There were almost a dozen shrink-wrapped pallets of boxes sitting on the rain soaked ramp at Ted Stevens International Airport (ANC) in Anchorage, Alaska. The address labels indicated that all of the packages were bound for the general store in Stebbins, Alaska. Everything from toilet paper and paper towels to dog food and candy were on these pallets. Perched on the edge of the Bering Sea, Stebbins is a Yup’ik Indigenous village that, like so many in Alaska, are only accessible by boat and aircraft. On the evening of June 26, 2024, a fire started in a shop next to the Tukurngailnguq School and quickly spread to adjacent buildings, and these supplies were restocking the depleted shelves of the general store.

The weather on that day, September 12, 2024, was rather miserable, but not atypical for Alaska with fall a few days away—45 degrees F, ceiling less than 500 feet, and a cold, steady rain. The handful of employees on the ramp, however, were loading radial-powered C-47A, USAAF #42-108983 (N272R) and DC-3C-TP, c/n 14994 (N560PT), a beautiful all-white turbine Dakota as if it was a warm, sunny day in Florida. No day at DesertAir is typical, though.

DesertAir was founded in Utah in the 1990s, delivering auto parts across the country and Canada. DesertAir then flew fish seasonally in Alaska with the reliable workhorse of the Alaskan interior, the Douglas DC-3. In 2001, the company began year-round charter air freight cargo service to rural villages across Alaska. Every year they added direct points of service to remote Alaska destinations. According to their website, DesertAir now serves over 200 locations from home base at ANC and any of its 24 hubs. From Wales on the Bering Strait and Deadhorse on the edge of the Arctic Ocean to Dutch Harbor out in the Aleutians and Yakutat in the south, if you can dream it up and DesertAir can get it in the door, they’ll deliver it direct and non-stop, 24/7.

The author’s visit to DesertAir was part of an aviation photography adventure arranged by Rich Cooper and Steven Comber of the Centre of Aviation Photography (COAP) and our guide was aircraft mechanic Michael Fritcher, who offered further insight on DesertAir’s “We fly any cargo, anytime” moniker. “We haul everything. From construction materials and oil drilling equipment to groceries and furniture. We have explosives permits, so we can carry explosives. We’ve delivered flat-bottomed boats to hunting lodges. We take a lot of road construction equipment to some of the villages along the northwest coast that are military bases. Things like light poles, and building equipment, building supplies.”

“Right now, its moose hunting season, so we’ve been hauling the hunters’ equipment, like four-wheelers and pallets of food and alcohol, to and from the hunting areas. We only fly cargo, no passengers, so they take a charter and then they’ll meet us there. They’ll help us unload. They’ll help us load again when they’re ready to leave. We bring the charter back here and we offload their equipment. We pretty much take anything that will fit in the door.” Michael laughingly added that when they go out to pick up the hunters and their kills, they are expected to drink all the alcohol because they displace the weight of the alcohol with moose meat. “That’s their job, to finish it,” he said.

The DesertAir DC-3s are truly some hard-working freight dogs. With cargo doors measuring 84 ½” wide, 70 ½ to 55 ½ tall and a max cubic capacity of 1,230 cubic feet, they can haul up to 6,500lbs of cargo and still get in and out of runways as short as 2,800 feet. And, they are not limited to paved runways as their large tundra tires allow them to operate off of the gravel and dirt strips that dominate the remote areas of Alaska. When asked why these 80+ year old aircraft have not been replaced by a more modern aircraft, Michael said, “The DC-3 has a unique position, especially up here in Alaska, as far as hauling freight out to the villages and into the bush. There’s really nothing that they’ve built since the DC-3 that will carry the load and be able to get into the short, unimproved airstrips that we go into. The shortest we could probably manage would be about 1,900 feet. I know takeoff, I’ve been told, about 2,300 feet. Most of the airports that we go into are between 3,000 and 3,500 feet and a lot of them are just literally carved out of the woods.” Perhaps it’s true that the only replacement for the DC-3 is another DC-3.

There is virtually nothing the DesertAir Dakotas won’t haul. Their website clearly states, “If it fits, it flies.” In addition to serving tribal communities and flying hunters out into the bush, DesertAir customers include Alaska state & local governments, Department of Interior, Division of Forestry, mining industry, oil and gas companies, mining industry, among others. All of the staging and ground handling of cargo is handled within a TSA-controlled area at Anchorage for maximum security. This allows DesertAir to accept and safely store cargo until it is ready to be loaded.

The quartet of Gooney Birds operated by DesertAir are an eclectic group with widely varied histories. The newest addition is the previously mentioned N560PT, which began life as C-47B, USAAF #43-49178. After a few days with the USAAF, the aircraft was allocated to the Royal Air Force (RAF) but was not taken up. Instead, it was delivered directly to the South African Air Force (SAAF) in October 1944 and served for eleven years before entering the civilian market. Over the next 23 years, the aircraft carried several different registrations while flying with six different owners. In July 1978, it re-entered SAAF service and received it’s turbine and fuselage conversion. The aircraft arrived in Anchorage in July 2024.

One of the hardest working Gooney Birds is C-47A USAAF #42-108983 (N272R), which was delivered to the USAAF on September 21, 1944. Shortly after the end of the war, this veteran was pressed into airline service with Transcontinental and Western Air-TWA as NC88824. Between January 1952 and July 1965, Eight Two Four flew with Beldex Corporation and Atlantic Aviation Service. On September 10, 1965, three months after going to work with Louisville-based Central American Airways Flying Services, the now registered N272R, was involved in a mid-air with a Cessna 150 at 1,800 feet. The Cessna crashed, killing the 41 year-old student pilot and the crew of Seven Two Romeo shutdown the #1 engine and returned to Louisville.

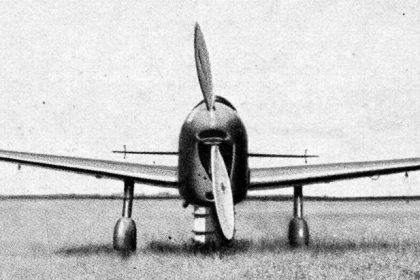

Over the next four-and-a-half decades, N272R passed through four owners, including Westinghouse Electric Corporation where it served as an avionics testbed and was fitted with its distinctive long nose, which it still retains to this day. When it was acquired by DesertAir in May 2010 it was in bare metal and remains so today with the exception of the “DesertAir” titles across the top of the fuselage.

Currently in its 24th year with DesertAir, C-47A USAAF #42-92995 (N44587) served briefly with the US Transport Command in North Africa and returned to the United States in August 1945. The following year the aircraft went into service with West Coast Airlines and later Pacific Western Airlines until 1966. In January 1969, the aircraft was acquired by Aerodyne Corporation of Renton, Washington, but when the company went out of business in 1974, Five Eight Seven was abandoned in Renton and became derelict. It was saved in 1988, when it was purchased by Salair Air Cargo of Seattle and after passing through two other operators, the aircraft went into service with DesertAir.

As we watched Six Zero Papa Tango and Seven Two Romeo taxi out and disappear into the scud over the airport the author asked Michael how long DesertAir will be able to operate these venerable classic DC-3s. He said that they have the parts to fly them for at least another quarter century, by which time the design will be 115 years old and their current fleet of aircraft will be pushing 110! One couldn’t help but wonder how surprised Donald Douglas would be to see his revolutionary design still flying a century after its first flight. Then again, maybe he wouldn’t be so surprised.