by Adam Estes

The March Field Air Museum in Riverside, California has numerous restoration projects on the go presently, efforts which range from a multitude of Cessna O-2 Skymasters and Beech T-34 Mentors to an Antonov An-2 “Colt” and of course Starduster, the Boeing B-17G Flying Fortress which served for a period as General Ira Eaker’s command aircraft in the Mediterranean Theatre during WWII.

One aircraft which stands out in the museum’s restoration queue at present, however, is Boeing B-29A Superfortress 44-61669 (on long-term loan from the National Museum of the USAF). For years, the museum believed that this aircraft was actually Flagship 500, a B-29 which flew 11 combat missions against mainland Japan while serving with the 883rd Bombardment Squadron, 500th Bombardment Group, 73rd Bombardment Wing from their base at Isley Field (now Saipan International Airport) on the island of Saipan in the Northern Marianas. But a recent refurbishing effort, coupled with new research, points to the airframe’s hidden history.

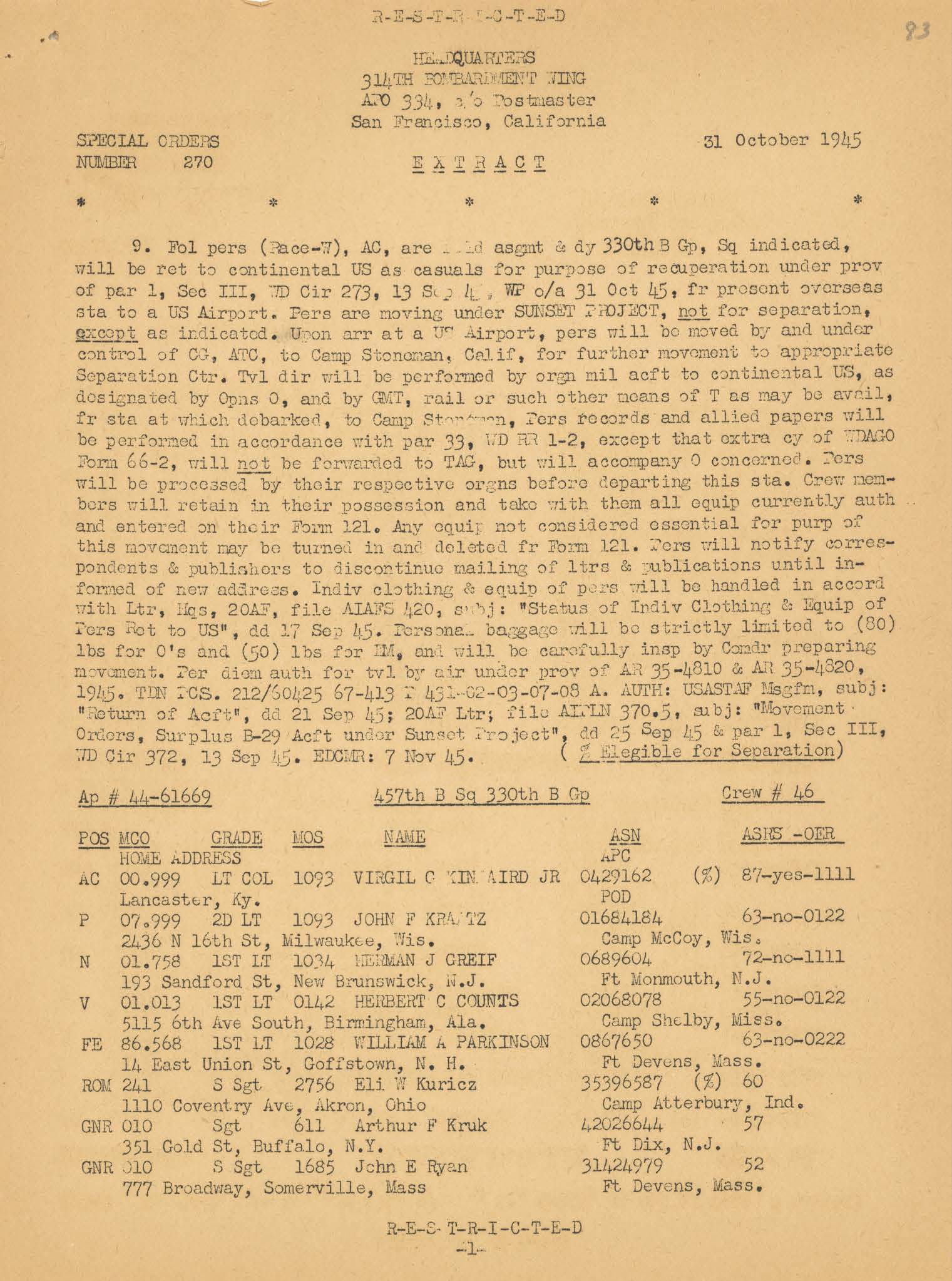

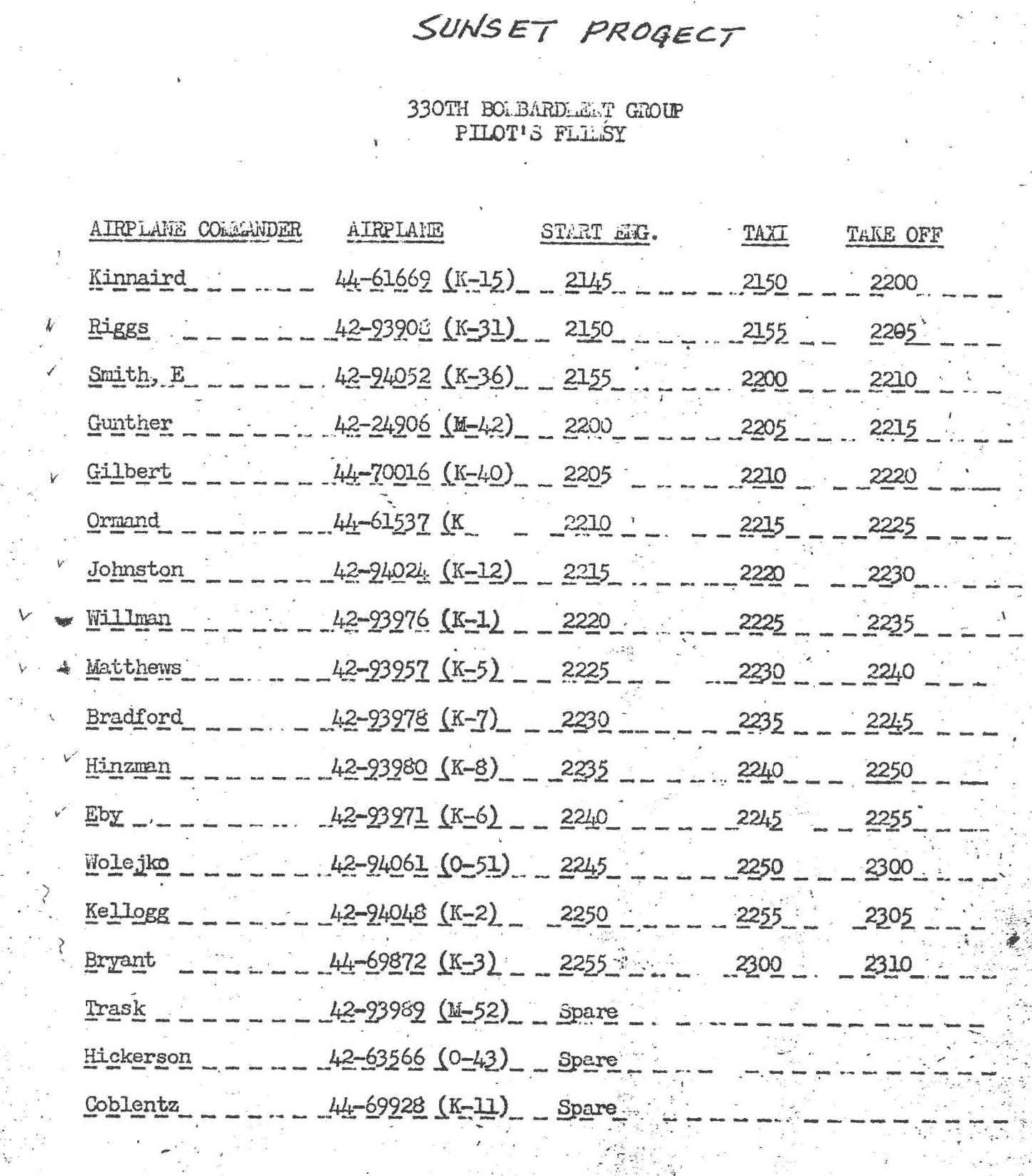

While working on the B-29’s wings a group of the museum’s volunteers discovered vestigial traces of some interesting paintwork on the upper starboard inboard section. When the team outlined these details in tape it revealed the symbols ‘K 15’. This proved perplexing, as no aircraft from the 883rd Bomb Squadron or the 500th Bomb Group ever had such markings applied to them. Wanting to know more, the museum reached out to several archives and discovered, much to their surprise, that 44-61669 had never actually belonged to the 883rd BS, the 500th BG, or even the 73rd BW. Instead, they found that their B-29 had served with the 457th BS, 330th BG, 314th BW at North Field (the present-day Andersen AFB) on the island of Guam during the final days of WWII. This discovery has obviously revealed a significantly different wartime history for the aircraft.

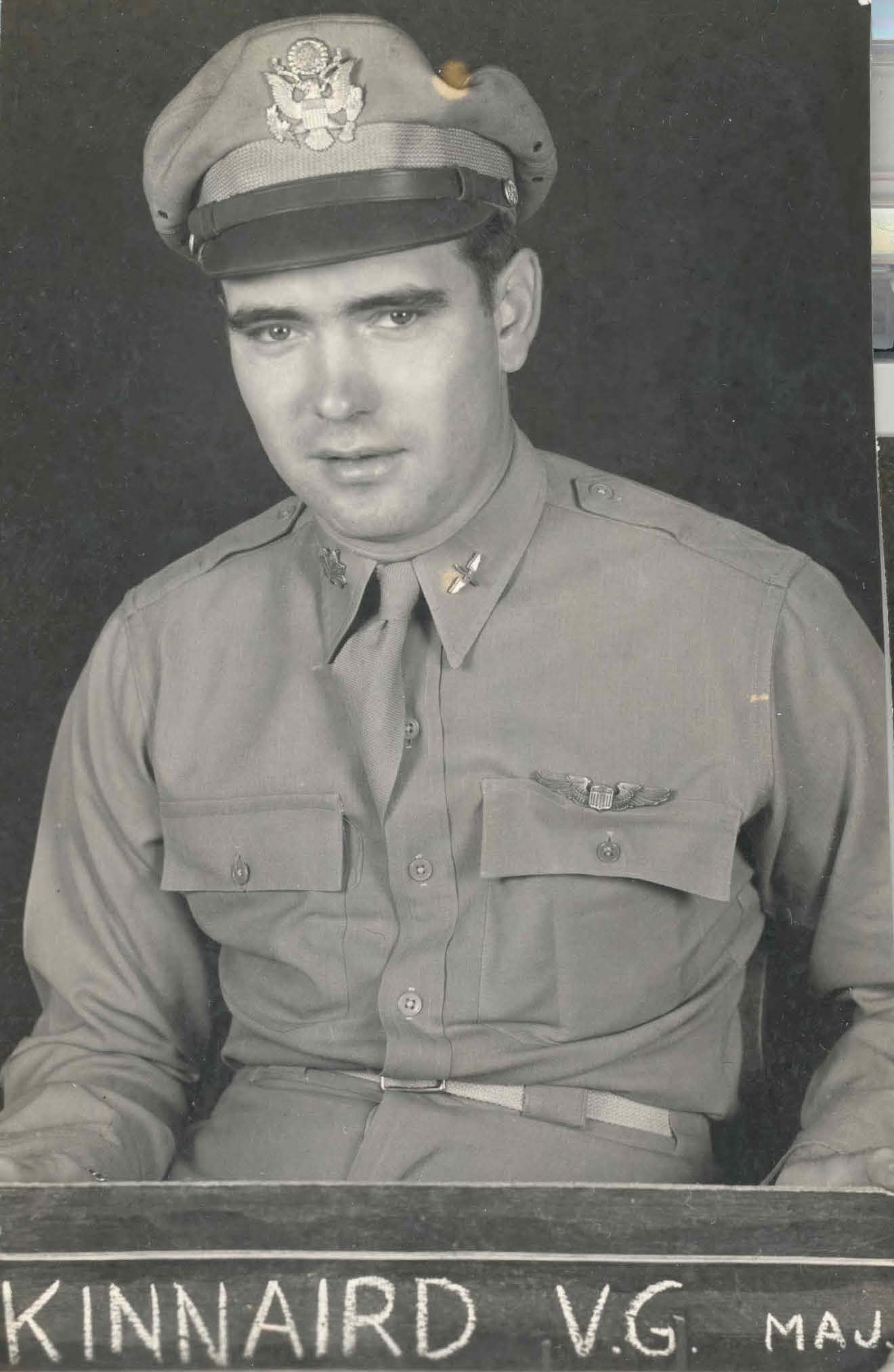

Rolling off the production line at Boeing’s factory in Renton, Washington, B-29A 44-61669 formally joined the US Army Air Forces on May 5, 1945; the bomber was with the 457th BS on Guam by that August. Like other squadrons within the 330th BG, the 457th had several spare aircraft, with 44-61669 being one of them. Though it received the identification code ‘K 15’, another aircraft also wore that same designator, this being B-29 44-69996 The City of Gary, IN. However, the latter aircraft was a write-off following a wheels-up landing on Iwo Jima on August 8th, 1945. Oddly enough, 44-61669 had suffered a minor mishap at North Field just a few days earlier on August 2nd, although damage was minimal. The 457th Bomb Squadron’s Operations Officer, Virgil Kinnaird Jr., regularly served as ‘669’s aircraft commander, and indeed he was at the helm on November 1, 1945 when 44-61669 flew home from Guam to the United States.

Oddly enough, given her present location, the late 1940s would see 44-61669 reassigned to the 2nd BS, 22nd BG, 22nd BW then stationed at March Air Force Base in Riverside, California. For a period, 44-61669 was temporarily assigned to Kadena Air Base on Okinawa, before another transfer, this time to the 19th Bomb Group at Andersen Air Force Base (formerly North Field) on Guam, where the aircraft had served briefly in WWII. During the Korean War, 44-61669 was one of a dozen B-29s which belonged to the 581st Air Resupply Squadron of the 581st Air Resupply and Communications Group at Mountain Home Air Force Base in Elmore County, Idaho. The Air Resupply and Communications Group had an unusual role which involved the insertion, resupply and extrication of guerilla-type personnel during special operations. The unit was also responsible for executing psychological warfare (PSYOPS) via the delivery of articles, such as propaganda leaflets, over enemy territory.

With its wartime clandestine work completed, 44-61669 underwent conversion to become a TB-29A trainer, although it only served briefly in this role. On March 18th, 1956, the U.S. Air Force struck 44-61669 from their inventory, transferring her to the US Navy which moved the retired bomber to Naval Ordnance Test Station (now Naval Air Weapons Station) China Lake in California. Here ‘669 would become a ground target for weapons trials, alongside a host of other former U.S. Air Force B-29s. Fortunately, however, 44-61669 survived intact into the 1970s, long enough for the type’s historical value (and rarity) to rise sufficiently to warrant its preservation. The U.S. Air Force Museum took custody of the airframe in 1974, and granted permission to Yesterday’s Air Force (owned by the legendary warbird collector David Tallichet) to restore the bomber sufficiently for a ferry flight to one of the organization’s branches in Topeka, Kansas (this branch later reorganized as the Combat Air Museum). The group documented their recovery effort in a short film, 299 Foxtrot. On June 15, 1976, the B-29, now registered as N3299F, flew from China Lake to Barstow-Daggett Airport, where Tallichet kept many of his vintage military aircraft at that time.

Although intended for Topeka, ‘669 never actually actually made that leg of the journey. Instead, the B-29 lingered in storage at Barstow-Daggett until January 1981, when it made its final flight – this time to the March Field Air Museum in Riverside, California. For over 20 years, it wore the markings of B-29 44-27263, nicknamed Mission Inn after the famous hotel in downtown Riverside which was a favorite gathering site for pilots assigned to March.

In 2003, the museum decided to repaint the Superfortress as Flagship 500, markings which they believed (at the time) represented her original wartime livery. This aircraft was also named Three Feathers for a time and the fuselage’s right side bore a tribute to the 4th Marine Division, whose sacrifices on Saipan led to the capture of Isley Field (which the Japanese called Aslito Airfield).

Despite the B-29’s overall excellent condition, the harsh sunlight in combination with dust abrasion can take a toll on the external finish of any aircraft stored outside for long in this region of California. To mitigate this issue for the B-29, the March Field Air Museum brought together a team, made up of regular museum volunteers and interested members of the public, to polish the Superfortress. The wing topsides remained coated with paint, however, and it was during the removal of this paint that the restoration manager, Alex LaBonte, noticed the unusual vestigial markings mentioned earlier in this article. Using a few rolls of masking tape to properly discern these new details, LaBonte saw the bottom part of a ‘K’, a ‘1’, and a ‘5’. He and the other museum staff could not understand why these markings were there, so they scoured the internet for B-29 experts who could perhaps tell them what ‘K 15’ actually referred to. In doing so, they came across a website with an archive for the 330th Bomb Group, and here they discovered that B-29s in that group, and in particular the 457th bomb Squadron, bore markings with similar lettering – thus establishing a link to 44-61669, and finally disproving the notion that the aircraft was ever part of the 500th Bomb Group, let also the 883rd Bomb Squadron.

At around the same time, official USAAF documents resurfaced which confirmed that 44-61669 had actually served in the 457th Bomb Squadron. With this information in hand, LaBonte convinced museum senior staff that they had to refinish the B-29 in its original 475th BS markings, which is in keeping with the institution’s policy of representing their aircraft in accurate livery from their service lives.

The big question, of course, is how did 44-61669 become mistakenly labeled as Flagship 500? Well, as it happens, the serial numbers for these two aircraft were off by a single digit, with Flagship 500 being serial number 44-61668, rather than 44-61669 as once thought. On October 27, 1945, an Army Air Forces’ crew flew 44-61668 to the Boneyard at what is now Davis-Monthan AFB in Tucson, Arizona. A reclamation team began scrapping that aircraft on May 10th, 1954… meanwhile, 44-61669 was still in active service. Over time, confusion must have arisen over the serial numbers. With the two numbers being so close, it could simply have been a transposition error… such things happen very easily, and this is certainly not a unique case. With veterans of the 883rd Bomb Squadron and 500th Bomb Group and their families becoming aware of the existence of a B-29 which many believed had been a part of their unit, that error soon settled smoothly into ‘fact’. And had Alex LaBonte not pursued the airframe’s actual history with such vigor, it’s likely that the myth would have prevailed and 44-61669’s true history would have remained unknown. Although she may now wear the yellow K of the 330th Bomb Group, the very fact that 44-61669 is preserved today honors far more… it honors the legacy and sacrifice of everyone involved with Boeing B-29s during their service in defense of the nation.

The author would like to thank Alex LaBonte, who not only pursued the dogged historical research involved in discovering the aircraft’s actual service history, but has worked hard to lead the restoration efforts on this B-29.

I was very happy to provide you with all of the photos and documentation to prove that this aircraft was one of the 330th’s!

Awesome job on the resto!!

Thanks for your help!

Thanks, good article.

It really caught my eye because my father was in the Seabees and spent a year or two on Guam near the end of the war. He took many photos and had several of a B-29 with a similar tail code, Square O. They were a sister group to Square K. I posted his B-29 photos on airliners.net here:

https://www.airliners.net/search?aircraftBasicType=2461&user=13753&sortBy=dateAccepted&sortOrder=desc&perPage=36&display=detail

One short story: after I posted the photos, I got an email from a WWII B-29 veterans group. There was a controversy whether the letter in the square was bare metal (unpainted) or yellow. They were very happy to see the yellow letter that settled the issue. I guess black and white photos of the time weren’t able to show the differences between bare metal and yellow.

Actually.. your vets are partially correct. Initially, April to June 1945, the ‘box’ letters of the 314th BW were BMF.., never filled with white. In late June/ early July in order to add more recognition when swarms of B-29’s were trying to assemble over rally points prior to the bomb run.., the box letters were infilled with a very bright orange/yellow paint. Just as you see in this restored B-29 in the photos above.

I believe my grandfather was the pilot of the k-15 when it had its hard landing. He was in the 330th and 457th and flew out of north field. He used to tell us stories of getting his engines shot out and bracing himself for a hard landing by putting his left hand in the window frame- then upon impact the window shot forward and broke his hand. He told us the tower was mad at him for landing on the runway because of how busy it was- I think I have a photo somewhere of cranes hauling the plane off the runway.

We have a few photos in storage from his time there I’ll have to dig out. I did a Google search and found this article because the family was debating the nickname of his plane. Nobody seems to be able to remember.

Enjoyed reading about this!

Annie, please email me below as I am/was the historian for the 330th and should have info to help you.

Regards,

S.

You can reach me at “[email protected]”