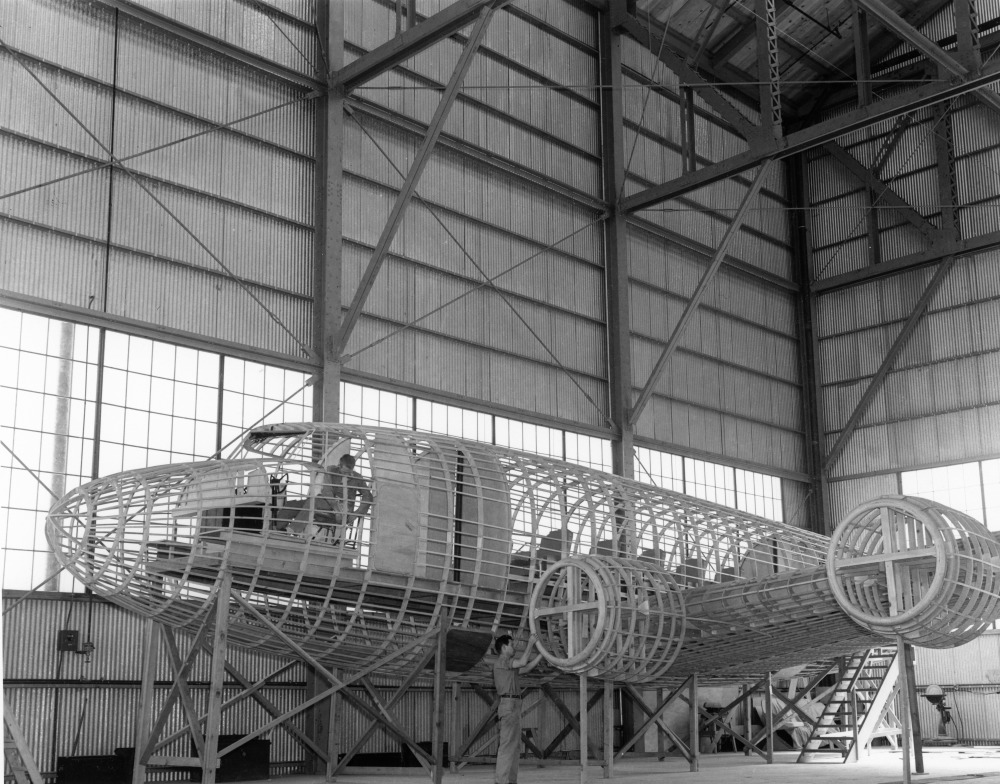

In 1939, Howard Hughes, who was among many things the largest shareholder of Transcontinental & Western Air (TWA), invited Jack Frye (president of TWA), engineer Clarence “Kelly” Johnson and Robert E. Gross, president of Lockheed Aircraft Corporation, to a private meeting at Hughes’ residence in Hancock Park, Los Angeles. At the meeting, they discussed what Hughes called the “airliner of the future”. At the time, Lockheed was developing a new airliner called the Model 44 Excalibur, which had originally been designed as a twin-tail aircraft but reworked to a three-tail design and was to be powered by four Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp radial engines, have a tricycle landing gear configuration, and carry 32 passengers and two crew. They were even building a wooden mockup at their plant in Burbank. However, Hughes wanted even better carrying capacity, a cruising speed of 300 mph, and a range of 3,600 miles, meaning it could span the entire continental United States nonstop. These demands would eventually lead to the cancellation of the Model 44 Excalibur, while the basic outline of the design was readapted into the Model 049, which was temporarily called the Excalibur-A, but would be renamed the Constellation.

For its time, the Constellation was one of the most innovative airplanes in the world. Its wings were derived from those of the P-38, which was being developed by Lockheed and featured hydraulically boosted controls and a deicing system on the leading edges of the wings and tail. The tail was the most distinctive part of the Connie’s design. Because most contemporary hangars were not high enough to accommodate the Constellation if it had a single tail, three vertical stabilizers were fitted to provide sufficient longitudinal control while being able to access pre-existing hangars at airports around the country.

The Constellation was to be powered by a quartet of Wright R-3350 Duplex-Cyclone radials, with the Pratt & Whitney R-2800 as a potential backup. But at $450,000, the Model 049 was also the most expensive airliner design up to that point, but Hughes provided the necessary funding through the Hughes Tooling Company, through which Hughes ordered 40 aircraft. Lastly, Hughes and TWA had Lockheed keep the project under wraps so that TWA’s main rival, Pan American Airways, would not be able to purchase any Constellations before TWA had built up its own fleet.

Development of the Constellation carried on steadily until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, after which development of the P-38 and PV-1 Ventura patrol bomber took precedence. Meanwhile, the USAAF took over the production order for the Model 049 and designated the type as the C-69.

It was under these circumstances that the first of the “Connies”, construction number 049-1961, made its first flight on January 9, 1943, flying from Burbank Airport, over the San Gabriel Mountains to Muroc Army Airfield (now Edwards AFB) in the Mojave Desert. At the controls in the left seat was Boeing’s Chief Test Pilot, Eddie Allen, with Lockheed’s Chief Test Pilot, Milo G. Burcham, as copilot. Joining them was Lockheed’s chief research engineer and the Constellation’s designer, Clarence L. “Kelly” Johnson, along with Johnson’s assistant, Rudy Thoren, acting as flight engineer, and chief mechanic Dick Stanton. At the time, the aircraft was painted in military colors, but since it had yet to be formally accepted by the USAAF, the civil registration NX25600 was present on the aircraft. After practicing takeoffs and landings, they returned to Burbank, with a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and a Lockheed Model 18 Lodestar as photo chase planes off their wings. Upon landing, Allen commented, “This machine works so well that you don’t need me anymore!” And thus, NX25600, which was later accepted into the Army Air Force on July 28, 1943, as USAAF #43-10309.

A total of 22 C-69s were built for the USAAF, and with the demand for other transports such as the Douglas C-47 Skytrain, the Constellations were kept stateside during the war, with the majority of the C-69s being converted immediately after the war as pressurized airliners for TWA and later other airlines, having proved during the war through flights undertaken by Howard Hughes and Jack Frye themselves that the aircraft could fly comfortably across the United States nonstop, and later variants such as the L-749 Constellation were able to fly the transatlantic routes from the US to Europe nonstop, leading to Transcontinental & Western Air rebranding as Trans World Airlines, and becoming the biggest competitor against Juan Trippe’s Pan American Airways.

But the story of the very first Constellation was far from over. During the war, XC-69 #43-10309 was retained by Lockheed for further testing. At one point, it was modified with Pratt & Whitney R-2800s, becoming the XC-69E. With the war having ended, Lockheed sold the XC-69E, now registered as NX67900, to Howard Hughes for $20,000, who brought it to Hughes Airport in Culver City, where the H-4 Hercules flying boat (aka the “Spruce Goose”) had been built. In May 1950, Lockheed purchased the aircraft back from Hughes for $100,000, by which point the aircraft had only 404 hours logged.

N67900 was then modified by Lockheed to serve as the prototype for the Lockheed L-1049, which would become known as the “Super Constellation”. The aircraft was cut into three sections and lengthened by 18 feet with the addition of two new sections (one forward of the front wing spar, the other aft of the rear spar), the fuselage, wings, and landing gear were strengthened, and the height of the three vertical stabilizers 2.5 inches (6.35 centimeters) for greater longitudinal stability, and the cabin could now accommodate between 76–94 passengers and crew compared to the L-749A’s 47–63 occupants.

On October 13, 1950, the Super Constellation prototype, now registered as NX6700 and powered by four R-3350s, took off from Burbank Airport on its first flight with Lockheed test pilot Tony LeVier at the controls. Following the introduction of the Super Constellation to the world’s airlines, the US military took delivery of some of these aircraft for use as transports, with the US Air Force receiving the C-121, and the Navy the R7O/R7V, but by 1952, both the Air Force and the Navy were interested in making the Constellation into an airborne early-warning radar system. This would see the old Constellation prototype undergo one last conversion, becoming an aerodynamic test aircraft for the U.S. Navy PO-1W radar early warning aircraft (later redesignated WV-1 and EC-121 Warning Star), with the aircraft being nicknamed the Beast of Burbank. It was even used to test the Allison YT56 turboprop engine by placing it in the #4 position. Finally, in 1958, the first Constellation was purchased as a source of spare parts by California Airmotive Corporation and was dismantled and later scrapped.

The Constellation family of aircraft would remain in use as one of the last piston-engine airliners before the jet airliners took over commercial aviation, while the miliary models served in both war and peace before retiring by 1982, being among the last piston engine transports in military service. Today, numerous Constellations, Super Constellations, and even the later L-1649 Starliners have been preserved in air museums around the world, with a couple examples having been restored to airworthiness in the United States and Australia. Even if the Connie can no longer be seen at airport terminals today, their legacy is beyond dispute, but among the first airliners to be pressurized, allowing planes to fly higher, further, and faster in greater comfort than ever experienced before, and among aviation enthusiasts, its distinctive three tails make it one of the most recognizable aircraft in aviation history.

Today in Aviation History is a series highlighting the achievements, innovations, and milestones that have shaped the skies. All the previous anniversaries are available HERE