From an original article by Zellie Orr

In the spring of 1949, the 332nd Fighter Group— the unit of the Tuskegee Airmen— arrived in Las Vegas for the inaugural Continental Air Gunnery Meet, which was the U.S. Air Force’s equivalent to the U.S. Navy’s “Top Gun” school that would begin 20 years later. This all-Black fighter and bomber group, which trained in Tuskegee, Alabama, was among the most decorated squadrons in the segregated military during World War II. After working tirelessly to keep the 332nd planes operational during the competition, a few members of the ground crew decided to unwind at the renowned Flamingo Hotel. However, they were stopped by security guards at the entrance and ordered to leave, being told the casino was for “Whites only.”

Such treatment was common in 1949. Despite risking their lives for their country in World War II, many places across the nation denied entry to Black servicemen.

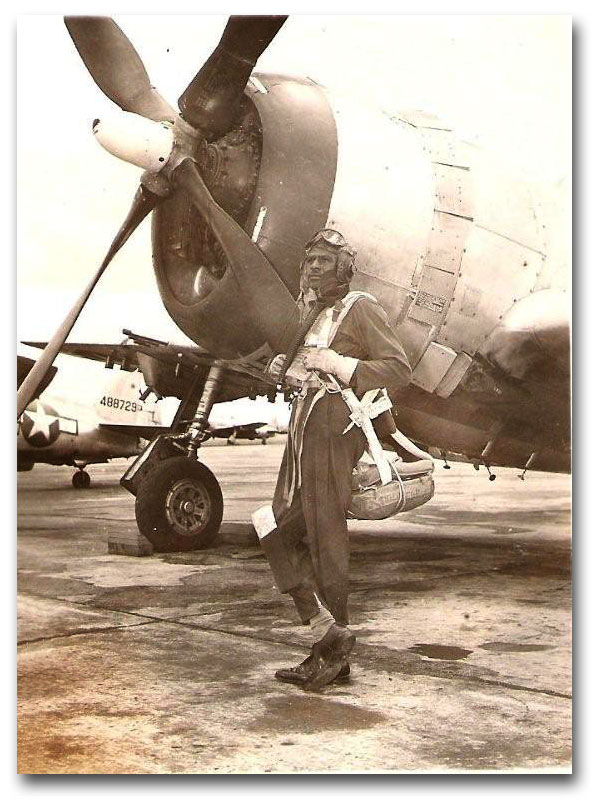

For 1st Lt. Harry Stewart—who flew a P-51 Mustang and scored three aerial “kills” against German planes in the war—and the rest of the 332nd’s team, the first gunnery meet was an opportunity to prove themselves against other Air Force aces. Their mission was to disprove the prevalent belief that Black aviators were not as capable as White ones.

“Having gone into the service under segregated conditions, we would hear statements like, ‘These guys really don’t know how to fly’ or ‘They’re not mentally equipped to do this,’” said Stewart, now 97, in an interview from his home in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. “This was a chance for us to show what we could do among the best of the best.”

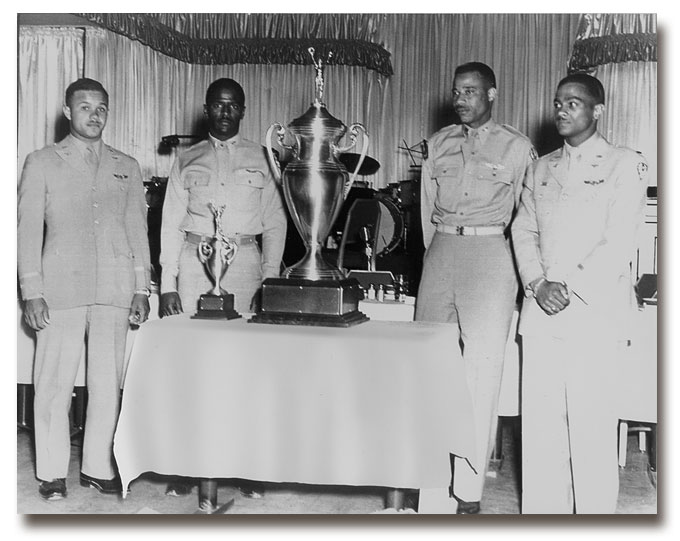

And they did just that. The Tuskegee Airmen—Stewart, Capt. Alva Temple, 1st Lt. James Harvey III, and alternate 1st Lt. Halbert Alexander—achieved victory, defeating teams from other Air Force fighter groups to claim the first trophy in the propeller class. They excelled in aerial gunnery, skip and dive bombing, strafing, and rocket firing at the meet, which also included a separate competition for jet fighter groups.

However, their achievement was forgotten—either accidentally or intentionally—for seven decades. While the jet winners, the 4th Fighter Group, were recorded in Air Force almanacs, the propeller winners of the first competition were listed as “unknown.”

That oversight was rectified in July 2023, when a plaque naming the four Black pilots was installed at the U.S. Air Force Weapons School at Nellis Air Force Base in Las Vegas. It acknowledges their achievement of earning “Top Team Honors” at the fighter gunnery meet in 1949.

Present for the presentation on January 11, 2023 was Harvey, who had urged the Air Force to recognize his team’s victory. He was supported in his efforts by Wish of a Lifetime, a project of AARP. “We weren’t supposed to be able to fly aircraft, we weren’t supposed to be able to win this competition, but we did and we were the best,” Harvey said in a statement released by the Air Force after the ceremony.

Part of the confusion over the lack of recognition stemmed from a missing trophy. The original silver cup used for the 1949 and 1950 competitions bore the names of all the winners, but it disappeared, and its whereabouts remained unknown for 55 years.

In 2005, researcher and historian Zellie Rainey Orr located the trophy while trying to honor a Tuskegee airman from her hometown of Indianola, Mississippi. She discovered that the missing award was in storage at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

“I made a few calls and found it in a box at the museum,” she said in an interview. “It took much longer for the Air Force to display the trophy after they realized what they had.” Orr later recounted her journey to find the award and have it exhibited in her 2011 book “Heroes in War, Heroes at Home: First Top Guns.”

For Harry Stewart, who received an honorable discharge in 1950 and later retired from the reserves as a lieutenant colonel, finally being honored as part of the first class of “Top Gun” pilots in the Air Force is a thrilling experience. He recalls flying the F-47N—a later version of the P-47 Thunderbolt, one of the most successful fighter planes in World War II—in the competition and helping his team outscore the other fighter groups using F-51s, the reconfigured Mustang, and F-82s, the unique “twin” Mustang.

Stewart also remembers the celebration after his team was judged to be the Air Force’s premier fighter pilots. He and his fellow pilots had their photo taken with the trophy bearing their names at an awards banquet held at the Flamingo Hotel. This time, there were no security guards preventing them from entering.

“I’m very grateful and feel very good the Air Force is recognizing our accomplishment,” said Stewart, who published “Soaring to Glory: A Tuskegee Airman’s Firsthand Account of World War II” with Philip Handleman in 2019. “It gives me a great deal of satisfaction to have the country and the world know that the abilities and performance of the Tuskegee Airmen were among the best of the best.”

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.