With “The Other First Man,” we launch a series of articles called Flight Test Files dedicated to the captivating stories of aeronautical advancements pioneered first by NACA and later by NASA over the years.

The “Flight Test Files” series of articles explores the aircraft used by the Dryden Flight Research Center over the years in its pursuit of aeronautical advancements. Since the 1940s, the Dryden Flight Research Center in Edwards, CA, has built a unique and specialized capability for conducting flight research programs. This organization, composed of pilots, scientists, engineers, technicians, mechanics, and administrative professionals, has been and continues to be a leader in the field of advanced aeronautics. Located on the northwest edge of Rogers Dry Lake, the complex was originally centered around the administrative hangar building constructed in 1954. Over time, additional support and operational facilities have been added, including unique test facilities like the Thermalstructures Research Facility, Flow Visualization Facility, and Integrated Test Facility. One of the most notable structures is the space shuttle program’s Mate-Demate Device and hangar, located in Area A to the north of the main complex. The lakebed surface also features a Compass Rose, providing pilots with an instant compass heading. The Dryden complex originated at Edwards Air Force Base to support the X-1 supersonic flight program. As other high-speed aircraft entered research programs, the facility became permanent, expanding from a staff of five engineers in 1947 to nearly 1,100 full-time government and contractor employees by 2006.

by Stephen Chapis

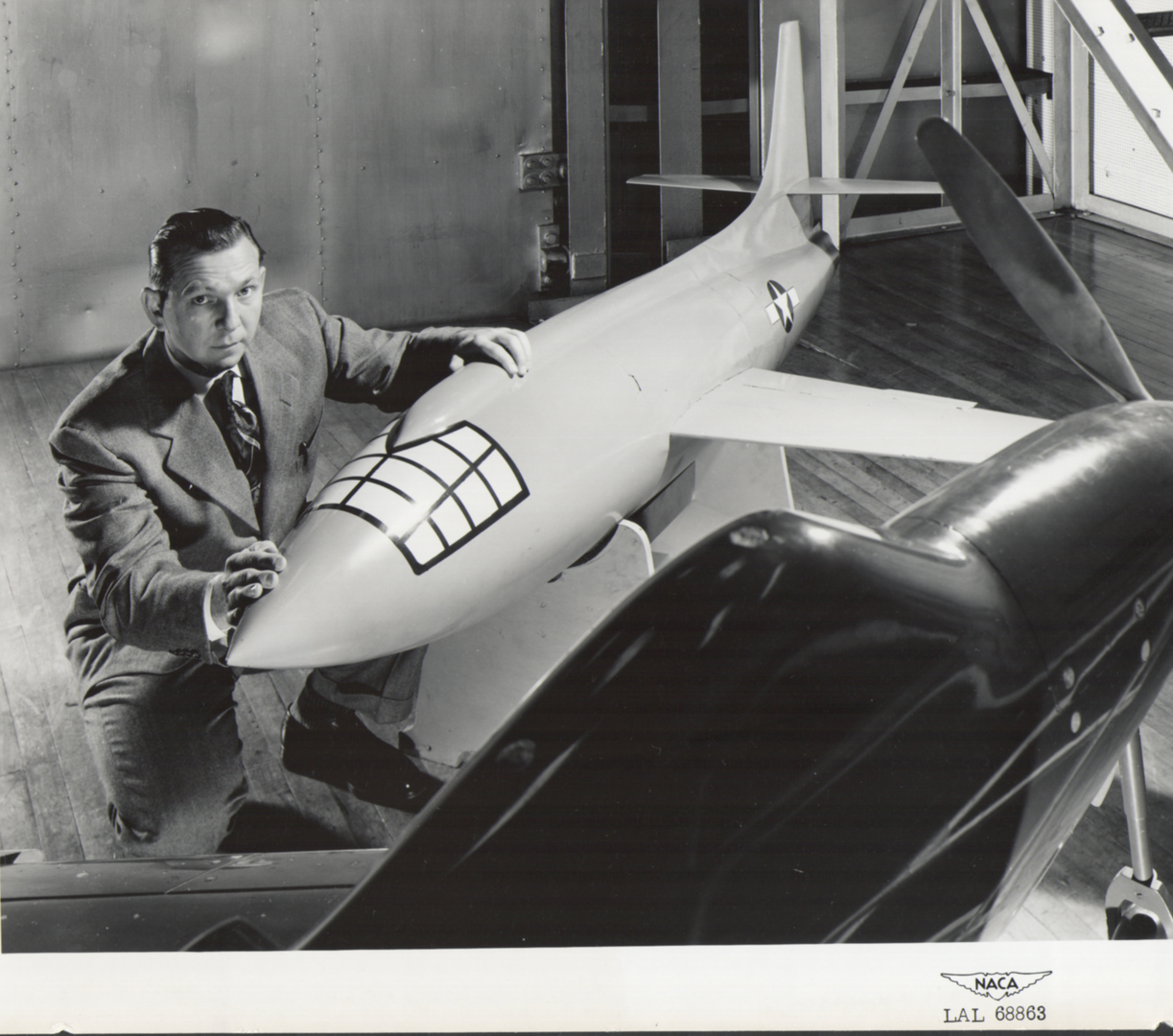

The first generation series of experimental X-1 rocket-propelled aircraft is arguably the most famous set of X-Planes to ever shatter the silence in the skies over California’s Mojave desert; the Bell Aircraft Company constructed three of these bullet-shaped research aircraft. While eighteen test pilots flew a combined 151 flights in these aircraft between January 25th, 1946 and July 31st, 1951, the only flight which people seem to remember today is Captain Charles “Chuck” Yeager’s sortie on October 17, 1947, when he became the world’s first human to fly faster than the speed of sound. Amongst all that has been forgotten about the X-1 program is another “first” flight which took place on March 10th, 1948, when NACA test pilot Herbert H. Hoover became the first civilian to break the sound barrier, flying X-1 Ship #2 (46-063).

Upon graduation with a degree in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Tennessee in 1934, and even though his mother said he seemed to have little interest in flying, Hoover joined the U.S. Army Air Corps, receiving his flight training at Randolph and Kelly Fields in Texas. In 1937, while assigned to Mitchell Field on Long Island, New York, Hoover took the U.S. Civil Service exam, hoping for a position with the Department of Agriculture. When that option failed to materialize, he accepted a job with American Airlines. However, before Hoover could start his airline career, a general pulled some strings to secure him a job flying for the Standard Oil Company in South America.

After three years with Standard Oil, Hoover returned to the United States to become an experimental test pilot with the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) in Hampton, Virginia, where he soon rose to chief of flight operations. During WWII, Hoover flew hundreds of research flights in a wide variety of aircraft, some of which nearly ended in catastrophe. Once, while flying a Curtiss Helldiver, the dive bomber’s canopy smashed into Hoover’s face when it suddenly departed the aircraft; despite his injuries, he was successfully able to safely land the ‘Beast’ back at Langley. On another occasion, when he was tasked with firing a rocket-propelled model from his P-51 Mustang during a Mach 0.7 dive, the model disintegrated. Debris from the model punctured his Mustang’s radiator, but again Hoover executed a successful emergency landing.

When the Air Force-NACA transonic flight research program began at the Muroc Flight Test Unit in California, Hoover and Howard Lily initiated NACA’s flight operations on October 21, 1947 when he performed the first NACA flight in Bell X-1 Ship 2 (46-063). Two months later, Hoover performed NACA’s first powered flight, obtaining a speed of Mach 0.71, with a second flight reaching Mach 0.84 on the same day. He flew another checkout flight to Mach 0.84 on the following next day. In January 1948, Hoover and Lilly completed seven subsonic flights, reaching a maximum velocity of Mach 0.925.

The flight on March 10th, 1948 was designed to investigate stability and loading. When Hoover’s X-1 was released from the B-29 mothership, he lit three of the four rocket chambers and quickly climbed to 42,000 feet where he leveled off and accelerated to Mach 0.93. When he lit the fourth and final chamber, the X-1 shot through the ‘sonic wall’ and ultimately reached Mach 1.065, approximately 703 mph. It had been a flawless flight that day, however as Hoover set up for his landing on Muroc’s dry lakebed, he discovered that the rocket-plane’s nose gear would not extend. With the aircraft essentially a glider at this point, its rocket fuel expended, Hoover had no option but to land. Once he touched the main wheels down to the lake bed, he held the nose off as long as he could to slow the aircraft down as much as possible before the nose inevitably settled into the dirt. The rocket plane skidded to a stop, thankfully with minimal damage. The inauspicious end to the flight did nothing to diminish its historic nature of course; Herbert H. Hoover had just become only the second person and the first civilian to break the sound barrier!

Following the announcement of Hoover’s supersonic flight, Hoover’s mother told the Knoxville News Sentinel, “He won’t tell us much. A lot of his work is secret, but his wife and children spent the winter with him at Norsco, California, where some of the tests were made.” She went on to say when he visited them in March 1948, “We got mighty little out of him.”

Later that year, at a ceremony in Los Angeles, Jack K. Northrop awarded Hoover the Octave Chanute Award for 1948 for “…contributions to the application of flight test procedures to basic research in aerodynamics, and the development of methods for scientific study of transonic flight.” In January 1950, President Truman presented Hoover with the Air Medal for “…meritorious achievement while participating in aerial flight… in piloting an experimental aircraft faster than the speed of sound, thereby providing valuable scientific data for research in the supersonic field.”

Unfortunately, like so many test pilots of that era, Hoover paid the ultimate price while practicing his craft. On August 14th, 1952, he and J.A. Harper were in a North American B-45 Tornado when the jet aircraft suffered a sudden and catastrophic wing failure near Burrowsville, Virginia. Both men ejected from the stricken bomber, with Harper receiving only bruising to a shoulder in his escape, but Hoover was not so fortunate. Rescue crews found his body a few hours after the crash; his parachute unopened. The crash investigators never isolated the accident’s cause, nor why Hoover’s parachute failed to open, but they suspected his body struck the airframe upon his exit. Whatever the cause, it was a sad end to a remarkable flying career studded with bravery… hopefully more people will now remember Herbert H. Hoover for his service to aeronautics and to the nation.

Related Articles

Stephen “Chappie” Chapis's passion for aviation began in 1975 at Easton-Newnam Airport. Growing up building models and reading aviation magazines, he attended Oshkosh '82 and took his first aerobatic ride in 1987. His photography career began in 1990, leading to nearly 140 articles for Warbird Digest and other aviation magazines. His book, "ALLIED JET KILLERS OF WORLD WAR 2," was published in 2017.

Stephen has been an EMT for 23 years and served 21 years in the DC Air National Guard. He credits his success to his wife, Germaine.