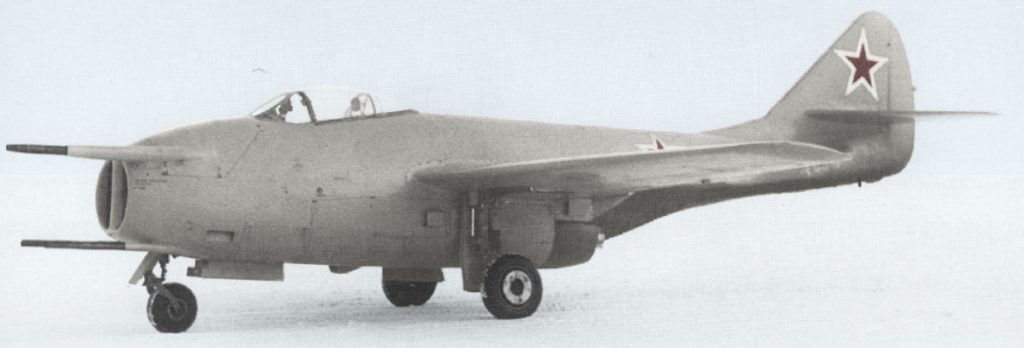

The development of the MiG-15 began with the first jet built by the Mikoyan-Gurevich Design Bureau, the MiG-9 (NATO reporting name: Fargo). The MiG-9 was powered by a pair of reverse-engineered BMW 003 turbojet engines. However, the MiG-9 suffered from a range of issues relating to power output to engine flameouts when gases from the nose-mounted guns being ingested into the engines. Soviet jet development prior to the Second World War, like much of the Soviet aviation industry, was under the constant strain of engineers being caught up in Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin’s purges, and with the German engines captured at the end of WWII having been built using inferior alloys and often with slave laborers who sabotaged the internal mechanisms of the engines, the Soviets knew that they would need to catch up rapidly to the Western powers, who were now locked in a Cold War with the Soviets.

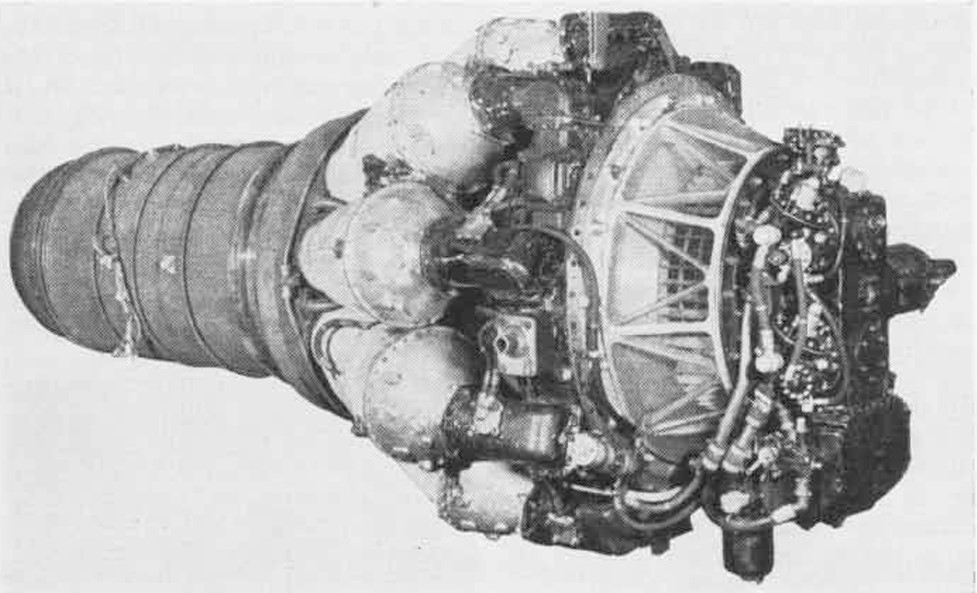

One fact that was inescapable to the Soviet engineers, however, was that the British were now at the forefront of jet technology, with companies such as Rolls-Royce and De Havilland building new, more powerful engines for their growing line of jet fighters and had licensed the design of these engines to the Americans for their own fighters. If the Soviets were somehow able to obtain a number of the latest British jet engines, they could design fighters that were a match to the British and American designs, and which would be able to intercept the high-flying B-29 Superfortresses, which were now capable of carrying atomic weapons, which the US was enjoying a brief monopoly on. But this was easier said than done. When the Soviet Minister of Aviation Industry Mikhail Krunichev and designer Alexander Yakovlev proposed purchasing examples of the new Rolls-Royce Nene engine, Stalin is reported to have said, “What fool will sell us his secrets?” As it turned out, the new Labour government in Britain under Clement Atlee was seeking to improve postwar relations between the UK and the USSR to maintain the peace in Europe. Soon, aircraft designer Artem Mikoyan, engine designer Vladimir Yakovlevich Klimov, and others travelled to the UK under Stalin’s blessing to request access to the Nene engines. Incredibly, the British Minister of Trade, Sir Stafford Cripps, who was also the former Minister of Aircraft Production, granted a production license for the Nene, along with complete blueprints and a few engines selected for transport to the Soviet Union. Now that the Nene, one of the world’s most advanced jet engines of the time, which was produced in the USSR as the Klimov RD-45 (later designated as the VK-1), was in Soviet hands, it was up to Mikoyan-Gurevich to build a plane around the engine.

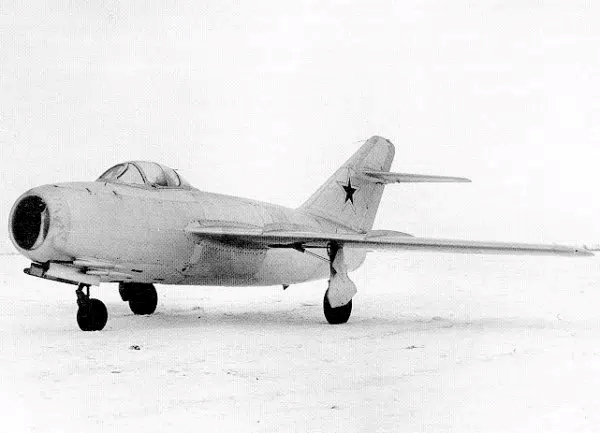

The result was the prototype jet interceptor originally called the I-310. The design featured a 35-degree swept wing, with two sets of wing fences on each wing. The horizontal stabilizer was attached to the vertical stabilizer, and the aircraft was fitted with a 37mm Nudelman N-37 autocannon and two 23mm Nudelman-Rikhter NR-23 autocannons, which gave the fighter enough firepower to destroy an American B-29. On December 30, 1947, test pilot Viktor Nikolaevich Yuganov opened up the throttle and lifted off in the first I-310, serial number S01. A year and one day later, on December 31, 1948, the first production model MiG-15 took to the air, and by 1949, the first production aircraft began entering service with the Soviet Air Forces. In the West, the MiG-15 received the NATO reporting name “Fagot”; its meaning derived from a wooden bundle.

While the MiG-15 would become inextricably linked with the air war over Korea, the first time the MiG-15 was deployed in a combat environment was in the skies above China. Although the Chinese Communists under Mao Zedong had seized control over mainland China and declared the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the opposing Nationalists from the Republic of China (ROC) reformed themselves on the island of Taiwan and continued aerial incursions into mainland China against cities such as Shanghai, prompting the Soviets to send a division of MiG-15s and Soviet pilots to China in February 1950 to oblige Mao’s requests for support. It is reported that on April 28, 1950, the MiG-15 scored its first air-to-air victory against a ROCAF reconnaissance variant of a P-38 Lightning (an F-5).

When North Korea invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950, starting the Korean War, the Korean People’s Air Force (KPAF) was equipped with WWII era Soviet aircraft such as Yakovlev Yak-9 fighters and Ilyushin Il-10 attack aircraft. When the US-led UN forces came to the aid of South Korea, the American-led air forces gained air superiority over the Korean Peninsula, with many of their pilots being more experienced and better trained than the North Korean pilots. Indeed, the amphibious landings at Inchon and the arrival of reinforcements pushing up from Pusan led not only to the fall of Pyongyang, but also saw the North Koreans pushed close to the Chinese border. This ensured that China became an active participant in November 1950, and the Soviet Union became a barely disguised ally as well. Open involvement by the Soviets, who had tested their own atomic bomb just one year prior, threatened to escalate the war beyond Korea. As such, the Soviets gave supplies to China and North Korea, and trained Chinese and North Korean pilots how to fly the MiG-15. What the Soviets did not make public was the fact that numerous Soviet airmen not only provided local instruction but also participated in aerial combat against the Americans and British Commonwealth forces. It was also around this time that the MiG-15bis (second) model was introduced to be ever more combat capable.

At first, the MiG-15 proved to be more than a match against the UN jet fighters such as the Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star, Republic F-84 Thunderjet, Grumman F9F Panther, and Gloster Meteor, but the Americans soon responded with their own swept wing fighter, the North American F-86 Sabre. While the MiG was more heavily armed and was lighter than the Sabre, the Sabre had an all-moving tail that allowed for better controllability at transonic speeds and a radar gunsight that offered more accurate fire at longer ranges than the manual gunsight on the MiG. As the war on the ground became a stalemate, Sabres and MiGs battled above the Yalu River along the North Korean/Chinese border in what American pilots called “MIG Alley”. However, the MiG-15s flown by Soviet, Chinese, and North Korean pilots would exact a heavy toll against UN air forces, with B-29 Superfortresses turning to night bombing in October 1951 in the face of mounting losses, and American fighter aces calling the more experienced of their adversaries “Honchos”, which were often Soviet WWII aces, such as Colonel Ivan Kozhedub, commander of the 324th Fighter Aviation Division, and the highest scoring Allied fighter pilot of WWII. On July 27, 1953, an armistice was signed that ended all fighting on the Korean Peninsula, which after three years of back-and-forth warfare, would remain divided, as it is to this day.

Though much was learned through the accounts of the Sabre pilots who flew against the MiG-15s, the Americans were eager to get their hands on a working, intact example for study and evaluation. In order to entice communist pilots wishing to defect, the Americans commenced with Operation Moolah, offering a $100,000 reward ($1,309,099.59 in 2024) and political asylum. On September 21, 1953, a disillusioned North Korean pilot named No Kum-Sok took off from Pyongyang on a routine patrol in his MiG-15 and landed at Kimpo Air Base (now Gimpo International Airport) in Seoul, South Korea. Ironically, Sok was unaware of the reward, and choose to defect on his own initiative. He later moved to America, changed his name to Kenneth Rowe, and became a successful aerospace engineer. The MiG he flew to Kimpo was later flight tested by USAF test pilots, including Chuck Yeager before going on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

By the time the Korean War came to an end, the MiG-15 had led to the development of the MiG-17 (NATO reporting name “Fresco”), but the MiG-15 would be exported around the Communist world, not only as a single-seat fighter but also as a two-seat training model, the MiG-15 UTI. The aircraft was also manufactured under license in Czechoslovakia as the S-102 (training version CS-102), in mainland China as the J-2 fighter and JJ-2 trainer, and in Poland as the Lim-1 (MiG-15), Lim-2 (MiG-15bis), and the SB Lim-1 and SB Lim-2 trainer models. Besides their combat action over Korea, MiG-15s were involved in shooting down NATO military aircraft operating near or violating the airspaces of communist states. They were also flown by Egyptian pilots against British, French, and Israeli pilots during the Suez Canal Crisis of 1956. In 1958, MiG-15s and J-2s of the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) engaged Taiwanese F-86 Sabres flown by the Republic of China Air Force (ROCAF) during the Taiwan Strait Crises. In 1958, ROCAF Sabres scored the first kills for the AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missile against the PLAAF MiG-15s/J-2s.

Today, several examples of the MiG-15 survive around the world today. After the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, many Polish and Czechoslovakian-built MiG-15s, along with some surplus models acquired through trade with China, were acquired by Western collectors, primarily in the United States, and a number of these were even made airworthy, with the majority having been painted in North Korean markings to represent aircraft flown against USAF F-86 Sabres during the Korean War. Incredibly, a few examples remain in active duty in North Korea as training aircraft, being among the oldest military aircraft still in service today.

Long after the type’s first flight, the MiG-15 remains a fixture in discussions about the Korean War. Those who flew and maintained it found it to be a rugged aircraft, and it would forge a linage of Soviet and Russian fighter jets that remain in service to this day.

Today in Aviation History is a series highlighting the achievements, innovations, and milestones that have shaped the skies. All the previous anniversaries are available HERE