We have just received the July/August, 2022 report from Chuck Cravens concerning the restoration of the Dakota Territory Air Museum’s P-47D Thunderbolt 42-27609 at AirCorps Aviation in Bemidji, Minnesota. We thought our readers would be very interested to see how the project has progressed since our last article on this important project. So without further ado, here it goes!

Update

This month, work centered on getting the cowling completed, installing the cockpit enclosure, skinning the fuselage undersides, and installing duct covers.

Cockpit Enclosure

The characteristic razorback cockpit enclosure has been installed on the P-47. It really adds to the finished look of what will soon become the only Republic-built P-47 razorback flying.

Engine

Aaron installed the prop governor this month.

Landing Gear

One important project this month involved filling the reservoirs for the main landing gear oleo struts. Oleo struts are a kind of fluid-spring shock absorber filled with gas (nitrogen in this case) and hydraulic fluid.

Fuselage

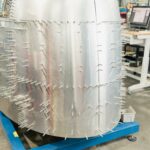

Cowling

A P-47 Thunderbolt’s engine cowling is replete with complex curves and presents a significant fabrication challenge. Mike has spent months carefully replicating this assembly.

Wings

Ammunition bay doors, hinge fairings, and wing root fairings were all part of the restoration workload this month.

Toughness

The P-47’s legendary toughness is mentioned frequently in discussions about the type’s combat record. According to WWII aviation lore: ‘If you want to impress the girl back home, fly a P-51… but if you ever want to see her again, fly a P-47.’ Like many sayings of that era, this one is perhaps a little excessive, but there is no doubt that the P-47 has a well-deserved reputation for ruggedness. It could both dish out and take a formidable amount of damage.

According to the Smithsonian Air & Space museum: “Of the 15,683 P-47s built, about two-thirds reached overseas commands. A total of 5,222 were lost – 1,723 in accidents not related to combat. The Jug flew more than half a million missions and dropped more than 132 thousand tons of bombs. Thunderbolts were lost at the exceptionally low rate of 0.7 percent per mission and Jug pilots achieved an aerial kill ratio of 4.6:1. In the European Theater, P-47 pilots destroyed more than 7,000 enemy aircraft, more than half of them in air-to-air combat. They destroyed the remainder on very dangerous ground attack missions.”

In fact, the Thunderbolt was probably the best ground-attack aircraft fielded by the United States. From D-Day, the invasion of Europe launched on June 8, 1944, until VE day on May 7, 1945, pilots flying the Thunderbolt destroyed the following enemy equipment:

86,000 railway cars

9,000 locomotives

6,000 armored fighting vehicles

68,000 trucks1

Many pilots would stick with a damaged aircraft and crash-land, instead of bailing out -such was the strength of the airframe.

1 Smithsonian Air& Space Museum, website: Accessed 8-4-2022

There were several reasons for the excellent survivability results of belly landing in a P-47. One was that, unlike the P-51, there was no scoop on the underside of a Thunderbolt. The P-51’s scoop could dig into the ground and flip or stop the airframe very quickly, making an injury or fatality to the pilot more likely.

In a water landing, the Mustang’s scoop could catch water and flip the plane.

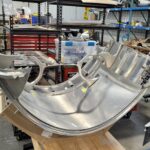

The smoothly curved belly of a P-47 was much more likely to slide over the ground or water in a safer, more controlled fashion.

An internal design factor also helped make belly landing safer in a P-47. In the fuselage lower section is a crash skid designed to support and protect the underside of the airframe. It is mounted to the very strong forged crossties that connect each wing to the other.

The crash skid worked in conjunction with the underside ducts to cushion the impact of a belly landing.

2 American Air Museum in Britain website: accessed August 9,2022

Perhaps most importantly, The P-47 was larger than any other single-engine fighter, so there was more structure and mass protecting the pilot in a crash situation.

This mass and strong structure was a factor in the P-47’s ability to absorb battle damage as well as crash damage.

The air-cooled radial engine famously could run with significant damage and wasn’t vulnerable to cooling system damage as liquid-cooled inline engines were.

However, the common description of the Thunderbolt as a flying tank is a little extreme. A tank is heavily armored. Calling the P-47 a tank implies that it carried more armor than other fighters. The armor plate installed in US fighters in WWII was pretty much limited to a plate behind the pilot, and sometimes a smaller one just in front of the cockpit. Almost all had bulletproof glass in front of the pilot, either in the windshield itself as P-51s and later P-47s had, or a separate glass plate inside the cockpit enclosure as the razorback P-47s used.

The drawings clearly show that there is little difference in the amount of actual armor plate protecting the pilot in a P-51 or a P-47.

And that’s all for this month. We wish to thank AirCorps Aviation, Chuck Cravens for making this report possible! We look forwards to bringing more restoration reports on progress with this rare machine in the coming months. Be safe, and be well