By Pete Mecca

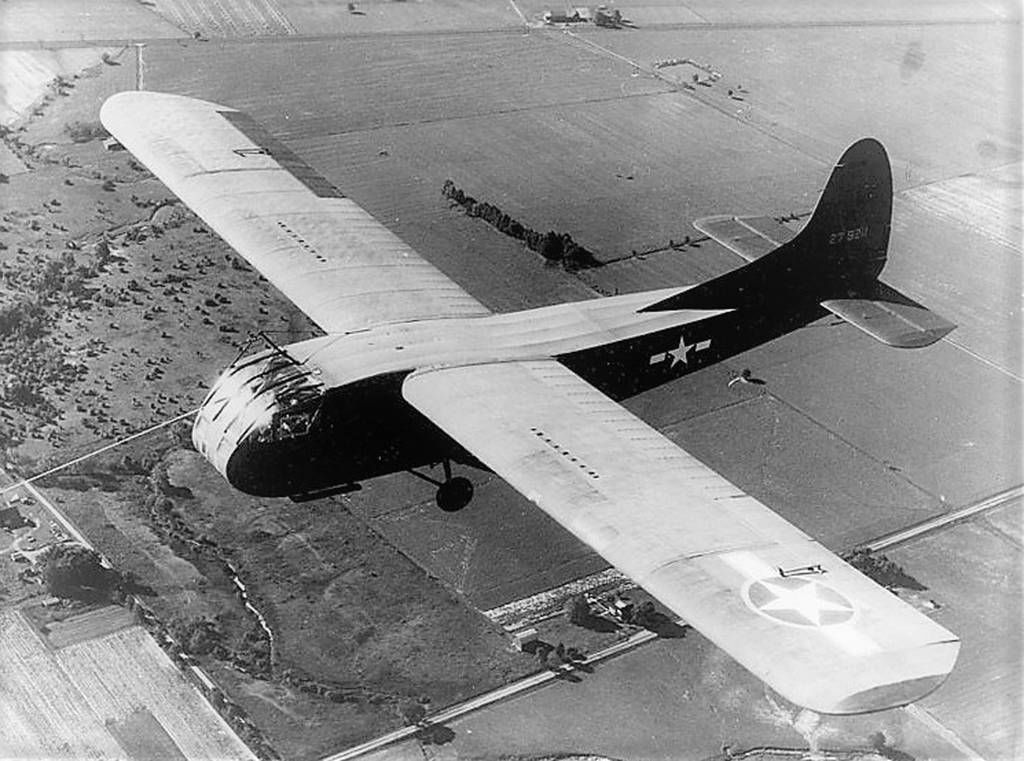

Like a deadly cobra, colorful anti-aircraft tracers swivel and coil around your aircraft; the flak is thick as molasses, and you and your passengers are going down. The normal descent is 72 mph, landing speed around 60 mph, but at 49 mph your aircraft will stall and crash, killing everyone aboard. Your flimsy flying machine was made by a variety of recognized American manufacturers, including beer conglomerates like Anheuser-Busch and the Schlitz Brewing Company, Gibson Refrigerator, the Ford Motor Company, Ward Furniture, a piano manufacturer, even a coffin company.

The air armada is 1,400 aircraft strong, you’re sitting on your parachute because the plywood pilot’s seat is too uncomfortable on long missions. Shrapnel rips through the fragile fabric overlaying a metal airframe and projectiles punch holes in the plywood floor. Motorized power is non-existent since the aircraft was constructed without an engine and you are slipping to earth while the soldiers aboard pray you paid attention during pilot training. The soldiers pray hard, for they understand that landing in a Waco CG-4A Glider can only result in two outcomes: very good or very dead.

During late 1941 and early into World War II, the Army utilized sailplanes for glider training. That decision was a huge mistake since sailplanes take advantage of thermal conditions and can soar for hours with a skilled pilot behind the controls. Not so with Army glider pilots. Their abilities required aerial truck drivers with the proficiency to land the equivalent of a trailer with a pair of wings in combat conditions. A casualty rate of 78 percent was not unusual. Most glider pilots flew only one or two missions; Guy Gunter flew four major combat missions in a Waco Glider. And this is his story.

An Atlanta native, Gunter was born on June 6, 1918. He attended Murphy High School and Tech High, and recalled the day Pearl Harbor became a household word. “I was employed by General Electric at the time as a traveling salesman. I was having lunch in an Atlanta restaurant when I heard the news about Pearl Harbor. You know, every individual in that restaurant knew a war had started, but I didn’t think too much about it. I think I was too young to really understand the significance.”

Gunter desired aviation. By late 1942 he had been interviewed by a Navy Flight Board in Macon and accepted for pilot training. “That’s what I wanted to do,” he said. “But in the meantime I received my ‘greetings’ from Uncle Sam. At the time a draftee could go into the Army and still receive a transfer to the Navy when a slot opened up in pilot training. I was sent by the Army to Shepard Field in Wichita, Texas, to take instrument training, then became an instructor and waited for a call from the Navy. And I waited, and I waited. That call never came because the transfer program had been terminated.”

Gunter applied for, then was accepted for OTS (officer training school). “I made friends with one of the instructors,” he said. “I told him I wanted to fly. He called me two days later and offered glider school. I took the deal.” Thus began Gunter’s lifelong love for aviation.

Sent to Hayes, Kan., Gunter learned to fly from fields cut out by tractors and bulldozers. “I got my wings in Piper Cubs,” he said. “I soloed after four hours of training. I loved it. I kept doing ‘touch and gos,’ you know, practice landings and takeoffs. Well, the instructors finally had to wave me down. I didn’t want to stop.”

Lubbock, Texas, and advanced glider training: “Actually, what they called a glider was an airplane with the engine removed,” he said. “We trained with Aeroncas and Taylorcrafts. Without engines there was room for three seats, trainee in front, instructor by his side, and a second trainee in the back. When the Waco gliders finally arrived they were pulled in by L-2s with fighter jocks piloting the gliders. It was funny to watch the fighter pilots. They were scared to death wrestling with dead stick aircraft.”

The first class of glider pilots graduated on Nov. 14, 1942. “There were 109 of us in the class,” Gunter recalled. “The Army said we would be assigned as instructors in Austin, Texas. Yeah, right. We found ourselves on the former luxury liner SS Maripose headed for Egypt by way of Rio de Janeiro, an unescorted 45-day voyage.”

Egypt was a barren land, and barren of gliders, too. “I flew copilot on C-47s or C-46s for about 30 days,” Gunter said. “We also relocated to Algiers and Libya on occasion to fly cargo flights into Gibraltar, Oran and North Africa. Of course, we flew missions back to Egypt on whiskey runs.”

Gliders arrived almost overnight. Gunter recalled, “I flew into Algiers one day and saw gliders all over the place. Our training began immediately, very intense training. We had a lot of fun but knew something was up.” That “something” was the invasion of Sicily.

Gunter said, “We trained the British pilots for three weeks, then they asked for American volunteers. Well, being as foolish as I am, I volunteered. We had 35 glider pilots on the first flight; only 16 of us made it back. It was a real slipshod affair. An old Army sergeant piloted our tow plane. The thick anti-aircraft fire got on his last nerve so he wanted to cut us loose. I knew we were too far out from the port of Syracuse and told him so; I said we couldn’t make dry land. Obviously, he didn’t care. Here comes the rope; we’d been cut loose. We flew into a hornet’s nest. Shrapnel peppered my face and legs, plus the glider took a lot of damage but the flight characteristics were OK. I put it down in the bay. We remained in the water all night clinging to the glider. A captain in our group told me to say a prayer for everybody. Shoot, I told him to pray for himself, I was too busy praying for yours truly!” Luckily, the next day a Greek destroyer picked up the men instead of German Naval vessels.

Transferred to Sicily, Gunter flew cargo planes until assigned as a pilot on a four-seat single engine Fairchild 24. “I flew the big brass around the island for about six months,” he said. “As you may have noticed, there’s plenty of spare time between missions for glider pilots. Shoot, I had a ball.” It didn’t last long. Gunter received another transfer, this time to England to prepare for the Invasion of Normandy: D-Day. Asked his opinion of the English people, he replied, “Well, at least the girls understood what the heck we were saying.”

June 6, 1944, the Allies invade Europe: “We took off just after midnight carrying a pathfinder group of the 82nd Airborne. An hour later we put down about 25 miles south of the main front. We had no problems, we made it down, we were very lucky. I brought the glider in nose high, hit on the tail and plowed straight into a hedgerow. That was OK though, it stopped the glider. We’d taken Dramamine pills and a shot of scotch, so we were up to the task. I remained on the ground for about six days.” Asked what glider pilots do after landing, Guy replied, “Try to stay alive. Most of us had a carbine or Tommy gun so we joined the fight.”

Gunter’s next port-of-call: a miniscule village near Mount Vesuvius in Italy. “There wasn’t much to it,” he said. “The base was scraped dirt runways and not much more.” Operation Dragoon was on the horizon; the men and gliders made ready for the invasion of Southern France. Gunter said, “The fields in southern France weren’t a problem; the problem was all the tall poles the Germans put up to prevent glider landings. Shoot, we didn’t care, we landed between the poles. The poles tore the wings off but we kept the fuselages on course so we did OK. The paratroopers had a rough go of it. As they oscillated in their chutes many would slam into the poles, a lot of those boys broke their backs.”

Gunter continued. “We fought against the Germans and Vichy French for about 48 hours. I didn’t have a lot of love for the Vichy French, none of us did. Anyway, after things calmed down I ‘confiscated’ a 1936 Model V8 Ford with a big charcoal burning tank on back. We had a ball in that car until we had to quit.” When asked to explain “quit,” he replied, “The dang fire burned out.”

Back to England, to participate in the largest airborne assault in military history: Operation Market Garden, the botched attempt by British Field Marshall Montgomery to enter Germany via the Netherlands. Airborne resources flew 34,600 troops into combat: 20,011 by parachute, 14,589 in 3,140 various gliders. A shortage of American and Allied glider pilots meant using one pilot per glider with an additional soldier occupying a copilot’s seat. The glider air armada was pulled to their landing assault areas by 1,438 C-47 or C-46 cargo or transport aircraft. The mentioned statistics do not include ground force participation in Operation Market Garden.

Gunter recalled, “The gliders in our formation flew directly over a German anti-aircraft school. A bit scary when you think about it, but we came in too low for them to hit anything. We had a real smooth landing and we all got out safely, if 45 miles behind enemy lines can be considered safe. I grabbed my weapon and joined the combat, just trying to stay alive, as always. We assaulted the bridge at Nijmegen.”

Pausing a moment, Gunter continued, “When a glider is cut loose from the tow plane the pilot wants to get down as soon as possible because they are always shooting at you.” When asked to explain the meaning of “as soon as possible,” Gunter responded, “As fast as humanly possible!” One glider flight characteristic seemed unnerving, especially to yours truly, an amateurish pilot who fancies an engine attached to his aircraft. Gunter recalled, “We never looped a glider on a combat mission, but I did loop several gliders in training. However, I couldn’t roll one.” When asked why not, Gunter replied, “Let’s put it this way, I never tried.”

Against all odds, Guy Gunter survived his fourth major combat assault as a glider pilot. He returned to England and flew as copilot on cargo planes until assigned to Reims, France to pilot C-46 Commandos. Volunteering for the last glider mission of the war into the heartland of Germany, the Army denied Gunter’s request. “They said four glider landings in a combat situation was enough,” he said. “I guess the Army was right. Two of my best friends at the time flew into Germany; it was their initial mission as glider pilots. Neither one made it back.”

After the war Guy Gunter eventually went into his own business as an appliance distributor and stayed in the air with his personal aircraft, a Beech Bonanza and twin-engine Beech Baron. He still remembers one particular flight to Florida. “The Bonanza swallowed a valve and blew a hole in the block. I cut air to the engine, which put the fire out, but oil was all over the windshield and I had no power, so I put ’er down, took six trees with me and landed nose up. I had chipped bones in my ankles and the guy with me broke his pelvis, but nobody really got hurt. Lost a good plane, though.”

He also landed the twin-engine Baron without an operable nose wheel. “No big deal,” Gunter said. “I kept the nose up until low speed and gravity forced the nose and twin props into the runway.” Gunter’s hours behind the controls of military and civilian aircraft, including over 1,800 hours in gliders, approached 30,000 when he finally retired his wings at a ripe young age of 92.

Asked if he missed the wild blue yonder, Gunter replied, “I still have 20/20 vision, my faculties, and this dang walker. Tell you what, take me to an airport and stand me next to the wing. I’ll crawl up into the cockpit, I’ll pull myself into the pilot’s seat, and I will get that baby airborne. You bet’cha.”

I interviewed Guy Gunter several years ago. As cocky as all aviators are known to be, the talk we shared was one of the most pleasurable of my writing career. Guy Gunter passed from this life on Nov. 2, 2016, at the age of 98. No debate is required concerning his position beyond the Pearly Gates; Gunter earned his wings a long time ago.

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran. For story consideration visit his website at aveteransstory.us and click on “contact us.”