Between the late 1800s and early 1900s, a period of great technological growth occurred within the United States. One of the industries to experience the most advancement in such a short period of time was that of optics and photography. In Rochester, New York, a technological pioneer by the name of George Eastman led the charge to establish the consumer photography industry. In 1888, Eastman unveiled the Kodak camera to the world. Pre-loaded with film, this camera made taking photographs more accessible for the general public. On May 23, 1892, Eastman Kodak incorporated. For most of the 20th century, this Rochester based company would be a leader in producing cameras, film, and photographic equipment.

When war comes calling, the countries involved turn to their industrial leaders to produce the goods that will help them fight. In 1941, when the United States was thrust into World War II, the US government began reaching out to the companies they knew could help them the most. Eastman Kodak was high on the list of manufacturers on the government’s priority list. The US military had a strong need for photographic equipment, for reconnaissance and public-relations purposes. Furthermore, Kodak’s advancements in optical technology made them an attractive company to have produce “widgets” for the war effort. You see, the US military had an ace up its sleeve in the fight against the Axis powers, one that could prove to be deadly accurate with the proper construction.

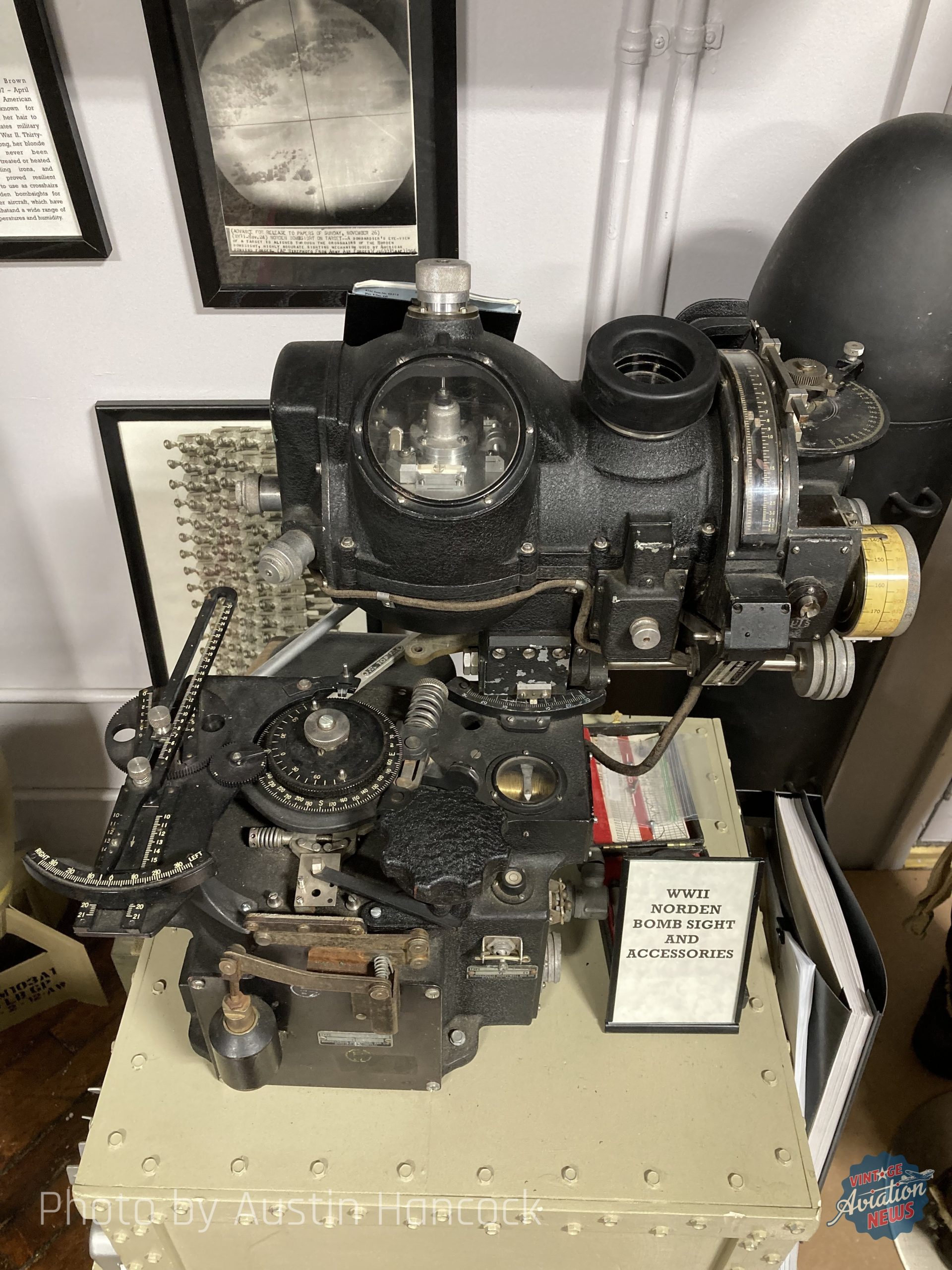

As World War II progressed, the United States was focused on using daylight bombing raids to destroy German targets of interest. As opposed to the British preference of night bombing, these daylight strikes were flown with the intention of more precise bombing and less civilian casualties. Within the nose of the B-17 and B-24 bombers flying these raids was a top-secret device which aimed to improve the accuracy of the bombs being dropped. Known as the Norden Bombsight, this technological achievement was intended to give Allied bombers an advantage. First conceptualized in the 1920s, the Norden Laboratories Corporation developed the bombsight over the course of many years. They experimented with different prototypes, and ultimately developed the Mk. XV. After many negotiations between the US Army Air Corps, the Navy, and other optical manufacturers, the Norden Bombsight was officially adopted into Allied service.

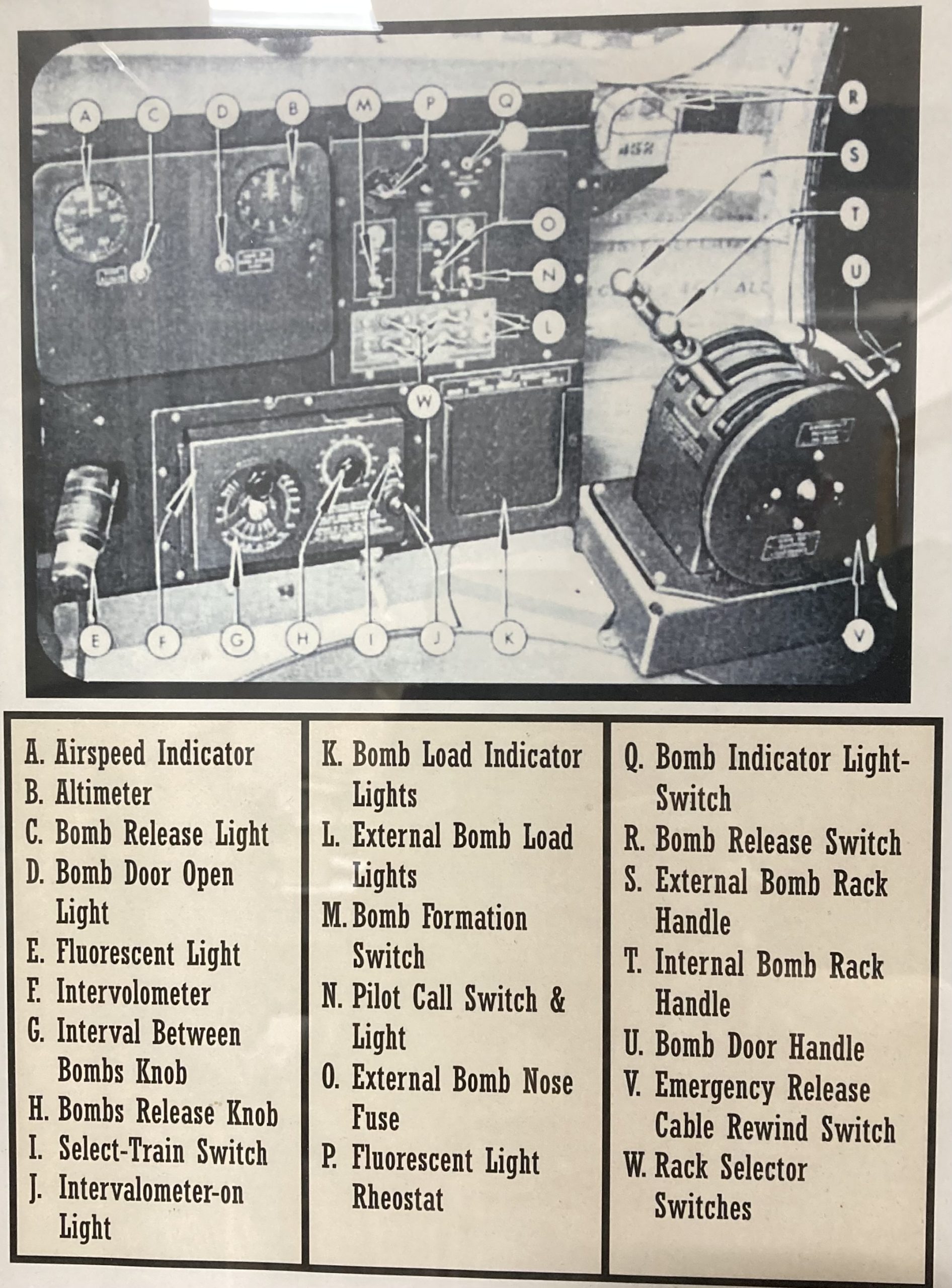

In 1942, the Norden bombsight was augmented with Automatic Flight Control Equipment (AFCE), via Honeywell Regulator. This connected the bombsight to the aircraft’s internal autopilot system, meaning that the bombardier could now control the aircraft with minor movements during a bomb run. There was a switch that transferred control from the pilot to the bombardier, and back. At the time, this was cutting-edge technology. In addition to the claims of superior accuracy, the Norden was a closely guarded secret by the United States. The US government felt the Norden bombsight to be so crucial that bombardiers were ordered to destroy the device if the aircraft they were on should be brought down, for any reason. The Allies did not want the enemy to get their hot little hands on it. Over the years, claims about the unmatched accuracy of the Norden sight have been disputed. The consensus is that although it didn’t match the accuracy claims from the factory, it did serve an important role by delivering bombs within a certain tolerance. This likely led to more successful strikes and saved lives.

Back in Rochester, New York, as World War II was in full-swing, so too was Eastman Kodak’s research and production. During the war, many manufacturers of military goods subcontracted with other companies in the same industry. This allowed resources and workload to be evenly split, leading to greater production efficiency overall. Norden knew that Kodak was proficient in creating optical devices, due to their history with producing photographic equipment, so it was the perfect working relationship. Norden contracted Kodak to create internal optical components for their bombsight. To this day, it is largely unknown exactly what components of the sight were made by Kodak. Workers were sworn to secrecy, and often never even told what the purpose was of the part they were making. This author’s own Grandmother worked for another Rochester based company in World War II, Bausch & Lomb. Also producing parts for Norden, B&L employees were not told exactly what they were making, only that it was highly secret and not to be discussed outside of the factory’s walls.

On the northeastern edge of downtown Rochester, on St. Paul Street, sits a menacingly large empty building. Once a staple in the Kodak industrial complex, the Hawk-Eye building now sits abandoned. The facility was named after the famous Kodak Hawk-Eye camera that was produced there. The building waits for its developer to either decide on a plan for revitalization, or to sell it. Within the walls of this epic, albeit run-down building, optical components of the Norden bombsight were manufactured, in total secrecy to all including those who worked there. After World War II, many other top-secret military projects were developed here. Hawk-Eye is truly a historical landmark, even though we may never know the exact “widgets” created there. Though the building may be worn, and the Kodak Company a fraction of what it used to be since the advent of digital photography, Hawk-Eye still stands as a symbol of American ingenuity and fortitude.