By Adam Estes

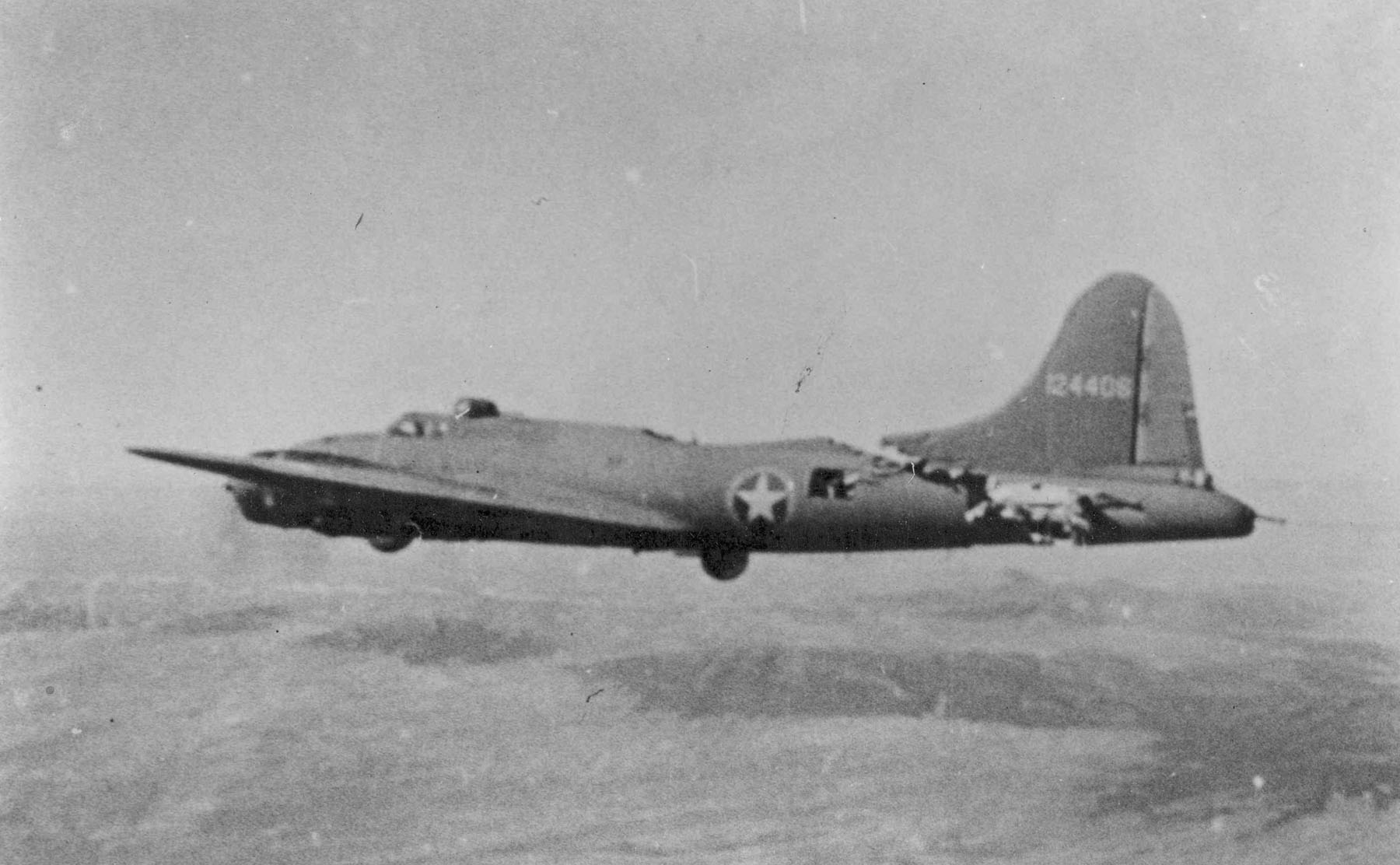

In many books and magazines on the history of WWII, few photographs of the venerable B-17 Flying Fortress are more prominent in the public eye than this striking photo, showing a B-17 flying almost literally on the spit and prayers of its crew. Having been struck by a Messerschmitt Bf 109 in the skies above North Africa, it remained airworthy long enough to not only return to base in one piece but with no deaths or injuries among its flight crew. It is often used to illustrate the incredible durability of the Flying Fortress. Yet the story behind the photo has since taken on a life of its own that has only grown in the postwar years with nearly every retelling adding more and more fantastical details to the story. Today, however, we will get to the bottom of the story behind this famous photograph and reveal the truth behind the B-17 known as “All American.”

The oft-repeated version of All American story, as mentioned in our previous article from 2013, (The Real Story of WWII’s B-17 “All American” ) states that the crew of the All American flew with their bomb group to bomb the German docks at Tunis, Tunisia, where they were struck by a Messerschmitt Bf 109, but still managed to drop the bombs on target despite rushing air threatening to rip the tail off and return home to England. The photograph of their plane was taken by a P-51 over the English Channel, and the story goes further to state that the waist gunners were forced to use their parachute chords and even wreckage from the German fighter to fasten the remaining parts of the tail while the tail gunner had to stay in the swaying section of the aircraft to maintain its integrity with his body weight. This is the exaggerated version of the story told over the postwar years, as though it were a big game of telephone, but the real story is just as fascinating and equally full of heroic actions.

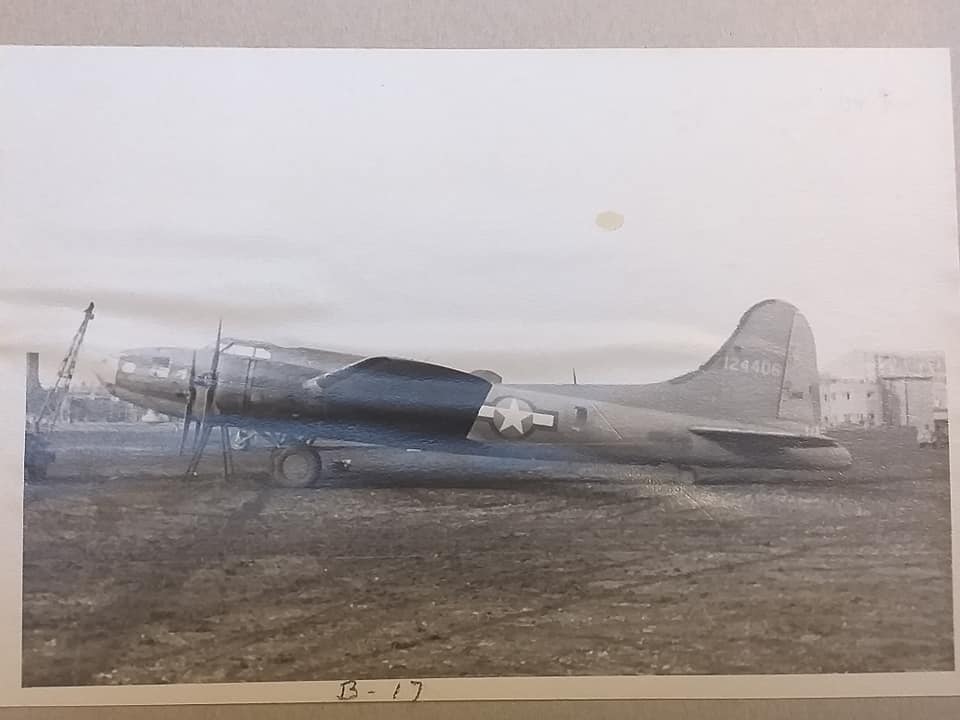

The B-17 All American began life like thousands of other B-17s: at Boeing’s plant in Seattle, Washington, being constructed as a B-17F-5-BO construction number 3091 and was accepted into the USAAF at Boeing Field (now King County International Airport) as serial number 41-24406. Immediately afterward, the plane began the long journey overseas to fight in Europe, being processed at the Middletown Air Depot of Olmsted Field, Middleton, Pennsylvania, before its transfer to the 327th Bomb Squadron, 92nd Bomb Group at Dow Army Airfield in Bangor, Maine. From there, they made their way to England via the North Atlantic route, with stops in Presque Isle, Maine, Gander, and Newfoundland, before arriving in Prestwick, Scotland on August 21, 1942, by Lt. Frank Ward and his crew. “After being reassigned to RAF Bovingdon (USAAF Station 112) in Hertfordshire, the crew and their plane were transferred to the 414th Bomb Squadron, 97th Bomb Group at RAF Grafton Underwood on August 24, 1942, before moving to RAF Polebrook.

The plane’s new crew in the 414th was led by Lieutenant Kendrick “Ken” Bragg of Savannah, Georgia, who had played football at Duke University during the 1938 season when the school’s team received the nickname of the “Blue Devils.” Upon receiving their new aircraft, Bragg and crew decided to name it “All American,” as the crew had come from all over the country before being assembled together, both North and South, but were now brothers in arms.

The 97th BG would continue daylight bombing raids into German-occupied Europe from Polebrook until November 1942, when the group became one of several units to be transferred to the newly-established Twelfth Air Force to support the Allied landings in French North Africa (Algeria and Morocco) codenamed Operation Torch. On November 20, 1942, All American set out from RAF Hurn, England, to Maison Blanche Airfield, near Algiers, before moving on to Tafaraoui, near Oran. By Christmas of 1942, the 97th Bomb Group was flying missions out of Biskra, Algeria. The men had to live in tents at the desert airfield, and was within range of German air raids, losing one of their B-17s, 41-24419 Virgin Sturgeon, to a German air raid on January 9, but the 97th would have their chance to strike back and play a part in forcing the Axis out of North Africa.

February 1, 1943: the crew of the All American are tasked with bombing the German-held ports at Bizerte and Tunis, Tunisia, just under 300 miles (482 kilometers) northwest of the base at Biskra. With the collapse of Vichy French rule in Tunisia, Tunis had become one of the last strongholds for the Germans and Italians in North Africa, and crippling the ports would curtail the effectiveness of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s already-strained logistics. All American and her crew would take position flying behind and to the right of the lead aircraft, 41-24477 “Flaming Mayme,” flown by the commanding officer of the 340th Bomb Squadron, Major Robert Coulter, while Flaming Mayme’s regular pilot, Lieutenant Jesse Wikle, took the copilot’s seat.

Though the pre-mission briefing stipulated that they would rendezvous with the 301st Bomb Group and their escort of P-38 Lightnings, the 301’s B-17s kept diverting from the briefed course to Tunis, which would have them approach from the southwest. Inside the Flaming Mayme, navigator Lt Ralph Birk advised Major Coulter to maintain a direct heading for Tunis to approach the city from the west. Major Coulter acknowledged this and led the 97th Bomb Group’s formation on this new course, leaving the 301st and the P-38s. On the way to the target, the formations had to fend off attacks from Messerschmitt Bf 109s, primarily of Jagdgeschwader 53, but these turned once the bombers were within range of the German anti-aircraft guns on the ground. Braving heavy flak, the 97th BG formation reached the target area, and have successfully dropped their bombs from 20,000 feet, the formation plotted a new course back to Biskra.

It was at this point, though, where two Messerschmitt Bf 109G-4s of Jagdgeschwader 53 flown by aces Oberleutnant Julius Meimberg (with 31 victories at this point) and Feldwebel Erich Paczia (16 victories), flew up to intercept the B-17s on their return flight, as Meimberg would describe decades later in his memoirs, Contact with the Enemy: Memories 1939-1945, “I first came across a departing formation of around 12 Boeings in a very tight formation without fighter protection. This was the opportunity to once again launch a frontal attack. I overtake the group with a wide reach and set off on a collision course in front of them in a curve.” With most of the defensive guns in the rear, they overtook the formation just out of range of the .50 calibers to attack them from the front, the least protected area of the B-17s, before they would peel away and dive for another pass.

However, both Messerschmitts faced withering defensive fire from the formation, with All American’s navigator Harry Nuessle and bombardier Ralph Burbridge manning the nose-mounted guns in their compartment, while flight engineer/top turret gunner Joe James fired from just behind the cockpit, and with the Flaming Mayme’s forward crew responding in kind. Meimberg recalls further, “Now I can no longer pay attention to anything or anyone except the lead bomber. The aiming point of my reflex sight is exactly in the middle above his bow glass, and as we fly toward each other at almost the speed of sound, I lower the deadly red dot by millimeters. A burst of fire from all weapons eats into the enemy’s torso, a red-hot explosion, a short pull on the control stick and I’m above the formation and being thrown around wildly by its propeller gusts. There! A hit! A quick look through the cabin. Was something hit? At the bottom left of the oxygen line, there is an angry, hissing, small flame – I have to get out.”

As he swerved away from the two bombers, Meimberg’s oxygen tanks were hit and caught fire, forcing him to bail out with severe burns. Though Meimberg would survive this day, his burns forced him to be sent back to Germany to recover, and he did not return to flight duty until August 1943.

In the other Bf 109, Paczia lined up on the All American. His machine guns and cannons blazed away at the All American, but the bomber’s crew responded in kind. Just as Paczia begins to roll away to line up for another attack on the bomber, he is incapacitated by the defensive fire formation, either killed outright or severely wounded to the point at which he can no longer control his aircraft. Bragg and Engel rammed the nose down to attempt to avoid a collision as the 109 screamed overhead just inches away from the cockpit before one of its wings sliced through the tail of All American while the rest of the aircraft tumbled to the desert sands below.

[wbn_ads_google_four]

Aboard All American, everyone heard a big “whoomph” and felt the plane shutter and dive. Bragg recalled that it felt like “a slight thud from a coughing engine.” As soon as they were able to collect themselves, all members of the crew immediately had their parachutes ready to deploy. At this moment, Burbridge thought, “Boy, this is it.” Bragg and Engel then had to fight with hands and knees to keep the plane steady and prevent it from pitching up. By throttling back on the engines, however, they were able to keep the plane relatively level. Once the plane was level enough, Bragg rose from his seat to make a quick inspection of the damage to the tail from the top turret before consulting his crew from the radio room, as the intercom systems had been damaged by the collision along with their oxygen and electrical systems.

In a mixture of astonishment and horror, the crew found that the left side of the tail of the plane was completely torn apart, with the entire left horizontal stabilizer missing and the remainder of the tail section, with tail gunner Staff Sergeant Sam Sarpoulus still inside, was swaying in the slipstream. He later said that it felt like riding the end of a kite. Yet remarkably, the right side of the tail held on by just a few remaining spars and metal skin, and there were just enough of the control cables remaining to steer the rudder and the remaining elevator. They were also able to use the analog autopilot system on the Norden bombsight to help keep themselves steady and adjust their heading.

The tail was sturdy enough, contrary to later retellings, for Sarpoulus to crawl to the waist gunners station while carrying his parachute, four gun brushes, and a jacket lent by Bragg. Bragg happened to arrive at the waist section just as Sarpoulus was crawling from the tail turret. With a very sheepish smile, he motioned with his chin to the jacket he was holding and said, “You forgot this, Skipper.” Sarpoulus recalled later that after making it to the waist section, he left behind four gas masks in the tail section, but decided against crawling back for them saying, “I looked at them a minute and thought the hell with them.” One of the crew members was heard over the intercom repeating the comment, “You could drive a jeep through that hole.”

With Biskra 90 minutes flight time away, and with no serious injuries among the crew, Bragg informed the crew that if they felt safer bailing out, they were free to do so, but everyone decided to stick it out, especially since they were still over German lines. With Bragg back in the pilot’s seat, he and Engel had to keep the yokes firmly in their hands and knees to keep the All American flying as straight as possible, while also reducing power to stabilize the aircraft. Some of the remainder of the formation would also slow their speed around the All American to ensure that it did not straggle behind the formation within range of German fighters while the rest headed back to Biskra. Inside the B-17 “Flying Flit Gun,” tail number 41-24412, navigator Lieutenant Charles “Cliff” Cutforth raised his camera up to the sight before him and took the iconic photograph that has kept this story alive for so long. Once they were clear of any German fighters, the rest of the formation flew ahead to land at Biskra before the All-American, with Bragg and Engel keeping the plane steady. Before landing, the crew fired three flares from the aircraft over the airfield to signal that it would be coming in for an emergency landing. The option to bail out over the field was raised once again by Bragg, and once again, every crew member chose to stay.

Now that all other B-17s had landed, the field was cleared, the ambulances were on standby, and the crews who had already landed were watching from the ground in nervous anticipation as the All-American came in to land. Bragg and Engel carefully lowered the main landing gear and flaps to test the responsiveness of the airplane, and fortunately, it responded well. The tail wheel, however, was made inoperative by the collision, so the battered tail of the aircraft would have to take the force of the landing, as well, as they came in on a long and slow approach. Remarkably, the tail held together as it was dragged across the sandy runway, and all onboard the All American walked away to set foot on terra firma. When the ambulances arrived after the engines were switched off, Bragg calmly reported, “No business, Doc.” From then on, Sam Sarpoulus was known among the crew as “Lonesome Sam.”

Before the mission, Bragg and his crew were in need of a replacement ball turret gunner. Elton Conda of the 341st Bomb Squadron stepped forward, sneeringly asking Bragg, “Can you fly the damned plane?” … to which Bragg replied, “Sure, can you shoot the damned guns?” Now back on terra firma, Conda walked up to Bragg. No words were exchanged, but Conda gave Bragg a long, firm handshake before walking away. The rest of the 97th Bomb Group gazed with wonder at the plane that looked as though it should not have been able to fly. Rather than being reduced to a smear on the desert landscape, it was sitting on the ground with its crew still alive to recount the tale, even carrying pieces of the Messerschmitt’s wings in the tail.

Three sightseers from another crew went inside the aircraft on the ground to inspect the damage. One of them turned to Sarpouls and asked, “Say, why didn’t she break in two?” Feeling slightly guilty about coming back home, Sarpoulus was about to respond when the tail broke in two on the ground under the weight of the three men.

One B-17 that never returned from that mission was the lead aircraft, 41-24477 “Flaming Mayme.” As it turned out, among the prisoners of war released from German custody at the end of the war in Europe were three men who had been aboard the Flaming Mayme on that fateful day: bombardier Alfred Blair, navigator Ralph Birk, and tail gunner Robert Knight. All other members of the crew, including Major Robert Coulter, were killed in action. In a letter written in 1988, Blair, who still had 31 fragments of 20mm shells in his right leg and foot when an exploding shell struck the bombsight, recounted that the Flaming Mayme was cut in two by a collision with the same Bf 109 that struck the All American, after which Blair, Birk, and Knight managed to bail out but were captured by the Germans just shy of the Allied lines shortly after touching down. Having been held in separate crews for the remainder of the war, the three surviving members of the Flaming Mayme’s crew agreed through their shared testimonies that their B-17 was lost to a midair collision with the same 109 that hit the All American. This does conflict, however, with Ken Bragg’s account of what happened. He acknowledged that he saw the Flaming Mayme go down, which was flying ahead and to the left of the All American, but that it was shot down by the first of the two 109s (which was likely Meimberg’s plane), which swerved away while the second 109 was hit by returning fire from All American before the collision.

Meanwhile, Julius Meimberg, the surviving German pilot who attacked Flaming Mayme and All American, claimed to have shot down a B-17 before being forced to bail out of his flaming Messerschmitt, but does not claim to have collided with any B-17. It may be possible that perhaps Meimberg did indeed shoot down the Flaming Mayme as Paczia collided with the All American after being incapacitated by defensive fire; or that Meimberg scored some hits on the Flaming Mayme but Paczia collided with both B-17s. Instead of more sources that could provide definitive answers, this aspect of the All American’s story remains clouded by the fog of war.

In August of 1943 an armament officer from the 340th BS, Jerry P. Hall, was informed of the existence of some B-17 wreckage in the desert after the squadron had moved to Oudna, Tunisia. When he and two of his men came to the site to see if they could salvage any useful equipment, they discovered that it was the remains of Flaming Mayme along with the graves of some of the crew buried nearby. Their story, however, seems to be missing in most accounts of the All American’s story, but to tell All American’s story is to tell of the Flaming Mayme, lest we forget.

The crew of the All American soon became the talk of the 12th Air Force, and the photo taken by Cutforth made the news back home. The photo also served as the inspiration for the 414th Bomb Squadron’s new patch, as well as the patch for the modern iteration of the squadron in the US Air Force, the 414th Expeditionary Reconnaissance Squadron, and partly served to inspire the hit song “Comin’ In on a Wing and a Prayer,” though the stories of other heavily damaged B-17s coming home against the odds have also been put forward as inspirations for the popular song.

Perhaps one of the most surprising details that most retellings of this story fail to mention is that the All American flew again after this ordeal. After its return to Biskra, the All American sat at the edge of the airfield, where the men of the 50th Air Service Squadron went to work to return the aircraft to the skies. They removed the battered tail section from All American and replaced it with one from another B-17 in the salvage yard while keeping the original vertical stabilizer and serial number 41-24406. After six weeks of hard work in the desert sun, All American was airworthy once again.

By that point the All American was reassigned to the 353rd Bomb Squadron, 301st Bomb Group at Saint-Donat Airfield near Tadjenanet, Algeria. Crew chief Virgil “Hock” Annala of the 301st reflected on the All American’s time in the group this way: “For all intents and purposes, the marriage of the forward section and the new after section made her look like a B-17. The flight characteristics were something else … her service with the 301st in a combat role was short lived. She was extremely slow and plagued with problems.” It seems that much of this stemmed from the rivet work done to attach the new tail section onto the forward section of All American in the field. After a single combat mission to Borizzo Airfield in Sicily on May 10, 1943, the All American was stripped of all armament and armor and reassigned for non-combat duties such as utility, weather-reconnaissance, and in-theater training, but was largely used to carry troops and cargo.

Following the Allied landings in Italy, numerous airfields were established around Foggia on the southeast corner of the Italian peninsula. All American would carry troops and freight to wherever they were needed and was later assigned to the headquarters of the 15th Air Force Service Command at Bari. But on January 19, 1945, according to USAAF overseas accident reports, the All American was damaged in a taxiing accident when it struck a parked Douglas C-47A Skytrain, serial number 42-100955 of the 62nd Troop Carrier Group, at Gioia del Colle Airfield. By March 6, the All American had been condemned to the salvage yard and was officially stricken from the inventory on April 13.

Much has been said about that fateful day in the skies above North Africa, but the story of the All American and her crew are heroic enough, without any need for embellishment or exaggeration.

The crew on the All American:

-1st Lieutenant Kendrick “Ken” Bragg (pilot)

-1st Lieutenant Godfrey Engel Jr. (copilot) (sometimes confused with Lt. Melville Guy Boyd Jr. of the 100th Bomb Group due to Engel’s signature)

-1st Lieutenant Ralph Burbridge (bombardier)

-1st Lieutenant Harry Nuessle (navigator)

-Technical Sergeant Paul Galloway (radio operator)

-Technical Sergeant Joe James (flight engineer/top turret gunner)

-Sergeant Elton Conda (ball-turret gunner) (Conda was actually part of the 341st Bomb Squadron and was filling in for Bragg’s regular ball-turret gunner who had fallen ill back at base)

-Sergeant Michael Zuk (waist gunner)

-Staff Sergeant Sam Sarpolus (tail gunner)

with special mention to ground crew chief Hank Hyland.

The crew of the Flaming Mayme:

-Major Robert Coulter (aircraft commander, CO of the 340th BS, KIA)

-Lieutenant Jesse Wikle (co-pilot, aircraft’s regularly assigned commander, KIA)

-Lieutenant Alfred Blair (bombardier, POW, WIA)

-Lieutenant Ralph Birk (navigator, POW)

-Technical Sergeant Edward Smith (flight engineer/top turret gunner, KIA)

-Staff Sergeant Svend J.W. Hansen (radio operator, KIA)

-Staff Sergeant Charles Nease (ball turret, KIA)

-Staff Sergeant Claude Hooks (waist gunner, KIA)

-Staff Sergeant James P. Fitzgerald (waist gunner, KIA)

-Sergeant Robert Knight (tail gunner, POW)

Major thanks to all those who assisted behind the scenes in the research behind this article, and for such publications as Pride of Seattle: The Story of the First 300 B-17Fs, by Steve Birdsall, the Collier’s magazine article No Business, Doc, published on April 14, 1943, the podcast Warbirds-Tales from Above for their episode published on February 9, 2021 (Warbirds – Tales From Above: “All American” (libsyn.com)), and Vintage Aviation News’ very own WWII B-17 “All American” Separating Facts from Fiction, The Real Story of WWII’s B-17 “All American“, published June 27, 2013. Without their dedication, this article would not be possible.

[wbn_ads_google_video]

This is amazing, my father was in the 8th Air Force and I have a lot of his training material but few pictures,

that’s cool thank you for your service

I’d like to offer a small correction regarding the 1938 Duke football team. The nickname “Blue Devils” dates to the early 1920’s. The 1938 team, being undefeated and unscored upon in the regular season, was given the nickname “Iron Dukes.” Thanks for the great article!

Thanks! My Dad was a professor at Duke at that time. I was surprised to see the pilot was

from Duke.

No it should be the REDDEVELS