Translated report – Many thanks to José Manuel Gil, ‘Sandglass Patrol’

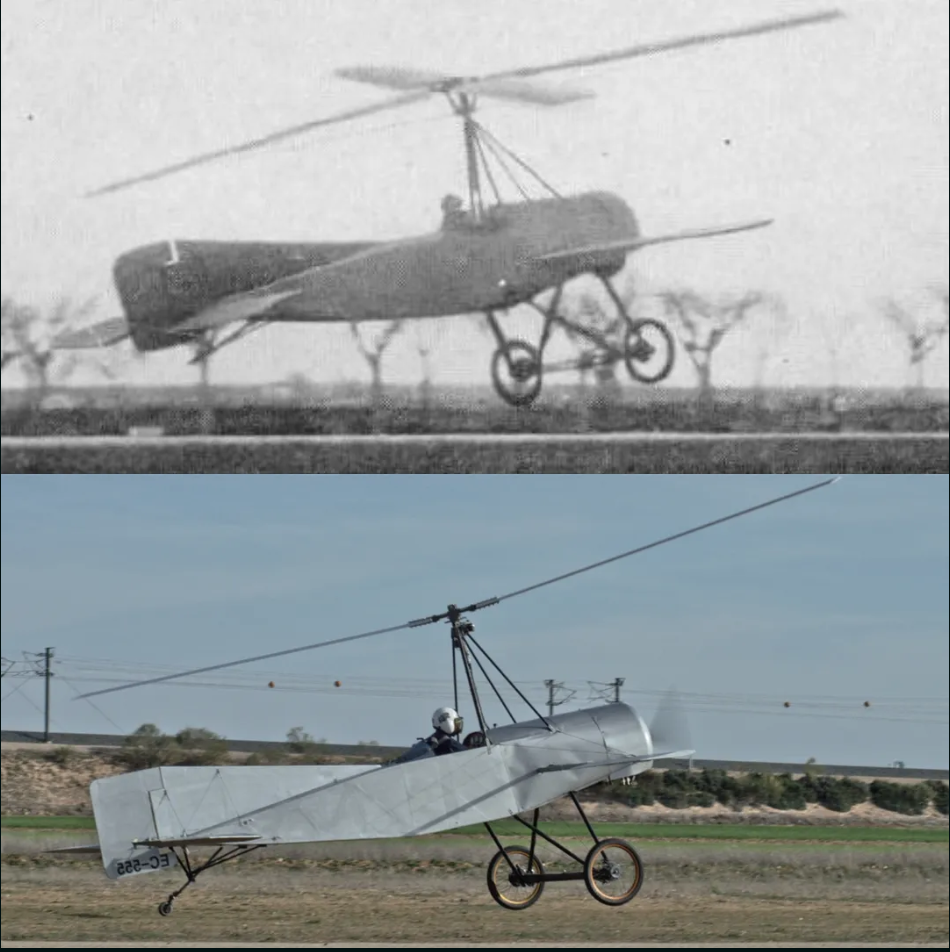

Just two months past the centenary marking the first successful autogyro flight, a modern replica of that same aircraft, a Cierva C.4 Autogiro*, flew on March 29th, 2023, in Ocaña about forty miles east of Toledo, Spain.

The project is the result of a decision by a group of friends at the Getafe Ultralight Club to commemorate the centenary of Juan de la Cierva’s historic first flight in his C.4 during January 1923. Following more than a thousand hours of design and fabrication work, the replica C.4 was ready for its official unveiling in January at Getafe Air Base, not far from the very spot where the original had first taken flight a hundred years earlier. The public unveiling took place at Camarenilla aerodrome this March, but the team chose to move the aircraft to Ocaña for its first flight. They disassembled the replica C.4 in the morning, driving it to the historic Ocaña Aerodrome by truck and then reassembling it.

Initial ground tests without the (unpowered) main rotor fitted, were carried out to check the engine operation and to test the aircraft in high-speed taxiing. After the crew fitted the rotor, a test run took place just a little after 6:00 p.m. local time. Pilot Fernando Roselló began the taxi run – but the autogiro lifted off briefly and then landed gently.

After this small jump, other takeoffs followed, until, finally, the Cierva took off and completed a couple of full circuits. Nerves, illusion and adrenaline were rewarded by seeing the autogyro take off from the ground without incident and land again successfully. The replica of the first successful autogyro is now flying!

This particular early model does not having direct control through the inclination of the rotor hub, but rather still retains roll and elevator control with ailerons and rudder. While the replica C.4 stays true to much of the original design concept, the replica team chose to include some safety concessions, such as a modern engine and a well-proven, two-bladed rotor design (in place of the original four-bladed system which had only a marginal useful life of just a few hours flight time). One of the team engineers added that the rotor system, as it is without direct control, is based on Cierva’s patent, number 100595 of Dec 1926!

After alighting, Fernando Roselló stated that the aircraft behaved just as he had expected. It is a very stable aircraft, but since it lacks direct control (using aerodynamic control instead) it is slower to respond to control input. He flew as slowly as 50km/h and estimated a cruise of about 80km/h at about 4,500rpm, comparing it to 4,700rpm on his 80HP Rotax powered 912 gyroplane which flew at 80km/h with a positive variometer (rate of climb indicator).

The Original C.4 in History

by James Kightly

Like many aviation pioneers, Spaniard Juan de la Cierva sought a way of developing a ‘safe’ aircraft and decided to attempt this by developing a rotorcraft, which would retain the wings’ airspeed irrespective of the aircraft’s forward speed. His first three designs were unsuccessful, due to issues with managing the (unpowered) rotor, but his fourth – the C.4 – achieved the first recorded flight of a powered, self-lifting autogyro in January 1923. It was flown by Alejandro Gomez Spencer at Cuatro Vientos airfield in Madrid, Spain.

The specific breakthrough was fitting the rotor with ‘flapping’ hinges, enabling each rotor blade to move up and down, compensating for the difference of lift and airspeed with advancing and retreating blades in forward flight. When the C.4’s engine failed shortly after an early test flight takeoff, the pilot brought the aircraft to a safe autorotating landing, proving one element of the type’s safety concept.

Cierva, alongside colleagues he collaborated with frequently, achieved many more developmental steps, and these advances fed into the later success of the helicopter, which used many of Cierva’s breakthrough ideas in rotor design. A helicopter, of course, uses a powered rotor arrangement, which is the vehicle’s fundamental difference with the gyroplane, which features a free-wheeling rotor. As a consequence, helicopters typically offer significantly greater performance, but gyroplanes are far less complex and expensive to manufacture or maintain.

Tragically, and somewhat ironically, Juan de la Cierva y Codorníu, 1st Count of la Cierva, died as a passenger in a fixed wing aircraft when the KLM Douglas DC-2 he was aboard crashed soon after take off from Croydon Air Port near London, England on on a foggy morning, December 9th 1936.

Report and photographs with many thanks to José Manuel Gil, Aerospace Engineer, light aircraft pilot, blogger and podcaster at https://blog.sandglasspatrol.com. Please follow José’s blog for more details in Spanish.

*The type is known as an autogyro or gyroplane. Juan de la Cierva named it the ‘autogiro’ originally, later patenting that spelling, which is thus correct only for use with Cierva (and derived) examples.

James Kightly, from Melbourne, Australia, discovered his passion for aviation at the Moorabbin collection in the late 1960s. With over 30 years of writing experience for aviation magazines in the UK, US, Australia, and France, he is a feature writer for Aeroplane Monthly and an advisor for the RAAF History & Heritage Branch.

James has interviewed aviation professionals worldwide and co-runs the Aviation Cultures conferences. He has flown in historic aircraft like the Canadian Warplane Heritage’s Lancaster. At Vintage Aviation News, he ensures accurate and insightful aviation history articles.

Outside aviation, James has worked extensively in the book trade and museums. He supports the Moorabbin Air Museum and the Shuttleworth Collection. James lives in rural Victoria with his wife and dog.

What an achievement for the whole team.Dave