2/264

According to legend, in the year 1307 the bailiff/agent of the Hapsburg Duke of Austria placed a Hapsburg hat on a pole in the town square of the small village of Altdorf, Switzerland. Once the hat was in position, he demanded anyone walking by to uncover their hats before it. As a local hunter/farmer and his son passed by, the older man refused to obey the decree.

Infuriated, the Hapsburg representative ordered the hunter, William Tell, to place an apple his son’s head, mark off 120 paces, then shoot the arrow off his son’s head. If William failed, he and his progeny would be executed. William marked off 120 paces, loaded and aimed his crossbow, and let loose the arrow. A perfect hit, the apple fell.

“Your life has been spared,” the bailiff stated. “But why did you place a second arrow in your jacket?”

William Tell replied, “If my first arrow had killed my son I would have shot the second at you, and I would not have missed.”

As folklore alleges, the apple was an easy target for William Tell because he never missed. Fortunately, William never targeted the Big Apple: New York City.

In the eyes of friends and foe alike, The Big Apple epitomizes the United States of America, more so than Washington, D.C. The city is a genuine melting pot, a multinational potpourri of race, creed, color, Libertarians and liberals, communists and conservatives. New York City is who and what we are. Thus the target rationale for 9/11. Its significance as a political bull’s eye has never been lost on our enemies.

Adolf Hitler was 8 years old in 1897, the same year the German military first seriously considered the continental United States as a target. Future wars and war planning would heighten that interest. In 1903 German Vice Admiral Wilhelm Bushsel merrily boasted, “A landing on and the occupation of Long Island with a resulting threat to New York from the western end of this island now seems feasible.”

During the late 1890s and early 1910s, the finishing touches on the “surprise attack” on New York called for: “Two sizeable naval units blocking access to the harbor, one at the eastern end of Long Island Sound and the second in New York’s lower bay. A battalion of engineers and several battalions of infantry would land on Long Island, assemble, and attack Manhattan the next day.”

During the Roaring ’20s an aspiring young German naval officer studied these plans for an invasion of New York. The ambitious officer was Karl Donitz, the future commander of Hitler’s U-boat fleet and, after Hitler’s suicide, the last fuhrer of the Third Reich. In 1901, German Kaiser Wilhelm advocated an invasion of Cuba so bases could be established for the future invasion of the United States.

The plans were shelved until World War II. A strike against New York, similar to the American air raid on Tokyo by Jimmy Doolittle, became an obsession with Hitler and the German military hierarchy. Damage was not the actual goal, but like Doolittle’s air raid on Japan, a psychological shot in the arm for the German people while spreading “terror” among the American population. Plus, the notion that such a raid on the United States mainland would force America to spend precious money, time, and resources to upgrade its coastal defenses was not lost on the Nazis.

A long-range attack across the Atlantic Ocean presented large, but not insurmountable, problems. Stratagems hit the drawing boards. Innovative aircraft called the America Bomber were designed and built. The Italians, desiring a piece of the action, jumped into the planning stage for the strike against New York. In truth, the Italians had the most reliable means and combat experience to actually pull off an attack.

First, the Germans. The America Bomber favored by most in the Nazi hierarchy was Willy Messerschmitt’s Me-264. Initially flown on Dec. 23, 1942, the four-engine bomber was approved for the long-range mission after necessary improvements were made on engine upgrades, armaments and midair refueling capability. The wingspan was slightly over 141 feet, about the same as an American B-29, and over 30 feet longer than a B-24. Fortunately for New Yorkers, on June 18, 1944 Allied bombers destroyed the prototype and two other partially completed Me-264s.

The Junkers Company built an enormous aircraft, the Ju-390. First test flown on Oct. 20, 1943, its wingspan was 40 feet wider than a B-29 and the fuselage 11 feet longer. The Ju-390 was powered by six 1,700 BMW engines and supposedly made a test run to the east coast of the United States. Two were built, both destroyed by Allied bombers or blown up by retreating Germans.

Ernst Heinkel’s company built the He-277. First flown in December of ’43, the company built at least eight He-277 America Bombers before production was halted in favor of fighter protection against Allied bombing. All eight bombers were lost to Allied air raids.

Focke-Wulf’s brainchild was the Ta-400. Focke-Wulf’s fighter aircraft, the Fw-109 and Fw-190, were legendary. The Ta-400 never flew, but had Germany spent the time and resources to take the Focke-Wulf design beyond the wind tunnel model, the American east coast would have fallen victim to its tremendous 22,000 pound payload. Powered by six big BMW radial engines, later altered with two Jumo 004 jet engines, this beautifully designed plane would have wreaked havoc on American cities.

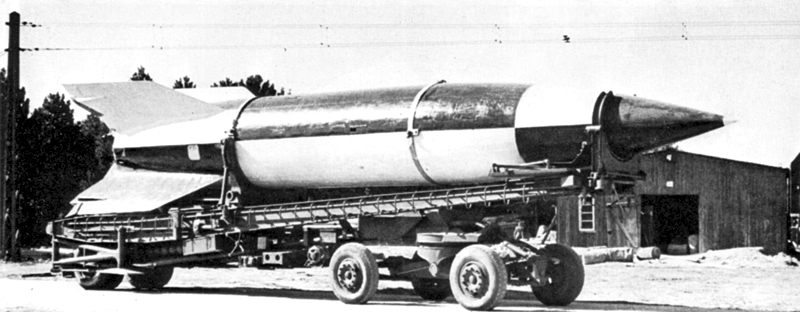

Had the war continued, no doubt Wernher von Braun and his scientists could have easily targeted New York with their highly successful rocket program. The slow V-1s and supersonic V-2s had rained destruction on London and other European cities near the end of WWII. Plans were in the works for the A-9 and A-10, rockets with extended range including two or three stage capabilities. After the war, von Braun admitted to American interrogators that studies had been conducted for construction of the A-11, basically a booster rocket attached to an A-9/A-10 combination that due to its orbital capabilities could hit any target on earth.

A scheme for German submarines to haul, actually tow, V-2 supersonic missiles enclosed inside a launcher for use against New York City came very close to reality. The predecessor for submarine launched ballistic missiles, one canister as they were called, was completed and two more near completion when the Soviets overran the project complex in Stettin in early 1945. The canisters and everything else at the complex were sent back to the Soviet Union.

German engineering was no doubt advanced enough to hit New York City or other east coast targets in the United States if for no other reason than a morale booster for the German people. Luckily for our East Coast, Hitler’s priorities bounced around like a rubber ball near the end of the war. Perhaps we should also be grateful Hitler was a candidate for a rubber-padded cell as well.

Now, the Italians. My grandparents came over on a boat from Sicily to start their new life as patriotic, hard-working American citizens. Albeit, a few folks of Italian lineage during WWII had plans to ride pigs into the Big Apple.

A “Pig” was a remarkably successful weapon used by the Italian Navy’s assault teams, the most famous being the Tenth Light Flotilla. The men of the Tenth were responsible for sinking or severely damaging 31 ships for an aggregate loss of 265,000 tons. These warriors used speedboats, miniature subs and manned torpedoes.

The Tenth called their manned torpedoes “Pigs.” Twenty two feet long and 21 inches in diameter, two men sat astride the weapon with their feet in stirrups to guide the torpedo to the preselected target, attach a 661-pound explosive device with timer, then hopefully slip away.

On Dec. 18, 1941, the Italian submarine Scire released three “Pigs” near the entrance to Alexandria harbor. Evading at least three British destroyers, the “Pigs” sank two British battleships, a fully loaded tanker, severely damaged a destroyer, and lived to tell the tale as POWs.

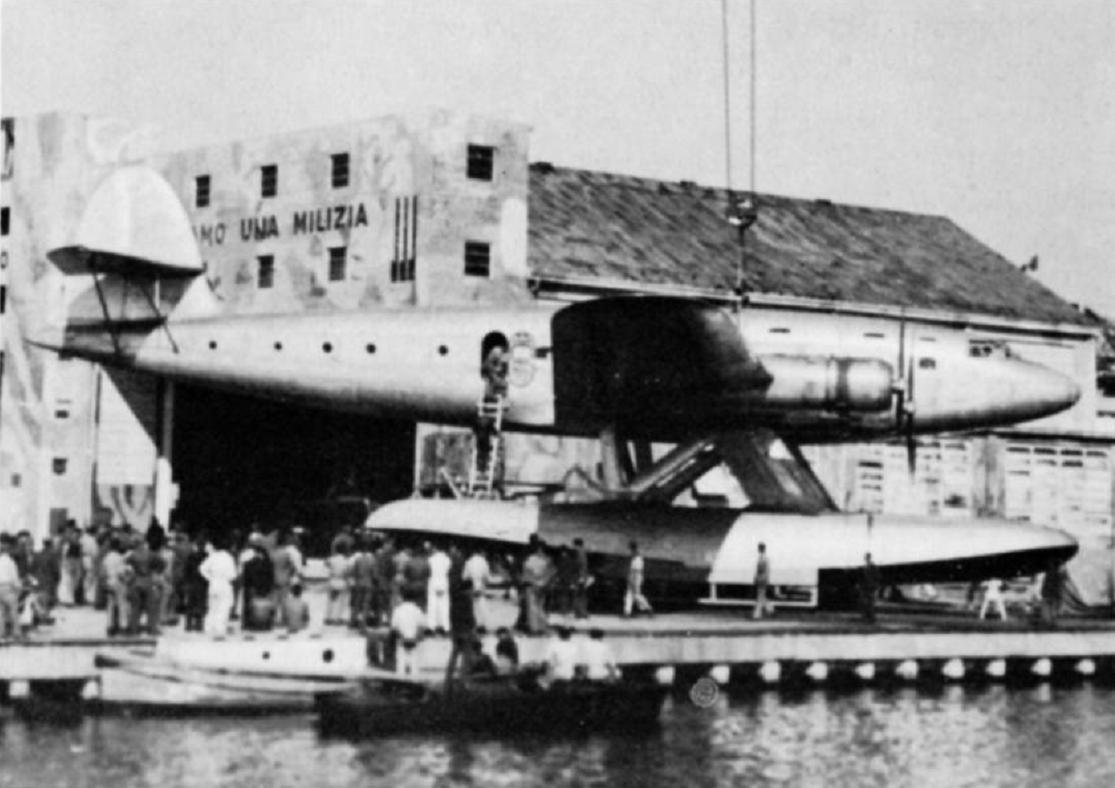

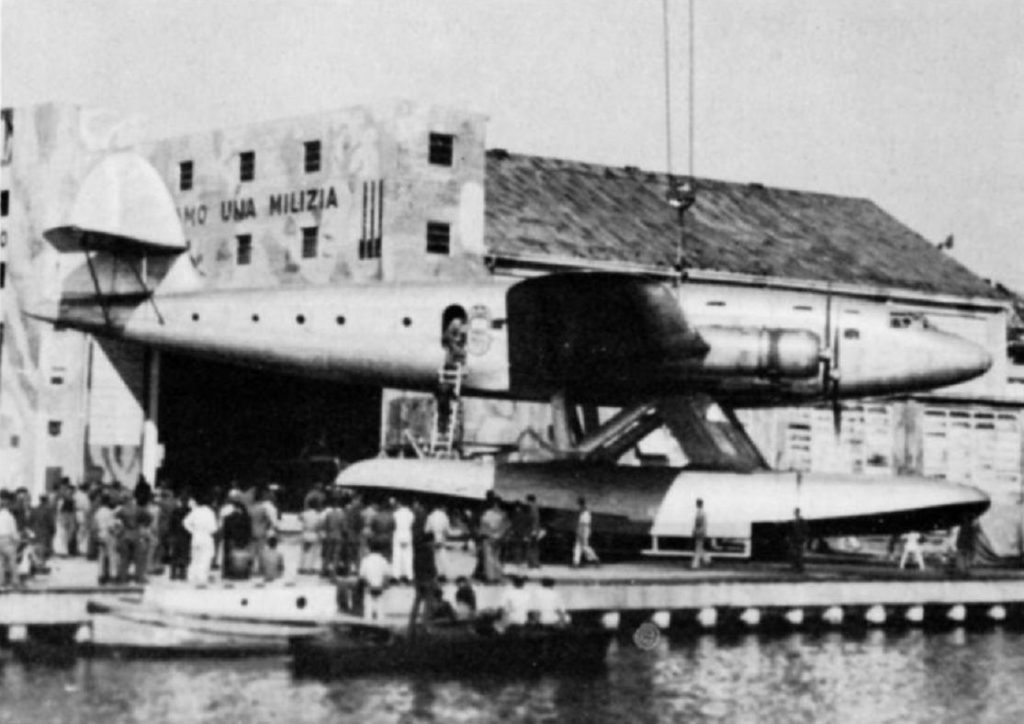

Bigger and better plans were drawn up, including an attack in New York Harbor. Carried to outside the harbor by four engine Cant Z.511 float planes, four “Pigs” would be released, the men would pick their targets in New York Harbor, then return to a designated pickup point. The plan did not have enough time to materialize.

However, a strike by Italian miniature subs was given approval. Limited in range, Italian submarine mother ships planned to transport the mini subs to within range of New York Harbor. The mini sub crews spent over a year in training for the New York mission. Once inside the harbor, each sub would release two torpedoes and a wide assortment of limpet mines.

The strike date was set for December of 1943. The attack was canceled in September, three months short of the attack date after the Italians signed an Armistice with Allied forces. The men of the Tenth were heartsick. These men believed in their mission, and most military historians agree the Tenth would most likely have succeeded.

After all the planning and feasibility for success, our enemies never hit the Big Apple. William Tell would have been disappointed.

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran. For story consideration visit his website at aveteransstory.us and click on “contact us.”

Related Articles

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.