By Luigino Caliaro

Sunday April 29th, 1945 marked the first weekend following the effective cessation of hostilities in Italy during WWII. At the military barracks in Milan, only recently occupied by the Garibaldi Rocco and Redi partisan brigades, the officers of 1° Gruppo Caccia of the RSI (Repubblica Sociale Italiana) were gathered, following the signing of their surrender by the unit’s commander, Maggiore Adriano Visconti. This document signed with the partisans allowed the officers an honorable surrender, while the NCOs and troops were set free, with guarantees of personal safety for all parties. Visconti had arrived at the decision to sign the surrender document with considerable reservations. Nevertheless, his desire to spare more useless bloodletting prevailed over the pride of a soldier, and after praising the efforts of his men following more than a year of combat operations in almost impossible conditions, he placed his signature on the document. He remained convinced that despite this surrender, 1° Gruppo of the RSI had conducted itself with honor until the final days of the war, performing its duty as a defender of the Italian people. In the early afternoon, some partisans summoned Maggiore Visconti from his quarters, on the pretext of an investigation, and he duly reported with his aide, Sottotenente Valerio Stefanini. As the two men crossed the courtyard, a few bursts of machine gun fire rattled out, echoing loudly across the building, an ill omen of what was later publically confirmed by the partisans themselves. Totally against the agreement previously signed by all parties, Maggiore Visconti, the charismatic Comandante of the 1° Gruppo Caccia RSI, and Sottotenente Stefanini, had been assassinated by some of the partisans, who fired a deadly burst of machine gun fire into their backs as the two officers walked to their appointment. In this tragic way, the life of one of the most respected Italian fighter pilots was brought to a sad end, a much loved commander who led one of the famous fighter groups that fought tirelessly and with limited equipment against the overwhelming power of the Allied air forces which ranged across the skies of Northern Italy during the final year of World War Two.

Adriano Visconti was born in Libya on November 11th, 1915, and following high school, he enrolled in the REX course at the Accademia Aeronautica, the fabled Air Force Academy for the Regia Aeronautica (Royal Italian Air Force) in Caserta, Italy. Becoming a military pilot in 1939, he was soon posted to the 159a Squadriglia (Squadron) of the 50°Stormo (Wing), based at the time in North Africa and equipped with the disappointing Breda Ba.65 attack aircraft. Visconti didn’t stay long with the unit as, following disciplinary action, the commander transferred him to a liaison unit flying the Caproni Ca.309 Ghibli twin engined transport/reconnaissance aircraft. He distinguished himself in combat flying one of these ungainly-looking beasts by successfully surviving an attack by three RAF Gloster Gladiators, earning himself a Medaglia di Bronzo al Valore (Bronze Medal of Valor). Posted back to 159°Squadriglia, Visconti completed his operational tour, remaining with the unit until its disbandment in January, 1941. Visconti then joined 76a Squadriglia, a fighter unit assigned to 7° Gruppo (Fighter Group) of 54°Stormo, and commenced his career as a fighter pilot flying in the Macchi MC.200 Saetta. Despite intense flying activity, Visconti’s first victory didn’t come until June 15th, 1942, by which point his squadron had upgraded to the far more potent Macchi MC.202 Folgore. This combat occurred during the Battle of Pantelleria at the end of an air engagement when he managed to shoot down a British Bristol Blenheim. A few weeks later, on August 13th, Visconti added two RAF Spitfires to his account.

Visconti had to wait for a few more months before officially becoming an ace. Returning with his unit from North Africa in April 1943, he managed to down two enemy aircraft over Bourigne: a Spitfire on April 8th and an American P-40 Warhawk on April 29th. Soon after, Visconti became Comandante (Commander) of the newly constituted 310a Squadriglia Caccia Fotografica (Photo Reconnaissance Squadron). Just prior to leaving his old unit he managed to shoot down a Spitfire Mk.V on May 6th over Cape Bon, although there is some evidence that this is unconfirmed. Visconti’s posting to a photo-reconnaissance unit was certainly linked to the experience that he had previously acquired, as on many occasions he had flown surveillance missions in MC.200 and MC.202 fighters modified to house cameras. Towards the end of August, 1943, Visconti managed to operationally deploy an initial section of Macchi MC.205V, a long range, drop tank equipped version of the Veltro. He flew on the first operational sortie on August 28th; a reconnaissance mission lasting almost two hours.

The Armistice of September 8th, 1943 came like a bolt from a clear sky and Visconti, completely isolated and without orders, returned to Rome to try and gain a better understanding of the events that were unfolding, and also to avoid any possible reprisal from German forces still present at their base in Decimomannu, Sardinia. Eventually, still without any instructions on how his unit should behave, and without any transport aircraft to evacuate his personnel, Visconti decided to fly the unit’s fighters to mainland Italy. The journey brought the majority of the pilots home, sharing cockpits as a last resort. They arrived at Guidonia, near Rome, with a flight of three single seat Macchi MC.205Vs disembarking some 11 pilots!

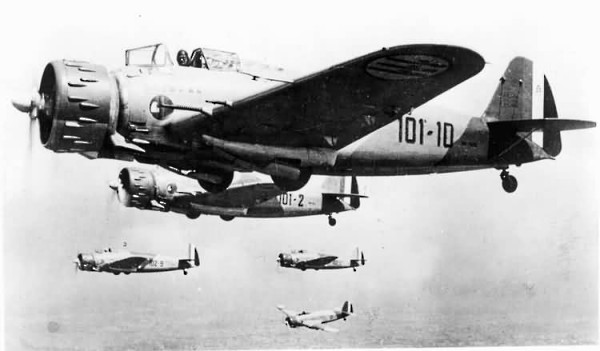

In those moments of absolute confusion, Visconti took the decision to adhere to the RSI (the Repubblica Sociale Italiana), maintaining faith in his original military oath of allegiance, and was assigned to the 1° Gruppo Caccia, equipped with the Macchi MC.205. This choice is clear evidence of Visconti’s character and patriotic spirit. He was not particularly pro-German, and this is confirmed by the fact that it was Visconti himself who requested the overpainting of German crosses on the RSI’s fighters with the Italian national insignia, albeit slightly different to those used in the early years of the war. Visconti soon took command of 1a Squadriglia, and began to fly the Veltro on desperate missions to counter American bombing raids, engaging in furious combat with their P-38 and P-47 escorts. On January 3rd, 1944, a P-38 Lightning would become his first victim while serving with the RSI, and in the course of the following months he obtained a further three confirmed victories before receiving command of 1° Gruppo Caccia posted to Germany for conversion onto the Messerschmitt BF-109G-6, the aircraft in which he would fly during the final months of the war, prior to its tragic epilogue.

Maggiore Visconti, over the course of five years of war, was decorated with four Medaglie d’Argento (Silver Medals) and two Bronzo (Bronze Medals) for valor, and the German Iron Cross class I and II. In total, he was credited with ten confirmed victories and 26 probables.

CONFIRMED AIR COMBAT VICTORIES

AIRCRAFT FLOWN LOCATION DATE AIRCRAFT DESTROYED

1) Mc 202 Pantelleria 15-6-42 Bristol Blenheim

2) Mc 202 Mediterranean 13-8-42 Spitfire V

3) Mc 202 Mediterranean 13-8-42 Spitfire V

4) Mc 202 Bourgine 8-4-43 Spitfire V

5) Mc 202 Cape Bon 29-4-43 P-40 Warhawk

6) Mc 202 Cape Bon 6-5-43 Spitfire V

7) Mc 205V South of Cuneo 3-1-44 P-38 lightning

8) Mc 205V Po Estuary 11-3-44 P-47 Thunderbolt

9) Mc 205V La Spezia 25-4-44 P-38 Lightning

10) Mc 205V Emilia 30-4-44 P-38 Lightning

WarbirdsNews would like to thank Luigino Caliaro and Giorgio Apostolo for the help in the composition of this article.

Squadra Atlantica and Aviation Graphic have collaborated to produce a unique scarf and an exclusive lithograph of Maggiore Visconti’s airplane. Click on the image to purchase it.

Related Articles

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.

You have forgot to say that the men who gave the order to shoot Maj. Visconti and Lt. Stefanini. will be in italian parlament and Major of the city of Milano !

Con rammarico il 25 Aprile non ho sentito nessuno ricordare questi valorosi piloti che combattevano per difendere l’Italia dai bombardamenti alleati. Tutti onorano I fratelli Cervi

ma nessuno si ricorda dei fratelli Covoni. Spero che un giorno ci sia

una revisione storica che possa considerare il 25 Aprile tutti vincitori o tutti perdenti.

Interesting that you have so much information on Visconti, a pilot fighting in support of the Nazis, but no information on Clark Eddy, an American ace who bested Visconti in a dogfight and shot him down. Clark Eddy lives in my neighborhood in Sacramento, CA and is highly respected around here. Here is the link to the quote from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adriano_Visconti

Visconti was not fighting in support of the Nazi, Visconti was flying to protect the Northerner cities of Italy. It is well proven that Visconti was an anti-fascist. We would love to know more and interview Mr. Eddy if you could help us to do so. Regards, Moreno.

His country capitulated, but he fought not for libefators, but Nazis. Killers of Allies is no hero.

Visconti was a Hero. He did not fly for the Nazi, he flew with a small group of other pilots to protect the populations of Northern Italy. He wasn’t pro Mussolini and nevertheless pro Hitler. In my opinion a pilot who decides to fly and fight against 50-60 allies airplanes by himself, to protect his own people, is a HERO.

Me. McGrew, se can’t change history and the very situations that made these aviators choose the course of action. Visconti and his men were soldiers and felt the urge to defend the civilian populations against the carpet bombings that were striking the Italian cities. This is part of a soldier’s duties, beyond any political ideal… Please note that Adriano Visconti’s picture is portrayed in the Smithsonian Institute, as a tribute to the ace, even if fighting on the opposite side. That’s the highest sign of appreciation to the man, the aviator, the leader, beyond the side he was standing for. In my humble opinion this is the correct way to approach history, and learn the good and the bad lessons from it. After 70+ years we can try to understand, but in order to make any judgement we should have been in their shoes at that time and in that desperate environment.

Well said Roberto.

If you would like to Charles Clark Eddy Jr., the U.S. pilot who bested Visconti, to contact you, I will pass along your phone number if you send it to my email, and he can call you. By the way, Clark tells me he is not an ace, although I think if a pilot downs an ace he should be considered an ace. James McGrew

James, we would love to talk with Charles!

While doing some research on Visconti the ANR, etc I found this link. There is a brand new art print issued of Eddy and his head on attack with Visconti

It is called “Deadly Pass” by Anthony Saunders and you can see it at http://www.brooksart.com

If Clark is still with us you should get him to sign a copy!

I would be very interested to hear how he is doing since I am a volunteer at the Museum of Flight in Seattle and put on presentations

Take care,

Alex Boras

[email protected]

503.608.0696

Colgo l’occasione di questo bel ricordo di Adriano Visconti, per un commosso saluto a Franco Benetti, ex Pilota Anr, scomparso l’anno scorso.

Custode instancabile del Ricordo di Adriano Visconti e degli altri valorosi piloti che hanno combattuto per la difesa delle città italiane, selvaggiamente colpite dalle incursioni alleate.

Franco Benetti ha curato, con amore infinito e fino alla fine della Sua esistenza, la Sala d’Onore dell’Aviazione Nazionale Repubblicana, ospitata al Castello di San Pelagio.

Gheregheghez! carissimo, indimenticabile Franco.

The dogfights involving the pilots of Fighter Groups of ANR in the skies of Northern Italy were real mortal combat.

The chances of survival of these brave, were extremely low, if you consider the simple fact that for every Italian pilot, flying there were a dozen allies.

It ‘amazing how, despite this absolute disadvantage, the Italian hunters managed to bring splendid victories