Before January 3, 1944, Pappy Boyington had been a draftsman and engineer at Boeing before he earned his wings as a Marine Corps aviator in 1937, seeing fleet service out of San Diego and later serving as a flight instructor out of NAS Pensacola until 1941, when he resigned from the Marines to join the 1st American Volunteer Group (AVG), which became better known as the “Flying Tigers”. After flying combat missions against the Japanese over China and Burma in Curtiss P-40s, where he claimed six aerial victories but was officially credited by the AVG with 4.5 kills (two air-to-air kills, one ground kill and shared credit for a ground kill), Boyington returned to the United States and reentered the Marines, being promoted to the rank of major. After serving as the executive officer of Marine Fighter Squadron 122 (VM-122) on Guadalcanal, and the commanding officer of Marine Fighter Squadron 112 (VMF-112), Boyington was made commanding officer of Marine Fighter Squadron 214 (VMF-214) in September 1943. Originally nicknamed “Gramps” by the young pilots under his command who were often ten years younger than him, the 31-year-old was immortalized as “Pappy” Boyington. His men initially nicknamed themselves as “Boyington’s Bastards” but after the Marine Corps public information offices suggested a new name that would be appropriate for civilian newspapers back home, the squadron renamed themselves the “Black Sheep”.

Under Pappy’s guidance, the Black Sheep Squadron became prolific at shooting down Japanese aircraft in the Solomon Islands, flying out of Vella Lavella. Though Boyington had come into disciplinary trouble before the war and while flying with the Flying Tigers, his courage was without dispute, and he earned the admiration his men not only for his leadership that netted him and his men victory after victory, but also for the fact that he would often select the aircraft in the worst shape of the squadron so that none of his men would worry about their aircraft. By January 3, 1944, he was one of the leading US Marine Corps aces of the war, alongside Robert M. Hanson and Joe Foss, but VMF-214 was due to complete its combat tour, and thus Boyington sought to undertake one more combat mission.

That morning, Boyington took off from Torokina Airfield on Bougainville at 6:30am local time, flying F4U-1A Bureau Number 17915, fuselage code 915. A total of 46 Corsairs and F6F Hellcats were to go on a fighter sweep over Rabaul. While en route, some of the fighters, including three Corsairs from VMF-214, aborted the missions on account of mechanical failures. Upon their arrival over the target area at around 8:00am, the remaining American fighters encountered two large formations of Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters, most probably from the 253 and 204 Kōkūtais (Naval Air Groups).

In the ensuing dogfight, Boyington claimed to have downed a Zero, which was confirmed by other American airmen. Then, Pappy’s wingman, Captain George M. Ashmun, piloting Corsair BuNo 20723, was overwhelmed from all sides by attacking Zeros and was shot down. To this day, Captain Ashmun’s remains have never been recovered. With his wingman down, Boyington now found himself being surrounded. During the onslaught, a 20mm cannon shell exploded in the bottom of his Corsair, wounding him in the leg, head, ear and forearm. Boyington leveled off in his crippled Corsair over the St Georges Channel between New Britain and New Ireland, flying on for another half mile until his fuel tank caught fire, forcing Pappy Boyington to bail out at 100 feet, his parachute opening just before he hit the water at around 8:45am. In the chaos of the action, Boyington was seen to have been hit, but was not seen to have survived. Later, the remaining American fighters made their withdraw, with the Japanese fighters soon coming in to land themselves. Boyington remained in the water for eight hours until a submarine surfaced near him. At first, he hoped it would be a US submarine, but to his dismay, it was a Japanese one, the I-181, which took him to Rabaul.

For the next 20 months, Boyington endured 20 months of brutal imprisonment that involved regular beatings contracting malaria, and his combat wounds being left to fester. The Japanese never publicly announced that they had captured him, so during that time, he was classified as missing in action, presumed dead. In February 1944, Boyington and five other captured American aviators on Rabaul were selected to be flown to Japan for further interrogation. They were flown in a Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bomber from Rabaul to Truk Atoll, right in the middle of the American air assault known as Operation Hailstone. After surviving the airstrike, Boyington and the prisoners were then flown further on to Saipan, then Iwo Jima, and finally to Yokohama, Japan, where he would be held in Ōfuna Camp from March 1944 to April 1945, when he was transferred to the Ōmori camp in Tokyo Bay. While being held as a POW, Boyington met Olympic runner Louis Zamperini and submarine commander Richard O’Kane.

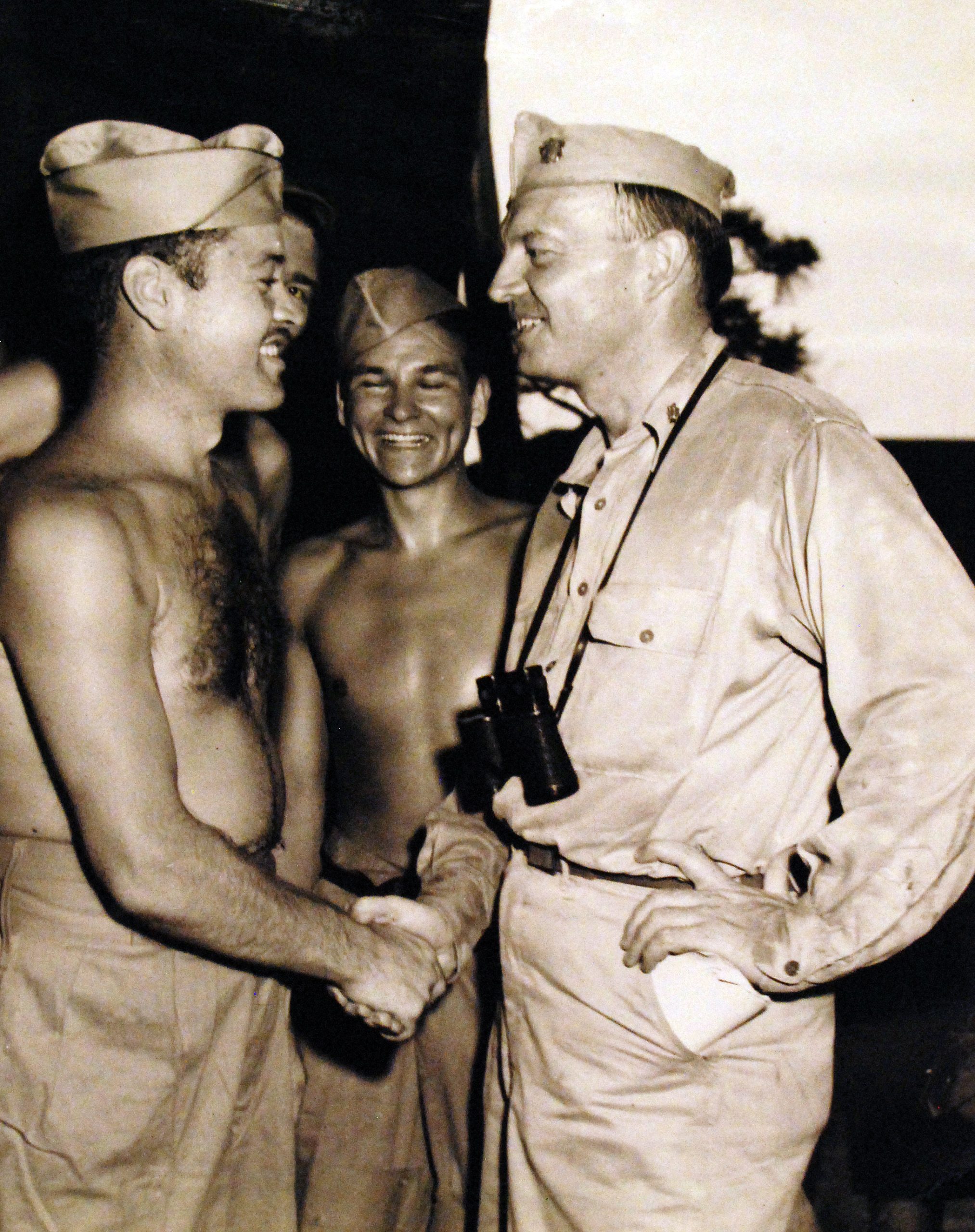

When Japan finally surrendered on August 15, 1945, the US Army Air Force and US Navy organized aerial supply drops to POW camps in Japan to help feed the starved POWs until they could be released from captivity. During one of these flights, a photograph taken at low altitude revealed a sign on one of the barracks roofs that read “PAPPY BOYINGTON HERE!” To the men of the Black Sheep Squadron, it seemed as though Pappy had come back from the grave and was given a hero’s welcome by the surviving members of VMF-214 when he arrived in Hawaii on September 12, 1945. Back in the States, Boyington’s citation for the Medal of Honor had been signed in March 1944 by the late President Franklin Roosevelt. After being flown into Washington, D.C., Boyington was presented the Navy Cross by the Commandant of the Marine Corps, General Alexander Vandegrift, on October 4, 1945. The following day, he was presented with the Medal of Honor by President Harry Truman at a White House ceremony.

After the war, Gregory Boyington retired from the Marines as a Colonel in 1947, but his struggles with alcoholism would continue long after the war. In 1958, Boyington wrote a best-selling autobiography, Baa Baa Black Sheep, which led to the 1970s TV drama of the same name, which was very loosely based on Boyington’s memoirs. Though the number of victories he scored has been disputed, the United States Marine Corps History Division biography of Colonel Boyington states that he was “credited with the destruction of 28 Japanese aircraft,” though others have stated he scored a total of 22 confirmed aerial victories. “Pappy” Boyington died of lung cancer on January 11, 1988, at the age of 75, and was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

Today in Aviation History is a series highlighting the achievements, innovations, and milestones that have shaped the skies. All the previous anniversaries are available HERE

In his later years he was a very kind and humble man. I met him working as a senior in high school flying computer parts in 1976 from Lewiston to Hayden Lake, ID. He ran a fixed base operation and introduced himself as ‘Greg.’ I’d been studying WWII air war on my own and knew about Pappy Boyington, The Flying Tigers, The Eagle Squadron, Joe Foss and several Army fighter pilots like Bob Hoover, Gabby Gabreski, Chuck Yeager, Bud Anderson, and others. One day Greg asked me to ride my motorcycle from Lewiston to Hayden Lake airport at a certain time. He’s told me where to park and to walk into the operations building. If anybody asked to tell them Greg said to park there. I did and arrived just in time. We went to the flight line and a P-51 buzzed us, wheeled around and taxied to us, spun around and parked next to us. The airport was having an airshow. The cockpit canopy was already slid back, so out popped Bob Hoover where Greg told him to stop showing off, shut up and he wanted him to meet someone. That was me. I felt so honored, a nobody high school kid that a Mustang pilot was being introduced to. I knew Bob Hoover from the history books and thanked Greg immensely for introducing me. We all walked to Greg’s operations building with the local TV news following us. Greg bought me a Coke. It was amazing talking to Bob Hoover. Greg never let on that he was Greg Boyington, i.e., Pappy Boyington, top Marine Ace in the Pacific Theater. He was just my flying buddy, Greg. It was years later when I was working as an engineer and read his obituary that I realized Greg, one of my favorite high school mentors, was one of my idols, top WWII Marine Ace, Medal of Honor winner, Pappy Boyington. What a great American.

He’s a great man of courage!

I love everything about Him!

I have some ww2 pic I would like to know more about

Thank you for sharing that.

Col Boyington’s was the first “adult” book I read, I was 9 or 10 years old.

Ive never forgotten a line from the book, “Show me a hero and I’ll show you a bum”