For those of us old enough to have used film cameras, it is becoming hard to recall the complexities involved. Even the most basic digital camera today can capture an almost unlimited number of perfectly exposed, sharply focused images with ease in almost any lighting situation – no matter the competence of the operator. We can share these images with the world almost instantaneously as well. However, back in the 1950s, most cameras had only manual settings for focus, exposure – and even film winding – all with rolls of film containing just a handful of frames and a sensitivity typically no higher than ASA 64 (ISO 64 in today’s parlance). Zoom lenses were almost unheard of, for the most part, and even telephoto lenses were a rarity too. So capturing even competent images with a camera in those days demanded technical excellence from the photographer. And this exercise was far, far harder when trying to photograph a moving object such as an aircraft. Sharing your images with fellow aviation enthusiasts involved an entirely different process too…

So it is worth looking back at those times to understand what it took for aviation photographers to excel and grow as a community. We are really pleased, therefore, to present the following article from A.Kevin Grantham, who describes how his close friend and mentor, David Ostrowski, a founding member of the American Aviation Historical Society, made his way as a budding aviation photographer in St.Louis, Missouri during the 1950s using a typical camera of the day, the redoubtable Kodak Six-16…

Richard Mallory Allnutt (Chief Editor – VAN)

MASTERS OF THE KODAK SIX-16 – DAVID OSTROWSKI

by A. Kevin Grantham

David Ostrowski is a man of many talents. He is an accomplished pilot, engineer, magazine editor, aviation historian, and avid collector of vintage desktop models. He is also an outstanding photographer, and in the early 1950s, he began his journey to becoming one of the MASTERS OF THE KODAK SIX-16 camera.

Growing up in St Louis, Missouri, Ostrowski was like many boys with a passion for aviation at the time; he built model airplanes and collected every aviation-related book and magazine article he could find. On Saturdays, when his Boy Scout troop visited nearby neighborhoods collecting paper to recycle, the young Ostrowski claimed dibs on any airplane magazine, especially World War II-era issues of Popular Science and Popular Mechanics. It was around this time when Ostrowski first met Bob Burgess, who had a similar passion for aviation; the two became lifelong friends.

“Bob and I met at a High School Science Fair where I had a display with a large scratch-built Convair XFY-1 ‘Pogo’ model I made,” said Ostrowski. “We were both delighted to meet someone else with a strong interest in airplanes. Before that, we thought we were the only guys on earth who were nuts about airplanes!” They teamed up with other boys in the area to form a group called simply The Airplane Club. “We would alternate meetings at each other’s house on Saturdays,” recalled Ostrowski, “…[and] occasionally would entice one of the parents to take us out to Lambert Field to look at airplanes.” In the meantime, club members began writing to aircraft manufacturers for information and photos of their products.

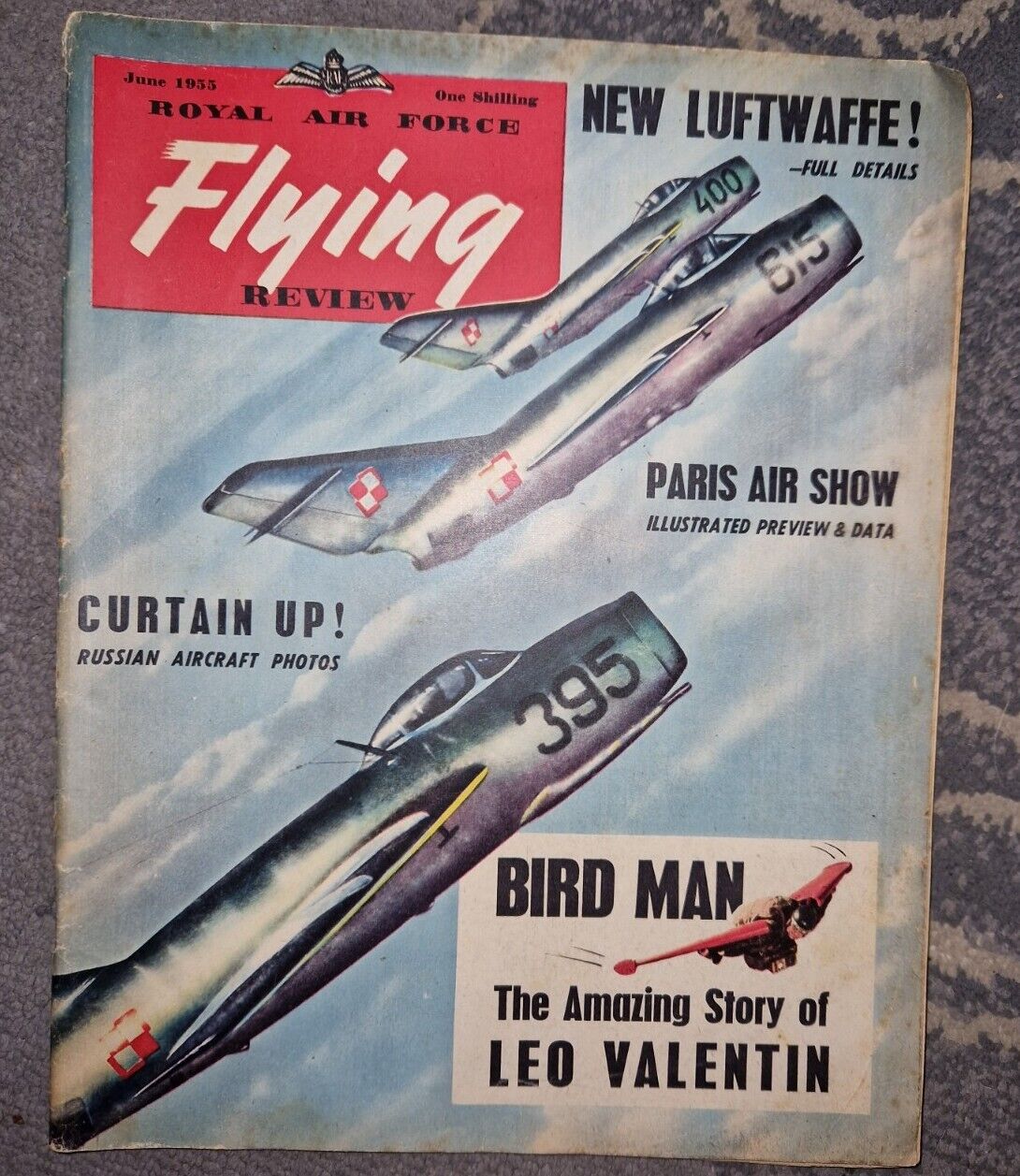

They also discovered a British aviation magazine titled Royal Air Force Flying Review (RAFFR) which, unlike its American counterparts, regularly featured articles highlighting aviation history. RAFFR also carried subscriber requests for pen pal partners worldwide. Looking back at that time from where we are today, with such instant access to virtually any person in the world, it’s hard to imagine the level of effort one once needed to connect with people sharing a similar interest. But that was how things used to be. Through their correspondence and club outings, Ostrowski and his friends developed a keen interest in photography.

Most of them used family cameras to begin with, as Ostrowski relates… “The first airplane photos I took were of the P-51s stationed at Scott Air Force Base. That was in 1953. I was thirteen years old. My dad drove onto the base, and we walked the flight line without anyone bothering us… a sharp contrast to the permissions needed today to access an active fighter base! Of course, the quality of my first negatives could have been better. I later learned that the more established photographers used higher-quality Kodak Six-16-style cameras. My mother took me to antique and camera stores in the St Louis area. We found a decent Six-16, which I later sold to my friend Bob Burgess after purchasing a Kodak Monitor… the same type of camera my pen pal William ‘Bill’ Larkins was using.”

For those who know little about the history of film photography, Kodak introduced its Six-16 film and camera format in 1932. The first Six in the name represented the number of exposures per roll of film. This was later increased to eight shots per roll, but the Six-16 moniker name was not changed for marketing purposes. This new 2.5 by 4.5-inch negative produced a usable contact print without needing an expensive enlarger. Kodak’s Six-16 camera was moderately economical but featured a high-quality 126-millimeter wide-angle lens which captured images on par with the more professional 4-inch by 5-inch cameras of the day. Aircraft and railroad enthusiasts loved the format, which soon became the standard for trading negatives. Kodak discontinued its Six-16-camera line in 1948 and phased out the film stock they used in the mid-70s.

In the heart of St.Louis, Lambert Field is presently the largest and busiest airport in all of Missouri. Even back in the 1950s, Lambert offered ample opportunities for aviation photographers. For starters, it was home to the Missouri Air National Guard, to Naval Air Station St.Louis, and the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation. But many airliners and general aviation types also passed through St. Louis. Capturing decent images of these aircraft with a Six-16 was no easy feat, as Ostrowski recalled: “To get a full frame shot of a taxiing aircraft with a Six-16 camera, you needed to be very close to the taxiway. There was a perfect spot next to the Ozark Air Lines hangar we frequently used for our photography outings. We walked out to the taxiway, took the photograph, and returned to the hangar.”

Continuing, Ostrowski noted: “Some Navy reserve pilots got so used to us that they would stop their airplanes, let us get our pictures, and then be on their way! We got to be good with our manual Six-16 cameras. You learned how to judge distance for a sharp focus and developed a feeling for tracking a moving airplane using the waist-high viewfinder, which was no bigger than your thumbnail. It was an easy camera to use once you got used to it.”

The Lambert Field negatives that Ostrowski began trading with other aviation photographers eventually caught the attention of Major Eugene “Gene” Sommerich.

Gene Sommerich, a St Louis native, was an Air Force fighter pilot who flew P-38s in World War II and F-86s in Korea. In 1953, he also flew the MiG-15 that North Korean pilot No Kum-Sok used to escape to South Korea. “Gene Sommerich was my early mentor,” recalled Ostrowski. “He was a well-known Six-16 shooter and was interested in the images I took around Lambert Field. He looked at my negatives and suggested how I could improve my photography. I regret not meeting Gene in person, but I have never forgotten his kindness, which I have paid forward to many younger photographers over the years.”

Sommerich instructed the budding Six-16 shooter in removing and adequately cleaning the camera’s lens for sharper images. He also suggested modifying the camera’s winding knob. Dave Ostrowski relates, “You only get eight shots per film roll, and many times you needed to shoot quickly to get the shot. Kodak designed the Monitor with a flush-mounted film winding knob, making it difficult to grasp when advancing the film rapidly. This limitation was overcome by simply inverting the knob, which raised it about a quarter of an inch off the camera’s body.”

By 1956, sixteen-year-old David Ostrowski was fairly well-established in aviation photography. That same year, the now legendary aviation photographer Bill Larkins sent him a letter asking him to join an organization he was forming named the American Aviation Historical Society (AASH). As member number 27, Ostrowski is a lifelong AAHS supporter.

After High School, Ostrowski attended the famous Parks Air College in East Saint Louis. He then had a long and exciting career working for the Army Aviation Command Systems (St. Louis), Naval Air Test (Patuxent River, Maryland), The Army Material Command (Alexandria, Virginia) and finally, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in Washington, DC. Upon retirement from the FAA, he became the Editor for the highly regarded Skyways magazine [not be confused with the in-flight entertainment publication]. Along the way, he collected all things aviation. He is also well known for his generosity in helping other aviation enthusiasts pursue their interests. When asked about his fond memories of being a Six-16 photographer, Ostrowski remarked contentedly, “It was an excellent way to get to know many good people who became friends for life.”

Today David Ostrowski is busy organizing the small mountain of Six-16 negatives he exposed and received in trades. He intends to donate this material to various institutions so that future generations can gain understanding for what it was like to be one of the MASTERS OF THE KODAK SIX-16

Author’s Note: The inspiration for this piece came from Brian Baker’s article The 616 Camera Aircraft Photographers, which appeared in the January 2017 issue of BEAM magazine. I hope that the Vintage viation News readership will help further document the many unsung photographers who helped capture our rich aviation history. – A.Kevin Grantham

Very nice article, always interesting to read about the early photographers and the challenges they went through. As I was friends with WTL, he used to tell me that to get some of his shots on military bases, he would walk out with his camera under a long overcoat. Pop it open, get his pictures, and then get out of there quickly.

Great to hear from you Roger, and thanks for the fascinating detail. Really glad you enjoyed the piece, and I am sure both Kevin and Dave will be too. Cheers, Richard