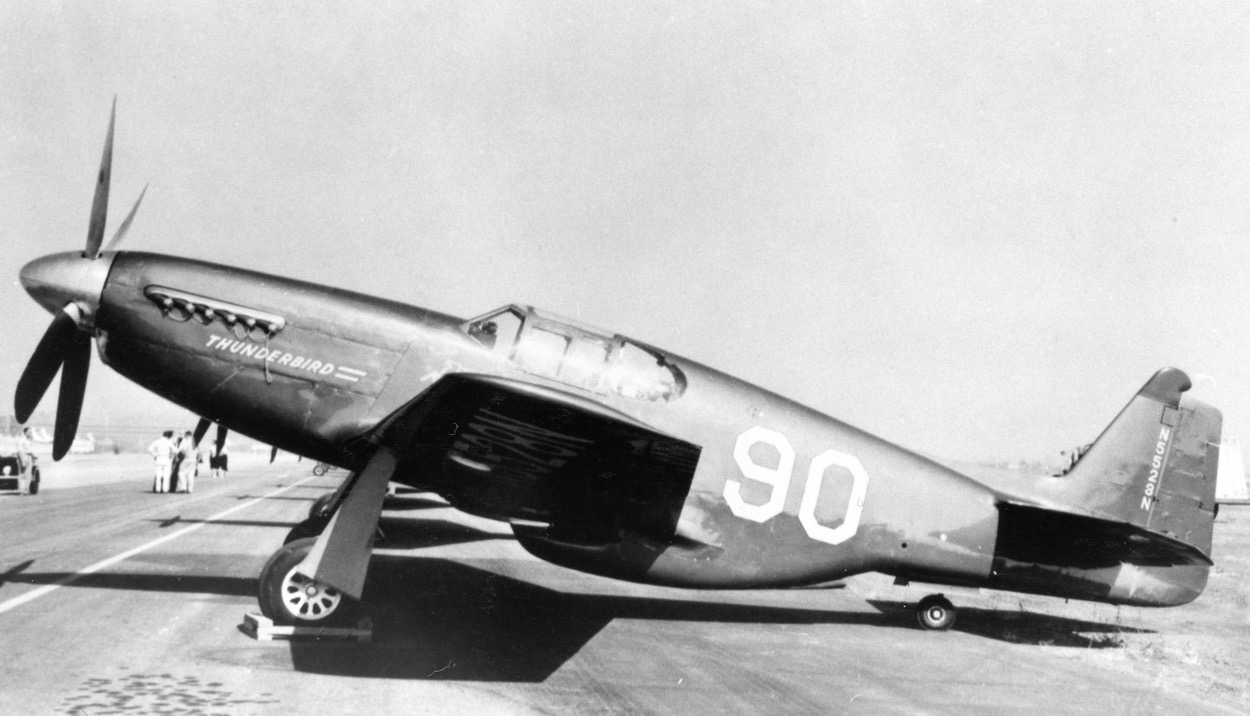

Over the past several years, aviation historian Chuck Cravens has brought us regular updates regarding ongoing restoration projects at AirCorps Aviation in Bemidji, Minnesota. Many of the aircraft involved have been for the fabulous Dakota Territory Air Museum, and such is the case for this particular story about the resurrection of a long-lost, legendary racing Mustang which dates to the post-war Cleveland National Air Races. The original constructors of this race plane built the airframe up from the components of three different Mustangs, but did not record their serial numbers. They listed it as a P-51C with the FAA, with the registration being N5528N. During her racing career, the Mustang bore the names Thunderbird, and later, Mr.Alex, so with the lack of a definitive airframe serial number, we will refer to it henceforth simply as Thunderbird/Mr.Alex. This current episode is Craven’s fifth installment of that aircraft’s remarkable story and its journey back to flight…

Work on the cowling, fuselage, and wings all progressed over the last few weeks. The cockpit components and cockpit enclosure were areas which also received attention.

Cockpit Enclosure

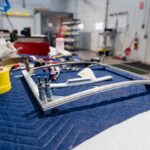

Fitting the windshield assembly and the rest of the cockpit enclosure is an exacting process. The aluminum frame structure needs to be fitted, and each window has to be trimmed precisely.

Fuselage

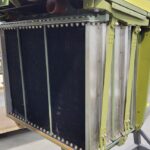

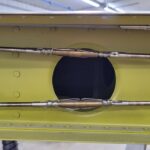

Work on components for the cockpit has progressed nicely since the last update. Some firewall-forward engine accessories were also installed. The air scoop area is under preparation and the radiator is now installed; several related skin sections were also trimmed and fitted into place.

Cowling

Mike expended considerable effort in fitting skin sections to the cowling. Thunderbird’s cowling featured several deviations from a standard P-51C configuration.

Fédération Aéronautique Internationale World Air Sports Federation)

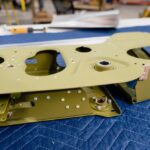

Wing

Thunderbird’s wings have a few differences to those of a stock military Mustang, most notably in their lack of armament bays and gun ports.

Historical Highlights of the Bendix Trophy Race

Thunderbird’s fame comes in large part from its victory in the 1949 Bendix Trophy and its all-time, propellor-driven average race speed record of 470.136 mph. 1949 also marked the final running of the propellor-driven Bendix Trophy race, making Thunderbird its ultimate winner.

The Vincent Bendix race originated with a 1931 meeting in the club car of the New York Central Railroad’s premier passenger train – the Commodore Vanderbilt. Vincent Bendix was a famous and very successful industrialist and inventor. His company manufactured everything from automobile brakes and starters, to avionics and pressure carburetors for airplanes.

Clifford Henderson, the originator and promoter for the National Air Races, approached Bendix to propose an annual, free-for-all, cross-country air race. Henderson’s sales pitch involved the proposed race providing a goal for airplane designers, builders, and pilots to “really get down to business.” By this, Henderson implied that the competition would boost the design of faster, more reliable, and more durable aircraft. Henderson felt that the Bendix name had a magic ring to it, fostering an image of speed, reliability, and progress. Sponsoring the race would also help Bendix promote his aviation products.

Henderson showed Bendix a preliminary drawing of a trophy proposed for the race, but it failed to impress. Bendix thought that it resembled an ordinary loving cup, and told Henderson to return only when he’d designed a more impressive trophy.1

For a far more comprehensive history of the Bendix Trophy Race, please see Don Dwiggins’ book, They Flew the Bendix Race, footnoted below.

1Don Dwiggins, They Flew the Bendix Race, J.B. Lippincott Company, New York, 1965, p.14-15

Henderson commissioned a new trophy from the artist Walter A. Sinz, who sculpted the design and then cast it.

Vincent Bendix must have liked the new 100-pound bronze trophy, because he agreed to sponsor the cross-country race with a contribution of $15,000 which had to be matched by the Cleveland Air Race Commission.

The legendary Jimmy Doolittle became the competition’s first winner, flying the Laird Super Solution at an average 223.058 mph, during the Bendix Trophy Race of 1931. Henderson’s vision to encourage aircraft designers/builders to strive for more speed and reliability worked. The nature of the long, cross-country race demanded significant reliability for an aircraft even to finish, and each iteration of the race saw developments which usually increased the average race speed.

The 1935 Bendix featured the first (and only) racer specifically created for the race. Designed by famed aeronautical engineer Benny Howard, the sleek high-winged monoplane was designated as the Howard DGA-6, although its nickname, Mr. Mulligan, is far better known.

Howard’s philosophy was for Mr. Mulligan to fly the entire Bendix race, nonstop, at high altitude.

Eliminating the fuel stops which each previous Bendix racer had to make saved a great deal of time, and the strategy proved successful; Howard finished first in 1935, ahead of Roscoe Turner. Howard even went on to win the Thompson closed-course pylon race on the following day.

Variants of the Seversky SEV-2S won the three Bendix races run between 1937 and the onset of WWII, which saw the suspension of air racing. Jackie Cochran won the 1938 event in a Seversky AP-7, an improved civilian version of the Army Air Corps’ P-35. Jackie averaged 249.774 mph during that race. She later went on to feature in Thunderbird’s history too.

The post-war races took advantage of the accelerated improvements in aircraft design and technology which were the result of the all-out war effort. P-51 Mustangs won each of the propellor division Bendix Trophy’s from 1946, when racing resumed, through the last propellor-driven race in 1949. Paul Mantz won the race in 1946, 47, and 48, but Joe DeBona took the 1949 Bendix Trophy in Thunderbird, with a record speed of 470.136 mph, a record which still stands since it was the final Bendix race to include a propellor division.

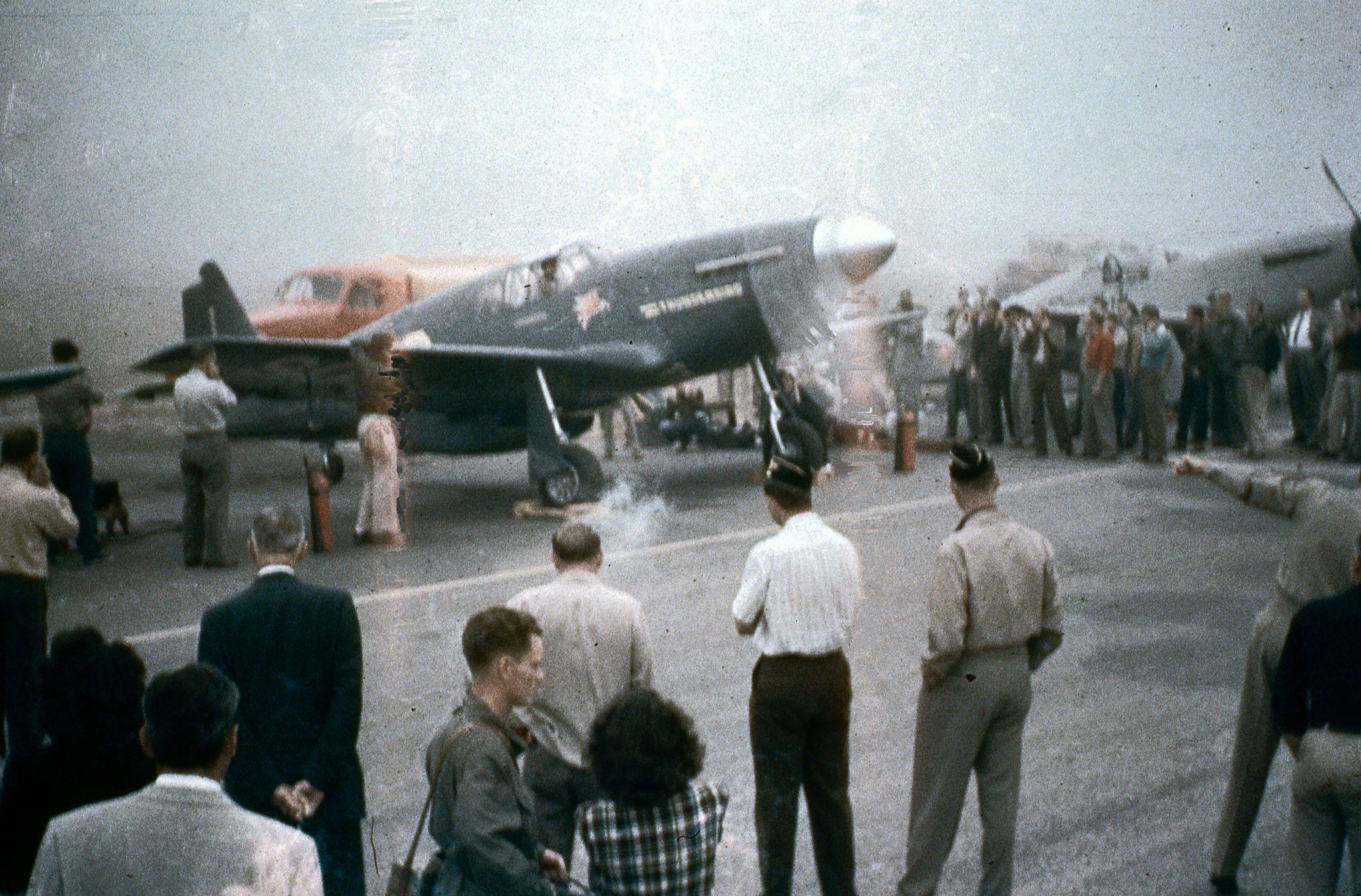

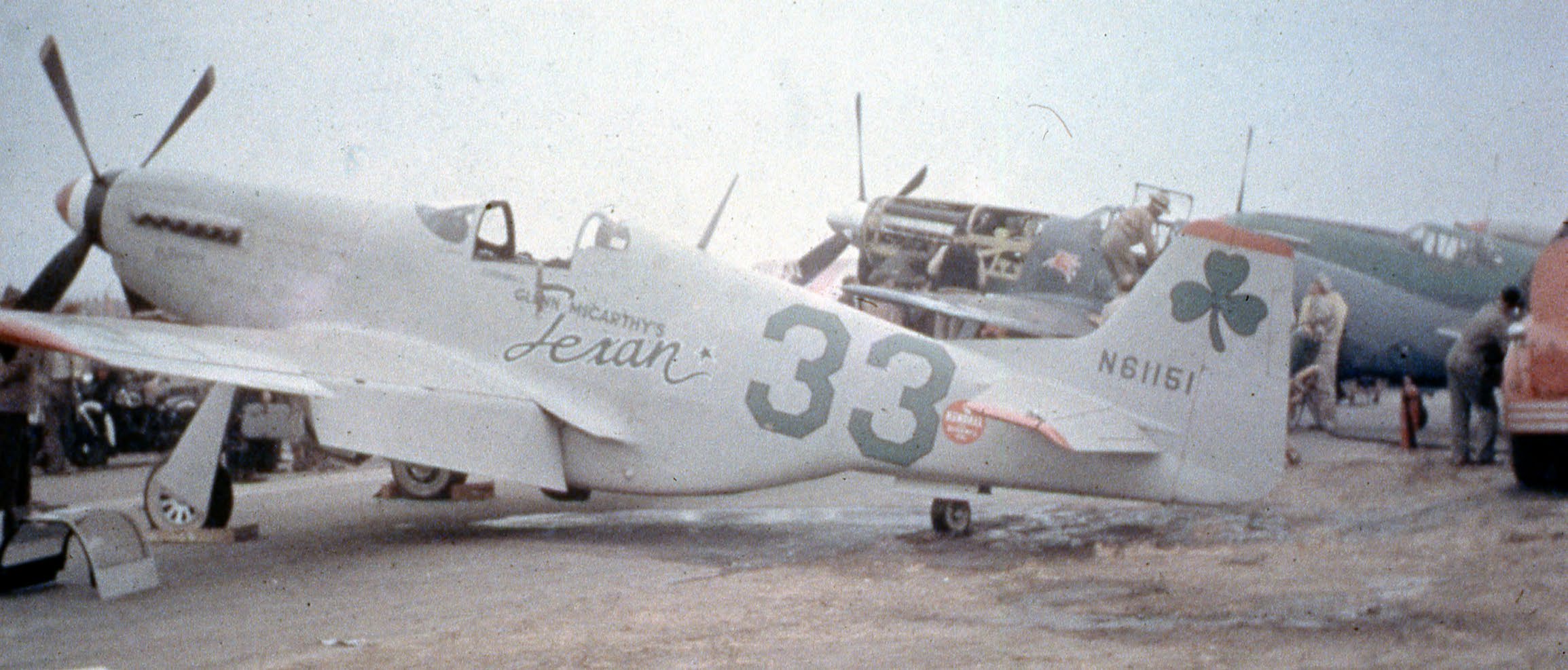

One of the Mustangs sponsored by oilman Glenn McCarthy appears on the right side of the above photo. That aircraft was Buttonpuss, the nickname which the aircraft’s pilot, Edmund Lunken, gave his first wife, Dorothy. Lunken finished in 4th place with an average speed of 441.594mph.

In the first color photo, there is an odd-looking device atop Thunderbird’s vertical fin, which is depicted more clearly in the image below.

From biplanes at 223 mph to Mustangs at 470 mph, the Bendix race showcased the aeronautical engineering progress that took place from 1931 through 1949.

Special thanks must go to the air racing historians/authors A.Kevin Grantham and Tim Weinschenker, as well as the author Mark Phillips for their help in providing images and proper credits for this segment on the Bendix Trophy air races.

And that’s all for this exciting news about the resurrection of Thunderbird. We will present further updates as this famous racing aircraft returns to her former glory. Many thanks to Chuck Cravens and everyone at AirCorps Aviation and the Dakota Territory Air Museum for their help in making this article possible.

Related Articles

Richard Mallory Allnutt's aviation passion ignited at the 1974 Farnborough Airshow. Raised in 1970s Britain, he was immersed in WWII aviation lore. Moving to Washington DC, he frequented the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum, meeting aviation legends.

After grad school, Richard worked for Lockheed-Martin but stayed devoted to aviation, volunteering at museums and honing his photography skills. In 2013, he became the founding editor of Warbirds News, now Vintage Aviation News. With around 800 articles written, he focuses on supporting grassroots aviation groups.

Richard values the connections made in the aviation community and is proud to help grow Vintage Aviation News.

What is the advantage of the D model wing over the C model? I thought the B’s and C’s had a thinner wing which gave it a slightly faster speed over the D models. Was it fuel capacity?

That’s a good question Marc, I will ask them and see what they say. Many thanks for writing in!

Hi Marc… well, as it turns out, the answer to your question about the wing choice is covered in the first of Chuck Craven’s articles about Thunderbird. Here is the quote which will offer some insight into their thinking…

“One of the aspects affecting this choice to use a D-model wing relates to both safety and handling qualities. The later model wing has more robust and reliable landing gear and gear door systems. The B/C wing’s clamshell doors were lighter and had a single uplock, while the D gear doors have multiple locks which make cycling the gear more reliable. Additionally, there are documented instances of B/C doors tearing off in high speed dives, so North American re-engineered an updated system for the D model.

Interestingly, the early model clamshell doors on the original Thunderbird may have been what caused the aircraft to crash in June of 1955 when they closed out of sequence, jamming the main landing gear. The owner at the time, Joe Cook, elected to bail out rather than risk a landing in the wet-winged Mustang with the gear now protruding from the airframe.

In addition to improved gear doors, the D model wing also has stronger and more effective ailerons. A seal added to the aileron leading edges reduced stick pressure during hard maneuvering.”