by James Kightly

At the Vintage Wings and Wheels Museum in Poplar Grove, Illinois, a magnificent example of the Curtiss Jenny has become the museum’s centerpiece. Bearing registration N1DP on its rudder, this beautiful machine is far from being just another static, museum exhibit. While it looks authentic and well-loved, surprisingly this airframe is entirely brand new!

An iconic WWI-era trainer, with a firm place in aviation history, the Curtiss JN-4D ‘Jenny’ really should not need an introduction. With numerous surplus military examples in the USA after the Great War, the type became a mainstay of the 1920’s barnstorming era, with echoes of its presence lingering in aviation films ever since. So while the Jenny is at no risk of disappearing entirely from museums or even from the skies, unsurprisingly, it is no longer possible to find parts for the type in a local hardware store like one could back in the aircraft’s heyday. Jennys are no longer available as ‘war surplus’ or for a knock-down secondhand price either. So, other than paying a King’s ransom for an original airframe, how does one now go about acquiring an authentic-looking Curtiss Jenny to fly?

Well, you could just build a new one, as Chapter 1414 of the Experimental Aircraft Association and the Vintage Wings and Wheels Museum just did. The two organizations, both based in Poplar Grove, Illinois, collaborated to create a ‘new’ Jenny for the museum. With 1,200 relevant Curtiss Aeroplane Company drawings available, original data was not the problem. However, building a Jenny from the ground up is no easy task. Opting for a ‘new-build’ identity (rather than ‘rebuilding’ around a dataplate identity) the aircraft was authentic enough to receive a construction number (No.7685) in the same sequence as the last JN-4Ds off the original production line – an honor which the Shuttleworth Collection’s exactingly recreated Sopwith Triplane also received – signed off by none other than Tommy Sopwith himself, in that particular case.

Starting in 2017, and working mostly on volunteer days from 10 am until 3 pm on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Sundays, roughly two dozen people contributed to the aircraft’s construction over a five-year period. Led by Don Perry, with four primary builders, the effort involved around 22,000 hours of work. Interestingly, many of the volunteers were not actually ‘aircraft builders,’ in the words of team member Steve McGreevy, but under careful supervision, they were more than able to meet the task. The completed aircraft flew for the first time in late 2021 and took part in EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2022. With an average groundspeed of 52 mph (83 km/h), the Jenny performed in a fashion typical for its type and era, as its pilot, Ken Morris, found: “You’re flying it every second,” he said. After its appearance at Oshkosh, Ken added: “It’s now up to me and Jenny to get the 100 boat miles home (airplanes this old can’t tell knots). I didn’t go high and I was doing 52 mph ground speed. Then it happened. Slow and steady, I seemed to go back in time. Something near spiritual. Sunday morning at about 6:45, 2022 became Sunday morning 6:45, 1920s.

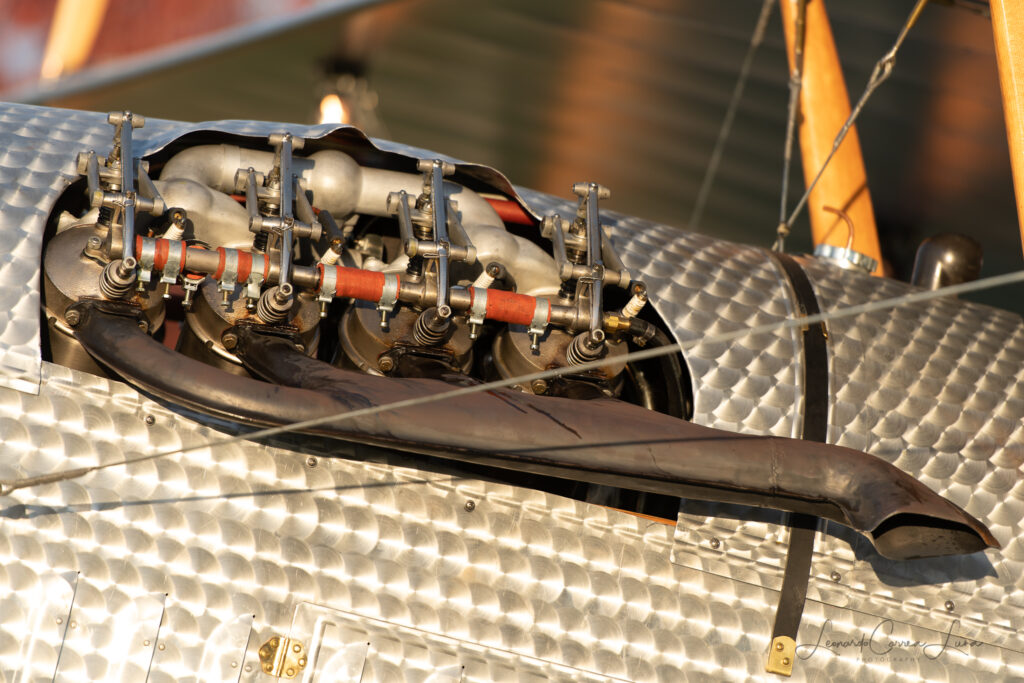

“There was nothing to give away the future. A cornfield is a cornfield. No big roads full of modern transportation. Looking down at green fields with the mornings’ golden glow, long shadows and farms. The open rocker arms mindlessly pivoting up and down, driven by an unseen camshaft, deep inside the 100-year-old engine. Lots of wild turkeys, deer and back roads. A farmer in his feedlot looked up, hearing the mighty OX-5 and waved. I waved back, noting the American flag on his grain bin. I swear it had 48 stars.”

Even with a ‘steerable’ tailskid, the aircraft requires a ground handling crew for normal operations, not least for hand-swinging the propeller (created from original drawings) to engage the engine, which has no starter motor.

The team created the Jenny’s distinctive, car-style radiator using a purchased set of square-section coolant tubes (shortcutting EAA member Don Perry’s proposed, far more laborious, hand-built core). The unit’s brass surround is all Perry’s work, however. Appropriately, the radiator cap is modified from that of a Ford Model T motor car. While authentic in almost every detail, the construction crew did elect to improve Jenny’s cooling by filling the radiator with a glycol mix, a technology that entered regular aviation use in the 1930s.

While the team had hoped to contract out the engine rebuild, they ended up doing it in-house, with Tim Gallagher leading this effort. They found a roughly 80% complete Curtiss OX-5 V-8 in Oklahoma to start with as a core. This engine, and a few instruments, are the only hundred-year-old period parts in the aircraft.

There is a lot of detail work in the aircraft. The metal engine cowlings have an eye-catching finish, recreating the original look with hundreds of carefully positioned swirls, known as ‘Jeweling’ or Engine Turning. Common to many aircraft types in the earlier Great War period, this kind of bare metal surface finish, while decorative, had a practical purpose as it helped disguise any marring which could occur during maintenance efforts. This was much appreciated by the hard-working barnstormers of the day, as the build team pointed out.

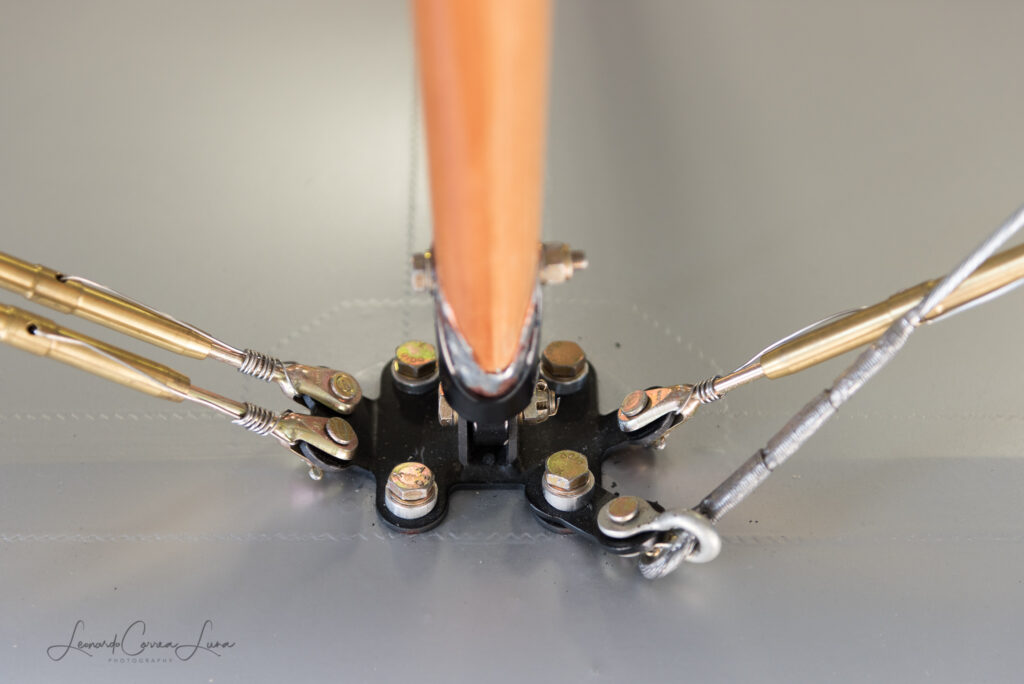

The build team were also able to modify modern, rectangular piano hinges for the cowlings, into the scalloped style which Curtiss originally employed. They also scratch-built a variety of control horns (integral hinge points) for the flying control surfaces, and when complete, surrounded them with a rhapsody of turnbuckles, cables, wires and swaged ends. The wire-spoked main wheels arrived as a gift. These units originated in Italy during the 1990s, part of a small production run for other Jenny restorations.

Bearing the fuselage logo for Poplar Grove Airport, the Jenny will become a focal point for the locally-based Vintage Wings and Wheels Museum, flying at local events to promote both the museum and the airport. The aircraft’s support team dress appropriately for the part during flight operations, wearing white overalls reminiscent of the 1920s which bear the famed ‘Curtiss’ logo across their back. This all contributes to an aura of period-authenticity around the aircraft, which is certainly eye-catching in the modern world!

As with almost every such enterprise, the Vintage Wings and Wheels Museum is a non-profit operation – thus the Jenny is too, and both need funding to keep going. It is important that the Jenny keeps flying too, as team member Ken Starzyk points out, “…to show the younger generations what aviation was like way back in the beginning.”

Now back at the airport after taking a star turn last year at Oshkosh, the Jenny is fulfilling its promotional task, entertaining and educating visitors, schoolchildren, and tech school students alike – a reinvention of the barnstormers’ role for the twenty-first century, with a twenty-first century made flying machine.

The Poplar Grove Vintage Wings & Wheels Museum, part of the 501c3 non-profit organization Poplar Grove Aviation Education Association, is dedicated to aviation and automobile history ranging from 1903-1957. Located on the Poplar Grove Airport (C77) in northern Illinois, the Museum is on 12 acres and has several early 20th century airplane hangars and automotive garages which have been saved from destruction and relocated to our campus where they have been renovated for future generations to enjoy. Our mission focuses not only preserving history, but also educating people. With that in mind, we offer a variety of outreach programs to area grade schools, field trips, summer camps, lectures, and a scholarship program. Check the various links on this website for more information.