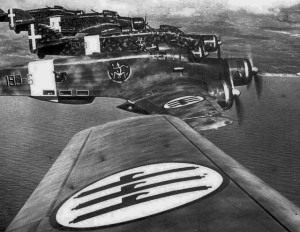

at the controls of his Savoia-Marchetti SM.79

1st Lieutenant Dalmazio (Dal) Corradini (February 2, 1919- March 10, 2009) flew for the Italian Air Force’s Aerosilurante (Torpedo Bomber Arm), which was among the most successful units of the Second World War, crippling shipping to and from the British base at Malta as well as coming close to tipping the balance of the war in North Africa. The unit was responsible for destroying more Allied war and merchant ships than Italy’s entire surface navy and it was the unit’s bravery and willingness to take on difficult and extraordinarily dangerous missions, often flying unescorted daylight sorties, that arguably makes their bravery and skill the equal of any of the Allied forces’ more celebrated aerial combatants. That the Axis powers lost the war has certainly muted the celebration of the bravery of these patriots who were acting in what they believed was the best interests of their homeland.

Dal was still a child growing up in Naples when Italo Balbo, the Minister of the Air Force, flew a squadron of twelve Savoia-Marchetti S.55 flying boats from Orbetello, Italy to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil followed a couple of years later by a flight of twenty-four flying boats on a round-trip flight from Rome to the Century of Progress Exhibition in Chicago, Illinois. His bold aerial feats earned him a hero’s status worldwide, but particularly in Italy, he was viewed as a symbol of national pride. The impact of his airborne flotillas were such that “Balbo” entered the common Italian lexicon to describe any large formation of aircraft. It was in this environment that the young Dal grew up dreaming of becoming an aviator.

In 1938 at the age of 19, Dal joined the Italian Air Force as a trainee for officer’s school and became a second lieutenant pilot in June 1940. While in training in Pescara he and his compatriots flew mono-engine biplanes such as the Breda Ba.25, Fiat CR.20, Breda Ba.25/D.2 and Fiat CR.32. Later at the Aviano Air Base, Corradini was certified for multi engine planes such as Savoia-Marchetti SM.81, SM.79, SM.84, SM.79 II, Caproni Ca.100 and the SM.81 bomber. Over the course of the intensive training regimen, pilots were sorted by their abilities, and Dal’s skills at navigation and steady handling of the stick got him assigned to the Bombardment Unit, 228th Squadron, which in combination with the 229th, formed Gruppo 89.

Lieutenant Corradini’s first mission was on May 10, 1941, a bombing run in his SM.79. Over the course of that year he would complete five bombing missions. In 1942 they received new equipment in the form of the SM.84 which they piloted for the year and 12 missions. In December of 1942 they were re-assigned the older SM.79 which was much more maneuverable than its newer counterpart, a change which Dal and his crew heartily approved of, though as fate would have it, they only flew three missions in 1943.

As far as missions, Dalmazio flew a total of 20, five as a pilot-bombardier and 15 as a torpedo pilot, all against the British Fleet in the Mediterranean from his base on southwest coast of Sardinia at Milis. While the war took its toll on the Italians’ supply lines, often forcing him to the controls of an aircraft literally held together with tape and bailing wire, with the exception of the one case, when he was forced to return home with his torpedo un-deployed, due to fierce British aerial defenses that prevented him from getting in range of his target, Dal always found a ship to hit. At the end of every mission the aircraft crews would have a meeting with their commander, and if it was a collective action, with the crews of the other aircraft that participated in the sortie. In those meetings they would all discuss the results of the mission, for instance they would confer on what the various members of the crew(s) observed and images their cameras had captured on film. While they were often able to confirm hits on enemy ships, in most cases it was impossible for them to say with certainty whether the ship was sinking or not. For obvious reasons, few pilots were inclined to hang around the attack site to take pictures, as the level of armament the Allies could muster, given enough time, would make it a one-way mission for certain.

The fateful mission that would take Dal out of the hostilities occurred on March 27, 1943. When Dal arrived at the airfield, the engines of his plane had already been started and were going through the normal warm-up period. The members of his crew of five which consisted of the second pilot, a sergeant and the radio man, engineer and machine gunner were all waiting for him, as was his Captain who told him what his mission would entail. His plane, with possibly a second craft following in reserve were to go to the Gulf of Philipeville on the Tunisian coast to torpedo a cargo boat coming in from Gibraltar which they would attack around noon. They were to travel with other aircraft from the squadron, including Gruppo 105, but as it turned out their plane suffered damage to the right landing strut during the taxi-out to the strip. Dal and his crew had to scramble to take another aircraft that was airworthy and in the meantime the rest of the squadron had formed up and left. Over the course of the flight they unsuccessfully tried to catch up with their group, but ended up arriving to the action late, attacking the Allied cargo ship alone.

When Dal and his crew arrived, the targeted ship appeared to be stationary, and Dal managed to get it lined up in just a few seconds. The two corvettes escorting the ship heard their engines but started shooting too late, the torpedo had already been released and soon exploded. As Dal recalled it, “The ship split in two sections forming a “V” with front and rear in the air and the middle section slowly sinking.” The broken, sinking ship was a spectacular sight and Dal asked the engineer who doubled as the photographer to take all of their 35 exposures of the sinking vessel. In retrospect, it was the wrong thing to do. As Dal circled around the ship, losing precious minutes from his limited escape time, not only were the two corvettes firing upon them but British Spitfire Mark V’s with twice their speed and packing devastating firepower were already on their way. Once one of those ferocious warbirds latched onto his tail, the one small Breda machine gun that a crewman might be able to get a clear shot rearwards was little defense, particularly in an airplane that mostly consisted of wood and fabric.

Dal and his crew were trying to fly home, not much more than 10 feet above the surface of the water when they were set upon by two Spitfires. The first round of bullets shot ahead of their plane, which Dal took to be pilot-to-pilot “sign language” meaning: “I am giving you a chance to bail out before I shoot you down.” They were flying too low to attempt a parachute jump and so they had no choice but to keep on flying, but it would turn out to be a very short run. Before they could even get stationed at their comparatively puny machine guns, their left engine was struck by the Spitfire’s 20MM cannons and the wing’s integral fuel tank started burning.

Missing an engine and with a fuel tank afire, Dal managed to ditch the plane before it exploded. They hit the water and were submerged for a while, but after what Dal described as an seeming like an eternity, the plane bobbed up to the surface. Dal and his men, badly burned from the fire, scrambled out on to the wing and retrieved the self-inflating life-raft. Rowing away from their stricken and now slowly sinking plane, the men watched as the Spitfires circled, making them men wonder if they would be fired upon in their extremely vulnerable state. Instead, after making several rounds of the crash site the planes waggled their wing tips and headed off. Later a small spotter plane appeared overhead and circled before shooting up a red flare, marking their location for the rescue ship that would soon appear.

One of the corvettes that had been shooting at Dal during the attack came to rescue their attacker. As they pulled up someone shouted at them in English, which they did not understand and then in German “are you German or Italian?” One of the crew was from Northern Italy with a rudimentary understanding of German and managed to answer that they were Italian. Severely burned, with hands so badly charred that the flesh was curling off, Dal was led to the bridge where he was presented to the officer in charge who asked him something in English, and when he got no answer he asked in French (as it turned out the ship that rescued them was Canadian), “Who is the officer?” Dal, who understood French raised his arm and the bridge officer came close and snapped to attention, saluting with his right hand touching the visor of his cap he said, “Monsieur, bienvenu sur mon bateau!” When Dal’s men asked for the meaning of what was said, Dal answered, practically in tears, “We have been shooting at each other until some minutes ago and now this man tells me, “Welcome on my ship, Sir.” We all had tears in our eyes, including the Canadian sailors. I was taken to a small room and placed on a cot while a crewman helped remove my flight jacket.”

The ship landed in port and Dal and his crew were carried off-ship on stretchers, borne on the shoulders of the ship’s crew, put in an ambulance and taken to a nearby British tent hospital. It was there for the first time that Lieutenant Corradini first came face to face with the realities of war. In an interview years later, Dal stated: “Before this, war was just another form of sport for me, like boxing. I beat you or you beat me- or like a bullfight, I kill the bull or can even get killed by the bull. I saw people burned like charcoal; they were the sailors of the ship we had torpedoed and they were suffering much more than we did. This is when I saw what our torpedoes did to the victims; and (I) felt ashamed to have caused such damage.”

While they were at the field hospital, an English medical officer who spoke French told Dal that they did not know what to do with them as they really didn’t even have enough room for even their own wounded. There was also some concern that they might have to hand them over to the local Free French garrison, who, given the German and Italian treatment of Free French prisoners, stripped of their rights under the Geneva Conventions due to the Axis classifying them as pirates, would very possibly execute Dal and his crew at their first opportunity. Fortunately the next day an American DC-3 landed in a nearby field to bring supplies to the hospital and someone must have told the pilot about the Italian aviators and their predicament, because he elected to take them with him to his base in Casablanca.

Later when they had landed in Casablanca, Dal had occasion to talk to the pilot through a Moroccan who spoke both English and French. The pilot was from Texas, he said, and Dal thanked him for his kindness while also expressing his hope that the pilot would not have any trouble due to bringing them to the American base without orders from his superiors. According to Dal, the pilot’s answer was: “We all belong to an international fraternity of flyers; you fly, I fly, we are brothers; I wanted to help you and I did it. If my bosses don’t like it, they can fire me!”

As Dal related in an interview: “The American tent hospital in Casablanca was enormous and practically empty. During the first week in the hospital, every other day I as taken to the infirmary on a cot, given a shot in the arm to be put to sleep and have my bandages changed. My hands and head were completely covered in bandages with a few openings for my eyes, nostrils and mouth. After medication I would be taken back to my bed in the tent where I would wake up some time later. One day, as I woke from my medication, I found an American sergeant sitting on my cot. As I opened my eyes, he asked me, in very good Italian, “How are you doing?” “Do you feel better now?” I thought this would be a questioning session where they would try to find out about my plane, its armament, the location of my base, etc. I answered in Italian and said, “I already gave my name rank and serial number; therefore don’t bother me, go away and let me die in peace!” The American didn’t go away; he reached for his cigarettes, put one in my mouth and lit it. Then he said, “I’m not here to question you about the war; I only want to know if you are from Naples”. “Yes” I said, “I am from Naples, what is it to you?” The Sergeant asked, “Do you have relatives in the States?” “Yes” I said, “An uncle, my fathers brother and an aunt, my mothers sister.” “Where are they” asked the sergeant. I said, “I do not know”. He asked, “What is your uncles name?” “Francesco,” I answered. He then asked, “Do you know him?” “No” I said. Now the American wanted to know if my uncle Francesco had a family and I said, “Two boys”. “How do you know that? “Well,” I said, “we had a picture around the house of these two kids, with bow ties, all dressed up like for a first communion.” The sergeant then asked, “Do you know their names?” I said, “No.””

At this point, the sergeant became more and more agitated, started moving his hands and stuttered, “I will tell you their names, one is Dominic and one is Joe, and …..and I am Joe!”

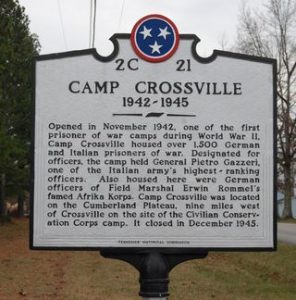

Dal landed in New York and was initially placed in a Naval Hospital to treat his burns. Then all the medical case POWs were placed on trains and sent, initially to the POW camp in Crossville, Tennessee (where Dal’s Uncle Frank made the trip down from Kenosha to pay him a visit), and later, before the 1943 September surrender of Italy, Dal was transferred to Monticello, Arkansas.

In October 1945, Dal was sent back to Italy and resumed a life of studies and exams until December 1946 when he was awarded a Ph.D in Political Science. In 1947, Dal accepted an invitation to move to the states extended by an uncle on his mother’s side of the family, and Dal moved to Detroit, Michigan. After an initial period of part-time jobs and study at Wayne State University to learn the language, Dal was awarded a B.S. in Business Administration.

On September 3,1949 Dal married Amelia Busch, his lifelong wife and mother of their 4 children, and a week later, Dal started teaching at the University of Detroit. As it turned out, the US Department of Education decided to honor his Italian Ph.D as his doctoral thesis happened to have been on the United States Constitution. Dal went on to fully epitomize the American Dream, leaving teaching after a few years to go on to a very successful career working for some of the most powerful corporate entities of the day before striking out on his own and founding his own company which he was able to leave his oldest son in charge of when he retired.

(Image Credit: Ken Arnold)

Dal passed away in Florida at the age of 90 in 2009, leaving behind his wife of 60 years, and a life very well lived.

Article re-written and published with the permission of Ken Arnold.

I Piloti non muoiono mai solo svaniscono e non li vediamo piú.!!!!

Il mio piú sincero rispetto a tutti quelli che, pur sotto bandiere differenti, combatterono dimostrando il loro valore difendendo quello che consideravano giusto. Il coraggio e’ da riconoscere e da rispettare sotto qualunque bandiera!!!

Great article about my father. He was a wonderful person and shared some great stories with us children. He is missed by so many because after he retired, he volunteered helping hundreds of business persons with marketing and import/export knowledge and advice which was very much appreciated.

Questo articolo è stato scritto molto bene! Grazie per le belle parole, fotografie e le memorie del mio carissimo papà! Lucy Corradini Aguirre

Lucy, would you mind to get in touch with us? [email protected] – Grazie!

What an inspiring story! I would have loved to meet this extraordinary gentleman.

Uncle Dal’s wartime adventuress, as well as his later adventures as an American citizen, have always been so intriguing to me. He was a fascinating and inspiring man.

He used to frequent a shop I worked at in Florida. I enjoyed chatting with him when he came in. He made a great Limoncello!!