On January 12, 1935, famed aviator Amelia Earhart landed at Oakland Municipal Airport in Oakland, California, after an 18-hour flight from Wheeler Field, Oahu, Territory of Hawaii, becoming the first pilot, male or female, to fly nonstop and solo from Hawaii to the United States mainland. While this flight is somewhat less remembered than her solo flight across the Atlantic or her disappearance in attempting to circumnavigate the globe, Earhart’s Hawaii-California flight remains an important milestone in the history of aviation. She had risen to fame for being the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean between May 20-21, 1932, four years after she had been the first woman to fly across the Atlantic as a passenger in 1928 (though she was already a licensed pilot during the earlier flight). Though several military and civilian aircraft had completed nonstop flights from the US mainland in California to Hawaii as early as 1927, Earhart was determined to be the first to fly solo from Hawaii to the US mainland. For the meantime, however, she would keep her plans secret.

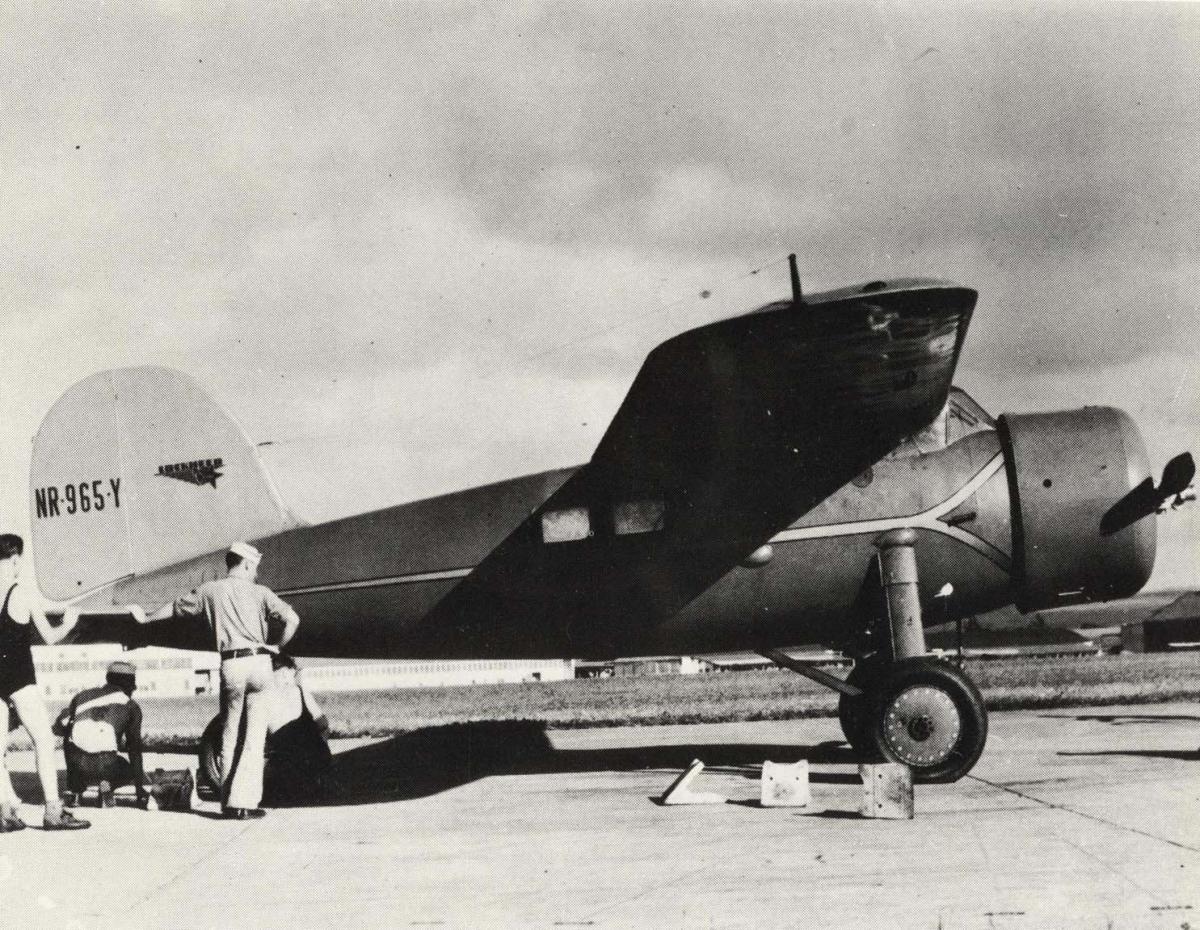

The aircraft in which Earhart would fly across the Pacific from Hawaii to California was a Lockheed Vega 5C, which was an improved model of the Vega 5B she had flown on her transatlantic solo flight, which she had donated to the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia (and which is currently part of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum). This new Vega of hers was built in 1931 at the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation’’s factory in Burbank, California, as construction number 171, registration number NX965Y, on the orders of John Henry Mears, a Broadway producer who also set two circumnavigational speed records in 1913 (using steamships, yachts, and trains) and in 1928 by air. After a third attempt in 1930 in an earlier Vega named City of New York had ended in failure, Mears commissioned the construction of NX965Y as the new City of New York but later abandoned this attempt as well.

In 1931, City of New York was then sold to aviator Elinor Smith, who renamed the aircraft Mrs. Question Mark (painted as Mrs.?). Smith hoped to fly the aircraft, now re-registered as NR965Y, on a nonstop solo transatlantic attempt, but she never completed that goal either. It was then that the aircraft came to be acquired by Amelia Earhart.

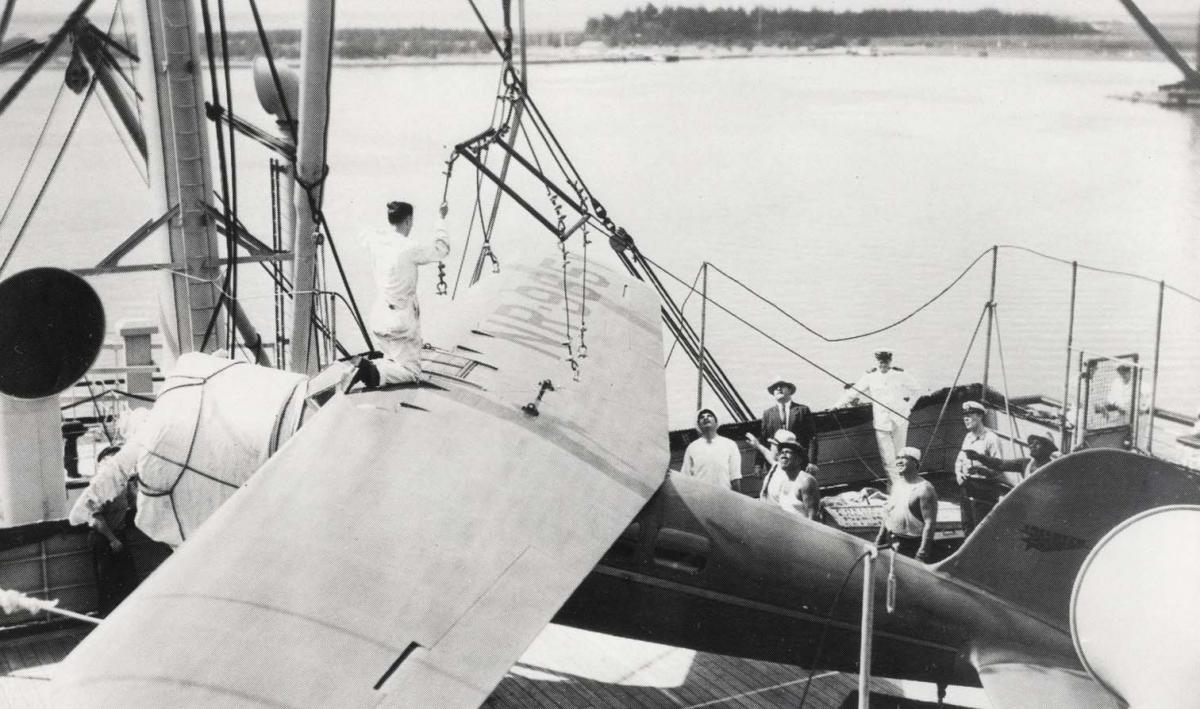

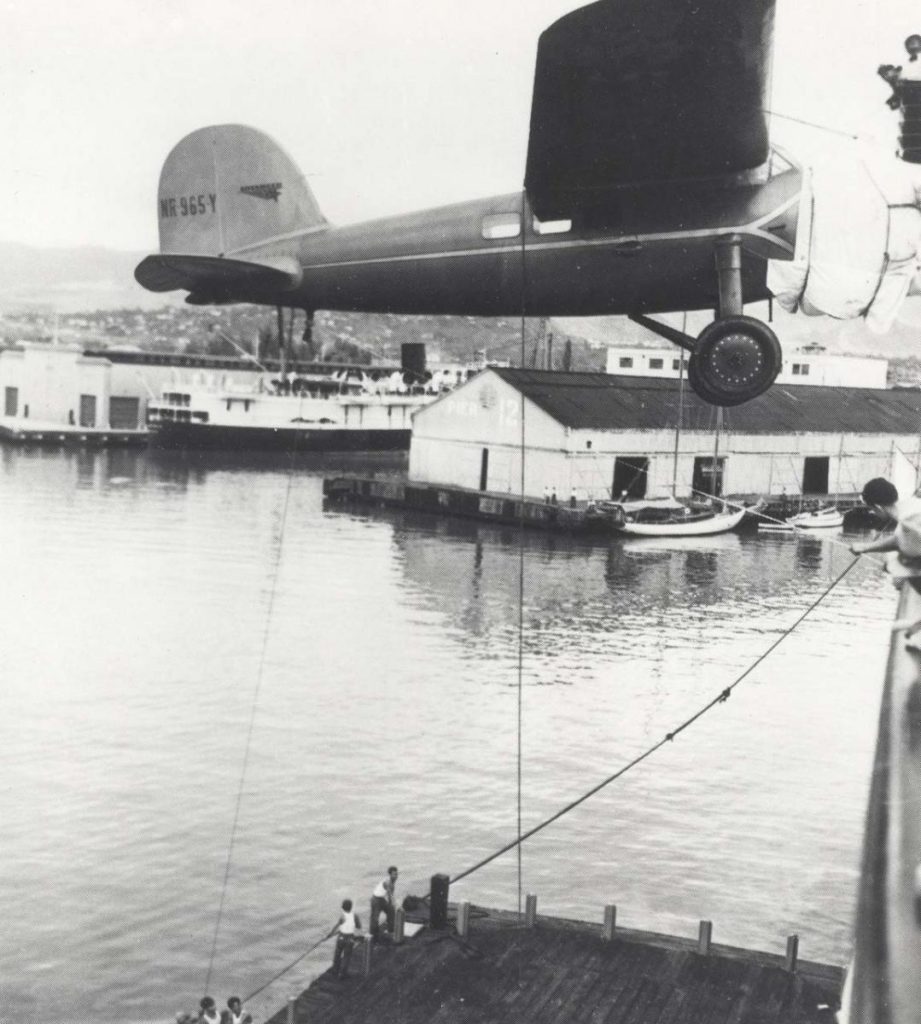

On December 22, 1934, Earhart, her husband George Putnam, and her Vega, along with movie stunt pilot Paul Mantz who served as Earhart’s technical adviser, and mechanic Ernie Tissot, set out from Los Angeles by sea aboard the ocean liner SS Lurline. During the five-day voyage, the Vega was strapped in one piece to the Lurline’s aft tennis court and the Pratt & Whitney Wasp radial engine was run up several times to ensure it did not ingest too much saltwater moisture, and the ship’s radio operator helped with testing the Vega’s onboard two-way radio. Earhart and her entourage would celebrate Christmas at sea aboard the Lurline, which arrived in Honolulu on December 27, with the airplane being barged to the Army/Navy airfield on Ford Island, inside Pearl Harbor. Despite rumors of Earhart’s attempt to fly back from Hawaii, Earhart refused to confirm or deny that she had that in mind, and instead announced that she was on vacation, and that the airplane was for them to fly between the islands.

During her stay, Earhart toured the islands, met with local dignitaries—including Olympic swimmer and surfing pioneer Duke Kahanamoku—and delivered a speech to the University of Hawaii. In the meantime, Paul Mantz had flown the Vega from Ford Island to Wheeler Field, just north of Pearl Harbor, where the first nonstop flight to Hawaii from the mainland US in the Army Air Corps’ Fokker C-2 Bird of Paradise had terminated back in 1927. As the arrival of the new year was celebrated, Army mechanics and technicians assisted Mantz and Tissot in preparing the Vega for a long-distance flight, with Mantz making further test flights while Earhart, already a celebrity, remained the guest of honor at various functions.

There was some controversy, however, as to Earhart’s motivations for the flight. Speculative press suggested the flight would be merely a publicity stunt for Hawaiian business interests such as the sugar plantations and criticized her for having Army mechanics service her plane rather than civilian mechanics at John Rodgers Field (now Daniel K. Inouye International Airport). The Navy, meanwhile, felt that her radios had insufficient range to receive and transmit messages over the ocean. Such was the concern over these and other matters that on January 7, 1935, Earhart was summoned to an emergency meeting at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel in Honolulu, where her sponsors asked her to abandon her transoceanic flight and return by sea with her airplane. According to Hawaii Aviation, Earhart was furious, saying “I have no idea where the rumors of my political influence started … My business is flying. I have spent nearly half of the sum you promised me to get my plane in condition and bring it here, but I can soon recoup that loss. Gentlemen, there is an aroma of cowardice in the air. You know as well as I do that the rumor is trash, but if you can be intimidated, it might as well be true. Whether you live in fear or defend your integrity is your decision. I have made mine. I intend to fly to California within this next week, with or without your support.” Earhart left the boardroom, and the sponsors would continue their support.

On January 11, 1935, Earhart and her plane were ready for the flight, but the weather was not. Local rain showers had muddied the grass field at Wheeler, and the flight was delayed until it was dry enough for the heavily loaded airplane to take off. At 4:45pm local time, Earhart gunned down the 6,000-foot field, carrying 500 gallons of fuel onboard. The Wasp engine roared as mud sloshed under the wheels of the crimson red Vega. Earhart described the takeoff in an article she wrote for National Geographic thusly: “The plane did exactly as expected. The tail came up as it gathered speed, throwing up a cataract of red-brown mud. It grew lighter, as the 550 harnessed horses of the Wasp motor gobbled gas. Then a final bounce and it took to the air, holding it easily as I slowly turned to the right toward Honolulu and Diamond Head. The take-off, I am told, was accomplished well within 3,000 feet—less than half the length of the field.” After passing Diamond Point, all land soon disappeared, not only with the growing distance but from the advance of night as well. Earhart flew much of the flight from 8,000 feet above the waves that night.

“The night I found over the Pacific was a night of stars,” she would recall. “They seemed to rise from the sea and hang outside my cockpit window, near enough to touch, until hours later they slipped away into the dawn.” Earhart kept in contact with the two-way radio communication, spotting the steamship Malolo, a sister ship of the Lurline, steaming 900 miles from Honolulu. She also received radio guidance from commercial radio stations KGU in Honolulu, KPO in San Francisco, and KFI of Los Angeles, with Earhart’s callsign being KHABQ. Just as Paul Mantz had proven during a prior test flight in NR965Y, Earhart could also receive signals as far as Kingman, Arizona while over the vast expanse of the Pacific. In recalling the sunrise during her flight, Earhart wrote, “Crossing the Atlantic, I saw no actual sunrise, because of clouds. This time, with more than half of the Pacific stretched behind me, the rising sun ushered in a new day in orderly fashion. Since I was coming from “down under,” the sun flared over the horizon not straight ahead but somewhat to my right, fortunately for my eyes. Flying full into the glare at high altitudes is very trying, even with dark glasses.”

About 18 hours after leaving Wheeler Field on Oahu, Earhart made landfall at Pillar Point, just 21 miles south from her destination of Oakland Airport. In the same National Geographic article, Earhart wrote, “Pulling up over a notch in the hills, directly on my course, I beheld San Francisco Bay before me. Over San Mateo I sailed and six minutes later NR-965-Y and I sat down on the runway of Oakland Airport, approximately 18 hours from Honolulu.”

The flight had taken 18 hours and 15 minutes, and Amelia Earhart had been welcomed by crowds of 10,000 well-wishers, a marked contrast to the reception of her transatlantic solo flight in 1932 when she landed in a field near the village of Culmore, Northern Ireland, to the bemusement of three farmhands who scarcely believed she had flown from Newfoundland.

After this historic flight, Earhart used NR965Y to become the first woman to fly nonstop and solo from Los Angeles to Mexico City, then from Mexico City to Newark, New Jersey later that year. By 1936, she had sold the Vega 5C to Paul Mantz, who had it featured as a prop in several Hollywood films such Wings in the Dark (1935) and Border Flight (1936). The aircraft then changed hands several times and its registration changed yet again, this time to NC965Y. It was as NC965Y, which was adorned with the name Record Breaker that the aircraft was destroyed in a hangar fire in Memphis, Tennessee on August 20, 1943.

While Earhart’s legacy in the annals of aviation history remains undisputed, it is quite remarkable that 90 years later, the journey taken by Earhart in a small, single-engine wooden airplane is now an everyday occurrence in sleek, pressurized jet airliners, taking countless people from Hawaii to California, with few of them having no idea of the challenges and wonders of that flight back in 1935.

Today in Aviation History is a series highlighting the achievements, innovations, and milestones that have shaped the skies. All the previous anniversaries are available HERE