On this day in aviation history, December 25, 1958, a Soviet interceptor made its first flight—the Sukhoi Su-11. Developed by the Sukhoi Design Bureau under Pavel Sukhoi, the Su-11 promised to be an improved version of the Su-9 interceptor, but despite a small production, it was overshadowed by later aircraft and remains a little-known aircraft of the Cold War.

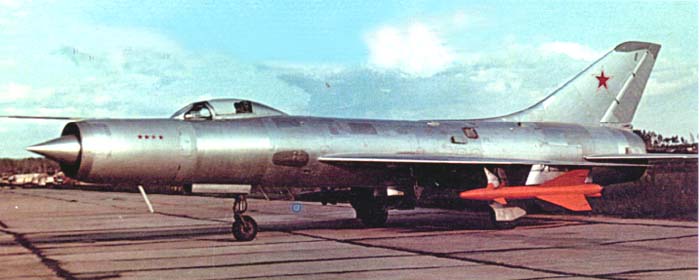

Not to be confused with a 1940s prototype that never entered operational service, the Sukhoi Su-11 was a development of the Su-9 delta wing interceptor (codenamed by NATO as the ‘Fishpot’), a contemporary of the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 (NATO codename ‘Fishbed’). The Su-11 inherited the Su-9’s delta wing, swept tailplanes, and cigar-shaped fuselage, along with the Su-9’s nose intake design. Where it differed from the Su-9 was in the lengthening of the aircraft’s nose, primarily to accommodate a new radar unit called the ‘Oryol’ (‘Eagle’ in English (NATO gave this radar set the reporting name ‘Skip Spin’)). The Su-11, which NATO codenamed the ‘Fishpot-C’, also had an upgraded version of the Lyulka AL-7 turbojet engine compared to the one that powered the Su-9. This variant gave the Su-11 greater afterburning thrust for a better climb rate and high-altitude performance over the Su-9. Besides the lengthened nose and larger radar unit, the most distinguishing feature between the Su-9 and the Su-11 were the Su-11’s external fuel pipes mounted on the aft of the fuselage. The aircraft was armed with two Kaliningrad K-8 medium-range air-to-air missiles.

It was intended that the Su-11 should replace the Su-9, and it was ordered for mass production. In 1961, the Su-11 was shown to the public for the first time at the annual Soviet Air Fleet Day aerial parade held at Tushino Airfield, just outside Moscow. But just as production began in the state aircraft plants, the first production model Su-11 was destroyed in a fatal accident on October 31, 1961, when its engine failed during a test flight over Moscow. At this point, some in the upper hierarchy of Soviet military aviation worried about future accidents, while at the same time, Alexander Yakovlev, head of the Yakovlev Design Bureau, was pushing for the development of his own interceptor project, the twin-engine Yak-28P. At the same time, the Sukhoi Design Bureau had already foreseen the need to replace the Su-11 itself and had developed the aircraft that would become the Su-15 interceptor (NATO reporting name: Flagon).

What’s more, rapid advances in jet aircraft and airborne radar units, combined with changes in NATO bomber strategy from high-altitude attacks to low-level, high-speed bombing runs meant that the Soviets now had to deal with the potential of both high-altitude and low-level attacks, while the Su-11 was designed specifically for high-altitude interception. Another factor to consider was the fact that the Su-11’s nose-mounted Oryol radar unit, while more powerful than the Su-9’s radar, was still reliant on ground-controlled interception (GCI) to vector it to targets, and it was becoming apparent that Soviet interceptors should also be powerful enough not only to carry larger onboard radar systems but also more weaponry than the Su-11 was capable of sortieing out with.

In the end, the Kremlin decided to select the Su-15 and Yak-28 over further development of the Su-11, and production ended after only 108 examples were produced. The aircraft that were built, however, would remain in service with the Soviet Air Force to replace older interceptor aircraft. The Su-11s would not be exported outside the USSR, with the last examples being retired in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Today, at least one example, s/n 0115307, has been preserved on outdoor display at the Central Air Force Museum in Monino, located just east of Moscow.

The Sukhoi Su-11 may not have been a very successful fighter, but that was in large part due to circumstances outside the control of its designers. As such, the Su-11 became one of many combat aircraft on both sides of the Iron Curtain to have been superseded by the introduction of newer designs shortly after they themselves were introduced into operational service.

Today in Aviation History is a series highlighting the achievements, innovations, and milestones that have shaped the skies. All the previous anniversaries are available HERE