Inside a former Luftwaffe hangar packed with dozens of historic aircraft, restoration workers at the Flyhistorisk Museum in Sola, Norway are now in the final stretch of rebuilding the world’s last surviving Caproni Ca.310 Libeccio (“southwest wind”), an Italian reconnaissance bomber exported that was one of four exported to Norway shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War. It is remarkable to see the aircraft today, which came to the museum as a rusting framework of welded tubular steel, being returned to its former glory. But what is equally as interesting as its rebirth is the story of how an Italian combat aircraft came to serve Norway.

The Caproni Ca.310 was developed by Caproni’s chief designer, Cesare Pallavicino, to serve as both a twin-engine reconnaissance aircraft/light bomber, and to be a replacement for other designs such as the Ca. 309 Ghibli (Libyan term for ‘desert wind,’ whose name served as an inspiration for the Japanese animation company Studio Ghibli). The Libeccio was of mixed construction, featuring a metal monocoque cockpit section attached to a welded steel tube fuselage frame covered in doped fabric, with wooden bars and panels on its top and bottom. Both the vertical and horizontal stabilizers were made of wood and fabric, while the construction of the wing involved wooden spars and ribs, with metal leading edges inboard of the engine nacelles, plywood leading edges on the outer panels, and doped fabric on the trailing section. The Libeccio’s first flight took place on February 20, 1937, and its two 470 hp Piaggio Stella P.VII 7-cylinder radial engines powered the aircraft to a top speed of 227 mph, with a cruising speed between 177-194 mph.

The Ca.310 was only lightly armed, with two forward-firing 7.7mm Breda SAFAT machine guns in the wing roots, and a single 7.7mm Breda SAFAT in a ventrally mounted turret. When not equipped with two supplemental fuel tanks in the fuselage for long-range flights, the Libeccio could carry up to 450 kg (992 lb) of bombs or serve as a light transport. The Ca.310’s first taste of combat occurred in 1938 during the Spanish Civil War, with 16 of them joining the Italian Legionary Air Force (Aviazione Legionaria) on the side of Francisco Franco’s Nationalist forces. The Ca.310 also enjoyed some export success, with examples being delivered to Hungary, Norway, Yugoslavia, and Peru, where it served in the Ecuadorian Peruvian War of July 1941. Following the Second World War, only one example remains, and this is the example being rebuilt by the Flyhistorisk Museum in Sola.

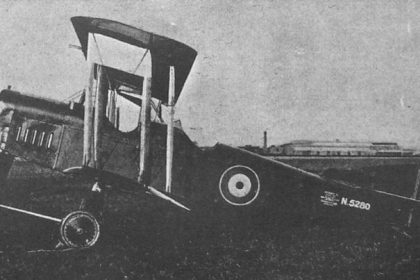

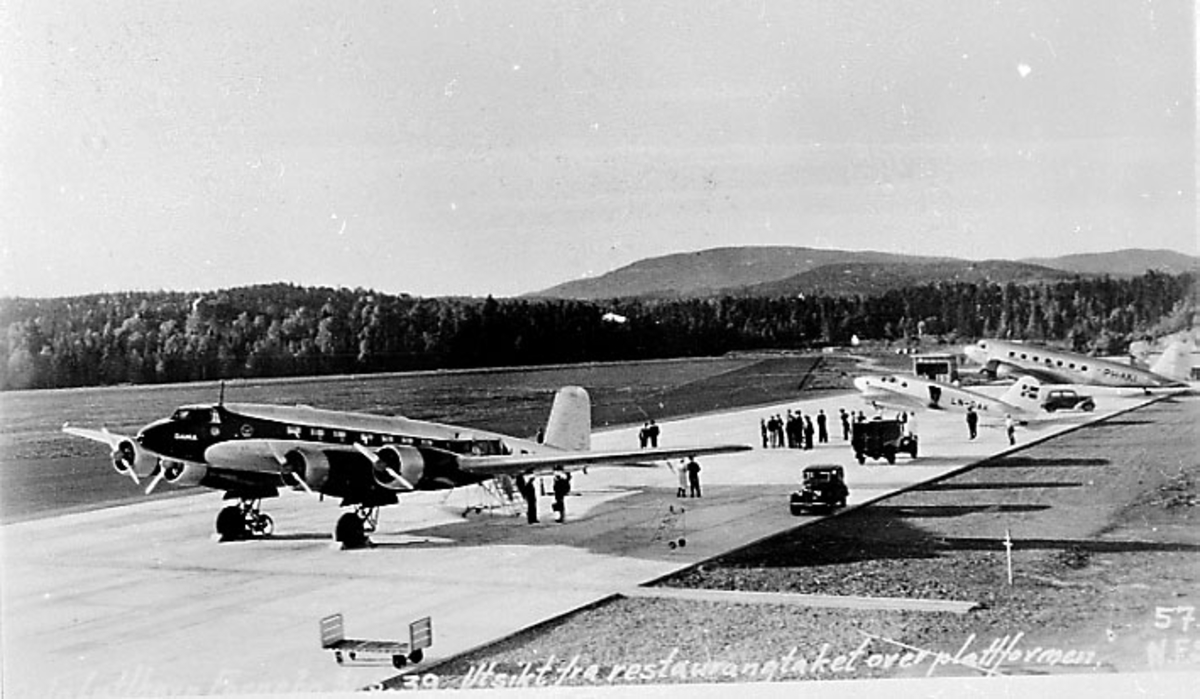

Norway had ordered 24 airframes for its Army Air Service (the Hærens flyvåpen) as part of a trade deal with Italy, which was to receive a supply of dried and salted cod (klippfisk, or “cliff-fish”) in exchange, leading the Norwegians calling the aircraft the “Klippfiskbomberent” (Klippfisk bomber). The first four Ca.310s (LN-501, -503, -505, and -507) for Norway were produced at Caproni’s factory in Milan in October 1938 and handed over to the Norwegian pilots who would fly them north through Germany and Denmark. Once the Cliff-fish bombers arrived in Norway, however, the Norwegian Army Air Service expressed great dissatisfaction with the Ca.310’s performance following the arrival of the first four examples and canceled the balance of the order as a result. In their place, the Norwegians asked for 12 Caproni Ca.312s instead. The Ca.312 (later developed into the Ca.313), was an improvement of the Ca.310 which featured a “stepless” plexiglass cockpit and two 700 hp Piaggio Stella P.XVI RC-35 radial engines. However, the four Ca.310s were modified at the Kjeller Aircraft Factory in Lillestrøm, where the licensed Caproni Ca.312s were to be built. Additionally, Ca.310 LN-503 was temporarily recalled for civilian life as a mailplane with the registration LN-DAK and the name Brevduen (Carrier Pigeon) before it was returned to military service. At the same time Norway ordered the Ca.312 for export and licensed production, Sweden received its order of Ca.313s, while the Norwegian Ca.312s were still awaiting shipment from Italy by the time Germany invaded Norway on April 9, 1940. The invasion of Norway and of neighboring Denmark marked the close of the quiet early phase of WWII known colloquially in Britain as the ‘Phony War’ and to the Germans as the “Sitzkrieg” (Sitting War).

The aircraft in Sola is one of the four original Ca.310s which Norway received in October of 1938 after it was produced by Caproni in Milan as construction number 362. The aircraft was given the fuselage code LN-505 and flown from Italy to Norway by Lt. Odd Bull, who later served the Allies in exile, helping to establish the Little Norway training camp for Norwegian pilots in Toronto, Canada after the fall of Norway in 1940. In the postwar years he would serve as the Chief of Air Staff in the Royal Norwegian Air Force. Bull would later describe the flight in a postwar Norwegian magazine article as a “flight with obstacles.” After only 6 hours of instruction, Bull and his colleagues, most of whom had never flown multi-engine aircraft before, where now entrusted to fly the Capronis from Italy to Norway. The first leg of the journey went smoothly, with stops at Lake Garda, Bolzano, and Innsbruck in recently annexed Austria.

While on their way to a stop in Augsburg, Germany, one of LN-505’s engines began to misfire before quitting altogether. Bull’s inexperience with twin-engine aircraft in general made it difficult for him to maintain control. Luckily, he and his crew had earlier spotted an unmarked airfield and made an approach for it. While they had a radio onboard, none of the three men had experience working it, and flew it straight in for a landing. Before they knew it, a German staff car drove up quickly, and the men were interrogated on the field, which they were later told was a testing field for Messerschmitt’s Bf 109 and Bf 110 fighters, and that the Norwegians had nearby been shot down by the German anti-aircraft gunners! As soon as the Germans learned of their reason for landing, though, they became very accommodating, and a mechanic was called up from the Caproni factory in Milan to restore LN-505’s engine to running order. By the time they were ready to go, however, the mechanic Ensign Larsen had to be hospitalized for severe appendicitis, with Bull and his copilot Hansen agreeing to meet up with Larsen alter and proceed with their flight home.

Later on, they flew past a German naval installation near Hamburg, and after departing from a stop in Copenhagen, LN-505’s fire alarm went off, forcing Bull to land back at Copenhagen. Upon inspection, though, it was found that faulty wiring that had vibrated out of place during the flight, triggering the alarm. Following these repairs, LN-505 arrived safely in Norway. When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, Norway remained neutral, just as the country had done during the First World War, but there was tension in the cold Norwegian air. The four Capronis were assigned to the Bomb Wing at Sola Airfield, near Stavanger, and were kept on neutrality guard, conducting coastal patrols for any ships, British or German, that might violate Norway’s territorial waters. But with Britain and France seeking to stop the neutral trade of iron ore from Norway and Sweden to Germany and Germany seeking to establish bases for the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe, war was all but inevitable for Norway. By 1940, it was only a matter of when the fighting would commence.

When the German invasion commenced on April 9, 1940, the four Ca.310s (codes LN-501, -503, -505, and -507) were still in Sola, along with several Fokker C.V reconnaissance bombers and two De Havilland Tiger Moth trainers/courier aircraft. The bomber wing at Sola had received orders to fly to the airfield at Kjeller, just outside the capital city of Oslo, some 320 kilometers (207 miles) to the northeast, and to bomb a German transport ship in Trysfjorden, near the town of Søgne. But just as three of the Ca.310s were getting ready to depart, six Junkers Ju 88 bombers and two Messerschmitt Bf 110 Zerstörer heavy fighters attacked Sola, dropping bombs and strafing the airfield with machine guns and cannons. LN-507 was hit and partially destroyed, while LN-503, flown by Lt. Niels Steen managed to take off, but one of its engines was disabled during the German air attack. Steen was forced to land near Opstad, some 17 kilometers (11 miles) southeast of Sola, where he and his crew burned LN-503 to prevent its capture. Only LN-505, flown by Halvdan Hansen, commander of both the Bombing Wing and the Sola Air Station, managed to successfully escape from Sola, along with six Fokker C.Vs of the Bomber Wing. With German troops seeking to take the airfield with paratroopers and infantrymen flown in by Junkers Ju 52 transports, Ca.310 LN-505 and the Fokkers flew on to Kristiansand. Meanwhile, Ca.310 LN-501, which had been grounded for maintenance, was captured by the Germans at Sola.

Aboard LN-505, 1st Lt. Hansen would find the German transport in the Trysfjorden, just as had been reported. Being ahead of the older and slower Fokker biplanes, he attacked the transport, but the bombs he was carrying missed the ship, and instead of the geysers of water expected by a bomb blast, the bombs failed to detonate. Unknown to him or his flight crew, however, at least one bomb had failed to leave the bomb bay, but this would not be discovered until later. At 9:30am, LN-505 landed at the nearby airfield in Kjevik, still in Norwegian hands for the time being, for refueling. After this pit stop, the crews of the Caproni and the Fokkers had to move on. By 12:45, they had flown to Steinsfjorden, a frozen lake just outside Oslo. At this early stage in the campaign, both the Allies and the Germans would use frozen lakes as makeshift landing fields. By evening, Hansen received orders to proceed to Brumunddal, and by the following day, they would fly on. But without warning three German aircraft appeared and fired upon the Caproni. Lt. Hansen and flight engineer Hagen returned fire with two machine guns, but as soon as the German had arrived, they had disappeared. The Caproni was only slightly damaged, though, and was soon repaired. However, the Caproni needed to refuel its oil tanks, and with no trucks or storage tanks around, oil was siphoned from a Gloster Gladiator fighter to replenish the Caproni.

Hansen then flew LN-501 to Telemark, then to Møsvatn with around 6 soldiers who joined the flight at Telemark. After two days, though, the Caproni was snowed in, and the men had to work to ready the plane to take off again. Four of the soldiers remained behind to fight, but LN-505 carried on to a frozen lake Brumunddal.

By April 17, the aircraft was flown by Lieutenant Reidar Biong to another frozen lake, Vangsmjøsa (alternatively known as Vangsmjøse), situated in the mountainous Valdres district, and close to the Bombing Wing’s new base of operations near the village of Øye. This was to be the last flight of LN-505, as the crew had increasing difficulties in starting its engines for flight operations. In an attempt to conceal the aircraft, it was towed to the shore, white-washed to blend in with the snow, and lightly covered with branches from nearby trees. The Caproni was then abandoned, with the crews taking off in their Fokker C.Vs. Later on, a few Heinkel He 111s bombed and strafed the aircraft, but LN-505 was still largely intact. Soon, several Germans came to the aircraft but were also unable to restart the Italian engines. On April 20, the Germans stripped LN-505 of any useful parts and set fire to it. The bomb that was still jammed in the bomb bay failed to explode, and when the fire died out, the bomb was taken out of the wreckage and thrown into the thawing lake.

What was left of the Ca.310 was left to the elements on the lake shore, with the wings eventually going into the lake as well. By 1981, the remains of the fuselage were recovered and stored in the garden of a local farm in the village of Grindaheim, on the shores of Vangsmjøsa, while the turret was recovered and sent to the Norwegian Aviation Collection in Bodø. In 1990, with permission from the Armed Forces Museum, the remains of the Caproni’s fuselage were transported to the Flyhistorik Museum in Sola, the very same place from where its exodus to Vangsmjøsa had begun all those years ago. Now, the tubular framework of the fuselage has served as the basis for a reconstruction of the last surviving Caproni Ca.310 in the world.

Rebuilding the Klippfiskbomberent has been no easy task, and the volunteers at Sola had their work cut out for them at the start of the project. But fortunately, the museum was able to make some influential connections. The museum contacted the son of Count Giovanni Caproni, the founder of the Caproni company, and he let the team make copies of the original factory drawings for the Ca.310. Additionally, the Swedish Air Force Museum (Flygvapenmuseum) has a replica of a Caproni Ca.313 (called the S 16 in Swedish service, this replica was built using some original Caproni parts), which was based on the design of the Ca.310, and also had drawings of the aircraft structure for the Norwegian team in Sola to reference for their own project.

Even after the fuselage framework returned to Sola, more parts of the original aircraft would surface. The remains of the Caproni’s wings were discovered by divers on the bottom of Vangsmjøsa, and in 2010, parts of the cockpit and windscreen were found behind a local barn, parts of the nose were believed to have been used as part of a snowmobile, and the turret was in the collections of the Norwegian Aviation Museum (Norsk Luftfartsmuseum) in Bodø. After the fuselage framework was straightened and welded where needed, the frame was transported to Kjevik Airport, where volunteers Tor Holgersen and John Amundsen rebuilt the wooden parts of the aircraft (roof, tail selection, ailerons, flaps, wingtips and the rib sections of the wing’s internal structure, all of which was later returned to Sola.

By 2012, the wing spars were reconstructed inside the museum’s carpentry shop. While the inner panels of the wings, up to the engine nacelles and the 13th row of ribs was reinstalled to the frame of the aircraft, lack of spacing inside the museum’s WWII-era exhibition hangar among the other aircraft constricted the museum from reinstalling the outer wing panels for several years. However, with the reorganization of the layout of the museum’s hangar, the outer wing panels, flaps and ailerons, which were finished in the museum’s restoration workshop, were finally fitted back onto the Caproni, which was also moved to another spot in the hangar as part of the new aircraft layout. The metal-skinned nose section of the aircraft was also reproduced using remains from the original found near Vangsmjøsa as a guide, along with a wooden mockup of the framework used for reference for the new metal nose. This new nose section was constructed by volunteers Roar Henriksem, Siegfried Hernes and Harald Egge, and has been refitted to the fuselage, whose fabric had been doped, along with the fabric on the wing and tail surfaces.

Finding two Piaggio P.VII radial engines anywhere in the world, let alone in Norway, is exceedingly rare today, so the museum elected to build a set of replicas for the engines. Reference material in the form of technical drawings of the engines in the Norwegian Aviation Collection and in data concerning preserved P.VII engines such as the one in the Museo del Aire in Madrid, Spain was compiled, but there was still a lack of information. At least one P.VII cylinder was found and incorporated into the build of the replica engines, which came to be of mixed construction, with assemblies being reproduced from aluminum, plywood, fiberglass, and 3D printing materials. Similarly, the museum was able to find one of the two Piaggio-built propellers from LN-501, but due to concerns of weight in the replica engines, it was designed to make fiberglass replicas of the propellers as well, based on molds of the original propeller. The museum’s restoration also lacked the resources to shape metal for the aircraft’s engine cowlings, so it was chosen to replicate these with fiberglass as well. Though these changes of course mean that the aircraft will remain static, it will remain accurate in proportions to the original materials.

The landing gear of the Libeccio was typical of many early war taildraggers, with a retractable main undercarriage that tucked partially into the engine nacelles and a fixed tailwheel. While the tail wheel was reproduced through local sources, the main landing gear wheels were acquired from Sweden with some help of the Swedish Air Force Museum, as the landing gear of the Ca.313 was similar to that on the Ca.310. The landing gear legs for the Ca.310 were also similar to those on the Ca.313, so in addition to using the Swedish Air Force Museum’s Ca.313 as a reference guide, drawings were copied for the Norwegian Caproni project.

By 2024, the aircraft was at last coming together, with the nose section being installed on the fuselage frame, the wings at their full span, and paintwork began on the aircraft. The rudder and wingtips have been painted with the Norwegian insignia of the period, and the woodland camouflage pattern applied by the Italians in Milan has been replicated. Today, the newly repainted Caproni rests on a cradle, but will soon rest on its landing gear and stand proudly among the Flyhistorisk Museum’s collections to serve as a tribute to the sacrifices of Norwegian airmen in defending their homeland from 1940 onwards and preserves a unique example of pre-war Italian military aviation.

To learn more about the Flyhistorisk Museum Sola, visit their website as well as the website for the Venneforeningen Flyhistorisk Museum Sola (Aviation History Museum Sola Association). Special thanks to Ernst Knuton and Kjell Dahle for their help in compiling the history of the Caproni Ca.310 LN-505, their role in restoring the aircraft, and in providing photographs of the restoration. You can see Knutson’s photos here: Caproni Ca.310 Sn.505 | Flickr, and Dahle’s blog on the Caproni here: Caproni Ca.310.