By Adam Estes

As some readers may be aware, the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio has begun the process of transferring one of the most significant B-17s extant to the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum (NASM). The historic, combat-veteran bomber will eventually go on display at NASM’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia. For those unaware of the historical significance of the subject of this article, it is certainly one of the most incredible stories of an individual B-17 Flying Fortress, one which certainly earns the term odyssey to describe its journey.

B-17 expert Scott Thompson in one of his recent updates wrote “The B-17G previously displayed at the NMUSAF in Dayton, B-17G 42-32076, better known as Shoo Shoo Baby, has been slowly moving to the National Air and Space Museum as part of trade many years ago (the NMUSAF got the Swoose). It did see the fuselage and inner wing sections at the NMUSAF restoration packed up and ready for transport. Rumor at the museum is that the NASM is coming very soon to get it. Eventually, the B-17G will be reassembled and placed on display at the NASM, most likely at the Udvar-Hazy Center at Dulles.”

The story of the Shoo Shoo Baby begins like many other B-17s, at Boeing Plant No.2 in Seattle, Washington, where it was built as construction number 7190. Accepted into the US Army Air Force as serial 42-32076 on January 17, 1944, it was subsequently fitted with all necessary armaments and other combat-related equipment at the Continental Airlines Modification Center #13 at Denver Municipal Airport, which became Stapleton International airport following WWII (currently no longer existing as an airport), and the United Air Lines Modification Center #10 at Cheyenne Municipal Airport (currently Cheyenne Regional Airport). After being processed at Grand Island Army Airfield, Nebraska, its last stop in the US before going to England was Presque Isle Army Airfield, Maine. Arriving at RAF Burtonwood, Lancashire on March 2, it would ultimately be assigned to the 401st Bomb Squadron of the 91st Bomb Group, 8th Air Force at RAF Bassingbourn on March 23. The aircraft’s allotted code was LL*E, and the crew named the aircraft Shoo Shoo Baby, after a popular song by the Andrews Sisters that was the favorite of crew chief T/Sgt Hank Cordes and his wife back home. The nose art, inspired by Alberto Vargas’ Hawaii pin up girl for Esquire, was applied by line mechanic Cpl. Tony Starcer, one of four nose artists in the 91st. Just one day after arriving, Shoo Shoo Baby flew on the first of what turned out to be 23 missions during its operational life with the 91st. Unlike other B-17s in the group, 42-32076 did not have a permanently-assigned crew, but Lt. Paul G. McDuffee, who ferried the aircraft from Burtonwood to Bassingbourn, would fly the ship on several occasions.

One of the most interesting anecdotes in the Shoo Shoo Baby’s history was when her crew flew her on a one-ship mission for the 91st Bomb Group. On April 9, 1944, the 91st flew up to bomb the port city of Gdynia in occupied Poland. However, the mission was soon called off, but the crew of the Shoo Shoo Baby, under the command of Lt. McDuffee, could not be reached due to a faulty radio. They climbed through heavy clouds to 30,000 feet, encountering a formation of B-24s. Realizing it was clearly the wrong group, they searched but found no sign of the 91st, though they found another formation of B-17s. They followed the formation to a Focke Wulf plant in Marienburg (now Malbork), Poland. They dropped their bombs when the others did, and followed them back to England, then diverted to return to Bassingbourn, where all four engines quit on the runway due to fuel exhaustion. Despite expecting to be chewed-out, they were instead congratulated for having single-handedly given the 91st Bomb Group a victory. When McDuffee completed his tour of duty and was rotated out, an extra “Shoo” was added to the aircraft on May 25. Just four days later, Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby would fly her last mission with the 401st.

Mission #23 was to be another long one. The 401st was to bomb a Focke-Wulf aircraft component factory in Poznań, Poland. On route to the target, while crossing the German border, the No.3 engine lost oil pressure and quit. The pilot in command, 2nd Lt. Robert Guenther, tried to feather the propeller on this engine, but it would not rotate. Instead, the No.3 propeller continued to windmill, and Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby began to lag behind the formation, but stayed on course. Releasing its deadly payload over Poznań, pilots Guenther and 2nd Lt. George Havrisik turned westward. What surprised them most, however, was that the German fighters that responded to the American bombers were focused on the distant formations, but no attention was paid to them despite the fact that they were straggling outside the formation. Though fortunate for the crew aboard Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby, it was uncharacteristic of German fighters that actively looked out for stragglers to make easier kills.

But before they even reached the Baltic coast, the No.2 engine also failed. Realizing they could not return to England, Guenther asked the navigator, 2nd Lt. John M. Lowdermilk, to plot a course for Sweden. The crew knew what this meant: internment by Swedish officials and the confiscation of the aircraft, but it was much more preferable to be interned in Sweden than become prisoners of war in Germany. All loose equipment was ordered to be thrown overboard to lighten the aircraft, including guns and ammo, radio equipment, and spare clothing not in use. The crew even attempted, after ball turret gunner S/Sgt. Nick Premenki exited the turret, to jettison the turret altogether, as was standard procedure in the event of a wheels-up landing, but the turret would not budge. Lowdermilk plotted a course for a coastal town on the southernmost tip of Sweden, Ystad. As they reached the Swedish coast, however, the crew of the Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby encountered flak fired on them from anti-aircraft batteries. It was clear to the crew that the Swedes were trying to warn them not to do anything foolish. Just before reaching land, a third engine went out. It was at this point when a Seversky J 9, an export version of the prewar P-35 design, flew up and escorted the stricken bomber to Malmö, about 58 kilometers northwest of Ystad. There, a B-24 Liberator had just landed ahead of them, and Guenther and Havrisik had to swing the Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby wide to avoid the Liberator on landing.

Upon landing, the crew and the plane were interned by the Swedish government. The Swedes treated Allied pilots fairly, but they were still far from home, and it was the intention of the US State Department to bring home the American airmen. Handling the negotiations in Sweden was American air attaché, Colonel Felix M. Hardison, who had been stationed in Stockholm since February 1944. Hardison had previously served as a B-17 pilot with the 19th Bomb Group of the 5th Air Force, stationed in the South Pacific, flying the famed B-17E 41-2489, known as Suzy-Q, which had returned to the US after extensive combat in the early phases of the Pacific War. Hardison finally struck a deal with the Swedes. In exchange for 300 American airmen being returned to the United States on the guarantee that the airmen would be prohibited from further combat, the nine B-17s were transferred to the Swedish government on July 10. 1945. Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby was among the nine B-17s, and this would turn out to be a boon for the airlines in Sweden.

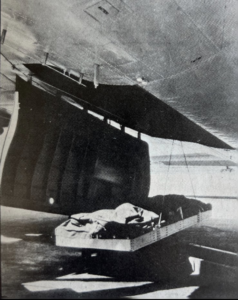

Before the war, they had been interested in acquiring Douglas DC-4 airliners, but when war broke out, the orders dried up as the DC-4 was adapted by the USAAF as the C-54 Skymaster. In addition to this, the Swedes had been flying airliners throughout Europe, usually filled with diplomats trying to negotiate during the war. Though the war was not over, by late 1944, it was clear that sooner or later, the Allies would win, and Sweden would still need long-range airliners for the immediate postwar years for routes that the venerable DC-3 simply didn’t have the range to achieve. And so, after the American airmen were sent on their way home in October 1944, the Swedish government ordered Svenska Aeroplan AktieBolag (Swedish Aeroplane Company Limited (SAAB)), to convert seven of the bombers into airliners while the remaining two examples would be cannibalized for spare parts. All military equipment was removed, the nose section was lengthened by three feet, and interior settings in the former waist gunners and radio operator compartments would provide the aircraft with the ability to carry 14 passengers. In addition to this, the bomb bay was converted to carry cargo, with the left hand bay door sealed shut and reinforced to be part of the floor, while the right hand door would still open so that a lift could be lowered from the bomb bay to bring cargo and luggage up into the compartment. They were also referred to as “Felixes” in honor of the American air attaché.

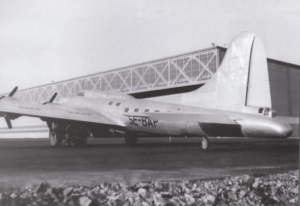

Registered on the Swedish civil registry as SE-BAP for flight testing with Swedish Intercontinental Airlines (Svensk Interkontinental Lufttrafik AB, SILA), which operated through the publicly-backed AB Aerotransport, Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby flew again on November 2, 1945, and was soon sold to Danish Air Lines (Det Danske Luftfartselskab, DDL) and registered as OY-DFA, and was given a new name; Stig (Wanderer) Viking. DDL received another converted B-17G that had landed in Sweden during the war, USAAF serial 42-107067, registered as OY-DFE, which was named Trym (a figure from Norse mythology) Viking. As an airliner, Stig Viking would travel the world, starting out with a Copenhagen-England route, but eventually flying as far as Khartoum, Sudan, Nairobi, Kenya, and Johannesburg, South Africa. With the introduction of the long-awaited DC-4 to the international market, the Swedish-operated Felixes were soon retired, and they were scrapped.

They were not without incident, however, as on November 28, 1945, when Stig Viking was on approach to Blackbushe Airport in Yateley, Hampshire, the left landing gear failed to extend, so the pilot made an emergency landing that resulted in no injuries to any occupants, and the aircraft was soon repaired and returned to service. However, Danish Air Lines’ other B-17 “Felix” was not so lucky. Trym Viking was written off on January 30, 1946, when it overshot the runway on arrival from England to Copenhagen Airport and collided with a parked RAF Douglas Dakota III, serial number KG427. Though no one was seriously hurt, both aircraft were beyond economic repair and were eventually scrapped. Meanwhile, Stig Viking, the former Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby, continued in service with DDL until March 31, 1948, when it was assigned to the Danish Army Air Corps. There, it was assigned the serial 67-672, and would carry yet another name, “Store Bjørn” (Great Bear). During its military use in Denmark, it was converted into an aerial survey aircraft for use in Greenland, with the addition of cameras, mapping radar, and a 1,400-liter fuel tank in the bomb bay. On December 1, 1949, it was transferred to the Royal Danish Navy but continued its work in Greenland, and when the Danish Army Air Corps and Naval Air Service were merged to become the Danish Air Force, Store Bjørn continued its survey work in Greenland, often working alongside US Air Force survey aircraft. It would continue its work in Greenland until October 1, 1953, when it was retired from flight duty and placed in storage.

On February 6, 1955, it was purchased by the Babb Company Inc. of New York, an aircraft brokerage firm. It did not return to the U.S. at that point, however, as the firm sold the old bomber off to the Institut Geographique National in France for continued use as a survey plane, this time over France and her overseas territories and colonies. Registered as F-BGSH, the bomber previously known as Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby would continue to fly for the IGN, being based out of Creil Airport near Paris, along with other B-17s modified for such purposes. One such aircraft was the B-17G 44-85718 (registered as F-BEEC), which later flew for the Lone Star Flight Museum as Thunderbird and is now undergoing maintenance at the Erickson Aircraft Collection in Madras, Oregon on behalf of the Mid America Flight Museum in Mount Pleasant, Texas. Another aircraft flown with the former Shoo Shoo Shoo baby at this time was the B-17G 44-8846, which later flew in the movie Memphis Belle (1990) and is displayed at La Ferte Alais, France as The Pink Lady. F-BGSH surveyed the Middle East, Africa, and South America before being retired from flying for IGN on June 15, 1961. Its engines and other parts were removed, and it was kept on a corner of Creil, receiving damage to its nose section from an accident at one point, but otherwise quietly sitting on display at Creil. Were it not for a chance discovery, Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby was likely destined for the scrapyard.

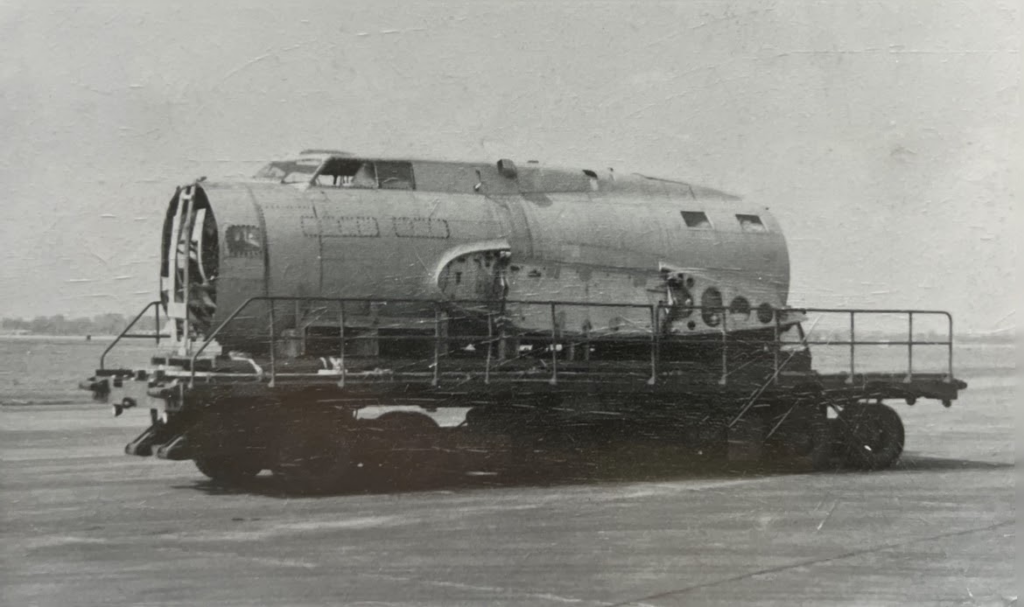

This rediscovery of Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby’s combat record was made by Australian aviation historian Steve Birdsall, who had by this point recently left Vietnam after serving as a war correspondent. He tracked down the service record of 42-32076 and brought the attention of its existence to the 91st Bomb Group Memorial Association and the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. The museum already had a B-17 in its ranks, B-17G 44-83624, but this one had never seen combat, being accepted into the USAAF on April 26, 1945, and serving in the postwar years as a missile launcher (MB-17G) and a drone director (DB-17G) before being donated to the museum in 1957. Needless to say, the chance to snag a combat-veteran B-17 was too good to pass up. The museum appealed to the US and French governments, and on April 22, 1971, the Shoo Shoo Baby was transferred to the NMUSAF. But that was the easy part. There was still the problem of shipping it back to America. This was achieved by dismantling the old aircraft at Creil and trucking it in pieces to Rhein-Main Air Force Base near Frankfurt, West Germany, where it was loaded aboard a Lockheed C-5A Galaxy and flown to Wright-Patterson AFB on June 17, 1972, to be restored by volunteers on the base.

The years had not been kind to Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby. The museum, having only moved to its present-day location from the Patterson Field portion of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base just two years prior and with other aircraft in need of restoration, chose to store Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby for another six years. It was then that the 512th Military Airlift Wing at Dover AFB, Delaware agreed to take on the project in 1978. But rather than simply restoring it to static display condition, Shoo Shoo Baby would be restored to fully flyable condition. The work lasted 10 years, and although the aircraft served in combat in bare aluminum, the sheer amount of work to bring the old Baby back to its wartime configuration would mean that leaving it in bare aluminum would show differences between the old panels of aluminum and the new. This combined with the need for long-term corrosion protection led to the decision, rather than apply a silver lacquer to the aircraft, to apply an olive-drab and neutral gray camouflage that was modeled off a unique variation developed for B-17s manufactured at Boeing plants in Seattle where the olive drab looped around the engine cowlings. The change to olive drab also resulted in the bomb row turning white rather than being a different color after every fifth bomb, the aircraft identification codes turning yellow from black, and where the original block numbers on the nose were all on olive-drab against the natural metal finish, a small portion incorporating the aircraft’s serial and subvariant distinction was left unpainted. In 1981, all completed portions of the aircraft were painted, and since the nose section was among the completed portions, Tony Starcer was called out of retirement to recreate his nose art for the aircraft back in 1944. Unfortunately, Starcer would not live to see the aircraft completed, passing away in 1986, but his recreation of the nose art remains today.

On September 10, 1988, Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby rolled out of the restoration hangar at Dover Air Force Base to a public ceremony celebrating the completion of her restoration. She would return to Dayton, but this time she would fly under her own wings. After several shakedown flights, flying as a US government aircraft with her wartime serial number standing in for an N-number, Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby arrived at Dayton on October 12 for a final ceremony on October 15 with an escort of two P-51 Mustangs, with the landing at 11:00 being accompanied by two Beechcraft T-34 Mentors. Once the public ceremonies were over, Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby was brought into the museum’s hangars, while the museum’s previous B-17G, 44-83624, would go on to be displayed at the Air Mobility Command Museum at Dover AFB under the name “Sleepy Time Gal”. This is the point, until recent years, where the story ended, but as it so happens, it seems the Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby has somewhat of a restless spirit if one were to be poetic.

In 2005, after over 50 years of being on display in the city of Memphis, Tennessee, the B-17F 41-24485 known to history as the Memphis Belle was brought to Dayton for restoration and eventual display. Two years later, in 2007, the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s collections committee voted to transfer the oldest existent B-17, B-17D 40-3097 “The Swoose” to the National Museum of the USAF as well, and The Swoose would arrive the following year in 2008. The latter trade resulted in a deal between the National Museum of the USAF and the National Air and Space Museum that would see the Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby transferred to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum upon completion of either the Memphis Belle or The Swoose. In May 2018, the Belle was completed, and yet another ceremony followed, where a changing of the guard if it were commenced by placing the Memphis Belle and the Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby face to face before the former took the latter’s place and the latter was sent to the storage hangars to be disassembled for the journey to the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center at Dulles International Airport, Chantilly, Virginia. As of this article, the engines and some other components have already arrived at Udvar-Hazy, while the rest of the aircraft, especially the wings and fuselage remain, for the time being, at Dayton. The reason for this delay has been because of the ongoing renovations at the National Mall, which should take another two years to complete.

As we await the complete transfer of the Shoo Shoo Baby to the Smithsonian, we have a story of what it was like to fly overseas on the Shoo Shoo Baby as an airliner.

Related Articles

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.

Amazing, wonderful story. As an old former Navy command pilot of an unarmed SP2H aircraft flying “Market Time” recon flights in Vietnam, the Sea of Japan and other such garden spots. I take great pleasure in reading stories about and honoring extraordinary airmanship and about individual aircraft that have their own spirit that speaks quietly saying: Come find me. I’ve made great flights with fine air crews for our country. I can still shine for you.

As a youth, I remember well the Andrew Sisters singing “Shoo Shoo Baby”. https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=KjrM3E-xSj0

Thanks for sharing this Rick!

Thanks Rick for the link to the song Shoo Shoo Baby by The Andrews Sisters. I can picture the crew of Shoo Shoo Baby huddled around a small radio in a ready room listening to this song.

I saw Shoo Shoo Baby at Dover AFB during her restoration, and was impressed by the dedication of the team to every detail of the job as well as the obvious pride of workmanship that went into the project!

Just a couple of spelling corrections – it was Paul McDuffee, and I’m Steve Birdsall.

Also, the original name “Shoo Shoo Baby” was simply ornate lettering, no nose art. When Tony Starcer painted the Varga girl on the nose he also correctly added an extra “Shoo”.

Thanks Steve, we will correctly immediately!

Steve, Nice to hear from you. I’m Mike Leister the guy who originated the Shoo Shoo Baby restoration at Dover. Later we started the Air Mobility Command Museum at Dover and restored a second B-17G, non-combat vet. We started with virtually no supporting organization and no money, it was a labor of love

Mike, Thanks for the original restoration. I remember reading about the flight to Wright-Patt.

However, it is time to return Shoo, Shoo, Shoo Baby to its original finish, natural aluminum. NASM is in the process of stripping their Bf 109 G to the original wartime camouflage for this particular aircraft.

The same should be done for the Baby. But it won’t, as it is “too big” for the same “return to original wartime” finish treatment.

Not told in this excellent article is that Doc Hospers, founder of the Vintage Flying Museum in Fort Worth Texas, original owner and restorer of “Chuckie” the B-17, flew Shoo Shoo Baby to the museum for its final flight. He was an excellent pilot and a skilled B-17 pilot. Sadly he has since flown west for the last time. Also, Chuckie has a new home and a new name. Chuckie is/was the only PathFinder B-17 in existence (flying) and the new owners seem to have no want to properly restore her.

It was not a B-24 that caused them to go around landing in Sweden. It was my dads B-17 Little John UX-J 97314 92nd BG 327th BS piloted by Lt.Victor Trost.

I have a photo of the Shoo! Shoo Baby nose art taken in England during WW 2 and the nose art is different than shown in this article.

Ref the RAF Dakota KG427, which DDLs other B-17 collided with, carried Royal Canadian

Air Force titles when rammed, so probably belonged to Canada. OY-DFE did not carry the

name “Trym Viking”. Four weeks before the crash DDL had decided to name all their aircraft with “Viking” names, and “Trym” was intended for OY-DFE, but had not yet been

applied to the aircraft.