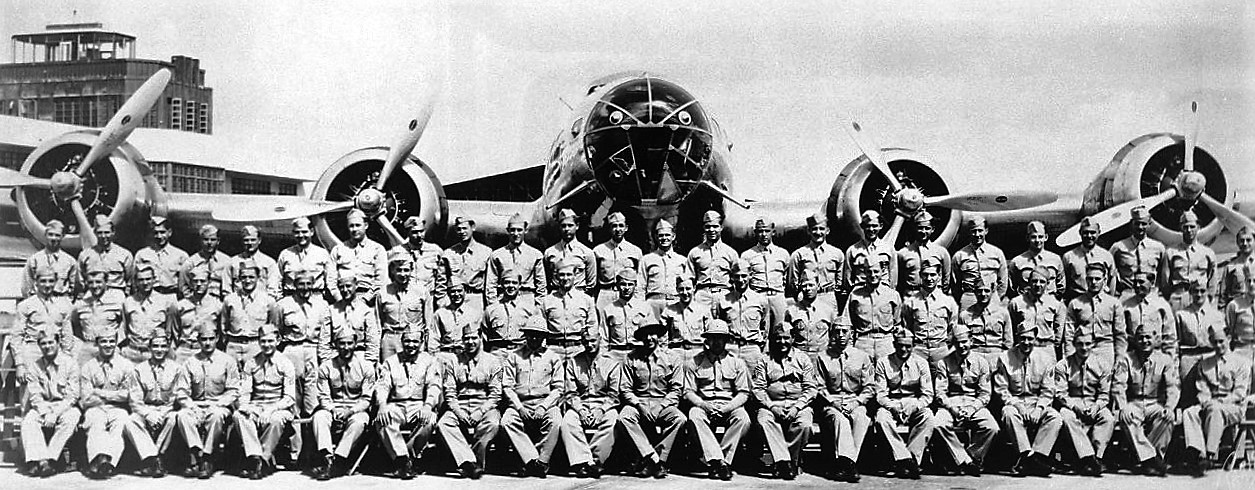

In the office of the base’s historian, I learned of oral histories about the attack done by men in my dad’s signal company. One of the histories mentioned my dad, confirming that he’d been on duty. Though Hickam lost 121 men, with 274 wounded and 37 missing, the attack claimed no lives in my father’s company. Herb, like many Americans, viewed Japan’s unannounced attack as sneaky. As the United States declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941, Americans rallied―none more than the airmen, soldiers, sailors, and marines on Oahu. They wanted revenge. Six months later, Herb’s organization, the Seventh Air Force, helped avenge the attack on Pearl Harbor. On May 30, 1942, 19 bomber and fighter planes from the Seventh flew 1,000 miles to take up a temporary station on Midway, ending the alert as all available forces gathered to defend the island. The next day, the bombers flew missions extending for 600 miles in search of the enemy fleet, returning to Midway on June 1. On June 3, search planes spied Japanese ships steaming toward Midway. Six B-17s from Herb’s command took off to attack enemy ships 570 miles from Midway. The Battle of Midway blazed for the next two days as army air force and navy planes struck enemy vessels. Extensive searches made by fliers on June 6 revealed no sign of the fleeing enemy. The battle barely damaged Japan’s navy but cut off part of its advance, proved the resolve of the Americans, and turned the tide of the war in the Pacific.

In the ensuing months, Herb’s command, the VII Bomber Command, would participate in softening up Guadalcanal and other islands on the road to Tokyo. Though Herb remained at Hickam for a while, he left for the Gilbert Islands in February 1944, only the first of his stints on primitive and sparing islands in the Pacific. During his four and a half years of service, and especially his combat tour of the islands, Herb’s letters from his wife, Ann, sustained him. The single most important morale booster during World War II, mail meant everything to servicemen. As Herb wrote, “Certain guys live from day to day just for a letter, and when it doesn’t come, they feel sad. A little thing such as a letter means so much.”

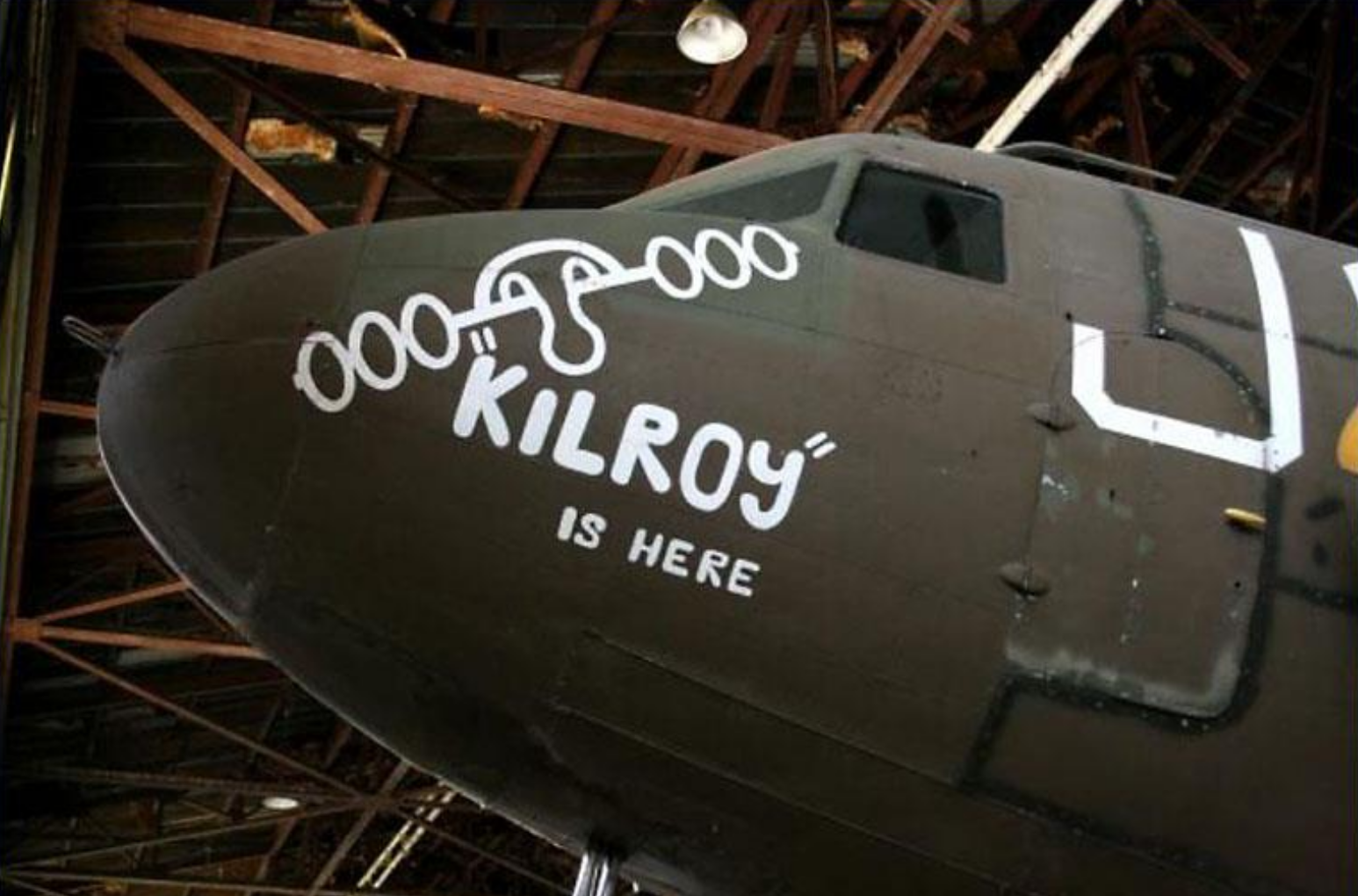

My dad’s war experience so intrigued me that it formed my book, No Ordinary Soldier: My Father’s Two Wars. From the letters and eight years of researching other sources, I crafted the book from the viewpoint of a soldier—and his wife. My dad’s organization, the unsung Seventh Army Air Force, flew longer missions and more diverse aircraft than any other U.S. air force in the war. My research and writing not only revealed the achievements of this force but brought the war home and gave me the answer to dad’s explosiveness. The sacrifices of young men and women such as my parents cannot be overstated: They gave all they had for our freedom and wellbeing.

###

Liz Gilmore Williams published No Ordinary Soldier: My Father’s Two Wars in December 2016, on the 75th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor. In addition to this book, she has published four essays. Learn more about her book at www.noordinarysoldier.com.

Congratulations on your book and the satisfying research on your father’s service.

I would offer a different and historically accepted viewpoint to your assessment of the Battle of Midway where you say that “The battle barely damaged Japan’s navy…”. At Midway, the Imperial Japanese Navy lost four aircraft carriers, one cruiser and 261 naval aircraft. These were four of the six capital carriers that attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Equally important, the IJN lost a significant portion of their trained and experienced cadre of naval aviators which was surpassed only by the Battle of the Philippine Sea or “The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot”. This significant loss at Midway by the IJN did “…cut off part of its advance, proved the resolve of the Americans, and turned the tide of the war in the Pacific.”