From an original article by By Tara Copp/Stars and Stripes

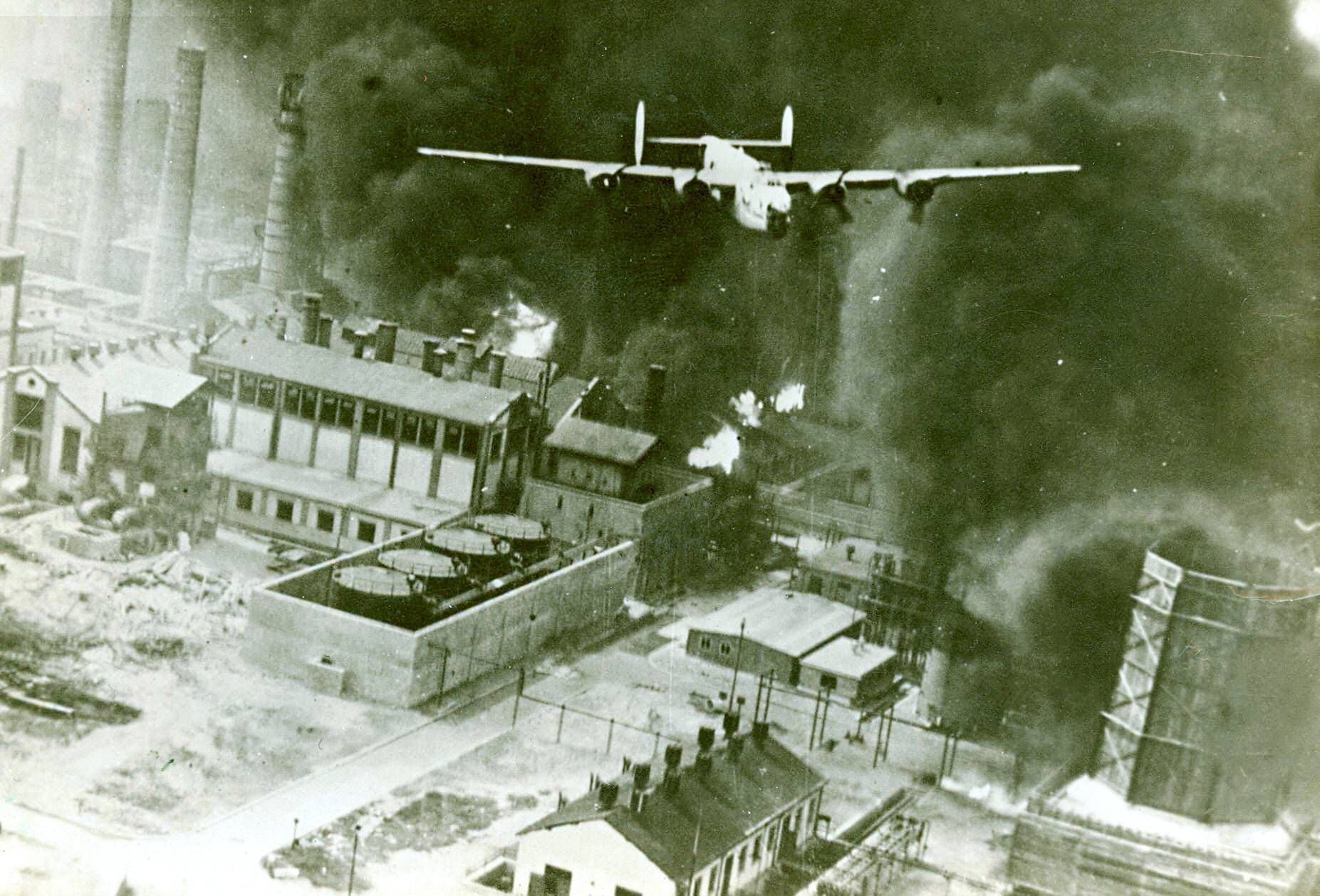

The pilot in one of the most iconic air battle photographs of World War II wonders whether the Pentagon really thought things through before naming the current air campaign to destroy Islamic State oil Operation Tidal Wave II.The original Operation Tidal Wave was an Aug. 1, 1943, mission to destroy Hitler’s main oil supply in Ploesti, Romania — the deadliest single-mission air loss in U.S. history.In the famous photograph, a single B-24 Liberator punches through a wall of black smoke just as it has cleared its burning refinery target. The famous bomber was named The Sandman, and its pilot, then 1st Lt. Robert W. Sternfels, isn’t sure the Defense Department knows how very wrong things went that fateful day in 1943.Despite the losses, the mission itself had multiple acts of extreme heroism as airmen pushed through the dangerous target – five Medals of Honor were awarded that day, and the long-range attack – a 2,600-mile round trip — was the longest run accomplished to date.But it came at a cost.“I think it’s terrible,” Sternfels, now 95, said from his home in Laguna Woods, Calif. “The people that selected that … really don’t know what happened.”

Earlier this month, Central Command announced the namesake mission, with a similar goal. In the same way that the U.S. went after Hitler’s oil supply – in wartime, oil was essential for Germany’s ground and air operations to succeed – the U.S. military is going after the Islamic State’s supply. The terror group has made it a priority to take over refinery cities in Iraq and Syria, and use the revenue from selling the oil to fund its operations. Central Command launched Tidal Wave II on Nov. 8 to shut down that funding source. Unlike the original single-day mission, Tidal Wave II is ongoing; the U.S. military said Monday that it had destroyed 283 tanker trucks used to smuggle oil from eastern Syria mainly to Turkey, where it is sold at a reduced rate to generate about half of the militant group’s income.

Target: Hitler’s oil

After weeks of practicing in extreme heat, where crews flew in formations just 100 feet over the Libyan desert, 177 B-24 Liberator bombers took off Aug. 1, 1943, as part of Operation Tidal Wave. They flew from their North African base in Benghazi to land a crippling blow to oil refineries in Ploesti. The refineries were producing an estimated one-third of Hitler’s oil, and the U.S. Army Air Forces planned a massive run against the target to choke off the supply.Multiple waves of B-24s from the 98th, 376th, 44th, 93rd and 389th Heavy Bombardment Groups flew in — some 300 to 500 feet off the ground, others as low as 100 feet off the ground — to surprise and destroy their target.

But the Germans were waiting for them.They lit smoke pots to obscure the area, and once U.S. aircrews started bombing the refineries, thick black smoke from the fires made it impossible to see. German fighters dove and shot at the formations, sending bombers crashing to the ground. The crews faced heavy anti-aircraft fire, and several bombers hit thick wire traps that the Germans suspended from balloons over the target. In that single-day strike, 54 bombers did not make it home and 532 airmen were killed, according to “Combat Chronology, 1941-1945,” an official reference maintained by the Air Force Historical Studies Division.

Hitler’s refineries, while damaged, survived this deadly attack. It would take another year of relentless bombing, more than 13,000 tons of bombs and the loss of an additional 2,000 airmen before Ploesti would fall in August 1944.When Sternfels questions the naming of the mission, it’s because he believes serious navigational mistakes that day led to the unnecessary deaths of too many airmen and the failure of the mission to do lasting damage to the refineries. Col. Keith K. (K.K.) Compton, commander of the 376th bombing group, led the waves of bombers and had the first wave turn too early, Sternfels said. That mistake led them to Bucharest, not Ploesti. In correcting the wrong turn, Compton’s lead group missed its assigned target, the Romana Americana refinery – the most important of the targets, according to the U.S. Air Force Historical Support Division — and the refinery was back to normal within months.“Virtually every study on the Ploesti attack stated that the damage was not at all significant and had little impact on either overall German oil processing or on production at the Ploesti refining complex,” said Archangelo “Archie” DiFante, a senior research archivist at the U.S. Air Force Historical Research Agency at Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala.But the importance of that mission went beyond destroying refineries, DiFante said.“It showed the world, especially the enemy, that despite their losses, the [U.S. Army Air Force] heavy bombers could reach and attack targets deep within German held territory and return.”

The Sandman’s flight

Ploesti was on fire and heavy with smoke from Compton’s earlier wave of attack when Sternfels’ group reached the refinery, so the bombers in his formation used train tracks to guide them.But the Germans were ready for that, too, and had 88mm guns mounted on flat railcars. Haystacks along the route began to open, revealing heavy anti-aircraft guns.The Sandman and the other bombers in its wave of attack were moving in at 200 mph, and it was very difficult to keep the bomber under control, Sternfels said. He had his co-pilot, 2nd. Lt. Barney Jackson, grip the bomber’s wheel and both men fought to keep The Sandman level as it flew through the prop wash of the bombers swarming ahead of them.As Sternfels looked out his window at the gun train below, he said he flashed back to the carnival games he saw as a child, where people would pay to shoot at fake ducks that were pulled across a carnival barker’s game stand on a chain to win a prize.Except here, he recalled, “we were the ducks.”The bombers that survived were the ones closest to the train, because the rounds were on time-delayed fuses that did not explode fast enough to destroy the Liberators closest to it.

The Sandman pushed into its target, completely enveloped by the smoke. Liberators around him were hit and had engines and bomb bays on fire. They saw some men bail out whose parachutes failed to open. In his mission report of that day, Sternfels and his crew reported seeing 11 bombers around them on fire, breaking apart or crashing.He said he couldn’t think about bombers he saw going down: “I was worried about my survival. I had no feeling.”As soon as he dropped their bombs over the target, bombardier 2nd Lt. David Polaschek used the interphone to reach his pilot.“He said, ‘Let’s get out of here!’ ” Sternfels recalled. “I said, ‘I’m doing the best I can!’ ”

Capturing the moment

When the iconic photograph was taken, Sternfels and his crew had just emerged from the smoke. He was flying 200 mph about 150 feet off the ground.“We went into the smoke and fortunately we came out of it at a moment where I could see the smokestacks. I was headed right for them.”Several brick smokestacks about 200 feet tall were directly in front of him. Based on the length of his bomber’s wings – which were each 55 feet long – he believes he missed the smokestacks by only 35 or 40 feet.“It was pretty close,” he said. “I didn’t have time to think about it. I was busy trying to correct to save the moment. I wasn’t thinking in the future. I saw them and I pulled up and turned.”Another Liberator flying ahead of him captured the moment in a photograph. Once the aircrews returned with the film, the image was selected to distribute to newspapers and quickly became a favorite used to tell the story of the danger crews faced that day.But the iconic image of that moment is actually backward, Sternfels said.Because of the extreme combat over Ploesti, none of the bomber’s open windows and gun turrets could be spared for a camera, so crews rigged up an alternative.”They could not photograph from the side (of the bomber) because of the gun emplacements,” he said. Instead, the crew “attached a mirror out of the back of the plane. It was a front surface mirror, like on a car.” “When they mounted the camera inside the plane to photograph the mirror’s reflection, things were in reverse,” he said. The image that was later widely reproduced, and appeared on the Stars and Stripes front page, “is completely wrong,” he said. When he punched his bomber out of the black smoke about 150 feet off the ground, he saw the smokestacks dangerously close on his right hand side. In photographs, the bomber should appear to the right of the smokestacks. But even the National Archives version of the photograph is flipped, and the bomber is on the left of the smokestacks. It’s something Sternfels hopes they will correct for history’s sake. “One side is correct,” he said. “But the other side is preferred in reprints.” In his book on Operation Tidal Wave, “Burning Hitler’s Black Gold,” published with co-author Frank Way in 2000, the photo is correct.