Located at Hill Air Force Base, Utah, the Hill Aerospace Museum is one of the largest museums dedicated to aircraft of the United States Air Force (USAF) in the western United States. While we have covered one of the latest developments at the museum, the opening of the L.S. Skaggs Gallery (NEW GALLERY OPENS AT HILL AEROSPACE MUSEUM (vintageaviationnews.com)), two more prior achievements that deserve to be celebrated are the recoveries of a Lockheed P-38J Lightning and a rare Consolidated B-24D Liberator bomber from the wind-swept tundras of uninhabited volcanic islands in the Aleutian Island chain. These two aircraft represent two individual stories of determination, both of the aircrews, and of the men who set out to recover these priceless aircraft.

The first of the Aleutian recoveries for the Hill Aerospace Museum was Lockheed P-38J Lightning, United States Army Air Force (USAAF) serial number (s/n) 42-67638. This aircraft rolled off the Lockheed assembly line in Burbank, California, with the construction number 422-2149, and was delivered to the USAAF on October 23, 1943. By May 1944, the aircraft was assigned to the 54th Fighter Squadron (FS)/ 343rd Fighter Group (FG) with squadron number 85 a remote airfield on Alexai Point, Attu Island. Attu had previously been among the two islands in the Aleutians occupied by the Japanese military (the other being Kiska) that had been retaken from the Japanese in 1943. Now that the islands were devoid of Japanese occupiers, American fighters in the form of P-38s and P-40s set out on patrols to find Japanese surface and air vessels, with the P-38s even escorting B-24 Liberators on bombing raids to the Kuril Islands (now part of the Russian Federation) and intercepting Japanese Fu-Go balloon bombs that flew at 30,000 to 37,000 feet directly above Attu on their way from Japan to North America.

On February 2, 1945, ‘638 set off on a two hour test flight to evaluate the aircraft’s performance after a 50-hour inspection. At the controls was Lt. Arthur W. Kidder, Jr. from Colorado, who had previously flown 54 combat missions over Italy with the 82nd FG, scoring four aerial victories in Europe before making this routine flight. Upon completing his mission, Kidder requested a clearance to land over the radio, and received a vector heading and told by the controller he was only 15 miles from the base. However, when Kidder broke through the clouds at 1,500 feet, all he could see was freezing water below him. When he attempted to contact the tower again, he discovered that the antenna on his primary radio was gone, having iced over during his descent through the overcast and snapped off. Kidder climbed back through the clouds to transmit through a backup line-of-sight radio, but no reply came. Thus, he began flying a rectangular search pattern of diving below the clouds to look for the base, then climbing back up to transmit through the backup radio, and extending the parameters of the pattern every five minutes. After four hours of fruitless searching and no replies to his transmissions, Lt. Kidder’s fuel tanks were running low, and with no sign of Alexai Point, Kidder knew that he needed to find land to avoid freezing to death in the sea. At last, he found a tiny mountainous island, with a small flat area towards its northwestern most tip that Kidder was confident he could make a wheels-up landing on, and he pointed the Lightning straight for it.

But if he was to make the landing, Kidder had to factor in the relatively smooth underside of the P-38, which was prone to sliding great distances during a belly landing. To shorten his inevitable slide through the tundra grass, he would lower his landing gear, then retract the gear at the last moment, confident that the gear doors would dig into the ground and slow his slide. Sure enough, when Kidder’s P-38 made contact with the ground, the plane only slid about 300 feet through the tall grass of the tundra. At the time of the incident, aircraft number 85 had only 385 hours on its airframe. Soon after emerging from the cockpit, Lt. Kidder saw five figures running towards him and the plane. They turned out to be from a weather outpost for the US Army Air Force’s 11th Weather Squadron, and that they were the only other people on the island. They told Kidder that they came to his position after hearing the crash landing, and that he had landed on Buldir Island, some 100 miles east of Attu. The men immediately sent out a message with their low-powered weather-reporting radio, but because no one expected a report from the weather team at that time, they received no response.

Incredibly, it would take an amateur radio operator out of St. Louis, Missouri to hear the distant distress signals from Buldir Island, who immediately contacted the War Department. With confirmation of the transmissions, a Navy patrol vessel arrived on Buldir to pick up Lt. Kidder and returned him to Attu two days after the incident. The P-38, meanwhile, was stripped of useful parts, such as its armament and radio equipment, then used as a ground target for other P-38s on air-to-ground gunnery training. Once the war ended, however, the Lightning was left to the elements on Buldir Island, and the weather outpost abandoned. The island later became a part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, and the only humans that would return to Buldir would be scientific experts who came to study the local wildlife.

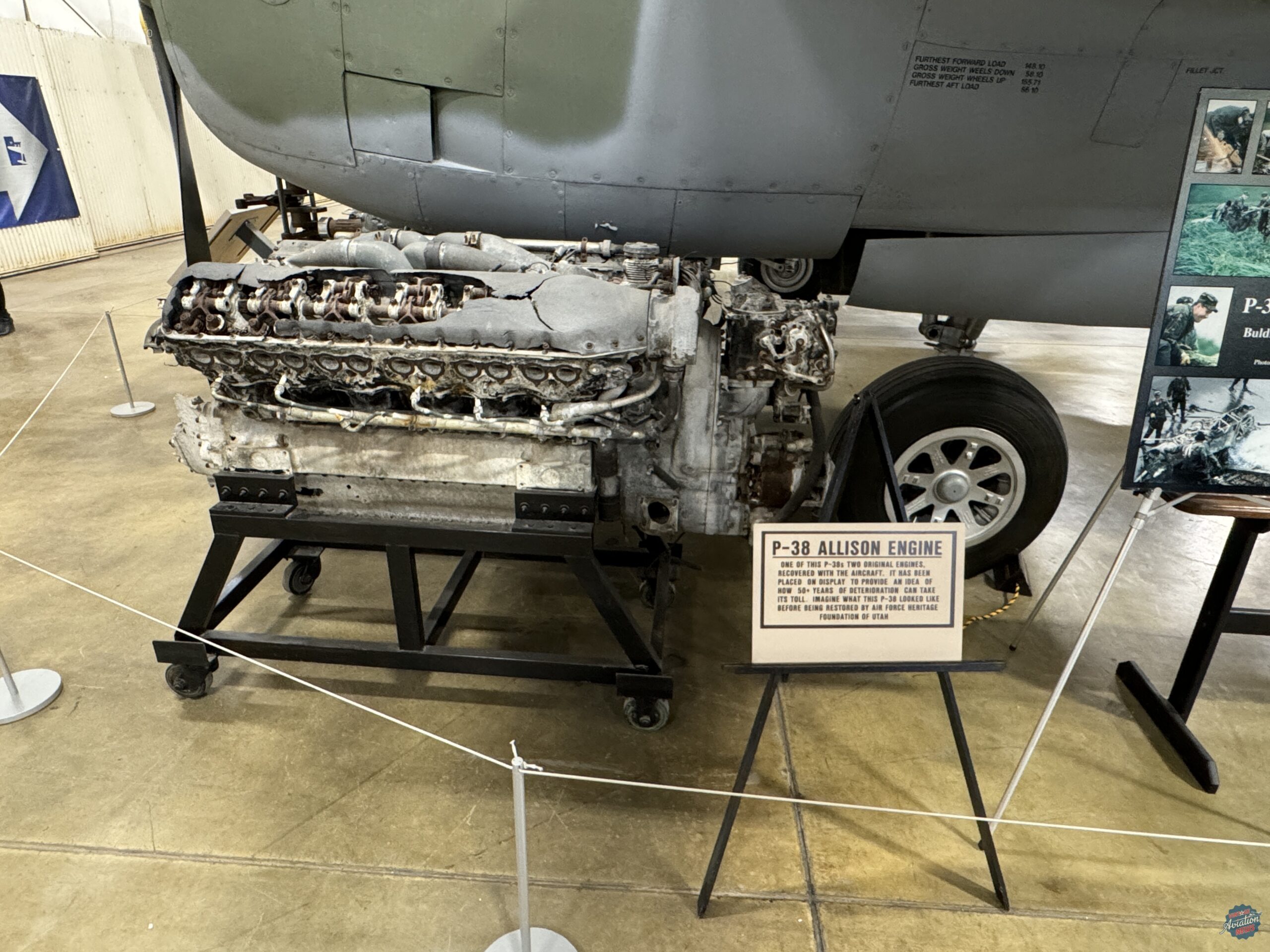

Eventually, the Aerospace Heritage Foundation of Utah, the organization established to provide financial support to the Hill Aerospace Museum, and manage the locating and acquisition of artifacts for the museum. They became interested in finding a P-38, as although there were no Lightnings assigned to Hill during World War II, it was a site for maintaining Allison V-1710 engines. Upon learning of the P-38 resting on Buldir Island, it was determined that ‘638 represented the best candidate for recovery and restoration for display at Hill.

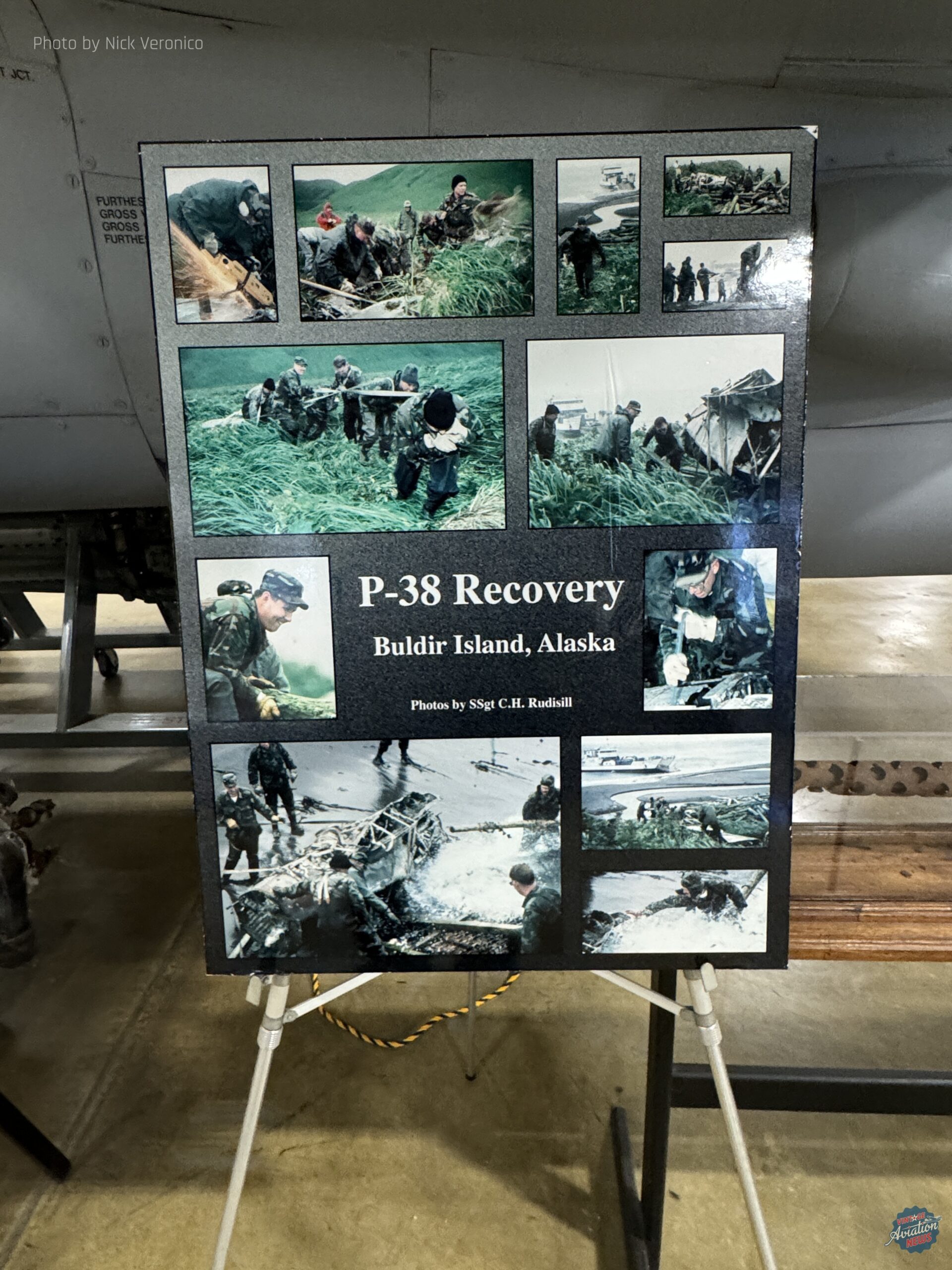

With summer offering the best conditions for recovery team personnel to come and work on Buldir Island, a team of volunteers from the 405th Combat Logistics Support Squadron, stationed at Hill AFB, was brought to Buldir in August of 1994. Also joining them was the plane’s last pilot, Arthur Kidder, who had retired and moved back to Colorado. He had agreed to the Foundation’s invitation to join them on their recovery mission to retrieve the P-38. The recovery team arrived at the crash site with hand and power saws to cut the Lightning into manageable sections to push into cargo pallets and be pulled with a cable and pulleys onto a landing craft-style barge. By October 1994, the remains of the Lightning were brought down to aircraft restorer Ed Kaletta, who established a restoration firm called Kal-Aero at his ranch house in Dulzara, California, just 24 miles southeast of San Diego. But as Kaletta went to work on restoring the Lightning, Hill Aerospace Museum set its eyes on yet another wreck on the wind-swept tundra of the Aleutians, a rare Consolidated B-24D Liberator.

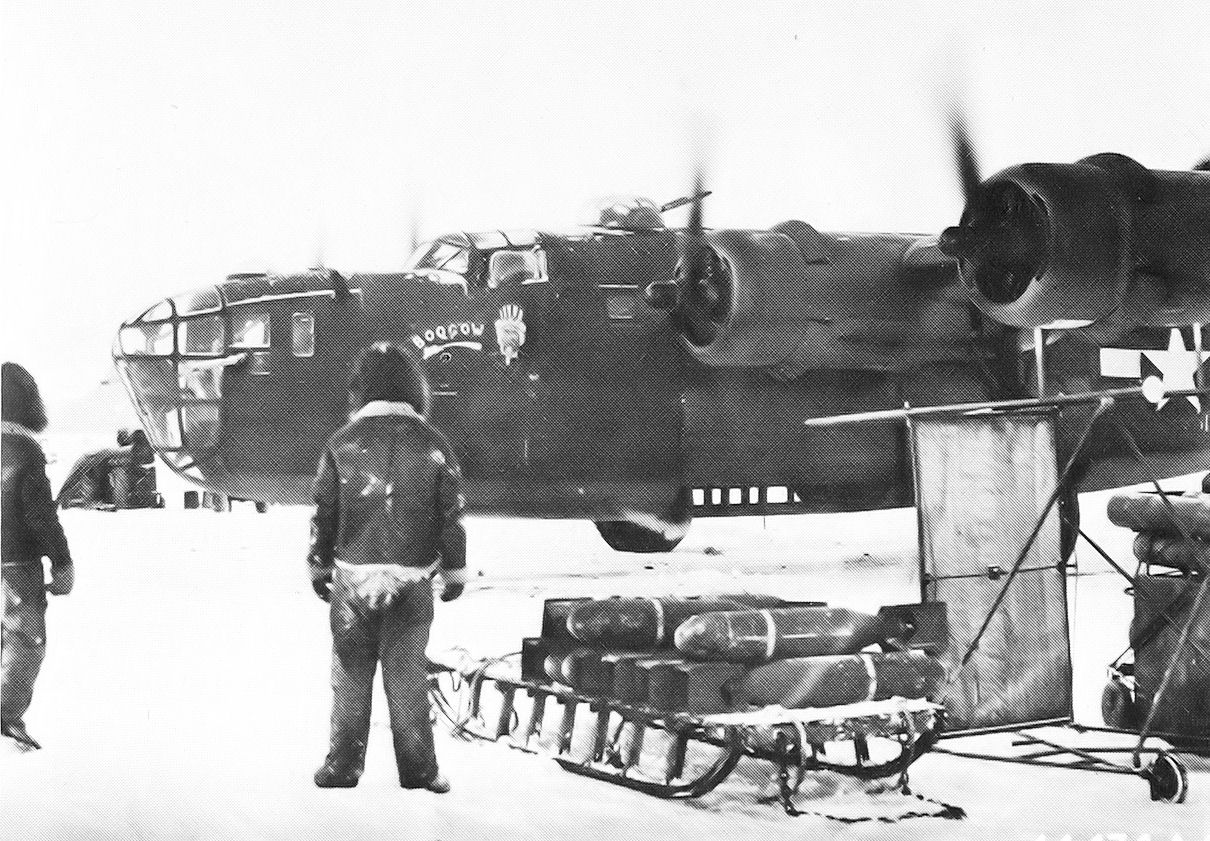

The Liberator the museum sought was B-24D USAAF s/n 41-23908 (c/n 393), which rolled out of Consolidated’s San Diego plant on September 3, 1942, and was accepted by the USAAF six days later. Later that month, the aircraft was flown to Consolidated’s Fort Worth, Texas plant to become one of twenty-one B-24s modified for cold weather operations, before making its way to Elmendorf Army Airfield (AAF) in Anchorage, Alaska through Montana’s Great Falls AAF, which is known today known as Malmstrom AFB.

Upon its arrival in Alaska, ‘908 was assigned to the 21st Bombardment Squadron (BS)/ 28th Bombardment Group (BG), 11th Air Force, and was flown initially from Fort Glenn Army Air Base on Umnak Island before being transferred to an airfield on Adak Island. The B-24s of the 28th BG would fly missions not only to the Japanese-held islands of Kiska and Attu, but would also conduct long-range patrols for Japanese vessels in support of the US Navy’s efforts in the Aleutians. On January 18, 1943, however ‘908 would set out from Adak and never to return. On that day, ‘908 was one of six B-24s that took off at 2:30 pm local time to locate and destroy three Japanese ships headed for Kiska, a 500 mile round trip. At the controls of our subject Liberator was 27 year old Captain (Capt.) Ernest “Pappy” Pruett. The weather along the flight path was poor, described by Pruett as consisting of “…low clouds and heavy fog, a ceiling of only a couple hundred feet.”

Shortly after takeoff, one of the B-24s suffered from engine troubles and was forced to turn back just moments before a second B-24 was forced to head back to Adak. Of these, the first B-24 made a normal landing, but the second one skidded off the runway and smashed into a line of parked P-38s. The four remaining Liberators carried on, but the visibility over Kiska remained poor, and the crews could not find any ships, leading the remaining planes to abort the mission and head for home. During the return flight a pair of B-24s vanished without a trace and presumed lost at sea. Conditions on Adak had worsened, so the final two B-24s, flown by Pruett and Linn Moore, diverted to Cold Bay, some 614 miles to the northeast.

Upon arriving over Cold Bay, with fuel running low Capt. Pruett’s B-24, let down below the ceiling to within 100 feet of the frigid waters of Cold Bay, his crew could not see the runway, and the only approach left to them, had Navy ships anchored in their path. To fly that low would mean running into one of the ships while attempting to lower themselves onto the runway. That left only one alternative; a force landing. Landing in the freezing sea was out of the question, so Pruett decided to make a wheels-up approach on Great Sitkin Island, some 25 miles northeast of Adak. Navigator Lt. Francis Xaver would say in his recollections about the landing: “As we flew over the 50 foot cliff on the shoreline, a strong wind blowing up the face of the cliff was so turbulent that it knocked out our radio, and we lost all contact with Adak. Unknown to us, Adak tried to contact us at about this time to inform us that a base was open somewhere up the chain of islands. Of course, we never received the message as our radio was out of order.” After waving off two attempts, Pruett lowered his speed to 130mph, extended his flaps, and kept the landing gear retracted. After the belly of the aircraft made contact, the plane slid 1000 feet on the mud and wet grass before coming to a stop, narrowly missing several boulders on the foothills of the Great Sitkin Volcano. While seven of the crew were survived without injuries, bombardier Holiel Ascol suffered a broken pelvis, and was carried out of the aircraft by the rest of the crew. After everyone got out of the Liberator, they stretched their parachutes over the left wing to create a temporary shelter from the drizzling rain while the radio operator sent out a message with a hand-cranked transmitter. Later that day, Pruett and his crew were rescued by USS Hulbert (DD-342) and returned to Adak to resume flight duties. The B-24, however, would have to wait half a century for its recovery.

Unlike the P-38, B-24s were maintained at Hill during the war, and were often serviced by female auxiliary personnel, who often filled the roles once occupied by men who were now overseas. Originally, another B-24D that rested on Atka Island, 40-2367, was considered for recovery, but having already been added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979, Alaskan Senator Ted Stevens was intent on leaving 40-2367 were it remained to serve as a permanent monument (indeed, it has since been incorporated into the Aleutian Islands World War II National Monument). With 40-2367 no longer an option, 41-23908 was selected for recovery instead. Like Arthur Kidder and the P-38, the Foundation tracked down Ernest Pruett, who had retired from the Air Force in 1960 as a Colonel and was living in retirement in Carlsbad, California, and invited him to accompany the recovery team, which he also accepted.

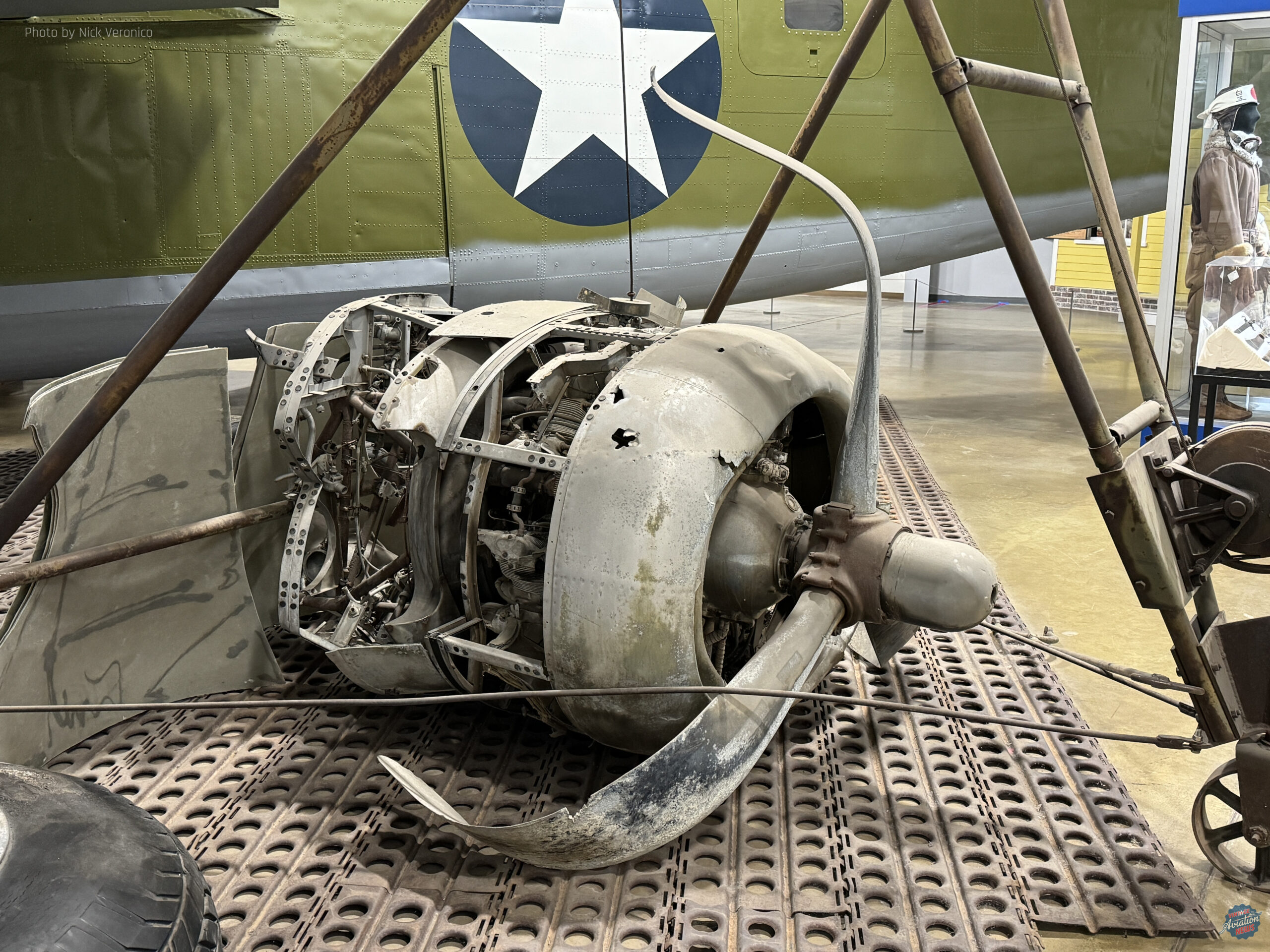

The task of retrieving the Liberator fell to a 20-man volunteer team of Air Force Reservists from the 419th Combat Logistics Support Squadron and the 67th Aerial Port Squadron, both based out of Hill AFB, led by team leader Master Sergeant Paul Cragun. Like the P-38, the men set out from a rented landing craft-type barge, the M/V Polar Bear, and used saws to cut the aircraft into manageable sections to be placed on cargo pallets and hauled back to the ship. Unlike the P-38, though, the Liberator parts had to be dragged down a 40 foot bluff, and since Polar Bear sprung a leak due to hitting an underwater rock, the barge had to be anchored 250 yards from the shore. Over the next ten days, the team dragged pallet by pallet from the crash site, until all that was left were the wings, which were flipped over so that the smoother topside was on the bottom, making it easier to drag the wings through the tundra grass with a cable from the Polar Bear. Later, the team used wooden beams to haul the part-laden pallets over the island’s rocky beach and used fishing buoys that had washed up on shore to float the parts to the M/V Polar Bear, which then set a course to Anchorage, where a pair of Lockheed C-5A Galaxies flew the Liberator parts to Hill for transport to Kal-Aero in Dulzura.

By 1996, Ed Kaletta had completed his work on the P-38J, which was trucked to the Hill Aerospace Museum, and began to focus his energies on the newly arrived Liberator. Though the forward fuselage and wings were able to be reused, there were not nearly enough parts from the tail to reconstruct an intact section of the aircraft. Kaletta had a solution for this in the form of the fuselage of Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer, Bureau Number 59932, which he had acquired from fellow restorer Tom Reilly. This Privateer had been previously converted into a weekend cabin in the Florida Everglades by Marvin and Barbara Droznenk, and Kaletta would use its tail section to replace the missing section on ‘908. Kaletta worked on grafting the hybrid Liberator/Privateer fuselage for the next seven years, and on May 17, 2002, the fuselage of the Liberator/Privateer hybrid, painted as it looked on its final mission, arrived at the Hill Aerospace Museum.

It wouldn’t be until November 2006, that the wings would join the fuselage in Utah. The following month the Liberator was finally reassembled with further interior restoration being conducted while inside the museum. Today, the Buldir P-38 and the Great Sitkin B-24 are displayed in close to proximity to each other in the Hill Aerospace Museum’s Hadley Gallery. Alongside the P-38 is an unrestored propeller and Allison V-1710 and with the B-24 is an unrestored Pratt & Whitney R-1830 engine and tail turret. In addition, the B-24 display features two mannequins portraying female mechanics at Hill Army Airfield servicing the number #3 engine, whose propeller is removed and lays adjacent on the wooden platform in front of the right wing.

It should be noted that the nose of Privateer 59932 was later purchased by Bruce Orriss and restored for the National WWII Museum in New Orleans, Louisiana, where it can be found today in the configuration of an armed photo-reconnaissance F-7 Liberator (42-64241) named Over Exposed. The nose section’s restoration was funded by James Sowell, whose father Billy flew the original Over Exposed in the South Pacific as part of the 5th Air Force.

Both the P-38 and the B-24 at Hill serve as silent reminders to the American airmen who participated in the Aleutian Campaign, whose hardships in the form of living conditions and flying weather were just as deadly as the Japanese forces they came to fight, and whose experiences are too often forgotten. But in a sense these two airplanes also provide an insight into the dedication of the people whose passion and drive brought them to cold, wet, uninhabited specks of volcanic rock and tundra grass to retrieve long-forgotten pieces of history, and through toil and through sweat, brought them out of the wilderness for a new lease on life, even if their engines will never roar again, to serve a greater purpose of keeping the stories of the Aleutians Campaign alive.

Special thanks to Nick Veronico for providing photos and information from his visits to the Hill Aerospace Museum for the production of this article.

My dad was one of the group who helped retrieve the P38 from the Aleutian Islands. We loved learning and hearing about this adventure, his stories, and being able to go watch the movie they showed for a time at the museum, the actual footage. Now it’s awesome to take the grandkids, let him show and tell about it. Awesome father and chance of a lifetime he was excited and honored to be a part of.

Thanks for sharing this!

Dulzura, CA.