The Nature of WWI Aircraft – Javier Arango & Philip Makanna

Review by Richard Mallory Allnutt

A magnificent new book has arrived which will prove essential reading for anyone interested in WWI aviation:

The Nature of World War I Aircraft – Collected essays by Javier Arango with Photography by Philip Makanna

Populated with richly informative, beautifully written prose from the late and much-missed Javier Arango alongside marvelous images by the legendary photographer Philip Makanna, this book describes Javier’s experiences resurrecting, flying and testing numerous Great War-era aircraft types. It is also filled with the detailed, yet clearly explained engineering and historical knowledge which Arango gained during that process. Perhaps most importantly, Arango’s explanations of his flight testing serve as a literal bridge to the past, opening a window of understanding for more properly interpreting the contemporary stories of WWI flyers.

A Harvard-trained science historian and highly experienced pilot, Javier Arango possessed a long-held passion for the early years of powered flight and, in particular, the aircraft which saw service during WWI. This fascination proved so powerful that he dedicated much of his adult life towards learning how these elegant, but ever-so-fragile war machines were built and flown. Powered flight was barely a decade old in that era, and Arango quickly understood how contemporary aircraft designs were mostly the result of iterative experimentation rather than careful study and mathematical precision; aircrew being the guinea pigs in this process!

But precious few original Great War-era flying machines remain, with barely a handful capable of flight. Furthermore, little documentation which describes the methods used to build these aircraft survive, nor the reasoning behind many engineering choices. And as with so many aspects of history, time has a way of amplifying myth and mistruth, which sometimes obscure the actual facts beneath them. Arango realized that to better understand WWI aviation he had to dig in to primary source material on the matter rather than rely on more recent interpretations. But after sifting through countless contemporary accounts of those who had built and flown these machines in WWI, Arango also arrived at the belief that the only way to gain proper understanding for their experiences was by going through the demanding process of manufacturing and flying faithful replicas of their aircraft – powered by authentic engines. Indeed, as Arango stated:

“The knowledge that comes from direct experience transcends the particular object and provides insights into history in general.”

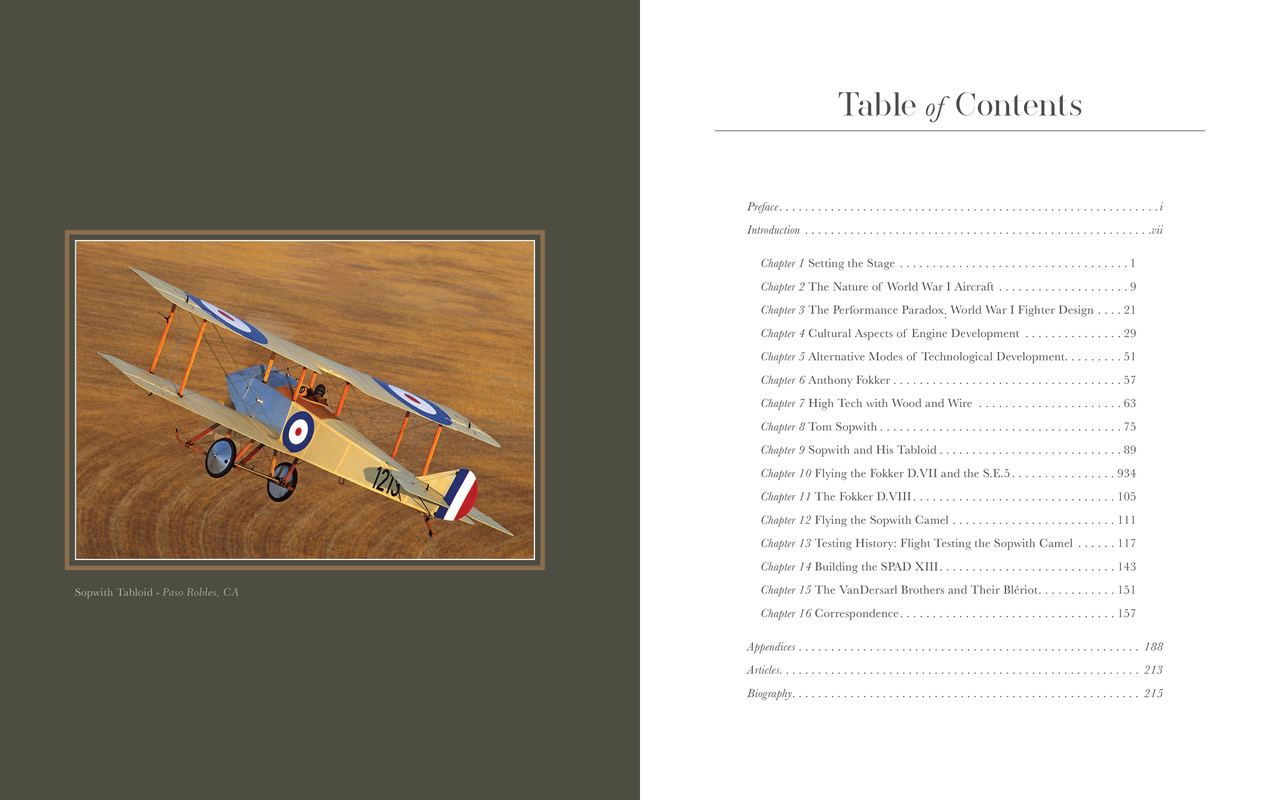

Therefore, collaborating with master craftsman Chuck Wentworth, Javier Arango endeavored to reproduce (and fly) some of the best and most authentically-built examples of 24 different WWI aircraft designs. Furthermore, with Richard Galli, he organized the precise reproduction of ten 110hp LeRhone rotary engines to power some of these airframes, while using refurbished originals for most of the others.

Arango set about evaluating his aircraft to learn more about them and, as a consequence, those who once flew them a hundred or so years earlier. For instance, while performing a series of instrumented flight tests in his Sopwith Camel, he was able to debunk a number of long-held, but mistaken beliefs about the design. He also discovered a framework for interpreting how pilots described the aircraft during its heyday, writing eloquently about his discoveries as follows:

“A Sopwith Camel in flight has a mixed nature, half human and half machine. WWI pilots became part of the machine… As we compared what pilots reported to what we actually measured [in our flight testing], it became evident that understanding their words required a context we lacked. Even though WWI pilots were speaking English, they were using a different language from our own, a century later…

Our vocabulary includes the terms roll, bank, turn, turn rate, spiral, etc. WWI pilots did not have standardized terminology, so their words did not have a constant meaning. They belonged to one of the first generations of pilots, so they were inventing the terminology as they were experiencing it… they often resorted to exaggerations in order to emphasize a point. Context is critical to understanding, and, unfortunately, the written sources simply assume a common context without defining it explicitly… Testing the Camel provided us that context, with a translation mechanism allowing us to reinterpret the WWI pilots’ language more precisely…

WWI airplanes can act as a Rosetta Stone, helping us understand the past by deciphering the meaning of their pilots’ words. Restoring the airplanes, working with them, and flying them also teach us that these airplanes were very much extensions of their pilots. The relationship between a pilot and his flying machine in WWI was still symbiotic. The capabilities of each airplane depended on the skill of its pilot, and what the pilot dared to do depended on the characteristics of his airplane.”

And this is but a small flavor of the insight you will find in this extraordinary book. Other than those who saw combat in the skies over Europe and the Mediterranean during the Great War, it is hard to imagine more than a handful of people over the past century who had a greater understanding than Javier Arango for the history, technology and flight characteristics of WWI aircraft, nor the ability to so ably describe them.

[Author’s note: From a personal perspective, reading the book gave me greater appreciation for what two of my own great uncles experienced as pilots with the Royal Flying Corps during WWI. I will always be grateful to Javier for that.]

Sadly, Arango’s quest for the truth eventually cost him his life when the elevator malfunctioned on his Nieuport 28 in April, 2017. While the replica Great War aircraft in his collection now lie dormant, and his two ultra-rare originals have moved to the Smithsonian, Arango’s wife, Antonieta, was determined to share the vital knowledge about WWI aviation which Javier had uncovered. With the collaboration of his friends and colleagues, she collected Javier’s essays and numerous other writings together into this book. It is an exceptional document, and a worthy legacy of Arango’s work.

The book itself is superb in every regard, from its layout design through to the quality of its production values. With a print run of only 1,000 copies and a price point of just US$30, it is sure to sell out very quickly. It is on sale exclusively through Philip Makanna’s Ghosts website at the link below.

The Nature of World War I Aircraft – Collected essays by Javier Arango with Photography by Philip Makanna

Richard Mallory Allnutt's aviation passion ignited at the 1974 Farnborough Airshow. Raised in 1970s Britain, he was immersed in WWII aviation lore. Moving to Washington DC, he frequented the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum, meeting aviation legends.

After grad school, Richard worked for Lockheed-Martin but stayed devoted to aviation, volunteering at museums and honing his photography skills. In 2013, he became the founding editor of Warbirds News, now Vintage Aviation News. With around 800 articles written, he focuses on supporting grassroots aviation groups.

Richard values the connections made in the aviation community and is proud to help grow Vintage Aviation News.

Thanks for posting this book review, I placed my order for it! Cheers and Happy New Year!!

Most impressive.