The following is an edited version of Kevin “K5” Michels’ article on how the wartime manufacture of Boeing’s B-17 Flying Fortress adapted to get the best and most up-to-date variants of the aircraft to combat crews in as fast a time as possible. It focuses in particular on the inclusion of the so-called ‘Cheyenne tail’ into the aircraft’s design. The article was originally produced for the Commemorative Air Force Gulf Coast Wing’s newsletter, Cowl Flaps, and is reproduced here with permission. It makes for fascinating reading, and we feel sure that you will enjoy it!

Setting the Record Straight – B-17 Modification Centers

by Kevin “K5” Michels

While it is common knowledge that three different manufacturers produced Boeing’s B-17 Flying Fortress during WWII – Boeing, Douglas, and Vega (Lockheed) – the existence and purpose behind the Modification Centers are less well known. So what were these facilities and why were they necessary? We will now dive into this fascinating subject and, hopefully, dispel a myth or two along the way…

It is arguable that any B-17 aficionado will know what a ‘Cheyenne Tail’ refers to. Some may even proclaim that any B-17G sporting such equipment received those modifications in Cheyenne, Wyoming, but this is a common, though oft-repeated mistake. Other than for a short period of the production run, most B-17Gs received their ‘Cheyenne’ tails at the factory, not in Cheyenne. If that surprises you, then please stick with me as the history of the Modification Centers is about to unfold…

THE PROBLEM

During the early period of B-17 manufacture, most airframes within any given production variant were pretty much identical. For example, a B-17B was a B-17B, and there was little-to-no difference between the first B-17D to roll off the factory line and the last. This same premise held true through the B-17E, which had few significant differences (with the exception of the ventral turret) throughout its production run. With the advent of war, however, a flood of combat lessons resulted in a steady stream of engineering changes which required immediate implementation. As such, both the B-17F and B-17G varied significantly over the course of their production periods. These constant changes led to the bizarre situation in which an early-model B-17G had more in common with a late-model B-17F than with a late-model ‘G. To help keep track of these changes, and especially to assist maintenance personnel, each factory would identify a subset of B-17s with entirely identical manufacturing standards by grouping these aircraft into “Production Blocks”. The Commemorative Air Force’s Flying Fortress known as Texas Raiders, for example, left the factory as a B-17G-95-DL, where “-95” designates the aircraft’s ‘production block’ while “DL” means that Douglas Aircraft assembled the airframe – but more on that later.

The initial challenge involved determining how to implement all of these “must-have” engineering changes into a “produce as many as possible” production line. Anyone who has ever worked in production knows that line changes are the enemy of efficiency; the more changes you make, the lower your production rate. So, how should one proceed given these opposing goals? The bottom line was that combat crews needed as many of the best available aircraft to have a fighting chance against the enemy – i.e. neither goal could be sacrificed, thus placing the factory between the proverbial “rock and a hard place.”

Initially, aircraft manufacturers tried to implement every engineering change directly into the production line. While this achieved the first goal of producing aircraft which were both combat-ready and state-of-the-art, it failed the second goal by slowing production to unacceptable levels. Clearly, another solution was needed – and right away.

THE SOLUTION

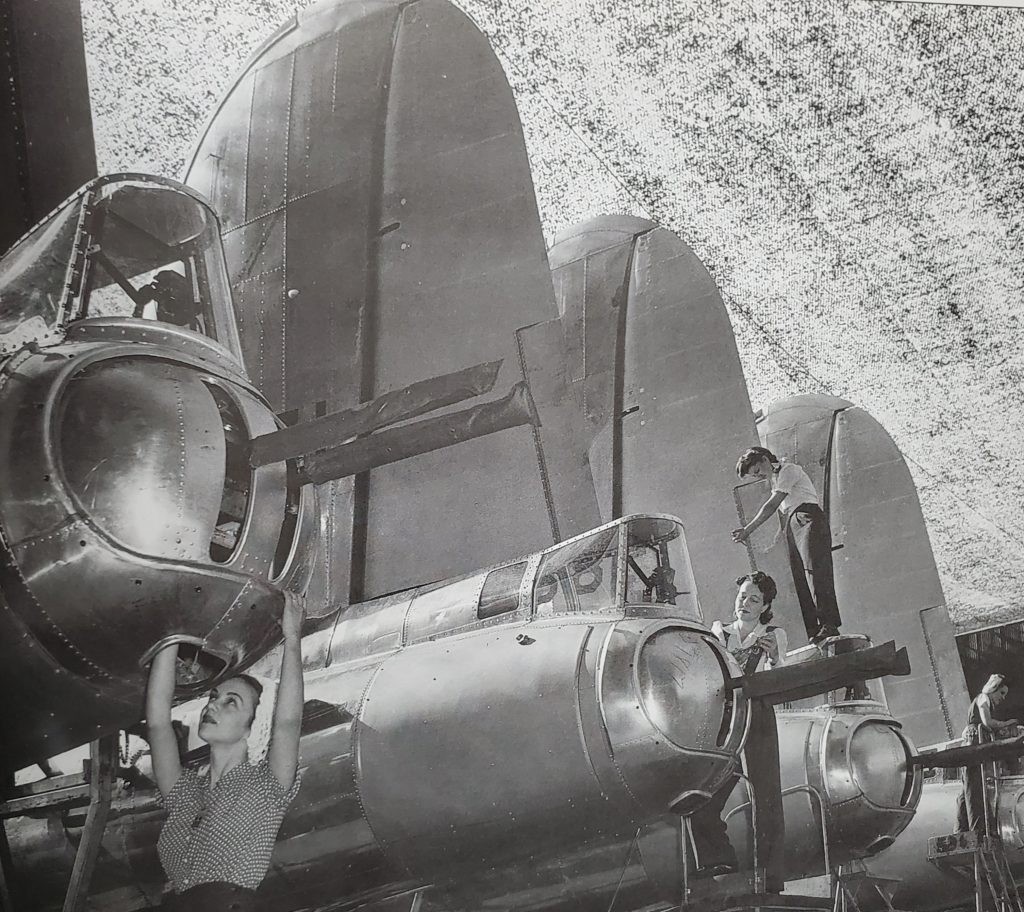

As already intimated, the twin goals of maximizing both quality and quantity usually result in the sacrifice of one desire for the sake of the other. However, when one can expend both treasure and labor in near-unlimited amounts, it is possible to maximize quantity and quality simultaneously. WWII was a critical moment in history where such a situation presented itself. As such, manufacturing was maximized by mass producing essentially identical aircraft, and then sending them to Modification Centers to upgrade them with the most current engineering modifications. This solution accomplished both goals simultaneously.

Now that a workable solution to maximize both quantity and quality had been implemented successfully, factories still needed a way to integrate engineering changes into production lines over time. Otherwise, even the Modification Centers would become overwhelmed with a never-ending stream of new engineering changes, creating a bottleneck which could eventually starve frontline units of combat-ready aircraft. Therefore, a factory’s technical leadership would periodically gather groups of engineering change orders together which, when carefully considered and introduced, could efficiently adapt a production line to incorporate necessary manufacturing updates with minimal impact to throughput. Each group of aircraft which resulted from a given set of engineering changes would receive its own unique “Production Block Number.” Each Production Block usually included between 100 and 200 airframes, but this could vary depending upon the situation.

After a factory integrated a technical order into their production line, the Modification Centers no longer carried the responsibility for including it and could therefore dedicate their resources towards affecting newer engineering updates. Once this system of implementing production changes came about, most other U.S. aircraft factories adopted it too, not just those producing B-17s. Even though the process was wildly expensive and grossly inefficient in terms of labor and even material, it enabled the US aircraft industry to produce and deliver a staggering 300,000 service-ready aircraft to the military during the war – and that played a critical role in defeating the enemy.

At its peak, the US Army Air Forces had 24 Modification Centers spread across the United States; most of these facilities were qualified to work on multiple aircraft types. Interestingly, some of the Modification Centers were positioned right beside the aircraft factories themselves, while others were further afield, requiring newly-built aircraft to undertake ferry flights to receive their upgrades.

The following five Modification Centers specialized in B-17s:

Cheyenne, WY – United Airlines (UAL)

Dallas, TX (Love Field) – Lockheed Aircraft

Denver, CO – Continental Airlines

Long Beach, CA – Douglas Aircraft

Tulsa, OK – Douglas Aircraft

Getting an aircraft from its factory into combat was no small task. The usual path for a B-17G involved the following:

1) Production at the factory.

2) Delivery to a Modification Center where the latest engineering changes were installed.

3) A pilot, often a WASP, then flew the now state-of-the-art aircraft to an embarkation point within the Continental United States

4) An Army Air Forces ferry pilot then flew the aircraft overseas to the combat theatre.

5) Local commanders would order whatever final modifications they deemed necessary.

6) The aircraft would then enter combat duty with its assigned unit.

Although I do know that Boeing was able to assemble 16 Flying Fortresses per day at its peak, thus far I have been unable to ascertain the length of a typical B-17 production cycle. Determining the actual time it took to build a single B-17, from-beginning-to-end, has also proved elusive. Once it rolled off the production line, a typical B-17 usually found an assignment to a combat squadron within 45-90 days. This is but a small example of what it took to defeat the Axis powers though. In total, the war was a massive team effort between the United States and our Allies; it involved participation from almost everyone in the aptly-named Greatest Generation. Such an all-encompassing international effort has yet to be duplicated…

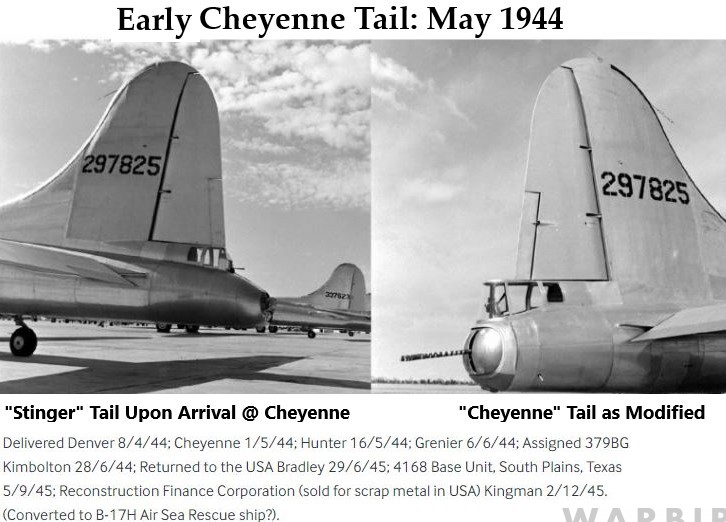

THE CHEYENNE TAIL

The first B-17Gs came equipped with the iconic “Stinger” tail (a.k.a. “steeplechase”); the later “Cheyenne” tail (a.k.a. “pumpkin”) emerged as just one of the hundreds of wartime engineering modifications to the Flying Fortress. The UAL Modification Center in Cheyenne, Wyoming began installing Cheyenne Tails on February 15th, 1944, with Boeing-built B-17G 42-97261 being the initial airframe to receive the upgrade. Throughout that spring and into the summer, UAL Cheyenne was busy installing these new tails along with several other engineering modifications.

However, by June 1944, Boeing had incorporated the ‘Cheyenne Tail’ into their B-17G-80-BO production block, with Douglas doing the same with their B-17G-50-DL production block. Vega followed suit that July, introducing the new tail design into their B-17G-55-VE production block. With their workload now lightened, the UAL Cheyenne Modification Center moved on to newer engineering modifications.

WHAT WERE ENGINEERING CHANGES?

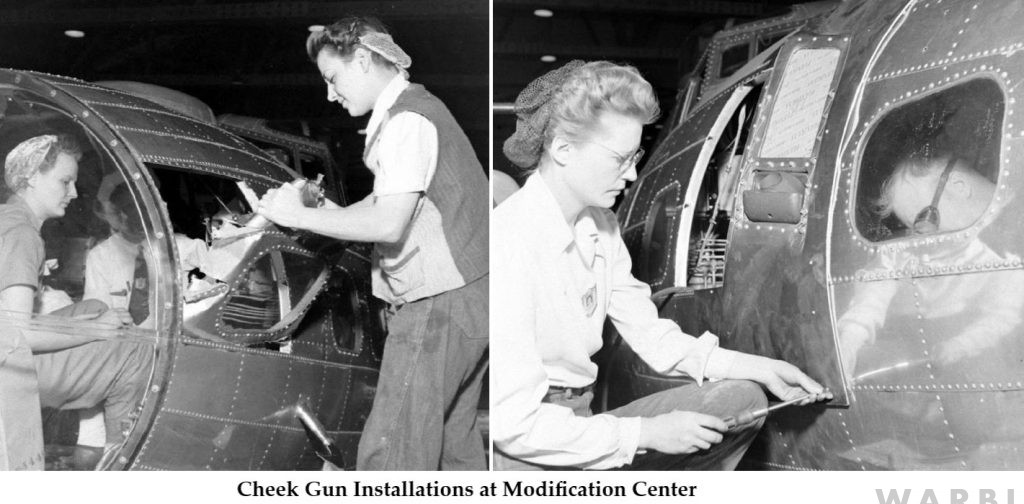

Engineering changes simply involve upgrades to an aircraft design with the aim of making it a more effective tool. Some of these modifications were big and highly noticeable, while others were more subtle and required detailed knowledge to locate. Changes originated from many sources, with the most important input coming, of course, from front-line combat units which needed real solutions to real problems as soon as possible. However, some engineering changes emerged directly from the Modification Center teams themselves. For instance, many claim that UAL Cheyenne first came up with the Chin Turret, Cheek Gun Blisters, and Cheyenne Tail. Meanwhile, stateside commanders and factory aeronautical engineers were also proactive in their endeavors to solve problems they perceived in the design. Combat units sometimes received these upgrades enthusiastically, but this wasn’t always the case, and there were plenty of examples of either situation. Indeed, on occasion, an engineering change was added at one stage of production, only to be switched out or further modified later. And finally, some engineering changes were dependent upon the region where a specific aircraft was due to serve.

Although the goal was to have each aircraft fully combat-ready upon its delivery to a unit in the field, this sometimes failed to occur. Instead of a frontline unit, such aircraft often went to a depot in the rear area where additional modifications could take place. Sometimes such modifications involved stripping out equipment considered ineffective or excess weight, while others could involved the addition of new equipment to fulfill a local commander’s requirements.

Engineering changes were frequently installed retroactively to combat aircraft already in the field. One famous example of such a change includes deployed Republic P-47D Thunderbolts having their propellers changed from the “needle-blade” design to the “paddle-blade”. This was an example of a stateside aeronautical engineer’s proactive fix to a problem which had a profoundly positive effect for the aircraft and their crews. For a pilot’s perspective on this event, Robert S. Johnson’s brilliant book “Thunderbolt” covers it quite effectively.

B-17G’s, like all WWII combat aircraft, were a work in progress throughout the conflict. As such, one could expect to find all manner of variations in a detailed comparison between two aircraft of the same variant. Two B-17G’s produced just a few months apart, for example, could differ in a number of ways. Most of us have heard or read stories from combat veterans about their particular B-17s. Some of these stories inevitably conflict with one another on certain details. But since each veteran’s story evolved from their own personal experiences with the equipment they had on hand and under the combat conditions they faced, it is no surprise that their stories can have differences.

PRODUCTION BLOCKS

If you are interested in details for a particular B-17 production block, the link HERE is an excellent resource. Keep in mind that each factory managed its own production, so their modification implementations could occur over different timeframes. Furthermore, please note that there is no correlation between production block numbers from one factory to another. For example, Boeing’s -60 production block is unrelated to the -60 production blocks at Douglas or Vega. Moreover, since the overriding goal during WWII was getting combat aircraft properly outfitted and into the hands of combat crews as soon as possible, proper paperwork was sometimes late or non-existent. This means that some of the information in this link may not be 100% accurate even though it is the best available data on the subject.

To learn more about the B-17 Flying Fortress known as Texas Raiders and the CAF Gulf Coast Wing which operates her, please visit www.b17texasraiders.org

Related Articles

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.