By James Church

The restoration of one of the most famous of the surviving Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses, The Swoose, continues with the National Museum of the United States Air Force (NMUSAF) in Dayton, Ohio. Built as B-17D USAAC Serial No. 40-3097, none of those present at the time it emerged from the production line in Seattle, Washington could have imagined what lay ahead for it, nor the place in history it would eventually cement itself in. That it managed to have survived at all is a miracle unto itself. The oldest surviving B-17, and the only D model in existence, its service record has ensured its place in the pantheon of historic aircraft preservation.

Initially assigned to the 19th Bombardment Group (BG), based at March Field, California, in April 1941, it would not soon gain the name Ole Betsy. The following month, it participated in the first mass aircraft flight from the U.S. mainland to Hawaii. The U.S. was now on a war-footing, anticipating a conflict with Japan, and steps were being taken to protect its many Pacific assets further. That September, it then took part in the longest mass flight from Hawaii to the Philippines. It was here where the Fortress and its crews would go on to distinguish themselves against vastly overwhelming odds in what would soon become an untenable and hopeless situation.

When the anticipated conflict materialized, it was swift and brutal. The attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, saw much devastation and loss of life, while further attacks across the Pacific were equally devastating for the forces stationed in these areas that were insufficiently prepared and provisioned for their eventuality. Though ill-equipped, the U.S. and local forces fought bravely, in a vain attempt to halt the inevitable defeat. The Philippines were squarely in the crosshairs of Imperial Japan, and suffered terribly. The U.S. forces there had only partially been supplemented with men and material to bolster its defenses at the time of the Japanese attack there, and it was a losing battle from day one, regardless of the bravery shown, and the willingness to fight back. Without support, it was soon apparent that it had become a lost cause.

But the Philippines did not give up without a fight, and our subject aircraft was in the thick of it. Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor took place, on December 7th, Ole Betsy took part in the first U.S. combat mission in the Philippines. Over the following three weeks, it would go on to fly several missions against the Japanese Forces while based there. With the situation worsening by the day, the decision was made to evacuate the aircraft and crews to Java, where they continued operations. On one mission, which took place on January 11, 1942, Ole Betsy suffered severe damage while engaged in a thirty-five-minute long-running battle off the coast of Borneo with three Mitsubishi A6M Zeros. Ole Betsy truly lived up to its “Flying Fortress” moniker, as two of the Zeros were downed in the process.

Damage was extensive, however, and this action paid to its days of flying combat missions. A valiant effort was required to return Ole Betsy to the air; however, with air assets in short supply, the effort was deemed necessary, so components from other damaged aircraft were gathered to repair it. An entire new tail section from another damaged B-17D was grafted on, and four new engines were sourced and installed on the now-veteran bomber. Deemed unfit for further combat, it was to be used in the armed transport role, due to the effort put into returning the aircraft to the air using components from several different aircraft, its new pilot, Capt. Weldon Smith dubbed it “The Swoose ‘half swan-half goose!’” based on a popular song.

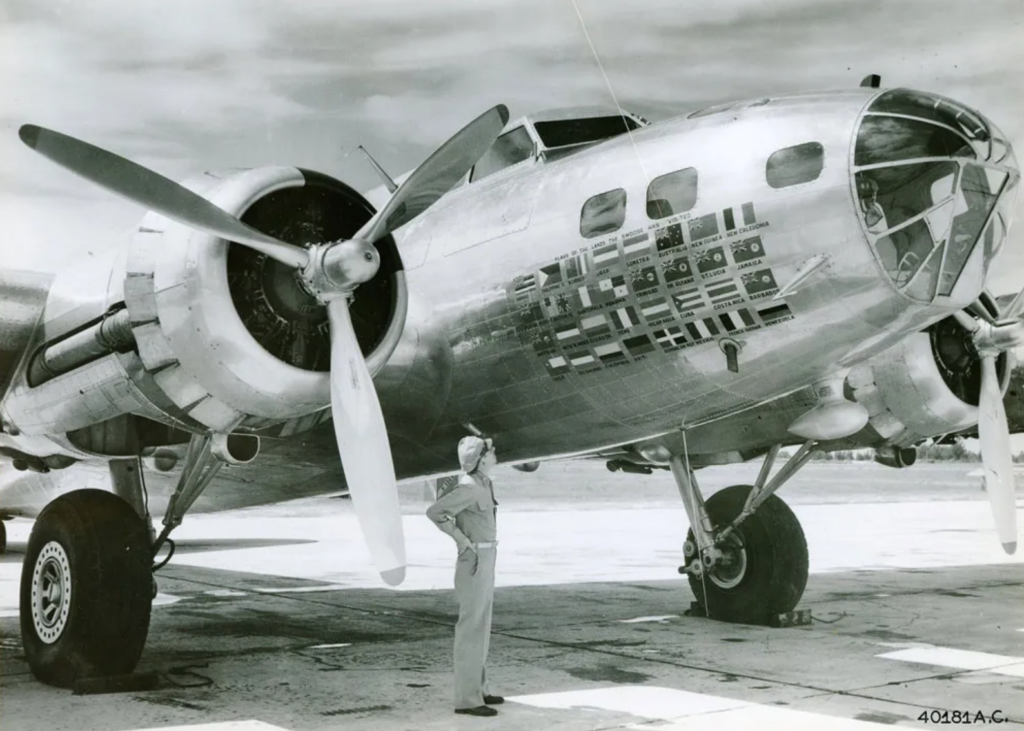

The aircraft eventually became the personal aircraft of Lt. General George Brett. Brett’s pilot was Capt. Frank Kurtz later named his daughter “Swoosie” in fond remembrance of the B-17, and she went on to become a well-known Hollywood actress. When Gen. Brett returned to the U.S. in the summer of 1942, he brought The Swoose with him. Stripped of armament and fully overhauled, which included the fitting of a complete set of wings from a later B-17E, The Swoose would continue in use as Brett’s transport until both he and the aircraft were retired in December 1945. As such, The Swoose gained the added distinction of having been in continuous service from the very beginning to the very end of the war. Having survived its combat duty, this historic aircraft also thankfully escaped the mass-scrapping of redundant combat aircraft following the war. Someone saw the worth of saving it for posterity, and as such, it was gifted to the Smithsonian Institution, which accepted it sometime in the late 1940s. Sadly, it would remain in storage with them for the duration of its tenure in their care, never being displayed to the public. The Swoose would sit at the Silver Hill, Maryland, storage facility of the Smithsonian Institution until 2008, when it was transferred to the NMUSAF for restoration and eventual display in Dayton, Ohio.

NMUSAF spokesman Ken LaRock graciously notified us of work being accomplished on The Swoose to date: “Work continues to be focused on the fuselage. The nose section has been cleaned, and work continues to remove corrosion in that area. Due to corrosion issues in the nose, we had to remove a few skins to remedy that problem. Once all the corrosion has been dealt with, we will finish the necessary repairs and then reinstall the (original) skins. We have also started the cleaning process in the bomb bay. This area is 100% original and untouched since it left service, so we will remove the minor corrosion we have found there. The radio room has been cleaned, and we found some substantial corrosion in that area. Work will commence on correcting that once work in the waist area is finished, which has also been cleaned, and all corrosion has been dealt with. Sheet metal repairs throughout have been ongoing. The tail section of the fuselage has been cleaned, and corrosion has been removed. Sheet metal repairs have been completed, and the structure is being reassembled.”

The following is a statement from the NMUSAF on its stated goals for the restoration of The Swoose and its eventual display: “In considering how best to preserve the aircraft, the NMUSAF is opting to take a combined restoration/conservation approach to bring the aircraft back to life in its transport configuration. The numerous modifications done over the years, the existence of original art and markings, and the components the NMUSAF possesses all point to this configuration being the best choice. By combining restoration and conservation, the NMUSAF intends to preserve as much of the original markings as possible.

Project Description/scope

This is both a restoration and conservation project. Some airframe areas need repair and restoration for structural integrity and exhibit-worthiness, while others will be conserved as-is to maintain originality. The overall aim is to present the artifact in the context in which it was received, i.e., to preserve it in the configuration of its final mission. A combination of restoration and preservation will ensure its longevity, structural and historical integrity, and safe public display in a controlled environment. This means the aircraft’s identity as The Swoose will be maintained with as much original fabric in situ as possible. The minimally invasive preservation approach is one option in the spectrum of possible restoration/preservation/conservation practice, and as in all NMUSAF restoration work, it assures the artifact’s ethical treatment as a museum object.

Project Justification

This project strengthens the NMUSAF’s identity as the premier collection of American combat aircraft and promises to increase visitorship by being the only “straight tail” B-17 on exhibit worldwide. The Swoose’s distinctive shape and its fascinating record of combat, reconfiguration, and transport service round out the Pacific Theater WWII air power story and improve the Museum’s Global Reach interpretation. Preserving the plane as it was received, i.e., as a transport, respects its integrity as an artifact, eliminates very difficult or impossible physical restoration and equipment issues, and helps tell Airmen’s stories with authenticity. Airpower enthusiasts eagerly await its completion, and casual visitors will appreciate its unique story and appearance.”

No B-17s were built in Renton. The Renton site was used to build B-29s during the war. Boeing built B-17s at their plant in Seattle. The B-17D was exclusively built by Boeing. Later models, the B-17F and B-17G, were built by Boeing in Seattle and also Lockheed-Vega in Burbank, California, and Douglas in Long Beach, California.

Thanks George. We just edited the article.

The Smithsonian should have never traded the plane away. The NMUSAF ruined the aircraft after hacking into it to revert it back into its bomber configuration. Now, the aircraft got a restoration it didn’t need. The Smithsonian would have given the aircraft the conservation the aircraft deserved.

They kept all the pieces when they put the bathtub turret in. Most people wanted the restoration make her appear as ol Betsy, but it would have taken too long, and cost too much. I just hope they can make her shine again..and find room for her. I have a lot of former coworkers who are in the restoration hangar, I’ll have to ask.

Kudos to the NMUSAF for its approach. As someone who has spent more than three and a half decades in aircraft restoration I can attest to the difficulty in deciding what to conserve and what to replace. Nobody wants to see George Washington’s axe after the head has been replaced twice and the handle has been replaced three times.