by John M. Caratola, PhD.

From the very beginning of organized warfare, men in combat have adorned their weapons, shields, or regalia with symbols, designs, or art work that expressed either individuality or group affiliation. Weapons and equipment used by the Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, medieval knights, and even soldiers fighting in today’s conflicts had some kind of artwork or symbols signifying a cultural identity, affiliation, or individuality. In the early Twentieth Century, a new form of artwork began to appear that arguably reached its zenith during World War II. With the advent of airplanes and their presence over the battlefield, the large surface areas of these new machines provided another opportunity for expression by men in combat. Nose art was a form of expression that applied to thousands of aircraft from both the Allied and Axis air forces as they adorned their mounts with colorful and distinctive graphics.

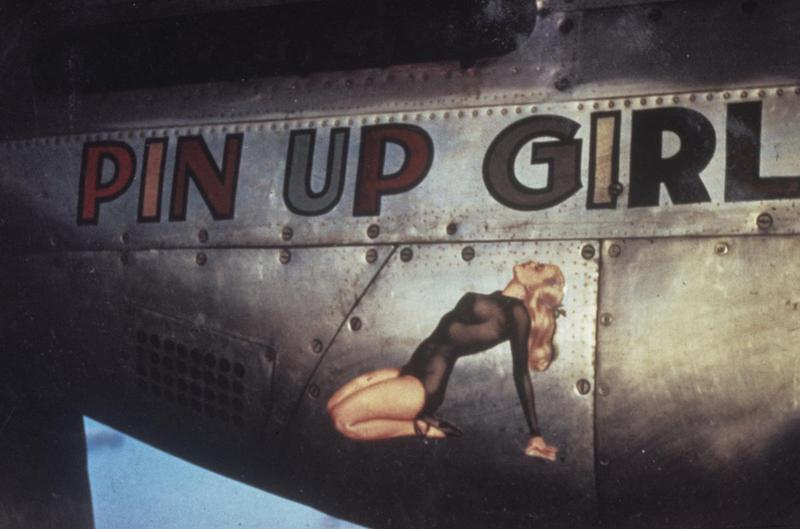

The term “nose art” does not necessarily mean that the graphic was on the front of the aircraft. Many crews used various parts of the plane as their selected “canvas.” While most were indeed on the front of the plane or by the engine or cockpit area, some art was on the tail, fuselage, or even the wings. In reviewing images of nose art it is hard to define any set of rules or convention. The tone, temperament, and content varies from unit to unit and from country to country. However, there are a few common trends as most art reflected themes of patriotism or nationalism, popular culture, unit pride, and personal expression/accomplishment. For larger aircraft, the art might reflect the character of the crew. However, depictions of women were most often the subject of the art form. Living in a mostly all-male environment and separated from the women they loved, it has been estimated that over half of US Army Air Forces (USAAF) nose art during the war was based upon the female form and in some kind of “cheesecake” pose.

During World War II much of the nose art was influenced by two contemporary artists of the day. The first was Alberto Vargas, a Peruvian born painter who studied art in Europe before World War I. Traveling to America, he started his career at the Ziegfeld Follies and Hollywood during the interwar years. Renditions of his idealized depictions of women in seductive poses were seen on many aircraft. Additionally, his “Vargas Girls” series became a staple in many post-war magazines to include Esquire and Playboy. In addition to Vargas, Gil Elvgren, a commercial artist in Chicago, became known as the “Norman Rockwell of Cheesecake.” Like Vargas, Elvgren’s work was also copied by many military artists and could be seen in both theaters of the war.

While seductive poses of females are viewed as sexist by today’s standards, it would be difficult to find any nose art of that era that could be considered pornographic. (In the author’s opinion.) While many of these depictions were certainly seductive and overtly suggestive, these were still military aircraft subject to inspection and oversight by commanders. In one instance, a topless woman adorned the nose of a USAAF bomber. When it arrived at an intermediate staging base on its way overseas, a local commander ordered the crew to cover the woman’s exposed breasts. The crew chief dutifully obeyed the commander’s orders…with water based colors. As a result, upon entering precipitation after take-off, the art work returned to its original topless form!

Additionally, not all female themed art was sexual in nature. Some art suggested respectful tones for women as they mentioned mothers, sisters, or other family members. The first nuclear bomber, the “Enola Gay” is one of the more popular examples of this respectful tone as it referred to pilot Paul Tibbets’ mother. This was also true for Medal of Honor recipient Colonel Neel Kirby who named his P-47 “Fiery Ginger” after his red-headed wife. Similarly, Major Rich Turner named his P-51 “Short Fuse Sallee” after his wife. (However, he shortened the name to “Short Fuse” after they divorced!) America’s top ace was equally respectful as Major Richard Bong’s named his P-38 “Marge” in honor of his fiancée, with her accompanying portrait.

Women weren’t the only source of inspiration. Cartoon themed artwork was popular and included Disney, Looney Tunes, and many comic strip characters. Thumper, Jiminy Cricket, Bugs Bunny, Donald Duck, Lil Abner, and Steve Canyon were only a few of the cartoon figures found on aircraft. One character that was especially prevalent was artist Milt Caniff’s creation “Miss Lace.” This scantily clad and sultry siren, with a penchant for enlisted men over officers, was a popular icon and introduced in a wartime comic strip series entitled “Male Call.” Miss Lace inspired art was easily be found on aircraft in both theaters. Additionally, the international appeal of Mickey Mouse was universally popular as the rodent was found on many Luftwaffe aircraft and on ‘General der Jagdflieger’ Adolf Galland’s personal ME-109.

Another form of nose art depicted the accomplishment of the crew. Many multi-engine bombers included a tally of the number of missions flown and/or the number of enemy fighters claimed. Single engine fighters often depicted the number of fighter sweeps accomplished, top cover missions conducted, or escort duties completed. Perhaps the most celebrated accomplishment art was the “kill” markings fighter pilots painted on the side of their mounts for victories over enemy aircraft. Taking many forms and designs, many photographs had the pilot posed next to the tally board painted on the fuselage. Some pilots only counted enemy aircraft destroyed in the air, while others included strafing kills in their tally. Pilots who were assigned primarily close air support missions sometimes tallied the number of trains destroyed, troop concentrations attacked, or enemy trucks wrecked.

One of the more interesting kill marking score boards belonged to 1st Lieutenant Louis Curdes’ on his P-51 named “Bad Angel.” What is unique about it was that not only did it include a victory marking from all three Axis powers (He was one of three pilots with this distinction.), but also included an American kill! On February 10, 1945, Curdes found a USAAF C-47 lost and attempting to land on a Japanese held airfield on the island of Bataan. Unable to contact the lost aircraft by radio, he tried unsuccessfully to thwart its landing and finally decided to shoot out the C-47s engines, forcing it to ditch in the water. While all aboard survived the friendly attack, what makes the story even better is that his date from the night before, a nurse, was on the C-47 he shot down!

Perhaps some of the best renderings of nose art were painted by commercial artists who joined the military after America’s involvement in the war. The 834th Bomb Squadron, called the “Flying Zodiacs,” was fortunate enough to have one of these professional designers. Corporal Phil Brinkman was assigned to the B-24 squadron and painted the unit’s aircraft with a sign of the zodiac with some accompanying artwork. Each example was beautifully depicted. Unfortunately, the only zodiac sign not finished was Taurus (the bull) as every time he started the design, the plane failed to return.

Another professional artist that created very distinctive nose art was Staff Sergeant Sarkis Bartigan who often used the whole of the B-24’s large nose area as the canvas. In one example of his work he used the bomber’s entire fuselage side. Entitled, “The Dragon and His Tail,” this unique piece had a green dragon clutching a nude woman in its claws with the animal’s tail snaking all the way to the rear turret of the bomber. Unfortunately the original artwork was destroy when the bomber was cut up as postwar excess.

However, most art work was created by men in units who simply enjoyed painting and drawing. Many artists made a few dollars on the side with their skills, with the price depending upon the intricacy and difficulty of the design. Artists also received further benefits in terms of rations or alcohol. Still others more pragmatically used their talent as a way to get out of additional duties.

Understanding the importance of nose art to crew and unit morale, by August 1944, Army Air Forces Regulation 35-22 actually encouraged the practice. In this directive, the USAAF “encouraged [the practice] as a mean of increasing morale.” However, the Navy Department took a dim view of the practice and had regulations against it except for squadron or unit insignia. However, a review of US Navy and Marine Corps photos from the time do indeed show a significant number of naval aircraft with art work of the same character as their USAAF counterparts. The application of naval service nose art was probably relative to the unit’s distance from a higher headquarters and inspection.

In sum, American nose art during World War II is an important piece of this nation’s military history. It also serves as a reflection of American popular culture at the time. These colorful depictions were in many cases-standalone pieces of art in their own right and were masterfully rendered. Perhaps more importantly, nose art serves as a lasting expression of the brave men who flew these machines while they provided a bit of whimsy and a small reminder of home at a dark and dangerous time.

Related Articles

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.

Please do not forget “Glamorous Glennis” and “Old Crow”–the most famous P-51s of all !!!! DMD