By Adam Estes

Whenever someone mentions “Vought” and/or “Corsair” in aviation circles, most enthusiasts think immediately of the F4U Corsair that helped secure U.S. naval air supremacy in the skies of the Pacific during World War II, provided multirole capabilities in Korea, and even endured as one of the last piston-engine fighters in active service, serving in well into the 1970s in Central America. A few hardcore enthusiasts may think back to the A-7 Corsair II attack aircraft that served in the skies over Vietnam in 1970s and Kuwait and Iraq during Operation Desert Storm two decades later, and remained in operational service until the last examples were retired from the Hellenic Air Force in 2014.

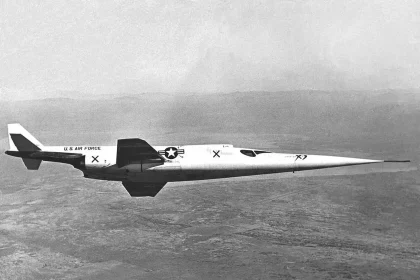

Very few, however, will think of the O2U and O3U observation biplanes of the late 1920s and early 1930s, for it was these Vought aircraft to bear the name Corsair. Developed for the United States Navy as a ship-based observation aircraft, these original Corsairs would serve in the Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard from shore bases and the aircraft carriers USS Lexington (CV-2) and USS Saratoga (CV-3) with fixed landing gear and from catapults on battleships and battlecruisers with floats and pontoons. In the latter role, they were regarded as the “Eyes of the Fleet”. The last examples these aircraft were retired from service in 1941.

Both variants were fitted with Pratt & Whitney radial engines, the most ubiquitous of which being the reliable R-1340 Wasp and were armed with both forward-firing synchronized machine guns in the nose, a defensive gun for the rear observer, and bomb racks on the lower set of wings. While many of the O2Us and O3Us went through their service lives without firing a shot or dropping a bomb in anger, however, in Nicaragua in 1928, Marine aviator Christian Frank Schilt flew his O2U into heavy small-arms fire to evacuate wounded Marines, for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor. The Corsair, much like its descendants in the Vought family tree, was widely exported, sporting the roundels of Argentina, Brazil, China, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Peru, and Thailand. Some of these export models would also see combat during the Chinese Civil War (1927-1949) and the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), the Colombia-Peru War (1932-1933), and the Franco-Thai War (1940-1941).

Today, there are just two original Corsairs left in the world, both of which are export models. A V-93S is displayed at the Royal Thai Air Force Museum in Bangkok, Thailand, and the uncovered fuselage of a V-65F exists in the Museo de la Aviación Naval Argentina in Bahía Blanca, Argentina. In addition, a replica of a Chinese Corsair can be found in the Beijing Air and Space Museum. However, no original examples of the O2U or O3U were preserved in the United States, but Grand Prairie, Texas a dedicated group of volunteers at the Vought Heritage Foundation recently completed a reproduction of an O3U-3 Corsair.

The Vought Heritage Foundation (VHF) has restored several Vought aircraft, including an RF-8 Crusader, the last surviving F6U Pirate, the company’s first jet aircraft, and the unique V-173 “Flying Pancake”. The foundation also constructed a full-scale reproduction of Vought’s first naval aircraft, the VE-7 “Bluebird”, and assisted in the restoration of an F7U Cutlass for the USS Midway Museum, with many of the other aircraft being displayed either at the Frontiers of Flight Museum at Dallas’ Love Field or the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida.

The O3U-3 project traces its origins back to a 1/16 scale model that had been started from scratch by scale modeler George E. Lee in late 1988. Lee, whose skill in the scratch model-building community was unmatched, chose to display his Corsair with the markings of Bureau Number 9156, the 10th aircraft of Observation Squadron 1 (VO-1), which was assigned to the battleship USS Pennsylvania (BB-38) in 1936. A friend of Lee’s who had served in the Navy had managed to save a portion of fabric from the original aircraft, and it was that artifact that inspired Lee to recreate 9156, which was further helped by his acquisition of original Vought drawings.

However, Lee would not live to complete the project as he passed away on May 31, 1992. Before his death however, Lee bestowed the project to fellow modeler John Alcorn, who began work on the O3U after he completed his own de Havilland DH.9A model, which won the award for “Best Aircraft” at the 1998 IPMS/USA convention in Santa Clara, California. When the model was completed in 2000, it, along with the original fabric, was displayed at the IMPS/USA Convention held that year in Dallas, after which they were donated to the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida. It was at the convention where VHF’s Archive Director Dick Atkins and senior member Teddy Trept saw the model and suggested that at some point, the foundation should build a full-scale reproduction of the O3U-3. In mid-2008, Atkins presented this idea to the management and craftsmen of the VHF and got approval to move forward with the project.

Before a single rivet could be installed or a single weld made, the team needed detailed drawings of the aircraft’s structure, and that required searching through VHF’s vast collection of drawings. Volunteer archivist Bill Spidle took on the task and when his search, which took over 2,000 hours, was completed he’d gathered over 1,600 drawings from the VHF microfilm reel library, along with obtaining an additional 30 assembly drawings from the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C. These microfilm scans of the drawings came with some issues, however. Many of the drawings were fourth or fifth generation reproductions of the original 1930s-era drawings, and the text and dimensions of these reproductions were barely legible. Fortunately, though, another VHF member, Adam Galan, used computer programs such as Photoshop and PhotoScape X to make the text, dimensions, and drawing details readable, after which Carl Klaprott and Dave Morse produced full-scale drawings for the fabrication process.

Like many aircraft of its day, the O3U Corsair was of tubular steel construction for the fuselage and tail stabilizers and the wings were made of wood, and all covered in fabric. On the reproduction, solid wing components such as the spars were made using Sitka fir in place of the original Sitka spruce, with the leading edges and the ribs were made with birch plywood, all bonded with waterproof wood glue and coated with epoxy varnish.

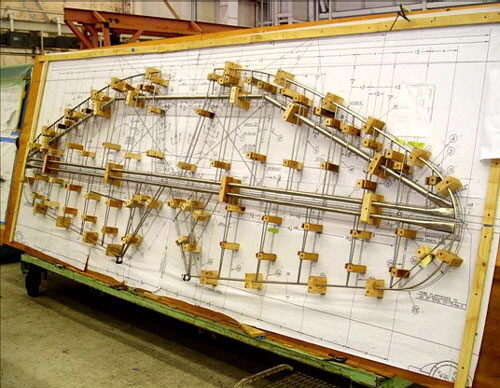

The wings are divided into five sections; left and right lower wings, left and right lower wings, which are attached to a center section. Once the components were fabricated against the drawings for reference, they were held in place for the adhesive agents to set. Once the internal wing structure was complete, the team focused on building the welded tubular steel framework of the fuselage.

Work on the fuselage’s steel truss framework would see the top members and connecting trusses being fabricated first. The diagonal and vertical were aligned and welded together, and eventually, the upper and lower portions were welded in place, followed by the attachment brackets for the wings, center-line pontoon, engine, fuel tanks, and controls. The tandem cockpit arrangement of the O3U featured dual controls for the pilot and the observer. On the reproduction, Dillon Smith led the team in charge of fabricating the cockpit and the controls. One of the team members, Richard Sheaner, reproduced the throttle quadrant from Vought drawings, complete with the levers for the engine throttle, mixture control, and spark advance control. However, only the front cockpit was equipped with the mixture and spark advance controls. The twin 68-gallon fuel tanks, which were situated on both sides of the cockpit, were constructed of steel skins that were warmed and wrapped around a wooden mold, with angles riveted to the internal ribs before the angles were then welded. This part of the project was completed by Stan Bullard.

Fitting an airworthy R-1340 engine on a static reproduction was of course deemed too expensive a project, so Dick Atkins worked with Covington Aircraft of Okmulgee, Oklahoma to obtain non-airworthy parts that volunteer Jack Brouse and Bill Condon, could use to assemble a pristine and externally correct R-1340, which was completed in 2010. Fitted to the front of the engine was a period-correct Hamilton Standard propeller, with red, yellow, and blue tips, supplied by an aircraft supply store in Beaumont, Texas.

Bill Condon also fabricated the engine cowling by fabricating a mold to cover 180° of the cowling before constructing a wood shell covered with plaster to achieve the desired shape. Condon followed this by sanding and filing the plaster, then sealing it and coating it in a release agent. While the original engine cowling was made of aluminum sheets rounded and shaped into place, the decision was made by the team to construct the reproduction cowling from fabric, which would require less work than the metal, but would still have the desired look. Condon would achieve this look by covering the cowling mold with several layers of fabric coated in epoxy resin, creating one 180° part, which was then reproduced and spliced together to create a singular piece. After the two halves were brought together, the cowling was sanded, trimmed, and primed in order to receive its final paint scheme.

The challenges faced by the VHF team were not limited to the construction of the aircraft itself, but also a home for the project. From 2014 the project was shut down for 18 months as the VHF was forced to move due to local development of the former Ling-Temco-Vought (LTV) facilities in Dallas into new commercial properties. In May 2018, the VHF had to endure another nine-month shutdown when those same facilities were demolished. Finally, in 2019, the team secured a lease for a building from the Grand Prairie Independent School District to complete the final stages of the project. Shortly thereafter the project was shut down again because of the pandemic.

In spite of the facility changes, and the tight quarters of the new spot, the project continued, and on April 11, 2024, volunteer Rusty Branum announced that the project had been completed. The Corsair, resplendent in the same VO-1 markings as the 1/16th scale model that inspired the project, now rests on a cradle for its center float.

With the Corsair now complete inside the workshop, the question now is to determine its disposition. The goal of the VHF has always been to have the reproduction on display to the public, just like their previous restoration projects. One leading contender for a potential home for the O3U-3 is the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, but VHF has yet to make an official decision.

From the initial vision back in 2008 to the completion in 2024, a total of around 60 volunteers have contributed to the completion of the O3U-3 Corsair, which took approximately 80,000 hours to build from start to finish.The author would like to thank the Vought Heritage Foundation for their involvement in the creation of this article and for their efforts in reviving the Vought O3U Corsair.

Boy it would look great on the back end of a battleship.

I am elated to learn about the Vought Heritage Foundation and your successful achievement in bringing back a significant part of the largely forgotten Interwar Navy Period of the 1930s. I think she should reside at the Uvar Hazy Air Museum near Washington D.C. where more people can see and admire it. At the risk of sounding a little greedy, with the success of this build, it would be considerably easier to build perhaps a second and third. Best of luck to you all and a hearty congratulations for your magnificent contribution to American History.