Restoration of the Dakota Territory Air Museum’s P-47D Thunderbolt 42-27609 is progressing well at AirCorps Aviation in Bemidji, Minnesota, as Chuck Cravens’ December 2021/January 2022 report reveals. We thought our readers would love to catch up on the latest details so, without further ado, here goes!

Update

The turbosupercharger system, wings, firewall-forward section of the fuselage (including the cowl), and the control surfaces were all part of the restoration work this month.

Turbosupercharger System

The turbosupercharger system continues to be a focus of the restoration effort. This system gave the Thunderbolt remarkable tactical flexibility. The aircraft was capable of performing both high altitude bomber escort and low level fighter bomber missions because of the power which the turbosupercharged Pratt&Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp could provide in those environments.

Fuselage

Most of the fuselage-related work this month involved firewall-forward components, encompassing the engine accessory area, cowling, and the QEC or Quick Engine Change unit.

Engine and Accessory Section

The induction vibrator is necessary because it provides a strong spark before the magneto has reached the rotational speed required for normal engine operation. It helps start the engine and operates through bypassing the magnet portion of the magneto, instead supplying the primary coil of one of the magnetos with a pulsating stream of DC current drawn from the battery.

As the engine cranks during start up, these high voltage pulses travel to the distributor as a “shower of sparks” and from the distributor to the spark plugs themselves, firing up the engine.

QEC (QUICK ENGINE CHANGE)

One of the engineering techniques which enabled rapid maintenance turnaround during WWII involved creating a QEC, i.e. a Quick Engine Change unit, which combined the assembly of the engine, its mount and many of its linkages and accessories into a single unit which could be more readily installed or removed from the airframe. Early B model Thunderbolts did not have this feature, and as a result, maintenance crews found engine changes excessively time-consuming. Republic responded with a design change first incorporated into the P-47C-1RE. They extended the fuselage by an extra 8 inches to allow for a QEC, an update which amounted to the first major change to the P-47’s airframe. Oddly enough, as a byproduct of this extension, the aircraft’s handling qualities also improved!

The QEC assembly meant that the engine and mounts could all be removed as a unit and replaced with a new QEC assembly, saving as much as 60% of the time required for an engine change.

Wings

Structurally, the wings are essentially complete, so work on their internal systems, access doors and control surfaces occupied much of the restorers time this month.

Control Surfaces

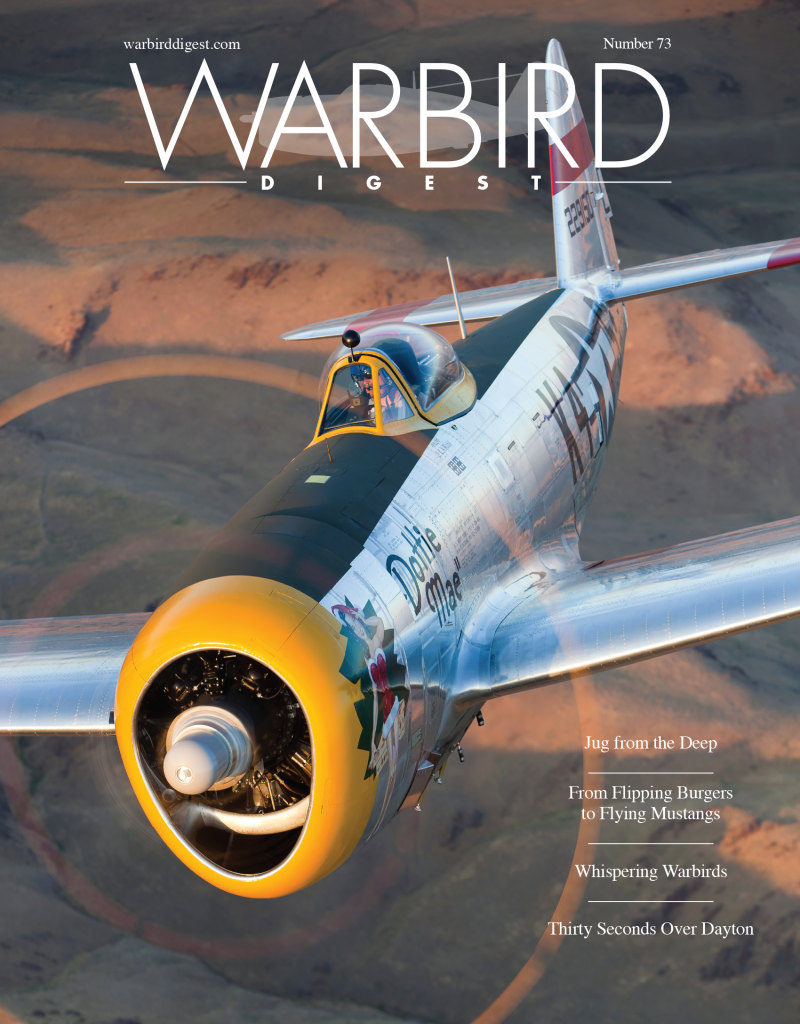

With the primary structures for the fuselage, wings and empennage now completed, the control surfaces remain the last large assemblies to undergo completion. The rudder is now done and it has been test-mounted as the cover photo shows. One of the flaps is now also complete; it has been function tested as well. Work on the remaining flap and the elevators continues.

Flaps

One sign of progress is that a flap has been installed and operated this month. P-47 flaps are large, and comprise roughly 13% of the projected wing area. Their design follows the NACA slotted trailing edge type. Slotted flaps like these open a slot between the flap and the wing; allowing high-pressure air from the bottom of the wing to flow through the slot to the top surface of the wing. This design delays airflow separation by energizing the boundary layer on top of the wing; it adds lift without excessive drag. Hydraulic fluid pressure operates the flaps, through three trapezoidal linkages which are synchronized via a torque tube which connects them. This system pushes them aft first, and then down.¹

¹ Pratten, Garth (2016). “’Calling the Tune’: Australian and Allied Operations at Balikpapan”. In Dean, Peter J. (ed.). Australia 1944–45: Victory in the Pacific. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. pp. 320–340.

Cowl

Cowl flap work continues.

Fifth Air Force P-47 Tactics in the SW Pacific

When the P-47 first arrived in the SW Pacific theater, pilots met the type with a great deal of skepticism. General Kenney had requested more P-38s because, compared to other USAAF fighters, the P-38 had superior range, speed, and its two engines provided a safety margin during the long, overwater flights which missions in the SW Pacific required.

US war planning in 1942-43 held that the war in Europe should take first priority. This meant that aircraft shipments to the Fifth Air Force would be based on what was available after ETO demands were satisfied. Operation Torch in North Africa also had priority for P-38 shipments, and even the 8th Air Force in Europe was stripped of its P-38s for that effort.

No P-38s were available to General Kenney, so he was offered more P-40s. P-40 performance was marginal in combat with the Japanese fighters in the area and its range was limited. The P-47’s range was even more limited without drop tanks, but it had speed and altitude performance advantages over the P-40 and P-39s which the 5th AF then operated.

The first P-47 unit, the 348th Fighter Group, arrived in Australia on June 30, 1943. Experimentation for increasing the combat radius for their P-47D-2REs began immediately.

These experiments resulted in the 200-gallon belly tanks, designed and manufactured in Australia, and the notorious Christmas tree tank mounted internally behind the pilot; 42-27609 has this field modification. While the belly and Christmas tree tanks improved the P-47’s range, they still needed more so, in the summer of 1944, as the Japanese pulled back from Papua New Guinea and bombing attacks on oil installations in Balikpapan increased, the P-47 units loaded up their aircraft with three drop tanks!

The addition of these drop tanks widened the P-47’s combat radius to as much as 750 miles.

This provided an answer to unescorted bomber losses in raids to Balipapan on the island of Borneo, part of the Dutch East Indies. The need for a long range escort in this area was directly related to the enemy’s supply of petroleum. Some estimates state that 35% of the refined petroleum products and as much as half of the aviation fuel which Japan used in WWII came from refineries in the Dutch East Indies.

“In late September and early October 1944, the US Thirteenth and Fifth Air Forces began long-range bombing raids from Noemfoor. The first two raids suffered heavy losses due to the lack of escort fighters and inflicted minimal damage; however, after a brief pause and a change of tactics by the US airmen, the final three raids resulted in heavy damage to the refineries and the destruction of most of the Japanese aircraft defending.”²

These and other long range missions demanded specific tactics to achieve success.

² Pratten, Garth (2016). “’Calling the Tune’: Australian and Allied Operations at Balikpapan”. In Dean, Peter J. (ed.). Australia 1944–45: Victory in the Pacific. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. pp. 320–340.

Major John R. Young describes maximum range mission tactics in Ray Merriam’s book Fighter Tactics in the Southwest Pacific Area. The mission Young describes involved a long-range fighter sweep to clear a target area ahead of a B-24 Liberator bomber force. The target was 835 statute miles from their base at Morotai, Netherlands East Indies. This necessitated hanging three external drop tanks on the unit’s P-47s: two wing-mounted 165 gallon tanks and a 75 gallon centerline tank.

The Thunderbolts on this extreme range mission drew fuel from the large wing tanks until they were emptied or combat necessitated dropping them. Interestingly, to return home from a long range mission like this, the pilots would not drop their centerline 75 gallon tank during combat. This was a highly unusual practice because, in almost all other cases during WWII, aircraft punched their drop tanks immediately when combat was imminent. Dropping tanks had several desirable outcomes; it improved flight performance and maneuverability, and also greatly reduced vulnerability to fire or explosion should these tanks take hits from enemy munitions. In fact, if a drop tank failed to detach during such circumnstances, the pilot was usually ordered to return to base rather than engage in combat with the tank still attached.

However, on a maximum-range mission, it would prove impossible to return to base without using the remaining fuel in the P-47’s centerline tank, so the risk was deemed worth taking. It is also likely that opposition to such protocol at this late stage in the war was far less fierce than it had been when Japan’s cadre of fighter pilots comprised a force of experienced veterans. By late 1944, many of Japans remaining fighter pilots were very green, and therefore less of a threat.

While it isn’t clear from Major Young’s account as to precisely which P-47 variant he was flying at the time, it was most likely a D-25, with slightly increased internal fuel capacity in comparison to the D-23 version.

In the same book, Captain Leroy Grosshuesch of the 39th Fighter Squadron describes another mission. He specifically mentions the P-47D-16, D-21, and D-23s as having their range stretched to a 750 mile radius of action, with about 15 minutes available for combat in the target area.

The comparison between the superior maneuverability and inferior armament and pilot protection of the Japanese fighters along with the P-47’s superior armament, its ability to dive, to survive significant damage, to protect the pilot, and the achieve high speed in level flight dictated the tactics in the arena.

Grosshuesch explained that once the enemy was sighted, he always tried to position himself and his formation above and behind the target aircraft. The P-47s would then make a diving pass on the enemy, firing as they went. Capt. Grosshuesch told his men to maintain speeds up to 200 miles an hour at all times in combat and to never chop the throttle.

“One good burst will finish him anyway. My advice is if you don’t get him on your first pass, pull off to the side and climb at 200 mph. After you have altitude, come back and do it again.”

Grosshuesch also mentioned that he would never refuse a head-on pass, because the P-47’s superior firepower of eight .50 caliber guns “would take care of that”.

And that’s all for this month. We wish to thank AirCorps Aviation, Chuck Cravens for making this report possible! We look forwards to bringing more restoration reports on progress with this rare machine in the coming months. Be safe, and be well

Related Articles

Richard Mallory Allnutt's aviation passion ignited at the 1974 Farnborough Airshow. Raised in 1970s Britain, he was immersed in WWII aviation lore. Moving to Washington DC, he frequented the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum, meeting aviation legends.

After grad school, Richard worked for Lockheed-Martin but stayed devoted to aviation, volunteering at museums and honing his photography skills. In 2013, he became the founding editor of Warbirds News, now Vintage Aviation News. With around 800 articles written, he focuses on supporting grassroots aviation groups.

Richard values the connections made in the aviation community and is proud to help grow Vintage Aviation News.