The aviation community is one giant family. Despite how many licensed pilots, mechanics, dispatchers, and other countless ground support staff there are, everyone seems to be somehow connected. Aviation is a large but close-knit community. Those who fly are often led into the industry by those close to them, such as a parent, grandparent, or friend. In the case of warbird restorer and pilot Mike Porter, a lifetime in aviation seems predetermined upon his birth. Born in 1980, Mike’s early days of living were spent growing up on the New Jersey shore. His dad, Andy, was a commercial pilot and flight instructor who, at that point, had around 20 years of experience. Mike’s father ensured he had aviation exposure from a young age. His first visit to the airport was at two weeks old, a familiar theme amongst many of us pilots, it seems. Mike’s first word was “plane,” which he uttered while pointing to a Stearman. This would serve as an omen for his aviation career ahead.

Growing up, Andy Porter always had some sort of airplane. He’d buy one, fix it up, fly it for a bit, and then eventually sell the plane. This cycle repeated for years, with incremental “trade-ups” happening along the way. Mike learned from his father the value of not only repairing aircraft but also enjoying the process. In the early 1990s, Mike’s dad became involved with a friend who had a Stearman rides business in New Jersey. This family friend needed pilots for the upcoming summer flying season, which already had sold out on rides. Andy Porter would fly biplane rides for his friend that summer and Mike was right alongside to help load and unload passengers before and after each flight. This became a summer tradition, continuing each year in the early 90s.

In 1992, one of the businesses’ PT-17s was in need of an engine overhaul. The decision was made to do the overhaul in-house, and the effort would be led by a gentleman who was an A&P and mechanic instructor post-WWII. This mechanic had limited mobility but was willing to teach once again. “Hey, you’re interested, you’re quiet, you want to learn. You pick up the parts, and I’ll show you how to do it as we go.” From there, Mike’s interest in and skills in Stearman repair began to take off. Around age 11 is when Mike’s hands-on experience with the Stearman began to blossom. In between helping turn wrenches and re-skin the aircraft, Mike and his dad would fly in the Stearman together routinely, having some impromptu flight lessons along the way. The lessons would build his comfort in the WWII biplane, and on his 16th birthday, Mike soloed the Stearman. Shortly after, Mike graduated from high school early and pursued training as an airframe and powerplant mechanic at age 18. At the same time, he went on to earn his commercial pilot’s license and build time-flying tailwheel aircraft. At 23, he earned his IA (Inspector-Airframe.)

Shortly after graduating, Mike Porter began doing work as a mechanic and really “got heavier and deeper into that.” He began giving Stearman rides, just like his father had. On top of this, Mike flew banner towing gigs with the L-19. Mike had built up a considerable amount of flight hours, and had his sights set on a job flying for the airlines. Unfortunately, this was at the same time 9/11 changed everything in the aviation industry. This threw a wrench into Mike’s plans, but he didn’t let the challenge interfere with his desire to work with aircraft. One of the benefits of no one flying was that there was downtime for their aircraft to be maintained and upgraded. Mike saw this as an opportunity, and he began to do subcontract work with existing aircraft maintenance shops to help ease their overwhelm. From this subcontracting was born Mike’s business in aviation restoration.

In 1997, the Porter family bought their first Stearman. About the aircraft, Mike says, “It was, let’s say, flying on a wing of a prayer. It was old, tired, and beat up from rides.” The aircraft may have seen better days, but it had good bones. Most important of all, it was within the family’s budget. This Stearman would go on to receive lots of love from the Porter family, initially just to get airworthy again. The plane was flown locally, while in between flights and during the “off-season” more upgrades were made. The PT-17 was a flying restoration. The efforts of Mike and his family began to draw attention. Soon, other owners of Stearmans in the area began to ask for help with their aircraft. This was during the time period shortly after 9/11, when Mike’s aircraft maintenance services began to ramp up. The airlines eventually did come calling for Mike, but he found that the maintenance business was supporting him, and he could be his own boss. He stayed the course.

Mike began doing “minor” restorations on Stearmans, such as aileron recovery, wingtip repairs, and ground loop damage remediation. His parents decided to move to Texas and take the “show on the road,” but the location wasn’t a good fit. Eventually, the family found themselves in East Liverpool, Ohio, where they remain today. It was in the northern midwest that Mike would find opportunities to get more into working with PT-17s. He met a gentleman by the name of Jack Roethlisberger. Jack has been building a full-scale Spitfire replica in Beaver Falls, PA. At the time, he had 6 Stearman projects that he needed to complete for customers and/or friends. The two men went out for a lunch meeting, and within an hour, Jack said, “Mikey, you need to do work? Here. Here are six airplanes. Here’s what I can pay you a week. Get going.” Just like that, Mike Porter was in (even more) business.

In a true test of “trial by fire,” Mike set to work on the Stearman airframes. He worked on these projects for years, completing 4 of them when his family got the itch to do a complete restoration on their own PT-17. Mike had amassed enough spare parts, and gained enough experience at re-skinning the aircraft to make a good run at a full-on restoration of the Stearman. In 2006, Mike began the process of “scalping” the family Stearman. Within 11 months, he had the aircraft not only completely re-skinned but airworthy once again. The airplane had been totally rebuilt from the ground up. New fabric, wood, wiring, and an engine overhaul made the PT-17 a factory-fresh machine. It’s safe to say the Roethlisberger projects gave Mike good practice, as everything on the family Stearman restoration project was done in-house, and nothing was sent out or outsourced. A true labor of love.

The Porter family Stearman is not just your “typical” PT-17, the aircraft has a unique history. 41-25714 was flown by the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) during WWII. The WASPs were a group of civilian women who were tasked with ferrying aircraft, towing targets, and training other pilots during the war. From the moment that the Porter’s acquired the Stearman and learned of its provenance, the goal was to restore the aircraft to the original paint scheme and configuration. From the time of purchase in 1997, to the restoration in 2006, Mike scoured the earth in every photo archive he could, in an attempt to find an original photo of their airframe. Eventually, his efforts proved fruitful and a photo was found. From here, he knew how to complete the restoration and give the PT-17 its original looks. The aircraft now appears just as she did during World War II, while being flown by the WASPs.

When working on historical aircraft restoration, Mike Porter takes a balanced approach by blending authenticity with user-friendliness. Aircraft flying today need equipment that wasn’t standard back in the 1940s to be considered safe and legal in the US airspace system. Transponders, ADS-B, radios, ELTs, all of these items are necessary to ensure pilot safety. Mike finds a way to restore aircraft as close to their original condition as possible while still complying with the FAA’s modern airworthiness requirements. Installing the modern radios out-of-sight in the map case is one tactic that has been used to make the aircraft appear to be straight out of WWII. This is a delicate balance, but Mike handles it time and time again.

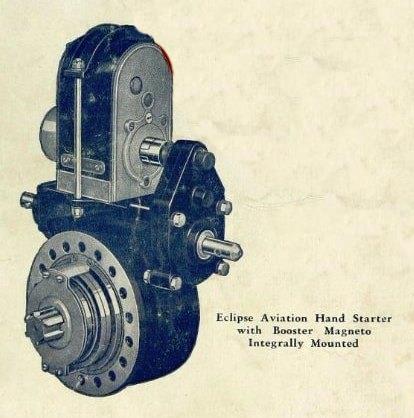

Originally, the PT-17 was started inertially. A ground crew member would stand on the left gear leg, crank a flywheel unit up until it made an audible screaming noise, pull a lever, and then the engine would roar to life. Though a performative art, modern Stearman owners mostly want a more convenient and safer option. Mike remedies this issue by installing an electrical charging system in his clients aircraft, if they so desire. This allows for starts without all the hassle. Mike also does upgrades to the PT-17’s brakes, which weren’t known for being the best originally as they had a tendency to grab and lock up. Not ideal when you really need to use them. With proper maintenance, the original brakes are generally safe, but a modern disc-brake conversion proves much more effective. If nothing else, the conversion offers peace of mind.

Of the aircraft’s overall reliability, Mike says, “Stearman is a pretty good design as far as that’s concerned for usability. It doesn’t need much.” The fabric covering originally used on the PT-17 was cotton with nitrate “dope,” a glue-like substance. Cotton isn’t known for lasting long, and nitrate is flammable, “you might as well be flying a bomb.” Here, Mike employs ceconite polyester in place of the cotton and urethane-based primer and paint. This is flame retardant, chemical resistant, much safer, and far more durable than the original covering.

An aircraft restoration is no easy task, and Mike Porter knows this all too well. However, in Mike’s opinion, the largest obstacle to renewing an airplane isn’t the cost, or the parts availability, it’s the skillset required to make the magic happen. Older aircraft require maintenance people with a real “know-how,” including a knowledge of how it was built, the materials used, and the hands-on skill to be able to do the work necessary. Woodwork, sheet metal, welding, wiring, a whole can of worms open up on an aircraft restoration project. Having the knowledge to face a project head-on with confidence is the key to keeping Warbirds flying. This knowledge and skillset doesn’t develop overnight; it takes years of practice and repetition to nail down, just like learning to fly World War II aircraft. It helps to have a “sensei” along the way, as well. Additionally, the time requirement is often underestimated or overlooked. A vintage aircraft project is a massive undertaking, and what may seem simple can actually be a multiple-day process, such as rib-stitching. Mike does most everything himself, with a little help from his dad on occasion.

The Boeing PT-17 Stearman was also known as the Model 75. It wasn’t the first Stearman design; it was drawn from the Stearman Aircraft lineage. The Model C3 first flew in 1927 and was used extensively in mail-carrying operations. As aviation grew and developed, the Model 75 came to fruition from what had been learned of biplanes during their use in the 1920s and 1930s. The cockpit of the PT-17 is more streamlined, has a better layout, and is overall more comfortable than earlier biplane aircraft. This cockpit familiarity proved to be vital once the Stearman began being used as a Primary Trainer in WWII. Going from a PT-17 to a BT-13, to an AT-6, and then to a P-51 Mustang, “everything feels like it’s in the right place” in the cockpit. This made the transition process much more tolerable for cadets during the war.

Mike’s favorite restoration project to date has been his family’s original WASP Veteran, Silver Number 12. This is the aircraft that got him going and has remained by his side ever since. At Oshkosh, this PT-17 has won the Silver Wrench and Grand Champion Awards in recent years as Best Primary Trainer. The WASP machine has ~1,700 hours on it and still flies like the day she came from the factory. Mike describes the aircraft as “the gift that keeps on giving.” He has taken it all over the country, meeting and flying with original WASP pilots along the way. This PT-17 has also opened many doors, or cockpits, for Mike. He has had the opportunity to fly the P-51, B-17, and other famous WWII aircraft as a result of his experience in handling the Stearman.

Projects that roll into Mike’s shop run the gamut in terms of overall repair needs. Some jobs are simple and can be done over a few weeks of “downtime.” Other, more in-depth projects can require 18 to 24 months of TLC. Parts aren’t too hard to source, but the time-consuming factors are the location of materials like wood, paint, sheet metal, and the like. This is due in large part to aftereffects of the global pandemic. When not working on PT-17s, Mike also has a specialty in working with T-6s and over “heavier iron” from the time period. He ferried airplanes for customers, and will also provide flight instruction for them in their aircraft if requested. To summarize, Mike states “general maintenance inspections, full restorations, repair work, occasional airshow events for static display or fly-bys…that’s pretty much what we do.”

Mike Porter has more interesting projects in the queue, and the warbird world eagerly awaits their completion. His admiration for the aircraft that got him started still remains strong to this day. “One of the reasons why I love a Stearman is it’s an antique, it’s a biplane, it’s a military or plane. It crosses a lot of different areas historically, just for the old fun romance of a biplane and lots of good fun.” There are no limitations from the FAA as to the operations of a PT-17, and they are typically registered with standard airworthiness privileges. You can sell rides, fly airshows, offer flight instruction, the only limit is your imagination. A nicely restored and equipped Stearman could easily cost in the neighborhood of $350,000 today, a testament to its prestige and significance. However, it is still a humble flyer’s airplane, despite what the marching of time has decided the aircraft is worth. The operating expenses for such an airframe greatly depend on the owner’s location and flying habits, but the amount is not astronomical in comparison to other privately owned higher-performance aircraft. The annual inspection on a Stearman is usually a couple of thousand dollars. The fuel expense is 12-14 gallons per hour, multiplied by your local AvGas rate. Insurance rates can be in the hundreds or up to the thousands annually, depending on the pilot and location.

The PT-17 continues to soldier on, proof of the aircraft’s rugged design and longevity. Mike estimates around 1,500 Stearmans still exist in various conditions. When Boeing built them during World War II, they made 10,000 Model 75s. However, 1,500 of these were incomplete, held in reserve to be finished later or for spare parts. This is the reason so many parts are still available today; these caches of extra components still exist around the world. Having a plethora of parts on hand to keep the PT-17 flying is a huge asset, but why else does this aircraft continue to soldier on? “It’s a very good airplane. It’s a very maneuverable airplane. It’s strong. It’s, as far as designs go, a simple and robust design. As long as you use common sense, it can be changed and altered very easily, as far as most airplanes are concerned.”

Mike Porter recognizes how useful the PT-17 was. He attributes their versatility as primary trainers in World War II, and as crop-dusting and flight school trainers post-WWII as the reason so many still fly today. “They (Stearmans) were there and able to serve a need very quickly. So, I would say that’s why they survived.” The warbird industry is very lucky to have Mike amongst its ranks. He has a wealth of information and skills that are sorely needed to keep these warbirds flying. His story inspires us, and we thank Mike for his dedication to keeping them flying.

![Planes of Fame Air Museum Receives a New Stearman 14 PT-17 Stearman 41-8746/N555BF arrives at Chino. [Photo via Planes of Fame]](https://vintageaviationnews.com/wp-content/uploads/Planes-of-Fame-Air-Museum-accepted-the-donation-of-a-Stearman-PT-17-150x150.jpg)