Friday Feature: We promise this story will bring a lump to your throat… so please read to the end…

Chris Demarest is an author and illustrator of over one hundred titles. The New York Times chose his book, FIREFIGHTERS A to Z as a “Best Book” in 2000. More recently, his focus has shifted toward documenting people in unusual professions. For the book MAYDAY! MAYDAY!: A Coast Guard Rescue Demarest flew regularly over the course of a year with the US Coast Guard out of Cape Cod. Two years later, he flew with the Hurricane Hunters into Hurricane Ivan researching HURRICANE HUNTERS: Riders On The Storm. His work has now expanded beyond children’s books. In 2006, the US Coast Guard sent him (as an official Coast Guard artist) to the Persian Gulf to live with, and document crew work guarding the oil platforms off the coast of Iraq. Last year was spent flying with DHART, the local trauma center medical evacuation team out of Dartmouth=Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, NH. An article he wrote on that experience appeared in Dartmouth Medicine magazine (summer ’08). He later spent time at the children’s ward chronicling patient and medical staff work.

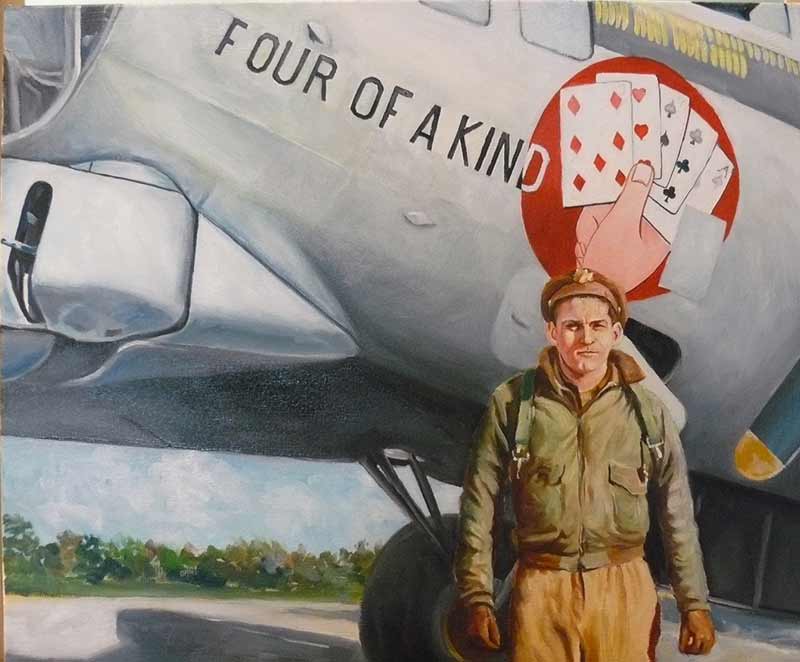

In 2011 he began a journey which continues today. Sparked by the black and white image of a WWII fighter pilot, he began working on a series of portraits depicting people who contributed both at war and on the home front. Setting up at the Women’s Memorial near the gates to Arlington National Cemetery, he worked for two years, stockpiling over seventy portraits. In May 2013, he began a road tour in his hometown of Amherst MA which went from the promise of one month to a plea to stay as long as possible. That project ran the entire summer. In the fall he heads to Texas and will be wintering in California with the number of venues to visit growing.

WarbirdsNews had the opportunity to sit down with Cris and discuss his work, and here are the results of that meeting.

‘Serendipity’. That’s the word to describe what started and has led to a three year and growing experience. Early in 2011, having recently moved from New Hampshire to Washington, DC, I was at a point in my professional career as a children’s book author and illustrator, where my passion for the work and the declining publishing market was pushing me away. But the question was “Now what?” Children’s publishing was all I had known for over thirty years.

The answer came one evening when, invited to a couple’s house in Bethesda, Maryland for dinner, the husband took me to the den and proudly showed off a photograph of his father taken in World War Two. This 8×10 black and white image showed a nineteen year old kid standing on a wheel of his P-47 fighter plane, cocky as all get-out. A few weeks later I found myself back at the house. Once inside I returned to the den, removed the framed photo from the wall and declared to the son: “I have to paint this.”

That declaration turned into a commission for this man to give his father, the young P-47 pilot, Griff Holland, for his 88th birthday. It soon became clear to me that I was onto something. My father, a C-47 pilot flying the infamous “Hump” -India over the Himalayan Mountains into China, had died two decades before, but I had in my mind’s eye, the photo of him I remembered from my youth: a young man, sunglasses on, sitting in the pilot’s seat, intently looking over his shoulder into the camera lens.

To get further images, I used social media to reach out to former high school friends for their parents war time photos. Within two days of emailing the Women’s Memorial at nearby Arlington National Cemetery a request to use their facility, I received a favorable reply. The catch to my request was an unusual one, something I’d never done before: work in public. By May 1st, 2011, I was set up and painting.

Working with the memorial’s curator Britta Granrud, I chose multiple images of women in service. With each portrait, a story would accompany it. My goal was to paint both men and women so the public could get to better idea of who these people were. My instincts for working on-site proved spot on. The public coming through and seeing these paintings, often stayed long enough to talk about their own experiences or from the off-spring, personal stories of a parent. In too many cases, it was the oft-repeated: “He never talked about it.”

Shortly after setting up and with Griff Holland’s blessing, I borrowed his portrait to help fill out my meager collection of a dozen paintings. I had gotten to know Griff over the previous months and wanted him to visit the memorial and see his portrait hanging in the growing collection of other WW II portraits. Griff, originally from Maryland, has that Chuck Yeager drawl and swagger. Walking down the hallway of the Women’s Memorial, he blurted out “Too distracting,” at the many photos of attractive women in service, not to mention the mannequins wearing size 4 uniforms. Once a fighter jock, always a fighter jock.

I had also known, from his son, Griff’s feelings toward the Japanese. Many war wounds never healed. He had flown in the Pacific theater. As we approached the gallery, I spotted three people in front of his portrait. I made a beeline for them and pointing to the image of young Griff, I asked if they would like to meet the man. Enthusiastically a mother and her teenage kids said “yes!” They were Japanese Americans and I was committed.

Waving Griff over, he and the mother introduced themselves and started talking. There was still the swagger of a young fighter jock but polite in his conversation. Listening intently, my eyes moved to the woman’s hand subtly reaching toward her purse. Her hand briefly disappearing, emerged holding a small object. She showed it to me. It was an origami heart made from a dollar bill, wrapped around a quarter. Turning to Griff, she offered the heart with the words: “Mr. Holland, she began.”I’d like to thank you for your service.” Silence as Griff took this gift. I was stunned watching Griff’s reaction. Confusion, pain, relief, raced across his face. But within seconds a smile appeared, thanking her. I had the presence of mind to take a photo of the mother and Griff, both smiling in front of his portrait, him holding the heart.

Five minutes later, as Griff and I were strolling back toward the front entrance, he whispered: “All these decades I’ve hated the Japanese.” He reached into his dress shirt pocket and pulling out the origami heart, held it in both hands like a fragile bird’s egg. “I have to go home and frame this.” I was shaking as I watched this man through the plate glass windows, slowly walking away. Serendipity re-entered the picture.

For two years I painted over seventy portraits, gathered stories, listened to many tales and with the desire to share all this, hit the road, eighteen months of venues lined up. I had no funding, no support. But it was a mission that felt right.

My first stop was my hometown of Amherst Massachusetts, exactly two years to the day I had started in Virginia. Six portraits were of Amherst residents, now, like my father, all gone. Set up in the town library, I remembered thinking as I walked through the front door that first day: “This will never work.” Two years at a military memorial drew nothing but support. What would a college town, a haven for peace protests going back to my days in college during the Vietnam war, see in this exhibit?`

What happened was something completely unexpected. Set up in the foyer, people started stopping by, pulling up chairs and talking at length. I quickly realized, unlike tourists who pass through an institution, these were townspeople who use the library on an ongoing basis. They had the time to talk. They wanted to talk. I began writing blogs to remember what had happened. Ten days into what was supposed to be a one-month exhibit, Sharon Sharry, the library director told me bluntly: “You’re not going anywhere! You have brought life blood like we’ve never seen before.” I stayed four months.

There were funny stories and sad stories. There were revelations of long-hidden wartime letters, newly discovered in attics. A 93 year old B-17 bombardier called me one day to see if he could bring in his wartime photo album. Jim and I sat for two hours looking through his book. “I haven’t looked at this in many years,” he said, adding,”Not since my wife died.” I referred to my work space as that of Lucy from the Peanuts comic strip, set up on the sidewalk with crate and sign reading “Psychiatrist in. 5 cents.” People wanted to talk. Not a day went by without someone sitting down and sharing their story.

From Amherst it was a month at a Soldier’s Home in Holyoke Massachusetts before turning south to the little city of Boerne Texas, just north of San Antonio. It was yet another library, a last minute replacement. ‘Serendipity’. Again more stories came through the doors as more people took the time to sit and talk. 86 year old Ellen I met shortly before leaving for California. She had grown up in Vermont where I had lived as an adult for a few years. She became a Rosie-the-Riveter and brought in her album to share. This pixie of a redhead, seen kissing numerous soldiers, sailors and occasional airman, was doing her duty, as was her defense. “I was only kissing the uniform,” she coyly replied to my observation of a lot of coupling going on.

More stories continued. More blogs written. What I was realizing as I drove to California where I would be setting up for several months at the Palm Springs Air Museum, was that this tour had become a journey. It was not only about people’s portraits and their stories. It was especially about the people I was meeting along the way.

One fall weekend, while at a WW II event in the eastern part of Massachusetts, set up with paints, easel and displayed portraits, I met a man in his eighties whose first words to me were: “I never talk about ‘it’. If I do,” he continued.” I tear up.” now pointing to his glistening left eye. But for fifteen minutes Basil LeBlanc talked about his experience as a frightened young man, part of the Canadian Grenadier Guard tank division fighting through Europe. “I was a replacement for a guy killed,” Basil shared. “They called me “Kid” because they didn’t want to know my name and get close to me. We were all cannon fodder,” he concluded.

When his sons found him, we briefly continued the conversation. Finally turning to his adult children, he proclaimed: “I have said more to this man than I’ve ever said to anyone, including your mother.” Pausing, he added: “And I don’t know why.” I slipped my business card into one of his son’s hands with the whispered request to send me a photo from the war of his dad.

A week later, Basil himself emailed me. In so many words he thanked me for the honor. He wrote: “There are many books that have been written about WWII… and will be. But those are just words. What you’re doing is capturing the look and feel as I remember it.” Those were heartening words.

Fast forward to April of this past spring. I receive an email from a Lt. Col (retired) Canadian Grenadier Guard telling me of his surprise at finding on display at the Palm Springs Air Museum, a portrait of one of his own. Basil LeBlanc’s printed out story mentions his lost medals. Asked to forward this email to Mr. LeBlanc, he states that the Canadian government is now ready to reissue his medals. For a man who didn’t want to think about ‘it’, the past was coming back in a big way.

It took three days for Basil to respond to my email. He wrote that he hadn’t slept for two nights, adding that he needed, to talk to this former commander and pour out his feelings. A week later, Basil emailed news that they two men had spoken. “I have been asked to come to Montreal to receive these medals,” he began. “I don’t know why you and I met last fall. I don’t know why you chose to paint my portrait. But what I do know is that you have to be there in Montreal,” he concluded. I made my promise right then to meet up again. ‘Serendipity’. This is what this tour is about. This is a journey of discovery I plan on continuing touring with requests into the year 2016.