by Grant Newman

A recent visit to the Omaka Aviation Heritage Centre Dangerous Skies exhibition enabled a closer look at the Smith family de Havilland Mosquito FB.VI TE910 that has taken up residence at Omaka. On loan to the Aviation Heritage Centre, the Smith family Mosquito’s background has been covered here before (see article HERE), but one aspect of the aircraft’s history is not known; it’s link to RAF East Fortune in Scotland. Uncovered during the restoration of its propellers was graffiti linking the aircraft to the former RAF station, which is situated in East Lothian in rolling countryside twenty miles east of Edinburgh. Remarkably preserved thanks to the efforts of John Smith of Mapua, Tasman, New Zealand, this veritable time capsule of an aircraft is largely in original condition, with concessions made to enable it to be ground run. To do this, the aircraft’s propellers required overhaul, which was done by Airbus at its on-site propeller overhaul facility at Woodbourne, Marlborough in New Zealand’s South Island.

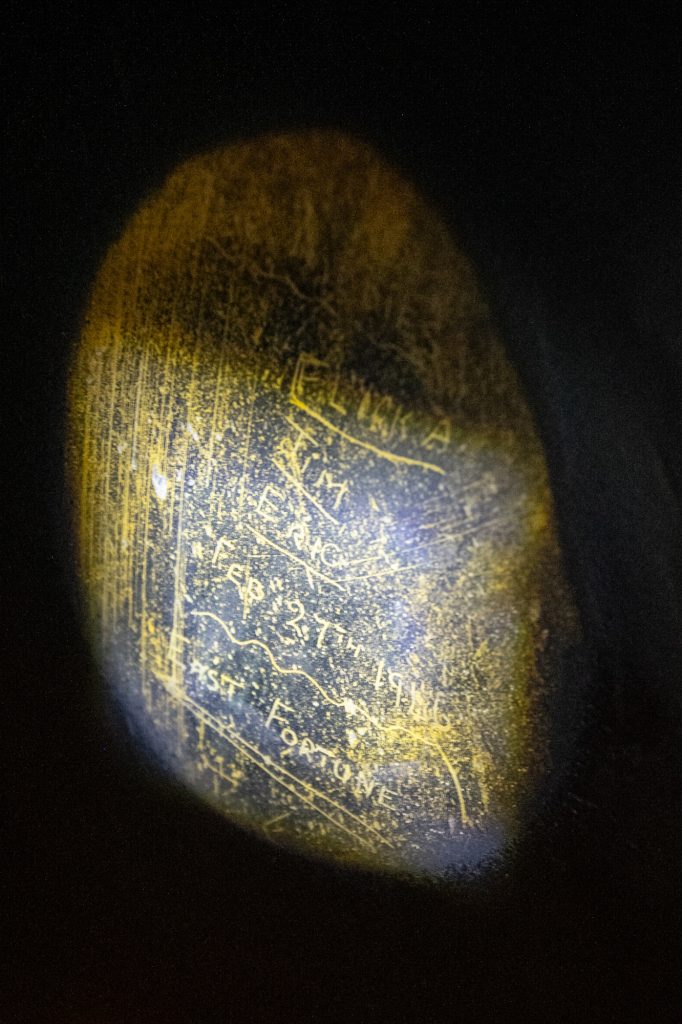

Graffiti was discovered on the back face of one of the blades on the left hand propeller, which was carefully kept by the Airbus engineers. It reads: “The kiddies, Flicka, Tim, Eric, 27 February 1946, East Fortune.” What is unusual about this is that TE910 never went to East Fortune, so some explanation is required as to how this unique piece of history ended up on this aircraft that travelled all the way to New Zealand in 1947. RAF East Fortune is a historic site. In July 1919 the rigid airship R.34 took off from there and flew to New York on what was the first east-to-west and return Atlantic crossing by an aircraft. During the First World War, East Fortune was a Royal Naval Air Station, established for air defense purposes against the threat of raids by German airships against the Scottish capital. Its primary purpose was housing airships for anti-submarine patrols around the British coast. Following the end of the war, the massive airship sheds and the hydrogen processing plant were dismantled and the station buildings were converted into a tuberculosis sanatorium.

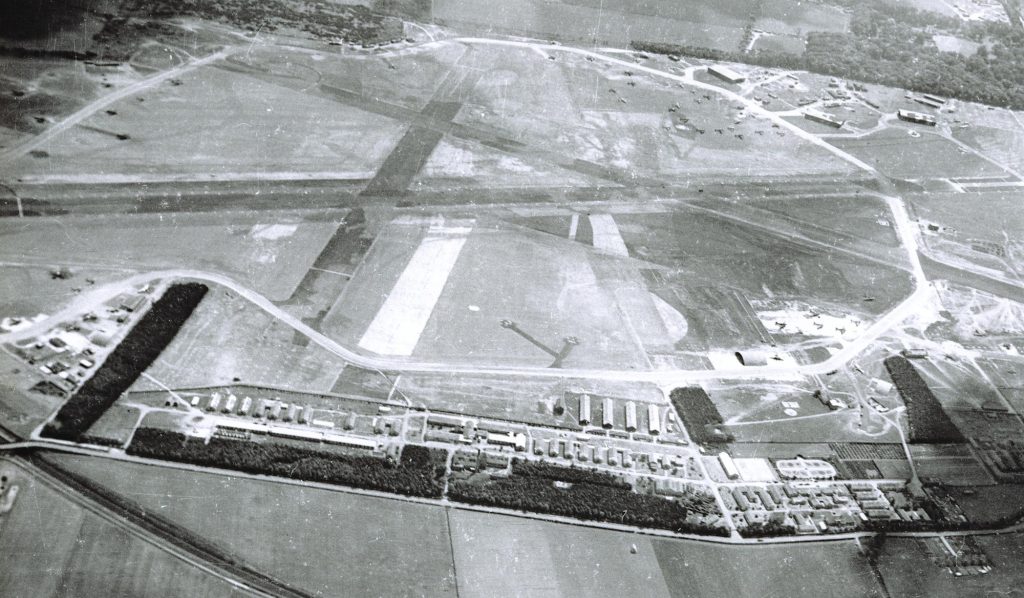

With the outbreak of war in 1939, East Fortune was requisitioned by the Air Ministry for development and by 1941, three concrete runways, three maintenance hangars and off site accommodation had been constructed to house an influx of aircraft and personnel for its wartime role. Officially opened in 1941, RAF East Fortune became home to No.60 Operational Training Unit, a night fighter training unit that saw hundreds of keen young pilots and gunners learn the art of night fighting on the Boulton Paul Defiant two-seat turret fighter. Incidentally, 60 OTU was numerically the largest operator of the Defiant. In late 1942, 60 OTU was disbanded and No.132 OTU, Coastal Command took up residency at the airfield. This unit was established to train aircrews in anti-shipping strike on Bristol Beauforts, Bristol Beaufighters and from 1944, de Havilland Mosquitoes. To house the newly arriving Mosquitoes, a fourth hangar was added to the three existing buildings on the south side of the aerodrome. The types of Mosquito based at East Fortune were T.III training variants, as well as FB.VIs and a small number of NF.II night fighters. Following the end of the war, East Fortune remained open until the end of 1946, within which time, anti-shipping strike training continued on the Mosquito. By early 1948 the RAF station had closed and the sanatorium reopened. The south side hangars and buildings are currently occupied by the National Museums of Scotland’s aviation holdings as Scotland’s National Museum of Flight.

To determine what the Mosquito’s connection to East Fortune is, a bit of background is required into the type of propellers fitted to the Mosquito and their overhaul procedure. The Mosquito FB.VI was fitted with de Havilland Propellers 23EX constant speed propellers, which were license-built Hamilton Standard 23E50 Hydromatic propellers. The name “Hydromatic” was a Hamilton Standard patented product name, which described the method by which the blade angle was altered. This was done through differential oil pressure acting on a piston mounted inside the propeller hub. The forward and aft movement of this through a moving cam changed the blade angles through serrations at the butt of each blade. There was a difference between the de Havilland and Hamilton Standard propellers in the splines molded into the spider within the propeller hub. The spider was a three pronged centerpiece to which the propeller blades fit, with a center orifice. The spline within this enabled fitting to different engine types, the de Havilland manufactured spiders had a different fitting for British-built engines to the Hamilton Standard manufactured ones. This means that propellers fitted to British engines cannot be retrofitted to foreign built engines without changing the spider in the center of the propeller hub. Other components within the hubs could be interchanged, however. The blade part numbers were interchangeable on Hamilton Standard and de Havilland propellers, although blades had to be shaped by hand for different applications. Bigger blades could be cut to size and reshaped by hand, judging the shape using the good old “eye-ometer” to match their new application.

During the war, propellers were overhauled in specific depots and blades and individual components were interchangeable between propellers of the same type. A 23EX propeller from a Mosquito FB.VI could share components, including propeller blades with other Mosquitoes or indeed other aircraft that operated the same type of propeller. During overhaul, dimensions were taken at different stations across the blades to measure their thickness and width, which determined whether or not they were serviceable and could be used again. Individual blades were kept at servicing depots and these were overhauled and placed in stock for future use. Individual blades were not serialized, so tracing them to an individual airframe is virtually impossible. This means that at some stage, the left hand propeller of TE910 was fitted with a blade that had been fitted to a Mosquito that had been resident at East Fortune. The difficulty is tracing when that blade was fitted to TE910. Was it when it was built or while the propeller was undergoing overhaul during its service career? The answer requires a bit of guesswork.

On completion of its fuselage and wings at the Standard Motor Company at Coventry, TE910 was sent by road aboard an RAF Queen Mary trailer to 27 Maintenance Unit at RAF Ansty, to the east of Coventry, where its engines and propellers were fitted before delivery to the RAF. In what was a mammoth flight for the time, in 1947, 80 Mosquitoes were flown from Britain to New Zealand to start a new career in Royal New Zealand Air Force hands. Included among them was TE910, which was re-serialled as NZ2336. On withdrawal from RNZAF service, the Mosquito had flown a total of 80.35 flying hours. Because this is not a high number of hours, there is the likelihood that the propeller never received an overhaul during its service career, which means that the blade was already fitted to the propeller when it was attached to TE910 on completion at Ansty. As previously mentioned, it is virtually impossible to determine which Mosquito the blade was fitted to when it received the graffiti, but it adds a unique dimension to the rich career of this aircraft. There is one more question that requires answering; who were Flicka, Tim, and Eric and what were they doing carving their names into the propeller blade of a de Havilland Mosquito at East Fortune on 27 February 1946?

Dehaviland left it mark on World Aviation history in superb style with all its various models.

Being a Southland farmer the Tiger moth destroyed the rabbit plague with pollard poison and superphosphate which made the grass grow and the baby rabbits couldn’t survive Being wet .The Tiger moth also spread Basic Slag fertilizer a byproduct of the German steel industry. As a Gorse spray plane it was better than any Hellicopter as there was no upwards swerlling of wasted 2445T spray which could be blown away and wasted. It has a slow stall speed almost as slow as a Hellicopter ,and only required a short airstrip.Just remember Dehaviland built the World’s first passenger jet and the Mosquito the fastest World War ll fighter Bomber