There are many among us who would love to own and restore a vintage aeroplane, but few of us have the resources to accomplish it by ourselves, either financial or technical. Even fewer have the drive to get it done. It is this last asset which is probably the most vital. Determination to succeed will always trump technical skill and dollars. Nils Andersson, an airline pilot based in Germany, has seemingly inexhaustible determination. In just two years he has almost single-handedly restored the forward fuselage of a Sud Aviation Caravelle jet airliner from a corroded hulk into a beautiful and highly sophisticated flight simulator, in which nearly all of the original controls, instruments, switches, and indicators are fully functional, and integrated into the modern computer system.

The Caravelle is one of the earliest jet liners, and played a very significant role in the early days of jet-powered passenger service during the 1950s and 60s. Of the nearly 300 examples built, relatively few remain sadly, which makes it all the more important that Andersson has rescued a cockpit section.

The scope of Andersson’s work on this project is so large, we thought it would be best to cover the story in his own words through an interview we conducted recently. In addition to our interview, Andersson created a fascinating and very well produced twenty minute documentary on the Caravelle and his project. We have added the link to this impressive film at the end of this article.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

WN: Perhaps first you could tell us a little bit about yourself, and how you got involved in aviation.

Andersson: The whole family has been working in the aviation industry for generations. My grandfather, uncle and aunts work/worked for SAS (Scandinavian Airlines). My father flew for Lufthansa, and my mother with Air France on Caravelles and 707s before joining BEA and later Lufthansa as well. We lived in Toulouse, France, the heart of European civil aviation, and my father was a test and intructor pilot for Airbus. It was a fascinating environment to grow up in. My brother and I followed our father’s steps and are now commercial pilots flying Airbus wide-body jets. Though times have changed dramatically in aviation over the last twenty to thirty years compared to the career our parents had, it is still a great field to work in.

WN: What made you choose the Caravelle to restore?

Andersson: I have long held a passion for first generation jetliners, but the Caravelle was always my favourite. Its clean, elegant lines make it look so airworthy; a work of art. Caravelles were frequently flying in Toulouse during the 1990s when I lived there, and whenever I saw one I always stopped and looked up in the sky, enjoying the shape, noise and smoke.

WN: Can you tell us a little about the history of this specific Caravelle? When it was made, where, and which airlines it flew with?

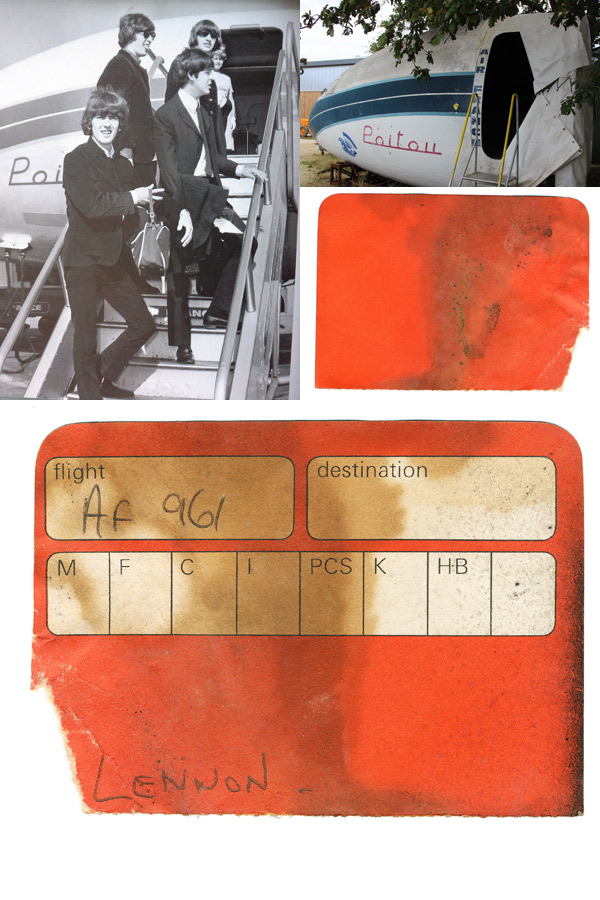

Andersson: The Caravelle I am restoring was built in 1960. While it has the serial number 58, it was actually the 60th Caravelle built. It flew for the first time on November 3rd, 1960 and joined Air France on November 10th, 1960 where it gained the name ‘Poitou’ after a region in western France. It entered commercial service three days later, flying between Paris-Düsseldorf-Hamburg-Düsseldorf-Paris. ‘Poitou’ remained in service with Air France almost until the end of the Caravelle era with the carrier, which came to a close in March 1981. ‘Poitou’ flew her last paying passengers on August 28th, 1980 traveling from Schipol in Amsterdam to Charles de Gaulle airport in Paris. The same day, she made her final flight to Paris, Orly and retirement, with 37,028 flying hours and 32,207 landings in her logbook. The scrappers cut off her forward fuselage, but disposed of the rest of Poitou’s carcass between November and December 1980. An air traffic control center near Paris-Orly airport intended to have the cockpit converted into a simulator, but abandoned the project due to costs. Thankfully, volunteers from an aviation museum discovered the cockpit section on its way to the scrap man and rescued the forlorn artifact.

By 1994, the nose section had moved to La Ferté-Alais, near Paris and went on display at an aviation collection. It later ‘starred’ in the French movie “Belle Maman” with Catherine Deneuve. By 2003 it was in storage outside, under a tree. Sadly its condition deteriorated quickly after that.

During the disassembly process, I disovered two intersting artifacts: A first class boarding pass with the name “Lennon” written on it. Some research revealed a photograph showing the Beatles climbing on board ‘Poitou’ for a flight from Manchester to Paris in June, 1964, so it’s very likely that the card belonged to none other than John Lennon. A flight attendant probably kept the card as a souvenir, and lost it in the forward galley. The card lay hidden between the cockpit and galley wall for over 45 years! Another artifact I found was a gold ring. It was hidden in the carpet below a metal rail.

WN: When did you acquire the project, and how long have you been actively working on it?

Andersson: After months or research and negotiating with several Caravelle owners I was able to purchase ‘Poitou’ in September, 2012. I had simply made them an offer to buy it after explaining my passion for this particular aircraft. By November 2012, I had it moved to Munich from Paris and have been working on it daily ever since. It is such an enormous project that covers so many aspects of interests and there is always something to do from doing wiring diagrams, researching, programming – so work you can do while on the road. I try to work around 10-40 hours on it per week depending on my social life and job. The cockpit is located in a 100m² hangar 40km east of Munich in the lovely Bavarian countryside. Surounded by horses and cows the cockpit will be moved to a new location closer to the city when major restoration works are complete. Every now and then a friend, my brother or girl friend helps out but I am doing 95% of the work myself. However I have two very competent consultants with engineering backgrounds and there is literally no problem that cannot be solved using their help.

I am in touch with two enthusiast groups as well. One is the Le Caravelle Club (www.lecaravelleclub.com) in Sweden which has the last operational (but not airworthy) Caravelle in the world. They kindly granted access to their aircraft and documentation. The other organization is a group of volunteers in Avignon , France that, little by little, is restoring a complete Air France Caravelle (www.caravelleguyane.fr). We exchange parts and manuals and help each other where ever we can.

WN: What have been the most difficult aspects of the project so far?

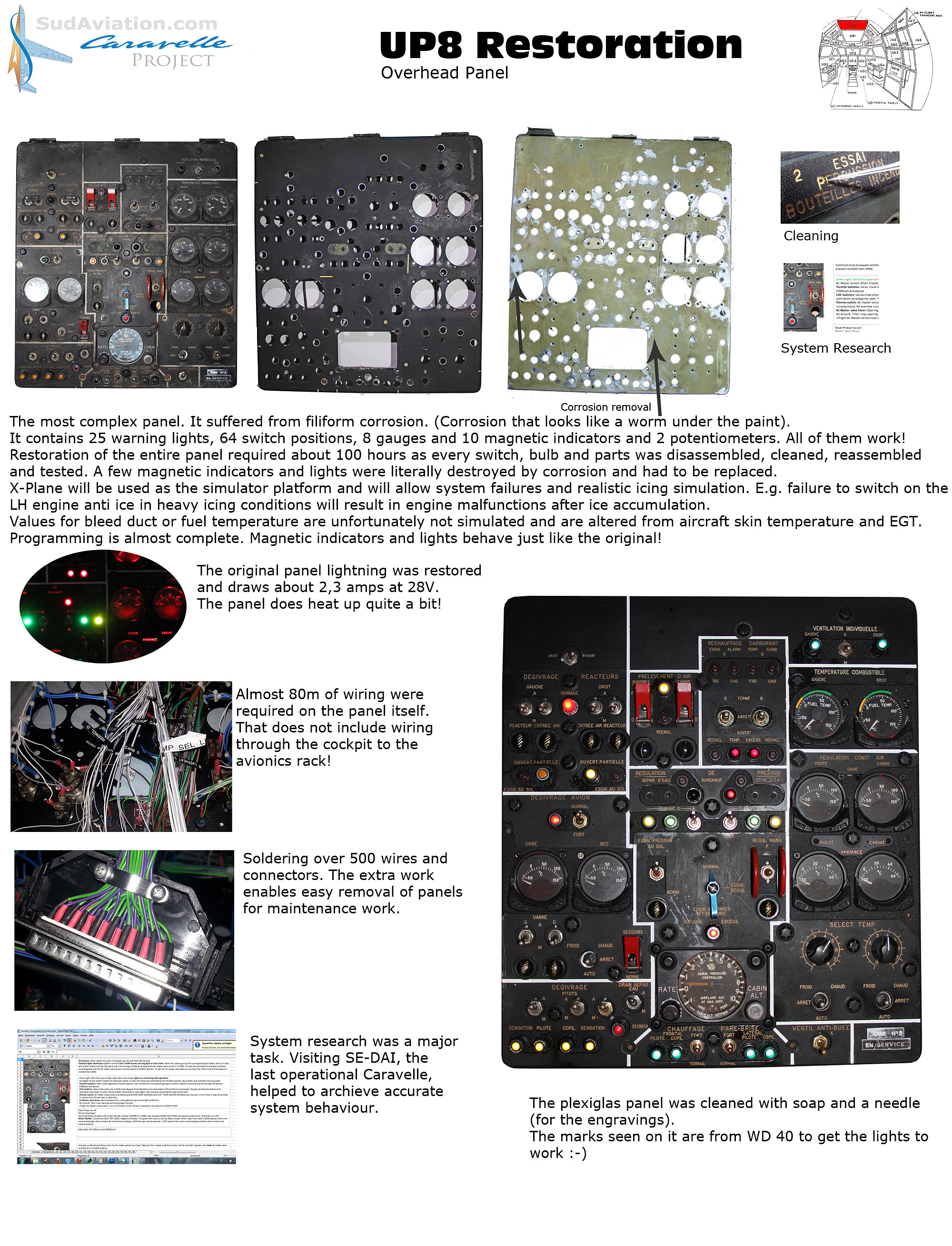

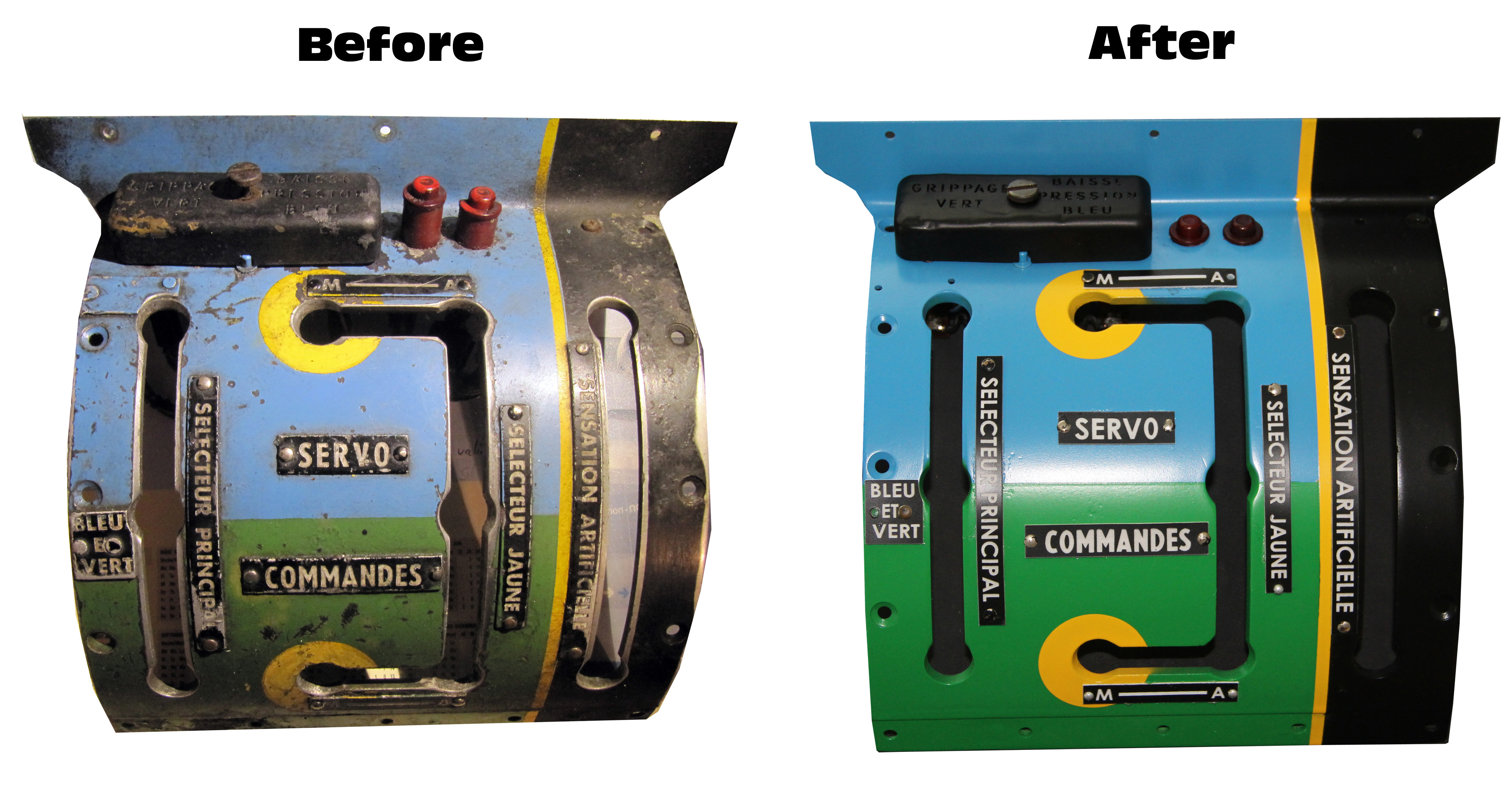

Andersson: There were so many! Teaching myself how to connect, interface and programm switches, lights and gauges with the computer and flight simulator software. That was the steepest learning curve. Less of a difficulty but a more time consuming process has been polishing and corrosion removal. Pervasive corrosion had formed everywhere in the cockpit since it was stored outside for decades. It required almost a complete year to complete this phase of the project.

Perhaps the biggest hurdle to overcome was finding a low cost solution to lift the cockpit off its trailer to work in the wheel well and polish the lower side of the fuselage. I managed to do it using a pallet lifter, bricks, twelve bolts and two large wooden bars.

Polishing required several hundred hours using a simple drill and polishing disc. It was the dirtiest work you can imagine. After eight hours of polishing your skin turns pitch-black from the polishing dust. Using resperatory protection is of utmost importance. Once polishing was complete, repainting was the next step which turned out to be more difficult than initially thought. First of all, finding the right colors was tricky. Sud Aviation and Air France’s Caravelle paint manufacturer no longer exists and their colour code has turned out to be useless. Using original paint and a professional car painter we were able to get the colours spot on. But finding sombody who would paint the cockpit turned out to be even more difficult. Car and aircraft painters rejected or would charge astronomical amounts of money. So I had to teach myself how to paint. Using Youtube DIY videos as a guide, over the course of a year, I periodically practised painting on large and small parts. In September, 2014 I finally felt ready to go ahead and started painting. The paint job turned out very nice. Unmasking the painted cockpit is a moment of complete satisfaction and it justifies all of the investment in time, effort and money to that point. It is worth mentioning that Air France kindly supplied the titles and logos which were manufactured to the original specifications.

WN: Are there any components you are still looking for to complete the project?

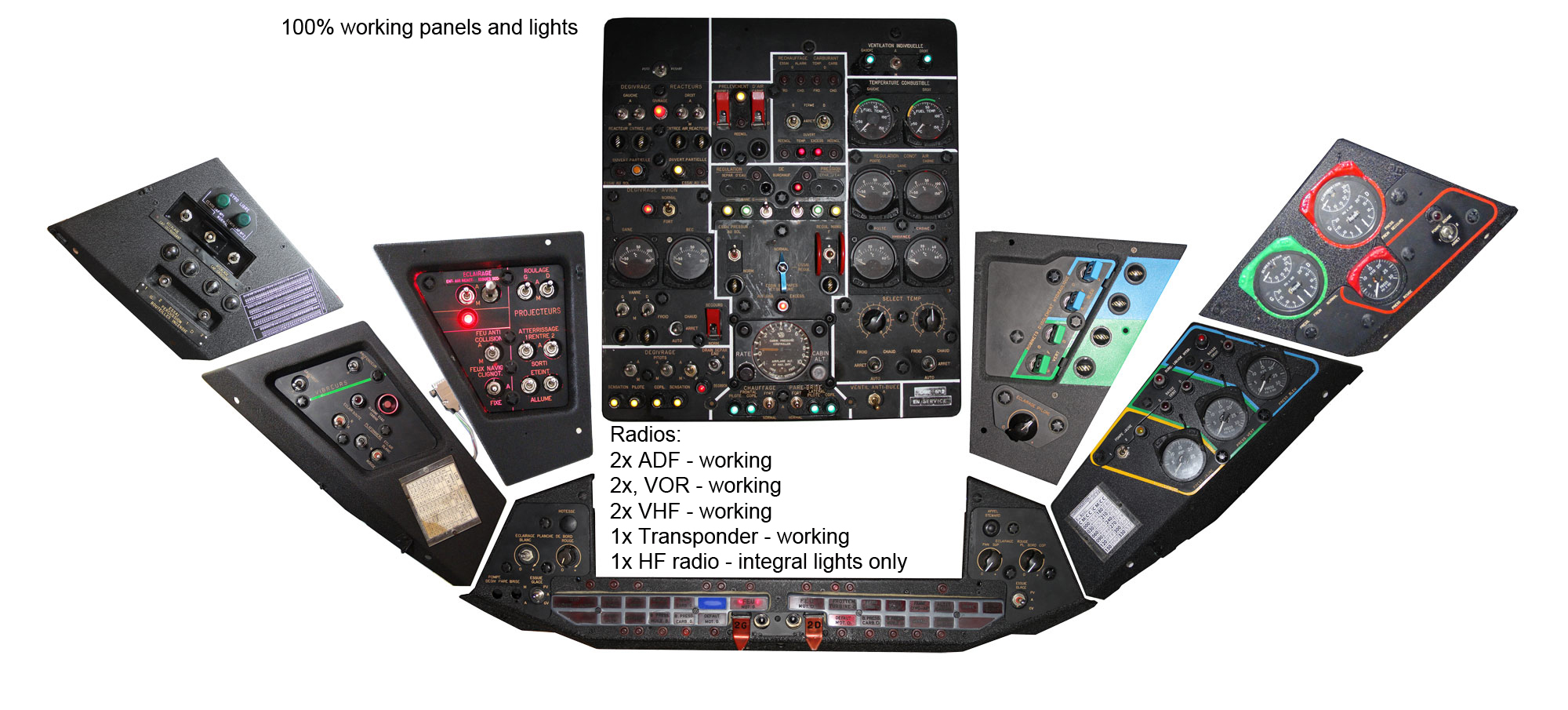

Andersson: Luckily the cockpit was almost complete when I got it, but it turned out that 15% of the switches, gauges and light assemblies were inoperative. I already had a large number of Caravelle parts and panels and was able to replace almost all of the damaged parts from that collection. The observer and flight engineer’s seats were missing, as were the avionics rack covers. I was able to find an original Air France Caravelle obersever seat in an online auction, and received the donation of a flight engineers seat from TFC Käufer of Germany, a company specialized in the manufacturing of aircraft cabin trainers. But for the avionics rack covers, the cockpit is not missing any parts except one middle marker light cover.

WN: What are your plans with the project when it’s done?

Andersson: Complex machinery such as a flight simulator is never really done as there is always something to improve or repair. The aim is to create the most realistic Caravelle simulator ever built. Every switch, knob and gauge will work and the flight dynamics and control forces are going to be spot on. This is possible thanks to the 10,000+ pages of maintenance manuals which answer literally every question that arises. Once complete, the estimate is in 2016, the simulator will recreate in detail the experience of flying a first generation jetliner. Simulator flights will be offered to the public to cover some of the enormous expenses of this project. It will educate and entertain and become a living piece of aviation history. There is a great satisfaction in fullfilling a childhood dream and seeing the image you have in your mind turning slowly into reality. If I still have the time and money, my next project is going to be a Boeing 707 cockpit, but not before 2016, and certainly not as big again.

WN: How will you be configuring it as a simulator?

Andersson: Basically what I am doing is tapping the data from the flight simulator and manipulate it with the switches and levers. The flight simulator software simulates thousands of parameters from weather to navigation and aircraft systems. All we do is read out the data we need, convert them into electrical signals and display them on the gauges, lights or warning horns. Eventually the real cockpit runs in parallel to the simulated cockpit. Failures and malfunctions will be a very important part of the simulator. Bird strikes, smoke, engine malfunctions or instrument failures – all original warning horns and fire bells are reconnected and will sound when a particular failure occurs. As an airline pilot myself this is what is actually the most fun when flying a simulator.

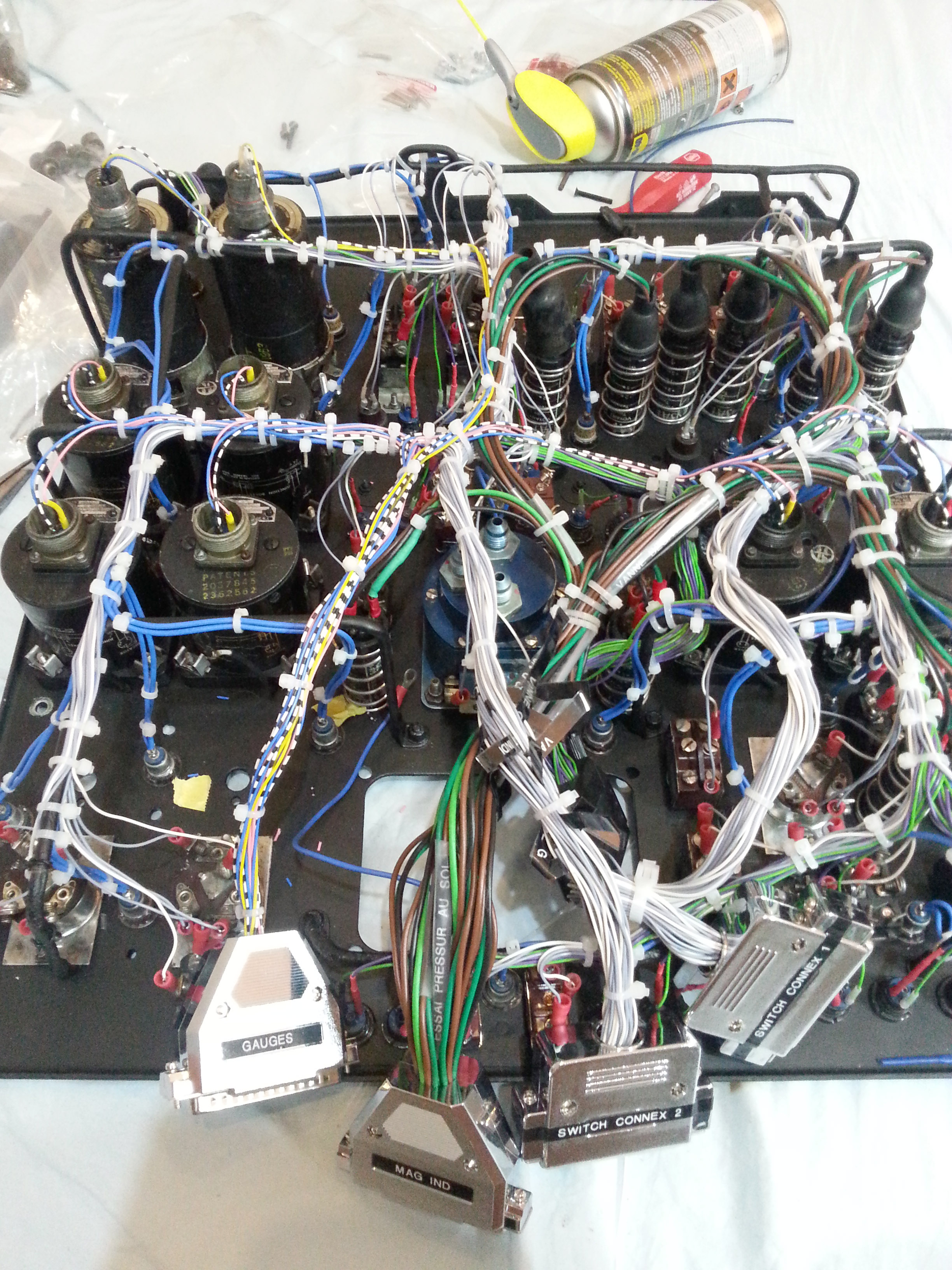

Before I started I set up a wiring standard for all panels. Every panel is sandblasted and repainted in its original wrinkle paint. Each light, switch and gauge is carefully tested before being reinstalled. All wiring is documented for easy maintenance and trouble shooting. The required functions are then programmed and all switches linked to the flight simulator. The panel is then wrapped in plastic awaiting installation. So far all 24 panels, consisting of 240 switches, 84 warning lights, 45 magnetic indicators and 180 circuit breakers, are reassembled, tested and partially programmed. Focus is now set on the instrument gauges. Some gauges can be interfaced but others are inoperative or running at 115V/400Hz which will not be used in the cockpit for safety reasons. For the gauge conversion I am using stepper motors commonly found in automobile dashboards. Running at 5 Volts these are very reliable, cheap and have a high resolution. The radios have already been converted for simulator use by stripping the electronics and replacing them with potentiometers and some programming magic.

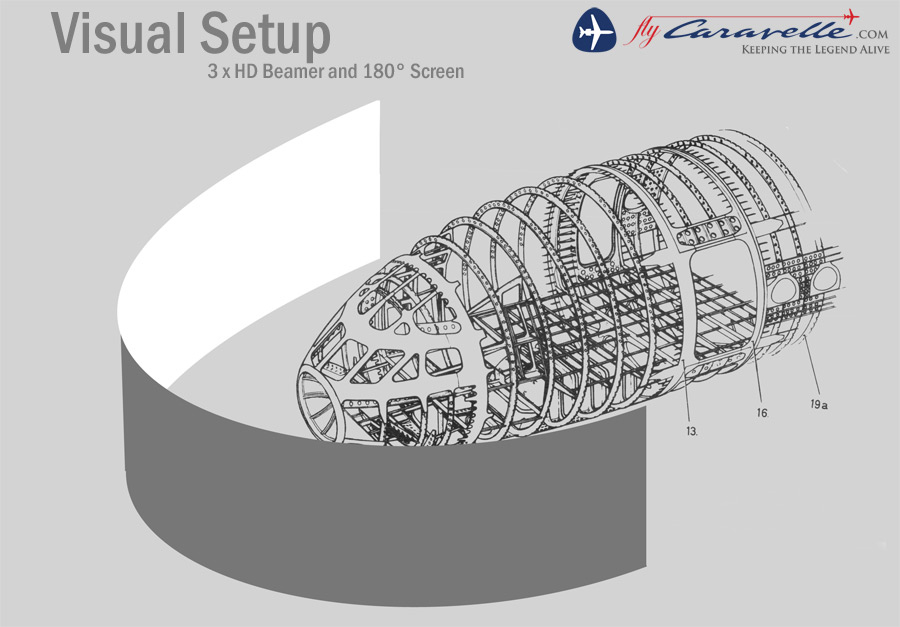

The next steps are reconnecting an environmental system, installing control loading, wiring and the smoke/oxygen system. Vibrators in the seat will give a realistic impression of aircraft vibrations but the key element of the simulator is going to be the giant 220° curved panoramic screen built around the nose section. The panoramic image is archieved by blending together the images of 3 projectors. This fairly cost effective solution will create a full immersive view when sitting in the cockpit allowing the simulator pilot to look through the old windscreens. Due to the size and weight of the cockpit, it will never be installed on a motion platform which would also require a different appraoch to many instrument and radio rebuilds because of vibration issues.

The cockpit and exterior aren’t the only areas to receive tender loving care. The cabin will also be refurbished into its original 1970s look. The area behind the cockpit was used as the galley and wardrobe, but they no longer exist. This free space will be used as retro briefing room with flat screens and original 1960s carpet and wall art. I had the carpet remanufactured to match the original Air France carpet, even the 1960s wall art will be spot on. After all, it is the aim to re-create the impressions that a visitor to the world’s first short haul jet airliner would have had when he or she first stepped into the Caravelle – an exciting moment. To enhance this experience a Fokker 27 stair has been aquired. This will probably be the world’s only simulator that is boarded via an original aircraft stair through the aircraft’s main entrance door.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

And that concludes our article. WarbirdsNews wishes to thank Nils Andersson profusely for his contribution here, but especially for the amazing project he’s brought to fruition. We look forwards to seeing it when it’s finally completed! And now please do watch Andersson’s amazing video on his project below…

Nils. This is absolutely stunning.

Keep going it will be worth every bit of effort you put into it.

Deryck.

I would love to restore a vintage aeroplane myself !

I was stationed in Keflavik, Iceland in 1961/1962 when a Caravelle in United Airlines livery stopped to refuel. I have a pic of it on the tarmac somewhere among my 35mm slide collection.

Really a beautiful plane.

Norm

Nils, Fantastic restoration of the CVL cockpit section, one of my favorite planes. As a young man I worked for United at ORD where

the checks were done. I was working the day that our first one arrived from France. N1001U which now sits in the Pima Air Museum at Tucson, AZ. Though not a mechanic I worked in the offices and maintained the maintenance manuals for all the UAL planes, among other duties. One of the mechanics knew I collect old plane stuff and gave me a book that has a lot of pages of our version of Suds neat plane. I have precious few pictures taken in the hangar when, I think it was N1016U was in for maintenance. My stash of airline parts is pretty small and of course you have the

ultimate, but I do have a really small part of one of our Caravelles,

namely a blue room door hinge. We called the toilets ‘blue rooms’ and the complicated hinges that would lay the door against the wall to allow as much space for passengers to pass going from the airstair to their seats. Those fancy hinges had a flaw where the would break, then get pushed hard to get them closed really breaking them. UAL decided to replace those undoubtedly costly hinges with common (I’m sure aircraft quality) aircraft piano hinges. During the changing process there was a pail of the broken ones waiting for a ride to the dumpster… I confiscated one and probably have one of only a few in the world. So there I got my piece of a Caravelle. Most folks laugh at me when I show it to them but I do have a piece of one of those beautiful planes. I’ll see if I can’t dig out the pix on our hangar and get copies to you if you’d care for them. Oh, yes I was working the day Number One N1001U, that’s in Pima Museum, arrived at ORD. I had a lousy camera that double exposed, but there’s not many pictures of that arrival. I only rode on 2 flights via CVL but it was a neat plane. Don’t forget to put a soft bumper on the forward passenger door, we had yellow ones that slipped on the upper part of the forward door so folks didn’t get their foreheads creased as the door was rather short… Have fun, it sure looks like your in the midst of that now. Later, Jim Martin who lives near Madison Wisconsin and has to do with the EAA airshow at Oshkosh for about the last 40 years. Ever been there?